In Muslim tradition the Quran is the final revelation from God, Islam's divine text, delivered to the Islamic prophet Muhammad through the angel Jibril (Gabriel). Muhammad's revelations were said to have been recorded orally and in writing, through Muhammad and his followers up until his death in 632 CE.[1] These revelations were then compiled by first caliph Abu Bakr and codified during the reign of the third caliph Uthman[2] (r. 644–656 CE) so that the standard codex edition of the Quran or Muṣḥaf was completed around 650 CE, according to Muslim scholars.[3] This has been critiqued by some western scholarship, suggesting the Quran was canonized at a later date, based on the dating of classical Islamic narratives, i.e. hadiths, which were written 150–200 years after the death of Muhammad,[4] and partly because of the textual variations present in the Sana'a manuscript. Muslim scholars who oppose the views of the Western revisionist theories regarding the historical origins of the Quran have described their theses as "untenable".[5]

More than 60 fragments including more than 2000 folios (4000 pages) are so far known as the textual witnesses (manuscripts) of the Qur'an before 800 CE (within 168 years after the death of Muhammad), according to Corpus Coranicum.[6] However, in 2015, experts from the University of Birmingham discovered the Birmingham Quran manuscript, which is possibly the oldest manuscript of the Quran in the world. Radiocarbon analysis to determine the age of the manuscript revealed that this manuscript could be traced back to some time between 568 and 645 AD.[7][8][9] Selected manuscripts from the first four centuries after the death of Muhammad (632–1032 CE) are listed below.

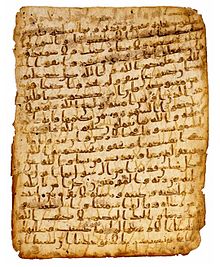

Hijazi manuscripts

editHijazi manuscripts are some of the earliest forms of Quranic texts, and can be characterized by Hijazi script.[1] Hijazi script is distinguished by its "informal, sloping Arabic script."[10] The most widely used Qurans were written in the Hijazi style script, a style that originates before Kufic style script. This is portrayed by the rightward inclining of the tall shafts of the letters, and the vertical extension of the letters.[11]

Codex Parisino-petropolitanus

editThe so-called Codex Parisino-petropolitanus formerly conserved portions of two of the oldest extant Quranic manuscripts. Most surviving leaves represent a Quran that is preserved in various fragments, the largest part of which are kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, as BNF Arabe 328(ab). Forty-six leaves are held at the National Library of Russia and one each in the Vatican Library (Vat. Ar. 1605/1) and in the Khalili Collection of Islamic Art.

BnF Arabe 328(c)

editBnF Arabe 328(c), formerly bound with BnF Arabe 328(ab), has 16 leaves,[12] with two additional leaves discovered in Birmingham in 2015 (Mingana 1572a, bound with an unrelated Quranic manuscript).[13] [14]

BnF Arabe 328(c) was part of a lot of pages from the store of Quranic manuscripts at the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Fustat bought by French Orientalist Jean-Louis Asselin de Cherville (1772–1822) when he served as vice-consul in Cairo during 1806–1816.

The 16 folia in Paris contain the text of chapter 10:35 to 11:95 and of 20:99 to 23:11.

The Birmingham folia covers part of the lacuna (gap) in the Paris portion, with parts of the text of suras 18, 19 and 20.

Birmingham Quran manuscript

editThe Birmingham Quran manuscript parchment of two leaves (cataloged as Mingana 1572a) has been radiocarbon dated to between 568 and 645 CE (95.4% credible interval), indicating the animal from which the parchment was made lived during that time.[7][8]

The parts of Surahs 18-20 its leaves preserve[15] are written in ink on parchment, using an Arabic Hijazi script and are still clearly legible.[8] The leaves are folio size (343 mm by 258 mm; 13½" x 10¼" at the widest point),[16] and are written on both sides in a generously scaled and legible script.[8] The text is laid out in the format that was to become standard for complete Quran texts, with chapter divisions indicated by linear decoration, and verse endings by intertextual clustered dots.

