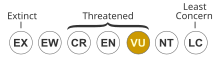

The broad stingray (Bathytoshia lata), also known as the brown stingray or Hawaiian stingray, is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae. They range across the Indo-Pacific from southern Africa to Hawaii, and are the predominant species of stingray in the inshore waters of the Hawaiian Islands. This benthic fish also inhabits sandy or muddy flats at depths greater than 15 m (49 ft) in the Eastern Atlantic, from southern France to Angola, including the Mediterranean Sea. Usually growing to 1 m (3 ft) across, the broad stingray has a wide, diamond-shaped pectoral fin disc with a protruding snout tip and a long tail with a ventral fin fold. At night, this species actively forages for bottom-dwelling invertebrates and bony fishes, often near the boundaries of reefs. Reproduction is aplacental viviparous. As substantial threats to its population exist in many areas of its wide distribution, IUCN has listed this species as Vulnerable.

| Broad stingray | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Myliobatiformes |

| Family: | Dasyatidae |

| Subfamily: | Dasyatinae |

| Genus: | Bathytoshia |

| Species: | B. lata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bathytoshia lata (Garman, 1880)

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Taxonomy and phylogeny

editAmerican zoologist Samuel Garman described the broad stingray in an 1880 issue of the scientific journal Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, giving it the name Trygon lata from the Latin word for "broad".[3][4] Subsequent authors synonymized Trygon with Dasyatis.[5] The type specimen was collected from what were then called the "Sandwich Islands", and measures 52 cm (20 in) across.[3]

Lisa Rosenberger's 2001 phylogenetic analysis of 14 Dasyatis species, based on morphological characters, found that the sister species of the broad stingray is the roughtail stingray (B. centroura), and that they form a clade with the southern stingray (Hypanus americanus) and the longtail stingray (H. longus). As B. centroura is found in the Atlantic, this suggests that it and B. lata evolutionarily diverged before or with the formation of the Isthmus of Panama (about 3 million years ago).[6] A further review based on Molecular phylogenetic data in 2016 added Dasyatis thetidis, Dasyatis ushiei, and eastern Atlantic B. centroura as populations of this species.[7]

Distribution and habitat

editBathytoshia lata occurs in the eastern Atlantic and the Indo-Pacific from southern Africa to the Hawaiian Islands [8] and is also found in the Mediterranean Sea [9] with occasional records from Spain to Turkey.

This species is common in coastal bays with mud or silt bottoms, and may also be encountered in sandy areas or near coral reefs. It is most common at depths between 40–200 m (130–660 ft) but is found as far down as 800 m (2,600 ft).[8]

Description

editThe broad stingray has a diamond-shaped pectoral fin disc a fourth wider than long, with nearly straight leading margins that converge at an obtuse angle, and curved trailing margins. The tip of the snout is rounded and protrudes past the disc. The mouth is arched and contains five or six papillae on the floor, two of which are in front of the others. The pelvic fins are short and rounded. The whip-like tail is twice or more the length of the disc, and bears a serrated stinging spine on the upper surface near the tail base. A long, narrow fin fold occurs beneath the tail, which eventually becomes a keel that runs all the way to the tail tip.[3][4]

Larger rays have three large, elongated tubercles in the middle of the back; the tail is roughened by small dermal denticles, along with an irregular row of conical tubercles on each side and several large, flattened tubercles in front of the spine. This species is plain olive to brown above and white below.[3] Though rarely found so far west, the similar-looking diamond stingray (Hypanus dipterurus) is the only other nearshore stingray that occurs off Hawaii; it can be distinguished from this species by its tail, which is shorter and has both upper and lower fin folds. The broad stingray can reach 1.5 m (5 ft) across and 56 kg (123 lb) in weight, though few exceed 1 m (3 ft) across.[4][10]

Biology and ecology

editDuring the day, the broad stingray is relatively inactive and spends much time lying half-buried on the bottom. A tracking study in Kaneohe Bay found that individuals rays roamed over an average area of 0.83 km2 (0.32 sq mi) at night, compared to an average diurnal activity space of 0.12 km2 (0.046 sq mi), and did not rest consistently in any particular spot. Rays were most active 2 hours after sunset and before sunrise, and were more active in the higher water temperatures of summer than winter. The behavior of this species was not significantly influenced by tides, likely because they inhabit deeper water.[11]

The broad stingray feeds mainly on bottom-dwelling crustaceans, while also taking polychaete worms and small bony fishes.[10] It excavates large pits to uncover buried prey, and is often followed by opportunists such as jacks.[4] Foraging rays favor areas close to reef boundaries, where many parrotfish, wrasses, gobies, and other reef fishes shelter at night.[11] Known parasites of this species include the tapeworms Acanthobothrium chengi, Rhinebothrium hawaiiensis,[12] Pterobothrium hawaiiensis, Prochristianella micracantha, and Parachristianella monomegacantha.[13]

