Robert Charles Wright (born April 23, 1943) is an American lawyer, businessman, lobbyist, and author. He is a former NBC executive, having served as president and CEO from 1986 to 2001, and chairman and CEO from 2001[6] until he retired in 2007.[7] He has been credited with overseeing the broadcast network's expansion into a media conglomerate and leading the company to record earnings in the 1990s.[8] Prior to NBC, he held several posts at General Electric in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. He served as President and CEO of GE Capital, GE Financial Services 1983 to 1986 and served as GE's vice chairman until he retired from that role in 2008.[9]

Bob Wright | |

|---|---|

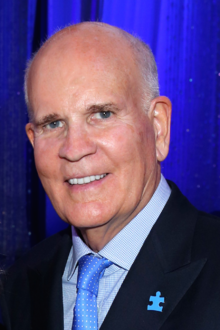

Wright in 2015 | |

| Born | April 23, 1943 Hempstead, New York, U.S. |

| Alma mater | College of the Holy Cross (BA) University of Virginia (LLB) |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for |

|

| Board member of | Polo Ralph Lauren[1] AMC Networks[2] New York-Presbyterian Hospital (life trustee)[3] Palm Beach Civic Association (Chairman and CEO)[4] |

| Spouses | Suzanne Wright

(m. 1967; died 2016)Susan Keenan Wright (m. 2017) |

| Children | 3[5] |

In 2005, Wright and his wife, Suzanne Wright, founded Autism Speaks.[10] In 2016, after his wife's death from pancreatic cancer, Wright established the Suzanne Wright Foundation, which funds research for pancreatic cancer.[11] Through the Suzanne Wright Foundation, he led the initiative to establish a Health Advanced Research Projects Agency, or HARPA, a government research agency modeled after the U.S. Department of Defense's DARPA.[12] On March 15, 2022, Public Law 117-103 was enacted authorizing the establishment of ARPA-H within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.[13]

Early life and education

editWright was born on April 23, 1943, in Hempstead, New York, on Long Island,[5] the only child of Catherine Drum Wright and Gerald Franklin Wright.[14] After graduating from Chaminade High School in Mineola, New York, Wright enrolled at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts.[5] He originally studied pre-med, but later changed his studies to major in psychology and minor in history.[5] He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1965.[5] Wright earned an LL.B. from the University of Virginia School of Law in 1968.[15]

Career

editEarly career

editWright began his career with General Electric as a staff lawyer in 1969.[16] The following year, he left GE to take a judicial clerkship for a federal judge in New Jersey.[9][17] Wright joined GE again in 1973 as a lawyer for the company's plastics unit, where he later took on several management positions.[9] GE made a deal to acquire radio, broadcast TV and cable properties[18][19] of Atlanta, Georgia-based Cox Communications in 1979[20] and appointed Wright as Cox Cable president[17] and executive vice president of Cox Broadcasting.[21] The deal did not come to fruition, however Wright remained with Cox Cable as president until 1983.[17][21] Under Wright's leadership, Cox Cable launched franchises across the U.S., including franchises in Omaha, Nebraska, Tucson, Arizona, New Orleans, Louisiana, Vancouver, Washington, suburbs near Chicago, Illinois, and Providence, Rhode Island, and a portion of Long Island, New York.[22] Wright was a contemporary of Ted Turner (Turner Broadcasting Systems), John Malone (TCI), Chuck Dolan (Cablevision Systems) and Ralph J. Roberts (Comcast) during the early days of cable television.[23] Wright left Cox to join GE once again in 1983, when GE chairman and CEO Jack Welch hired him to lead the company's housewares and audio units.[17] He was promoted to president of GE Financial Services[24][21] from 1984 to 1986.[9]

NBC and NBC Universal

editGE named Wright the president and CEO of the National Broadcasting Company when the company acquired the broadcast network in 1986.[6][25] He succeeded Grant Tinker in the role.[17] He became chairman and CEO of NBC in 2001.[6] He was named chairman and CEO of NBC Universal in 2004.[6]