The two leaves are held by the University of Birmingham,[17] in the Cadbury Research Library,[7] but have been recognized[7][18][14] as corresponding to a lacuna in the 16 leaves catalogued as BnF Arabe 328(c)[19][20] in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, now bound with the Codex Parisino-petropolitanus.

Marijn van Putten, who has published work on idiosyncratic orthography common to all early manuscripts of the Uthmanic text type[21] has stated and demonstrated with examples that due to a number of these same idiosyncratic spellings present in the Birmingham fragment (Mingana 1572a + Arabe 328c), it is "clearly a descendant of the Uthmanic text type" and that it is "impossible" that it is a pre-Uthmanic copy, despite its early radiocarbon dating.[22]

Tübingen fragment

editIn November 2014, the University of Tübingen in Germany announced that a partial Quran manuscript in their possession (Ms M a VI 165), had been carbon dated (95.4% credible interval), to between 649 and 675.[23][24][25] The manuscript is now recognised as being written in hijazi script,[citation needed] although in the 1930 catalogue of the collection it is classified as "Kufic", and consists of the Quranic verses 17:36, to 36:57 (and part of verse 17:35).[26]

Sana'a manuscript

editThe Sana'a manuscript, is one of the oldest Quranic manuscripts in existence. It contains only three chapters. It was found, along with many other Quranic and non-Quranic fragments, in Yemen in 1972 during restoration of the Great Mosque of Sana'a. The manuscript is written on parchment, and comprises two layers of text (see palimpsest). The upper text conforms to the standard 'Uthmanic Quran, whereas the lower text contains many variants to the standard text. An edition of the lower text was published in 2012.[27] A radiocarbon analysis has dated the parchment containing the lower text to before 671 AD with 99% probability.[28]

Add. 1125

editThis manuscript was acquired by University of Cambridge from Edward H. Palmer (1840-1882) and EE Tyrwhitt Drake.[29] It was created before 800CE according to Corpus Coranicum.[29] It contains Quran from 8:10-72 written on 4 folios.[30]

Ms. Or. 2165

editBritish Library MS. Or. 2165 Early Qur'anic manuscript written in Ma'il script, 7th or 8th century CE.[31]

Codex Mashhad

editThe term Codex Mashhad refers to an old codex of the Qurʾān, now mostly preserved in two manuscripts, MSS 18 and 4116, in the Āstān-i Quds Library, Mashhad, Iran. The first manuscript in 122 folios and the second in 129 folios together constitute more than 90% of the text of the Qurʾān, and it is also likely that other fragments will be found in Mashhad or elsewhere in the world.[32] The current Codex is in two separate volumes, MSS 18 and 4116. The former contains the first half of the Qurʾān, from the beginning to the end of the 18th sūra, al-Kahf, while the latter comprises the second half, from the middle of the 20th sūra, Ṭāhā, to the end of the Qurʾān.[33] In their present form, both parts of Codex Mashhad have been repaired, partially completed with pieces from later Kufic Qurʾāns and sometimes in a present-day nashkī hand.[34]

Codex Mashhad has almost all the elements and features of the oldest known Qurʾānic codices. The dual volumes of the main body, written in ḥijāzī or māʾil script, are the only ḥijāzī manuscripts in vertical format in Iran. Like all ancient ḥijāzī codices, Codex Mashhad contains variant readings, regional differences of Qurʾānic codices, orthographic peculiarities, and copyists’ errors, partly corrected by later hands. The script and orthography of the Codex show instances of archaic and not-yet-completely-recognized rules, manifested in various spelling peculiarities. Illumination and ornamentation are not found even in sūra-headbands; rather, some crude sūra dividers have been added later and are found only on adjoining sections.[35]

It is also important to note the script in this manuscript is similar to Codex M a VI 165 at Tübingen (Germany), Codex Arabe 331 at the Bibliothèque Nationale (Paris), and Kodex Wetzstein II 1913 at Staatsbibliothek (Berlin). The combined radiocarbon dating of these manuscripts points firmly to the 1st century of hijra.

