Bledington is a village and civil parish in the Cotswold district of Gloucestershire, England, about four miles southeast of Stow-on-the-Wold and six miles southwest of Chipping Norton. The population of the civil parish in 2014 was estimated to be 490.[1]

| Bledington | |

|---|---|

The green at Bledington | |

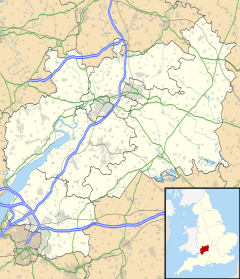

Location within Gloucestershire | |

| Population | 506 United Kingdom Census 2011 |

| OS grid reference | SP24752264 |

| • London | 82 mi (132 km) ESE |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Chipping Norton |

| Postcode district | OX7 |

| Dialling code | 01608 |

| Police | Gloucestershire |

| Fire | Gloucestershire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Bledington lies in the Evenlode valley, and forms part of the Gloucestershire–Oxfordshire boundary and stands on the Oxfordshire Way. There are deposits of alluvial soil, but most of the land is heavy clay, the parish being almost entirely on the Lower Lias.

The village is built round a rectangle of streets, with the church in the south corner, and the green, with most of the older houses near it, on the northwest side. The southern part of the village has been developed extensively since 1920. The village green is a large unenclosed stretch of grass, with a stream running through it.

The parish church dates from the 12th century and was extended in the 15th century. The village has a county primary school which dates from the late 19th century. It has a pub, The Kings Head, on the village green. Its former shop and post office have long since closed, but a new community run shop was opened in 2019 Bledington Community Shop. The village hall, which stands near the centre of the village, is a converted 18th-century barn of rubble with a Cotswold stone roof. A trust was formed and the building was bought in 1920 for the use of the people of Bledington and Foscot hamlet.[2] It was renovated and re-roofed in 2016.

History

editAlthough Roman coins have been found near the centre of the parish, the settlement of Bledington (Bladinton, or Bladynton) was probably established in late Saxon times, taking its name from the nearby river Bladon (now the Evenlode), which forms the eastern boundary of the parish (and the county). With its heavy clay soil and poor drainage, Bledington seems to postdate nearby West Saxon manors situated on higher ground.[3] The manor of Bladintona is recorded as being among the gifts of Coenwulf of Mercia to the abbey of Winchcombe in 798,[4] and they retained the control for over 700 years until the abbey's dissolution in 1539.

There were 22 households in the manor in the Domesday survey in 1086, giving a population of about 100, but with no freemen and no priest (and, by implication, no church).[5] By this time, about half (7 hides) of the 1,539 acres of land in the parish were under cultivation. The first mention of the parish church is in 1175 (see below). Bledington was still small and poor enough to be coupled with Sherbourne in 1303 as forming a knight's fee for the purpose of raising a feudal aid for the wedding of Edward I's daughter.[6]

The general picture, then, of the village is of a rather wide-spread group of rather small houses, with chimnenyless roofs, thatched and shaggy, often surrounded by mud, owing to the un-drained clay-based ground. ... Set above all this, the church rises in the dignity of relatively high stone walls and moulded lofty windows.[7]

The Black Death arrived in England in 1348 and manor court records suggest that at least one in three Bledington villagers died.[7]: 50 The loss of income caused by the Black Death prompted the Abbot of Winchcombe to apply to the King, the Pope and the Bishop of Worcester for permission to appropriate the rectory in 1402, subordinating the resulting vicarage to the abbey and benefitting from the proceeds of the glebe and tithes.[8] In 1546, following the Dissolution, the rectory, including farm, tithes and offerings, was granted to the Dean and Chapter of Christ Church, Oxford.[9] The dean and chapter remained among the principal landowners in Bledington in the 19th century,[10] but by the mid-20th century most of their land had been sold piecemeal and only part of Village Farm was still owned by them.