Upon succeeding Tinker, Wright's main mission became finding new areas of business in addition to running a television network,[26] and transformed the network into a media conglomerate.[27] NBC launched CNBC in 1989 and MSNBC in 1996.[28] Both are examples of the strategic partnerships NBC created under Wright to improve distribution and content.[29] CNBC included a partnership with Dow Jones allowing delivery of local business and financial news in Europe and Asia; and MSNBC was a venture with Microsoft that launched a new 24-hour news network and accompanying news website to combine the two mediums.[24][30][31]

Wright is credited with leading NBC during a time when the company became a powerful media leader, driving the company to record earnings in the 1990s.[8] The network reported $5 billion in revenues and nearly more $1 billion in operating profits in 1996.[8] Also under Wright, NBC acquired Universal Pictures, Telemundo[28] and Bravo.[32]

In the early- and mid-90s, Wright and NBC led efforts to persuade lawmakers and regulators to relax rules preventing networks from becoming multichannel program providers,[33] obtaining certain financial interests and syndication.[34]

General Electric named Wright as vice chairman of NBC's then-parent company in 2000.[16]

Under Wright, NBC completed its acquisition of Vivendi Universal Entertainment in 2004.[35] Led by Wright, the newly formed NBCUniversal controlled seven cable networks, including USA Network and Sci-Fi Channel); 29 TV stations; film and TV studios; and theme parks.[35]

During his career with NBC, Wright was active in opposing digital piracy, and was a founding member of the Global Leadership Group for the Business Alliance to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy. In that role, Wright spoke at the Global Congress on Combating Counterfeiting and Piracy in Geneva, Switzerland, pushing for lawmakers and businesses to curb rising intellectual property theft in the digital age,[36] and delivered a speech titled "Technology and the Rule of Law in the Digital Age" at the Media Institute in 2004.[37] He also penned an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal titled "Stop IP theft".[38] Wright's speech at the Media Institute was published in the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy.[39] His 2002 speech for the Legatus Tri-State Chapter on issues of faith and business was reprinted in 50 High-Impact Speeches and Remarks.[40]

Wright retired from NBC in 2007.[7] When Wright first took the helm at the network, it saw operating profits of $400 million.[17] In 2007, when he retired, NBC generated $3.1 billion in profit on $15.4 billion in revenue.[41] He remained vice chairman of GE until his retirement from that role in 2008.[42]

Autism Speaks

editOne of Wright's grandchildren, Christian, was diagnosed with autism, prompting him and his wife, Suzanne, to found an advocacy group.[10] The couple launched Autism Speaks in 2005, and Wright became its chairman.[10] The Wrights' organization merged with Autism Coalition for Research and Education in 2005, National Alliance for Autism Research in 2006 and Cure Autism Now in 2007.[43][44] In its first 9 years, Autism Speaks invested a half-billion dollars, focusing on science and research.[10] The organization helped persuade the U.S. government to invest billions in autism research;[7] as of 2014, Congress had dedicated more than $3 billion for autism research and monitoring.[10] During Wright's tenure, the organization teamed up with Google in 2014 on the MSSNG project to sequence a database of autism genomes.[45][46] Wright resigned as chairman of Autism Speaks in May 2015; as of February 2016, he remained on the board as a co-founder of the organization and on its executive committee.[47][48] His book, The Wright Stuff: from NBC to Autism Speaks, written with Diane Mermigas, was published March 29, 2016.

The Suzanne Wright Foundation

editBob Wright is Founder and Chairman of the Suzanne Wright Foundation, established in honor of his late wife, Suzanne, who died from pancreatic cancer on July 29, 2016.[49] The Suzanne Wright Foundation launched CodePurple, a national awareness and advocacy campaign to fight pancreatic cancer.[50] Pancreatic cancer has the highest mortality rate of all major cancers. With no screening tools,[51] the mortality rate is 92% and has seen virtually no improvement in more than 40 years.[52] Through advocacy and awareness, the foundation's goal was to accelerate discovery of detection tools, better treatments, and ultimately, a cure for pancreatic cancer.