Kufic manuscripts

editKufic manuscripts can be characterized by the Kufic form of calligraphy. Kufic calligraphy, which was later named after art historians in the 19th or 20th century is described by means of precise upstanding letters. For a long time, the Blue Qur'an, the Topkapi manuscript, and the Samarkand Kufic Quran were considered the oldest Quran copies in existence. Both codices are more or less complete. They are written in the Kufic script. It "can generally be dated from the late eighth century depending on the extent of development in the character of the script in each case."[36]

The Blue Quran

editThe Blue Qur'an (Arabic: المصحف الأزرق al-Muṣḥaf al-′Azraq) is a late 9th to early 10th-century Tunisian Qur'an manuscript in Kufic calligraphy, probably created in North Africa for the Great Mosque of Kairouan.[37] It is among the most famous works of Islamic calligraphy,[37] and has been called "one of the most extraordinary luxury manuscripts ever created."[38] Because the manuscript was done in Kufic style writing, it is quite hard to read. "The letters have been manipulated to make each line the same length, and the marks necessary to distinguish between letters have been omitted."[39] The Blue Quran is constructed of indigo-dyed parchment with the inscriptions done in gold ink, which makes it one of the rarest Quran productions ever known.[39] The use of dyed parchment and gold ink is said to have been inspired by the Christian Byzantine Empire, due to the fact that many manuscripts were produced in the same way there.[39] Each verse is separated by circular silver marks, although they are now harder to see due to fading and oxidization.[39]

Topkapi manuscript

editThe Topkapi Qurʾān manuscript H.S. 32 is a significant Islamic artifact, notable for its size, script, and historical context. Originating from the middle 8th century,[40] this manuscript is preserved in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul. It showcases a unique style of Kufic script and is distinguished by its ornate decorations and intricate calligraphy. The manuscript has been the subject of scholarly study for its textual variants, providing insights into the early transmission and preservation of the Qurʾānic text.[41] Originally attributed to Uthman Ibn Affan (d. 656), However, a recent study published by De Gruyter has refuted this attribution by analyzing the manuscript's paleography and orthography. [42]

Samarkand Kufic Quran

editThe Samarkand Kufic Quran, preserved at Tashkent, is a Kufic manuscript, in Uzbek tradition identified as one of Uthman's manuscripts, but dated to the 8th or 9th century by both paleographic studies and carbon-dating of the parchment,[43][44] which showed a 95.4% probability of a date between 795 and 855.[44]

Gilchrist's dating of any Kufic manuscript to the later 8th century has been criticized by other scholars, who have cited many earlier instances of early Kufic and pre-Kufic inscriptions. The most important of these are the Quranic inscriptions in Kufic script from the founding of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem (692).[45] Inscriptions on rock Hijazi and early Kufic script may date as early as 646. The debate between the scholars has moved from one over the date origin of the script to one over the state of development of the Kufic script in the early manuscripts and in datable 7th-century inscriptions.

Codex Mixt. 917

editThis early Kufic Quranic manuscript is located in Austrian National Library. The codex came from Anatolia. It came into the possession of the Austrian ambassador to Constantinople Count Anton Prokesch-Osten in 1872 who gave it as a gift to the Austrian National Library. The manuscript dates to 700-725 CE based on the style of punctuation, which was only used for a short amount of time. It contains Quran from 2:97-7:205 and Q 9:19-29 written on 104 folios.[46][47]

Gotthelf Bergsträßer Archive

editThis almost complete Quranic manuscript was photographed by Otto Pretzl in 1934 in Morocco. In recent years, a few folios from the manuscripts have been sold by private companies and were dated to the 9th century or earlier by Christie's.[48][49]

Other manuscripts

editThe Ma'il Quran

editThe Ma'il Quran is an 8th-century Quran (between 700 and 799 CE) originating from the Arabian peninsula. It contains two-thirds of the Qur'ān text and is one of the oldest Qur'āns in the world. It was purchased by the British Museum in 1879 from the Reverend Greville John Chester and is now kept in the British Library.[50]

