Buscarello de Ghizolfi, also known as Buscarel of Gisolfe, was a European who settled in Persia in the 13th century while it was part of the Mongol Ilkhanate. He was a Mongol ambassador to Europe from 1289 to 1305, serving the Mongol rulers Arghun, Ghazan and then Oljeitu. The goal of the communications was to form a Franco-Mongol alliance between the Mongols and the Europeans against the Muslims, but despite many back-and-forth communications, the attempts were never successful.

Biography

editLittle is known of Buscarello except for his work as an ambassador, and that he was a member of the powerful Ghisolfi family. The first mention of him is in 1274, in relation to the arming of a galley. The next is from 1279, which records that he was in the city of Ayas in Cilician Armenia, at the time a vassal state of the Mongol Empire. He then entered the service of the Mongol ruler Arghun, becoming Officer of his guard, with the title of Qortchi ("Quiver carrier").[1][2]

Buscarello had a son, Argone de Ghizolfi, whom he named "Arghun" after his patron.[1][3]

Ambassador

editIn 1289, Arghun sent a mission to Europe, with Buscarel as ambassador. Other adventurers, such as Tommaso Ugi di Siena and Isol the Pisan, are known to have played similar roles at the Mongol court, as hundreds of Western adventurers entered into the service of Mongol rulers.[4] Buscarel's journey was the third attempt by Arghun to form an alliance with the Europeans.

Buscarel was in Rome between 15 July and 30 September 1289, and in Paris in November–December 1289.[5] Via Buscarel, Arghun informed the European nobles, such as King Philip IV of France and Edward I of England, that Arghun would march his troops as soon as the Crusaders had disembarked at Saint-Jean-d'Acre, and that the Mongols would deliver between 20,000 and 30,000 horses and all needed supplies to the Crusaders if they would come to the Holy Land. Arghun also promised that he would deliver Jerusalem to the Europeans if Egypt was successfully conquered:[6][7]

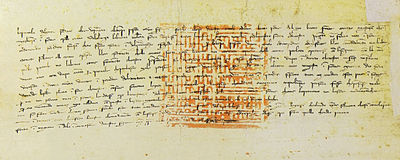

French National Archives.

Under the power of the eternal sky, the message of the great king, Arghun, to the king of France..., said: I have accepted the word that you forwarded by the messengers under Saymer Sagura (Bar Sauma), saying that if the warriors of Il Khaan invade Egypt you would support them. We would also lend our support by going there at the end of the Tiger year's winter [1290], worshipping the sky, and settle in Damascus in the early spring [1291].

If you send your warriors as promised and conquer Egypt, worshipping the sky, then I shall give you Jerusalem. If any of our warriors arrive later than arranged, all will be futile and no one will benefit. If you care to please give me your impressions, and I would also be very willing to accept any samples of French opulence that you care to burden your messengers with.

I send this to you by Myckeril and say: All will be known by the power of the sky and the greatness of kings. This letter was scribed on the sixth of the early summer in the year of the Ox at Ho’ndlon."

— Letter from Arghun to Philippe le Bel. Dated 11 May 1289. France royal archives[8]

Buscarello also remitted to Philip a memorandum in French describing the details of the proposed combined action:

First of all, Arghun informs the King of France as a brother that, in all parts of the Orient among the Tartars, the Saracens and any other people, the greatness, power and faithfulness of the Kingdom of France has a certain renown, as well as the King of France, his Barons and his powerful Knights, who came several times to the help and the conquest of the Holy Land, in the honor of the son of the Virgin Mary and of all the Christian people. And the said Arghun informs the King of France as his brother that he himself and his army are ready and equipped to go to the conquest of the Holy Land and to be together with the King of France in this rightful service.

And I, Buscarel, in respect to this message from Arghun, say that if you, King of France, come in person to accomplish this rightful service, Arghun will bring with him two Christian Georgian kings under his lordship, who will be able to bring with them more than 20,000 horsemen.

I also say that, since Arghun has heard that it was very difficult for the King of France and his Barons to bring with them across the sea all the horses needed for their knights and their men, the King of France will receive from Arghun 20,000 to 30,000 horses as a gift.

Similarly, if you, King of France, so desires, Arghun will have all Turkey (Seljoukid Anatolia) prepare for you and for this rightful service animal meats, oxen, cows and camels, grains and flour, and any other available food according to your wish and request.

— Memorandum from Buscarel to Philippe le Bel.[9]

Buscarel then travelled to England to bring Arghun's message to Edward I, arriving in London on 5 January 1290. Edward answered enthusiastically to the project, but deferred the decision about the date to the Pope, failing to make a clear commitment.[10]

After his meeting with Edward, Buscarello returned to Persia, accompanied by the English envoy Sir Geoffrey de Langley.[1]

Buscarel made multiple other trips back and forth between the Ilkhanate and Europe, acting as an ambassador for various Mongol rulers in turn. He represented Ghazan in 1303, carrying a message which reiterated Hulagu's promise that the Mongols would give Jerusalem to the Franks in exchange for help against the Muslim Mamluks.[1] In 1303, the Mongols did attempt to invade Syria in great strength (about 80,000 troops), but were defeated at Homs on 30 March 1303, and at the decisive Battle of Shaqhab, south of Damascus, on 21 April 1303.[11] It is considered to be the last major Mongol invasion of Syria.[12]

1305 embassy

editIn April 1305, Ghazan's successor Oljeitu sent letters to King Philip IV of France,[13] the Pope, and Edward I of England, again through an embassy by Buscarel, who himself wrote a translation of Oljeitu's letter. The message explained that internal conflicts between the Mongols were over, and promised the delivery of 100,000 horses to the Crusaders upon their arrival in the Holy Land.[6] Also, as had the previous Ilkhanate rulers, Oljeitu offered a military collaboration between the Christian nations of Europe and the Mongols against the Mamluks, but again, the attempts at forming an alliance were unsuccessful.

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d Jean Richard (1990) “Buscarello de Ghizolfi.” Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 6, pg. 569.

- ^ Jean-Paul Roux, p.410

- ^ C. Desimoni, I conti dell’ambasciata al chan di Persia nel 1292 in Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria Vol. 13, 1877-84, pp. 539-590.

- ^ Roux, p.410

- ^ Grousset, p.711

- ^ a b Peter Jackson, p.178

- ^ Jean Richard, p.468

- ^ Source Archived August 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quoted in Grousset, p.712

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades III", René Grousset, p.713.

- ^ Demurger, p. 158

- ^ Nicolle, p. 80

- ^ Mostaert and Cleaves, pp. 56-57, Source Archived 2008-04-04 at the Wayback Machine

References

edit- Demurger, Alain (2007). Jacques de Molay (in French). Editions Payot&Rivages. ISBN 978-2-228-90235-9.

- Grousset, René (1935). Histoire des Croisades III, 1188-1291 (in French). Editions Perrin. ISBN 2-262-02569-X.

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-36896-5.

- Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071-c. 1291. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62566-1.

- Roux, Jean-Paul (1993). Histoire de l'Empire Mongol (in French). Fayard. ISBN 2-213-03164-9.