The Suzanne Wright Foundation proposed a national health policy initiative to establish HARPA, the Health Advanced Research Projects Agency. HARPA would exist with HHS and leverage federal research assets and private sector tools to drive medical breakthroughs for diseases, like pancreatic cancer, that have not benefited from the current system. HARPA is modeled after the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the gold-standard for innovation and accountability. DARPA, an agency within the Department of Defense, developed The Internet, Voice Recognition Technology, GPS navigation, Night vision, Robotic Prostheses, Stealth Technology. DARPA's success proves there is an effective government model for translating science to product. HARPA's identical operating principles, built on urgency, leadership, high-impact investments and accountability, would advance scientific research "from bench to bedside." HARPA would work within an innovation ecosystem that includes: the commercial market; biotech and healthcare companies; venture capital and philanthropy; academic institutions; and other government and regulatory agencies.[53]

On May 22, 2018, The Suzanne Wright Foundation premiered their film The Patients Are Waiting: How HARPA Will Change Lives, in New York City. The film screening was followed by a panel hosted by Maria Bartiromo, Anchor and Global Markets Editor, FOX Business Network – FOX News Channel. Panelists included Bob Wright, Dr. Herbert Pardes, Executive Vice Chairman of NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital; Former Director NIMH, Dr. Geoffrey Ling, Col. (Ret.) Prof. of Neurology, Johns Hopkins; Founder & Former Director, DARPA BTO, Jessica Morris, Co-founder of OurBrainBank, and Karen Reeves, President & CMO, AZTherapies.

On March 15, 2022, Public Law 117-103 was enacted authorizing the establishment of ARPA-H within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.[13]

Lee Equity Partners

editLee Equity Partners, a private equity firm run by financier Thomas H. Lee, announced in January 2008 that Wright would join the company as a senior advisor.[28] Due to Wright's background with GE Financial Services and NBC, Wright was brought on to advise in media and financial sector deals.[28][54]

Boards and affiliations

editWright has served on numerous boards, councils and committees. As of February 2016, he sits on the board of directors for Polo Ralph Lauren;[1] Autism Speaks, an autism advocacy group he co-founded with his wife Suzanne;[47] AMC Networks;[2] Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation;[55] and Palm Beach Fellowship of Christians & Jews.[56] He is chairman and CEO of Palm Beach Civic Association.[4] He is a life trustee of the New York-Presbyterian Hospital.[3]

Honors and awards

editWright has accepted various awards and honors during his career in media. He was inducted into the Broadcasting & Cable Hall of Fame in 1996,[57] the Cable Center's Cable Hall of Fame in 2007[58] and AAF's Advertising Hall of Fame in 2009.[59] He received the "Gold Medal Award" from International Radio & Television Society Foundation in 1997,[60] the "Steven J. Ross Humanitarian of the Year Award" of UJA-Federation of New York in 1998,[61][62] "Public Service Award" from the Ad Council in 2002,[63] Broadcasters' Foundation's "Golden Mike Award" in 2003,[64] Media Institute's 2004 "Freedom of Speech Award",[65] "Humanitarian Award" from the Simon Wiesenthal Center in 2005,[24] "Distinguished Leadership in Business Award" from Columbia Business School in 2005,[66] and the "Visionary Award" from the Museum of Television & Radio in 2006.[67] He also was awarded the Minorities in Broadcasting Training Program's "Striving for Excellence Award".[68] Wright and his wife Suzanne have been honored for their work with Autism Speaks. They were presented with the first-ever "Double Helix Medal" for Corporate Leadership from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory,[69] the New York University "Child Advocacy Award", the Castle Connolly "National Health Leadership Award" and the American Ireland Fund "Humanitarian Award".[70] They received the "Dean's Medal" from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health,[71] the "President's Medal for Excellence" at Boston College's Wall Street Council Tribute Dinner[69] and the "Visionary Award" at the 20th Annual Nantucket Film Festival.[72] The Wrights were named among Time's 100 most influential people in the world in 2008.[73]

Bibliography

edit- Wright, Bob; Mermigas, Diane (2016). The Wright Stuff: From NBC to Autism Speaks. RosettaBooks. ISBN 978-0-7953-4692-7.