Significance

editThe dating and text of early manuscripts of the Qur'an have been used as evidence in support of the traditional Islamic views and by sceptics to cast doubt on it. The high number of manuscripts and fragments present from the first 100 years after the reported canonization have made the text one ripe for academic discussion. Founder of the revisionist Islamic studies movement in the mid 20th century, John Wansbrough, used the content in the Qur'an as a reference point for ascertaining that it was likely influenced by the Umayyad court, and believed its canon to have likely happened around the same time as that of the Islamic Hadith movement.[51] Although never the dominant academic view, with the advent of radiocarbon dating, the view is currently held only by a few scholars.[52] The more recently uncovered Birmingham Quran manuscript holds significance amongst scholarship because of its early dating and potential overlap with the lifetime of Muhammad c. 570 to 632 CE[53] (the proposed radiocarbon dating gives a 95.4% probability that the animal whose skin made the manuscript parchment was killed sometime between calendar years 568–645 CE). The text's identical reflection of the contemporary standard text of the Quran has generally lent credence to early Muslim narratives and provided a retort for historic criticisms levied at the text.[54][55] Emilio Platti, Professor Emeritus at the Catholic University of Leuven, for example holds that "scholars largely refuse today the late dating of the earliest copies of the Qurʾān proposed for example by John Wansbrough".[56] David Thomas, professor of Christianity and Islam at the University of Birmingham, states that "the parts of the Qur’an that are written on this parchment can, with a degree of confidence, be dated to less than two decades after Muhammad’s death."[7]

Joseph Lumbard also claims that the dating renders "the vast majority of Western revisionist theories regarding the historical origins of the Quran untenable," and quotes a number of scholars (Harald Motzki, Nicolai Sinai) in support of "a growing body of evidence that the early Islamic sources, as Carl Ernst observes, 'still provide a more compelling framework for understanding the Qurʾan than any alternative yet proposed.'"[5]

Behnam Sadeghi and Uwe Bergmann write that the Sana'a manuscript is unique among extant early Quranic manuscripts, "the only known manuscript" that "does not belong to the 'Uṯmānic textual tradition".[28] Those Hijazi manuscript fragments belonging to the "'Uṯmānic textual tradition" and dated by radio-carbon to the first Islamic century are not identical. They fall "into a small number of regional families (identified by variants in their rasm, or consonantal text), and each moreover contains non-canonical variants in dotting and lettering that can often be traced back to those reported of the Companions"[33]

Michael Cook[57] and Marijn van Putten[21] have provided evidence that the regional variants of the early Hijazi manuscript fragments share a "stem" and thus likely "descend from a single archetype", (that being Uthmanic codex in traditional Islamic history).

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Cohen, Julia (2014). "Early Qur'ans (8th-Early 13th Century)". The Met Museum.

- ^ Nöldeke, Theodor; Schwally, Friedrich; Bergsträsser, Gotthelf; Pretzl, Otto (2013). "The Genesis of the Authorized Redaction of the Koran under the Caliph ʿUthmān". In Behn, Wolfgang H. (ed.). The History of the Qurʾān. Texts and Studies on the Qurʾān. Vol. 8. Translated by Behn, Wolfgang H. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 251–275. doi:10.1163/9789004228795_017. ISBN 978-90-04-21234-3. ISSN 1567-2808. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Cook (2000): p. 6

- ^ Berg (2000): p. 495

- ^ a b Lumbard, Joseph E. B. (24 July 2015). "New Light on the History of the Quranic Text?". Huffington Post. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Its official website says: "Mehr als 60 Fragmente mit insgesamt mehr als 2000 Blättern (4000 Seiten) sind als Textzeugen für den Koran vor 800 bisher bekannt." https://corpuscoranicum.de/

- ^ a b c d e "Birmingham Qur'an manuscript dated among the oldest in the world". University of Birmingham. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d "'Oldest' Koran fragments found in Birmingham University". BBC. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ "Birmingham Qur'an manuscript dated among the oldest in the world". University of Birmingham. 22 July 2015. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Hannah, Korn (2012). "Scripts in Development". Metmuseum.org.

- ^ Blair, Sheila (1998). Islamic Inscriptions. New York University.

- ^ "Coran" – via gallica.bnf.fr.