Like other stingrays, the broad stingray is aplacental viviparous.[8] Kaneohe Bay appears to be a nursery area for this species, where juvenile scalloped hammerheads (Sphyrna lewini) and it are the dominant predators.[11] Off North Africa, birthing occurs in June and December, indicating either that females bear two litters per year with a four-month gestation period, or that there are two cohorts of females bearing one litter per year with a ten-month gestation period.[14][15]

Human interactions

editThe International Union for the Conservation of Nature formerly assessed the broad stingray as Least Concern,[16] but this was upgraded to Vulnerable in 2021 as it is not known what part of its range overlaps with marine protected areas.[1] This species has become a popular subject for display at public aquariums and resorts.[4]

References

edit- ^ a b Jabado, R.W.; Chartrain, E.; De Bruyne, G.; Derrick, D.; Dia, M.; Diop, M.; Doherty, P.; Finucci, B.; Leurs, G.H.L.; Metcalfe, K.; Pires, J.D.; Seidu, I.; Soares, A.-L.; Tamo, A.; VanderWright, W.J. & Williams, A.B. (2021). "Bathytoshia lata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T104071039A104072486. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T104071039A104072486.en. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ Bailly, Nicolas (2020). "Bathytoshia lata (Garman, 1880)". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d Garman, S. (October 1880). "New species of selachians in the museum collection". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 6 (11): 167–172.

- ^ a b c d e Hoover, J.P. Fish of the Month: Stingray Dasyatis lata. hawaiisfishes.com. Retrieved on December 5, 2009.

- ^ Catalog of Fishes (Online Version) Archived May 3, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved on December 2, 2009.

- ^ Rosenberger, L.J.; Schaefer, S. A. (August 6, 2001). "Phylogenetic Relationships within the Stingray Genus Dasyatis (Chondrichthyes: Dasyatidae)". Copeia. 2001 (3): 615–627. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2001)001[0615:PRWTSG]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85657403.

- ^ Last, P.R.; Naylor, G.J.; Manjaji-Matsumoto, B.M. (2016). "A revised classification of the family Dasyatidae (Chondrichthyes: Myliobatiformes) based on new morphological and molecular insights". Zootaxa. 4139 (3): 345–368. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4139.3.2. PMID 27470808.

- ^ a b c Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Bathytoshia lata". FishBase. June 2022 version.

- ^ Guide of Mediterranean Skates and Rays (Bathytoshia lata). Oct. 2022. Mendez L., Bacquet A. and F. Briand.http://www.ciesm.org/Guide/skatesandrays/Bathytoshia-lata

- ^ a b Dale, J. (2008). Life-History and Ecology of the Brown Stingray Archived February 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. HIMB Shark Lab. Retrieved on December 5, 2009.

- ^ a b c Cartamil, D.P; J.J. Vaudo; C.G. Lowe; B.M. Wetherbee; K.N. Holland (May 2003). "Diel movement patterns of the Hawaiian stingray, Dasyatis lata: implications for ecological interactions between sympatric elasmobranch species". Marine Biology. 142 (5): 841–847. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1014-y. S2CID 12785003.

- ^ Cornford, E.M. (December 1974). "Two Tetraphyllidean Cestodes from Hawaiian Stingrays". The Journal of Parasitology. 60 (6): 942–948. doi:10.2307/3278520. JSTOR 3278520. PMID 4436766.

- ^ Carvajal, J.; R.A. Campbell; E.M. Cornford (February 1976). "Some Trypanorhynch Cestodes from Hawaiian Fishes, with Descriptions of Four New Species". The Journal of Parasitology. 62 (1): 70–77. doi:10.2307/3279044. JSTOR 3279044. PMID 1255387.

- ^ Struhsaker, P. (April 1969). "Observations on the Biology and Distribution of the Thorny Stingray, Dasyatis centroura (Pisces: Dasyatidae)". Bulletin of Marine Science. 19 (2): 456–481.

- ^ Capapé, C. (1993). "New data on the reproductive biology of the thorny stingray, Dasyatis centroura (Pisces: Dasyatidae) from off the Tunisian coasts". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 38 (1–3): 73–80. doi:10.1007/BF00842905. S2CID 19670885.

- ^ Ebert, D.A.; Vidthayanon, D.A.; Samiengo, B. (2016). "Bathytoshia lata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T161386A104066775. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T161386A104066775.en. Retrieved 10 June 2023.