Personal life

editWright was married to his wife Suzanne from 1967 until her death from pancreatic cancer in 2016.[74][75] He has three children, Katie, Chris, and Maggie[8] and six grandchildren: Christian, Mattias, Morgan, Maisie, Alex, and Sloan.[76] He married his second wife, Susan Goldwater Keenan, on Sept. 30, 2017.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Ralph Lauren Corp. (RL)". Reuters. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ a b "AMC Networks Inc. (AMCX)". Reuters. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ a b "Life Trustees at New York-Presbyterian Hospital". New York-Presbyterian Hospital. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ a b "Directors and members". Palm Beach Civic Association. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Michael Reardon (2005). "The Profile: Robert C. Wright '65". Holy Cross Magazine. College of the Holy Cross. Archived from the original on December 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Ensher, Ellen A.; Murphy, Susan E. (2011). Power Mentoring: How Successful Mentors and Proteges Get the Most of Their Relationships. John Wiley & Sons. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-118-04687-6.

- ^ a b c Lowry, Brian (April 25, 2013). "Former NBC topper Bob Wright stayed ahead of the curve on biz changes". Variety. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Gunther, Marc (February 3, 1997). "How GE made NBC No. 1". Fortune. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Executive Profile: Robert C. Wright". Bloomberg. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e McKenna, Josephine (November 21, 2014). "Pope Francis tackles autism as families seek hope and support". Deseret News. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ "Grieving Husband Launches Foundation to Fight Pancreatic Cancer in Honor of His Late Wife". People. November 16, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "About". HARPA. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ a b "ARPA-H". National Institutes of Health (NIH). Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ Wright, Bob; Mermigas, Diane (2016). The Wright Stuff: From NBC to Autism Speaks. RosettaBooks. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7953-4692-7.

- ^ Wright, Bob (2003), "No profession is more honorable than the law" (PDF), UVALawyer, p. 69, archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2016, retrieved February 8, 2016

- ^ a b "GE names NBC president vice chairman". Bloomberg News. July 29, 2000. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor III, Alex (March 16, 1987). "GE's hard driver at NBC". Fortune. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Egan, Jack (October 6, 1978). "GE and Cox Broadcasting plan merger". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ Jones, William H. (February 27, 1979). "Mutual agrees to buy N.Y. radio station". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ Fabrikant, Geraldine (December 13, 1992). "For NBC, hard times and miscues". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c Sharbutt, Jay (August 22, 1986). "Wright seen as next NBC chief". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "Cox Cable's Wright: Building the future" (PDF). Broadcasting Now. November 1, 1982. p. 87. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "The Hauser Oral and Video History Project: Bob Wright". Syndeo Institute at The Cable Center. May 15, 2007. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Biography: Bob Wright". PBS. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ Siklos, Richard; Holson, Laura M. (August 8, 2005). "NBC Universal aims to be prettiest feather in G.E.'s cap". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Boyer, Peter J. (June 6, 1988). "NBC Tries a Quieter Way of Breaking into Cable TV". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "Ex-NBC head Wright joins Lee Equity". Los Angeles Times. February 1, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Ex-NBC chair to join Lee Equity Partners". The New York Times. January 31, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Mermigas, Diane (December 4, 2000). "NBC continues to thrive in GE's world". Electronic Media. p. 38.