- ^ "Birmingham Qur'an manuscript dated among the oldest in the world". University of Birmingham. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ a b "' The Qur'anic Manuscripts of the Mingana Collection and their Electronic Edition'". Quranic Studies Association Blog. 18 March 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Tests show UK Quran manuscript is among world's oldest". CNN. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ "The Birmingham Qur'an Manuscript - University of Birmingham". www.birmingham.ac.uk.

- ^ "Virtual Manuscript Room". University of Birmingham. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (22 July 2015). "Oldest Quran fragments found at Birmingham University". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Déroche, François (2009). La transmission écrite du Coran dans les débuts de l'islam: le codex Parisino-petropolitanus. Brill Publishers. p. 121. ISBN 978-9004172722.

- ^ "Ms. Paris BnF Arabe 328 (c)". Corpus Coranicum. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ a b van Putten, M. (2019). "The 'Grace of God' as evidence for a written Uthmanic archetype: the importance of shared orthographic idiosyncrasies". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 82 (2): 271–288. doi:10.1017/S0041977X19000338. hdl:1887/79373. S2CID 231795084.

- ^ van Putten, Marijn (January 24, 2020). "Apparently some are still under the impression that the Birmingham Fragment (Mingana 1572a + Arabe 328c) is pre-Uthmanic copy of the Quran". Twitter.com. Twitter. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Tübingen University fragment written 20-40 years after the death of the Prophet, analysis shows". Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen. February 15, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ "Sensational Fragment of Very Early Qur'an Identified". Archived from the original on 2015-07-07. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- ^ "World's oldest Qur'an found in Germany". Iran Daily. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ "Kufisches Koranfragment". Universität Tübingen. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ Sadeghi, Behnam; Goudarzi, Mohsen (2012). "Ṣan'ā' 1 and the Origins of the Qur'ān". Der Islam. 87 (1–2). Berlin: De Gruyter: 1–129. doi:10.1515/islam-2011-0025. S2CID 164120434.

- ^ a b Sadeghi, Behnam; Bergmann, Uwe (2010). "The Codex of a Companion of the Prophet and the Qurʾān of the Prophet". Arabica. 57 (4). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 343–436. doi:10.1163/157005810X504518. JSTOR 25782619.

- ^ a b "Corpus Coranicum".

- ^ "Islamic Manuscripts : al-Qurʼān". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ "Codex B. L. Or. 2165 – A Qur'anic Manuscript From 1st Century Hijra". www.islamic-awareness.org. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ Karimi-Nia, Morteza (2019). "A New Document in the Early History of the Qurʾān Codex Mashhad, an ʿUthmānic Text of the Qurʾān in Ibn Masʿūd's Arrangement of Sūras". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 10 (3): 293. doi:10.1163/1878464X-01003002. S2CID 211656087.

- ^ a b Karimi-Nia, Morteza (2019-11-01). "A New Document in the Early History of the Qurʾān: Codex Mashhad, an ʿUthmānic Text of the Qurʾān in Ibn Masʿūd's Arrangement of Sūras". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 10 (3): 294. doi:10.1163/1878464X-01003002. ISSN 1878-4631. S2CID 211656087.

- ^ Karimi-Nia, Morteza (2019-11-01). "A New Document in the Early History of the Qurʾān: Codex Mashhad, an ʿUthmānic Text of the Qurʾān in Ibn Masʿūd's Arrangement of Sūras". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 10 (3): 295. doi:10.1163/1878464X-01003002. ISSN 1878-4631. S2CID 211656087.

- ^ Karimi-Nia, Morteza (2019-11-01). "A New Document in the Early History of the Qurʾān: Codex Mashhad, an ʿUthmānic Text of the Qurʾān in Ibn Masʿūd's Arrangement of Sūras". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 10 (3): 301. doi:10.1163/1878464X-01003002. ISSN 1878-4631. S2CID 211656087.

- ^ John Gilchrist, Jam' al-Qur'an: The codification of the Qur'an text (1989), p. 146.