- ^ Sherman, Alex; Bass, Dina (July 16, 2012). "MSNBC website renamed NBCNews.com after Microsoft split". Bloomberg News. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Tim (June 9, 1996). "NBC prepares for '90s, and beyond". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Hofmeister, Sallie (November 5, 2002). "NBC to add new content to Bravo". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Wharton, Dennis (March 29, 1994). "Wright set to argue for easing regs". Variety. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Flint, Joe (January 17, 1994). "Facing the facts of life in a post fin-syn world". Broadcasting & Cable. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Carter, Bill (May 13, 2004). "Deal compete, NBC is planning to cross-market". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Cendrowicz, Leo (January 31, 2007). "NBC's Wright" Put anti-piracy at top of agenda". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "Media Institute Speeches". Media Institute. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Wright, Bob (November 8, 2005). "Stop IP theft". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Wright, Bob (2005). "Technology and the Role of Law in the Digital Age". Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy. 19 (2): 705–710. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Kador, John (2004). 50 High-Impact Speeches and Remarks. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 121–128. ISBN 0-07-142194-7.

- ^ "Chief executive says GE won't sell NBC Universal". Associated Press. March 12, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "Notice of 2008 Annual Meeting and Proxy Statements" (PDF). General Electric. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "Cable Hall of Fame Honoree 2007 | Robert C. Wright". Syndeo Institute at The Cable Center. 2007. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "Autism Speaks". philanthropynewsdigest.org. Foundation Center. April 15, 2008. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Lee, Hailey (November 6, 2014). "Ex-NBC chief Bob Wright paves way for autism research". CNBC. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ "'MSSNG' project, partnership between Autism Speaks and Google for autism research, has official launch". ABC News. December 9, 2014. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ a b Michelle Diament (May 5, 2015). "Autism Speaks sees leadership change". Disability Scoop. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "Board members". Autism Speaks. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Foundation, The Suzanne Wright. "Bob Wright Launches The Suzanne Wright Foundation to Fight Pancreatic Cancer" (Press release). PR Newswire. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Stanton, John. "Bob Wright takes on pancreatic cancer after losing wife Suzanne". The Inquirer and Mirror. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "Can Pancreatic Cancer Be Found Early?". cancer.org. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "American Cancer Society | Cancer Facts & Statistics". American Cancer Society | Cancer Facts & Statistics. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "About". HARPA. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Kouwe, Zachery (February 1, 2008). "Bob Wright to advise on media for buyout big". New York Post. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "Board of directors". Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "Who we are". Palm Beach Fellowship of Christians & Jews. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "Benefits". The New York Times. November 3, 1996. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ "Broadband briefs". CED. April 12, 2007. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ "Advertising Hall of Fame Members". Advertising Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ "Billboard". Billboard. March 29, 1997. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ "UJA-Federation of New York". UJA-Federation of New York. Archived from the original on January 22, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ "Billboard". Billboard. October 4, 1997. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ "Adweek Calendar". Adweek. November 18, 2002. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ "Mike Bloomberg to receive Golden Mike Award". Broadcasting & Cable. December 22, 2009. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Kaplan, David (October 28, 2004). "NBC's Wright cites erosion of intellectual property rights". MediaPost Communications. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ "Distinguished Leadership in Business Award". Columbia Business School. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Paul J. Gough (February 3, 2006). "NBC Chairman and 'SNL' Honored at Gala". Backstage. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ "SFE Awards". MIBTP. April 30, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ a b "Cable Hall of Fame 2007 Honorees | Robert C. Wright". Syndeo Institute at The Cable Center. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "A Strong Voice: An interview with Suzanne and Bob Wright, co-founders, Autism Speaks". Leaders Magazine. April 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Gouveia, Georgette (October 31, 2014). "Autism Speaks and Suzanne and Bob Wright ensure the world listens". WAG Mag. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Gerard, Jeremy (May 14, 2015). "Robert Towne will be feted at 20th Nantucket Film Fest". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Brokaw, Tom (May 12, 2008). "The 2008 Time 100". Time. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ O'Brien Mackey, Sarah (Spring 2006). "Inspired to make a difference: Bob Wright '65" (PDF). Holy Cross Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ Kauffman, Ellie (July 30, 2016). "Suzanne Wright, autism advocate, dies at 69". CNN. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ^ "About the author". RosettaBooks. Retrieved April 4, 2016.