- ^ a b "Folio from the Blue Qur'an (Probably North Africa (Tunisia)) (2004.88)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. September 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "Folio From the Blue Qur'an". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Folio from the 'Blue Qur'an'". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Halaseh, Rami Hussein (2024-09-03), "The Topkapı Qurʾān Manuscript H.S. 32: History, Text, and Variants", The Topkapı Qurʾān Manuscript H.S. 32, De Gruyter, p. 83, doi:10.1515/9783111467320, ISBN 978-3-11-146732-0

- ^ Halaseh, Rami Hussein (2024-09-03), "The Topkapı Qurʾān Manuscript H.S. 32: History, Text, and Variants", The Topkapı Qurʾān Manuscript H.S. 32, De Gruyter, doi:10.1515/9783111467320, ISBN 978-3-11-146732-0, retrieved 2024-09-26

- ^ Halaseh, Rami Hussein (2024-09-03), "The Topkapı Qurʾān Manuscript H.S. 32: History, Text, and Variants", The Topkapı Qurʾān Manuscript H.S. 32, De Gruyter, pp. 81–83, doi:10.1515/9783111467320, ISBN 978-3-11-146732-0

- ^ "The "Qur'ān Of ʿUthmān" At Tashkent (Samarqand), Uzbekistan, From 2nd Century Hijra". Retrieved 2013-09-13.

- ^ a b E. A. Rezvan,"On The Dating Of An “'Uthmanic Qur'an” From St. Petersburg", Manuscripta Orientalia, 2000, Volume 6, No. 3, pp. 19-22.

- ^ The Arabic Islamic Inscriptions On The Dome Of The Rock In Jerusalem, islamic-awareness.org; also Hillenbrand, op. cit.

- ^ "Koran: Qurʾān". Austrian National Library(Österreichische Nationalbibliothek) (in German). Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ "Corpus Coranicum". corpuscoranicum.de. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ "A Kufic Quran Folio, Near East or North Africa 9th Century or earlier". Christie's. 6 April 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "A Kufic Quran Folio, Near East or North Africa 9th Century or earlier". Christie's. 9 October 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "The British Library's oldest Qur'an manuscript now online". British Library. 7 April 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Berg , "Methods and Theories of John Wansbrough", 2000: p.501-2

- ^ Shoemaker, Stephen J. (2022). "Radiocarbon Dating and the Origins of the Quran". Creating the Qur'an: A Historical-Critical Study. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-38903-8.

- ^ Elizabeth Goldman (1995), p. 63, gives 8 June 632, the dominant Islamic tradition. Many earlier (mainly non-Islamic) traditions refer to him as still alive at the time of the invasion of Palestine. See Stephen J. Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet: The End of Muhammad's Life and the Beginnings of Islam,[page needed] University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

- ^ Sayoud, H. (2018). "Statistical Analysis of the Birmingham Quran Folios and Comparison with the Sanaa Manuscripts" (PDF). International Journal of Hidden Data Mining and Scientific Knowledge Discovery. 4 (1).

- ^ Reynolds, Gabriel Said (7 August 2015). "Variant Readings: The Birmingham Qur'an in the Context of the Debate on Islamic Origins". Times Literary Supplement. pp. 14–15. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ Platti, Emilio (24 January 2017). "The oldest manuscripts of the Qurʾān". Institut dominicain d’études orientales. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Cook, M. (2004). "The Stemma of the Regional Codices of the Koran", Graeco-Arabica, 9-10

Sources

edit- Berg, Herbert (2000). "15. The Implications of, and Opposition to, the Methods and Theories of John Wansbrough". The Quest for the Historical Muhammad. New York: Prometheus Books. pp. 489–509.

- Böwering, Gerhard (2007). "Recent Research on the Construction of the Qur'an". In Reynolds, Gabriel (ed.). The Qur'an in its Historical Context. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203939604. ISBN 978-1-134-10945-6.

- Cook, Michael (2000). The Koran : A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192853449.

- Donner, Fred M. (2008). "The Quran in Recent Scholarship". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 29-50. ISBN 978-1-134-10945-6. Archived from the original on 2013-07-18.

- Wansbrough, J. (1978). Quranic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation (PDF). Oxford. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

edit- Déroche, François (1992). The Abbasid Tradition: Qur'ans of the 8th And 10th Centuries AD. Nour Foundation. ISBN 1-874780-51-X.