In March 1553, the manor was acquired from the Crown for £897.13s.1+1⁄2d (25 times its rental income) as part of an investment package by Thomas Leigh, a wealthy London merchant.[11] At one stage the Leigh family owned the manors of Adlestrop, Maugersbury and Longborough, as well as their originating village of Stoneleigh.[12] Before the sale, a detailed survey of the manor was undertaken which reveals that there was pasturage for 870 sheep and 124 oxen. Arable land was being used for wheat, barley and pulse together with some hemp for spinning.[7]: 105

By 1600, Leigh's descendants had begun to sell parts of the estate, principally to its tenants, but these freeholds did not represent contiguous areas of land. A 1710 will reveals that one freeholder had 250 arable strips distributed in 207 locations.[7]: 137 The manorial common land was divided into parts, mostly held by yeomen whose ancestors had been customary tenants in the 16th century, but was still used as common pasture.[2]

In 1770 six open fields were enclosed, a total of 1,343 acres, with sixteen landowners receiving allotments. Although there was a certain amount of exchanging of land after enclosure, on the whole, the lands belonging to each farm remained scattered. At a second enclosure in 1831 an area of 179 acres was divided between nine proprietors.[13] In the 19th century, only Bledington Ground, and Village Farm remained large farms. The arable land produced wheat, oats, and barley,[14] and by the late 19th century turnips and cider apples were also being grown.[10] and earlier edns. By the mid-20th century, this industry had stopped owing to the cost of labour and lack of facilities for making cider locally, but the orchards were still a prominent feature of the landscape.

A mill at Bledington was recorded as part of Winchcombe Abbey's estate in the Domesday Book.[5] There was a miller in Bledington up to 1935.[15]

Parish church

editThe Church of St Leonard is the parish church dedicated to St Leonard. It is of stone, with roofs of lead and of Cotswold stone, and comprises a chancel with a sanctus bell-cot, clerestoried nave, south aisle, south porch, and embattled west tower. The church was lavishly rebuilt in the 15th century, though it retains earlier parts, and the 15th-century painted glass surviving in some of the windows is a notable feature.[16] The earliest known reference to a church in Bledington is in a confirmation dated 1175 by Pope Alexander III to Winchcombe Abbey of all its churches.[17] The east and west walls of the nave are said to be from this era.

The chancel, the nave arcade of three bays, and the south porch were built in the 13th century, and some new windows were added in the 14th century. Subsequently, a three-stage tower with an external vice was erected: the west wall of the nave serves as the base of the west wall of the tower and arches within the nave support the other walls of the tower.

The main rebuilding in the late 15th century included the raising of the nave roof, the insertion of a clerestory and parapets, and the refenestration of the nave and aisle. Most of the new windows were square-headed, with Perpendicular tracery, and five have canopied image brackets in each reveal. A recess with a three-light window was built leading from the south-west corner of the chancel into an archway to the south aisle. The 15th-century south doorway, with moulded arch and head stops, retains part of its early door. In 1548 Somerset, the Lord Protector, acting on behalf of the boy king Edward VI, ordered that all imagery should be removed from churches, and by 1650 St Leonards had lost its rood screen and window statues. The hidden remains of the earlier wall decorations are now partially visible, including a stretch of masonry pattern enriched with rosettes and heart-shaped petals dating from the 14th century on the west wall of the chancel and a late medieval figure, in black outline, of a crowned female saint with long hair on the east wall of the nave.[16]

The eight windows of the north wall of the nave and the recessed window in the south wall of the chancel were filled with contemporary painted glass. The glass survives, in some cases as fragments pieced together, but in others as nearly complete panels. It has been suggested[by whom?] that it was made by John Prudde of Westminster, glazier of the similar windows in the Beauchamp chapel in Warwick. Some of the inscriptions and names of donors can still be seen, one dated 1470.

The building was in a very poor state by the mid 19th century.[18] It was restored in 1881[10] by J. E. K. Cutts[19] and again by F. E. Howard c.1923. The pews were replaced in 1904,[10] but some 15th-century bench ends with decorative blind tracery were retained. The tub-shaped font is 12th-century, the communion rails and altar table are 17th-century, and beside the 20th-century pulpit is an ancient wrought-iron hourglass stand. There are five 17th-century bells and a sixth dated 1811. One bell cast in 1639 bears the inscription We are the bells of Bledington and Charles is our King.

The ecclesiastical parish includes both Bledington and the hamlet of Foscot in Oxfordshire and forms part of the Evenlode Vale benefice of the Anglican Church. The patronage remains with the Dean and Chapter of Christ Church.

Inn

editThere were two "alehouses" in 1775, and there were still two inns in 1870, but by 1889 the 16th-century King's Head was the only survivor. Overlooking the village green, it is a traditional village pub with dining and accommodation and was recognised as one of the ten best inns in the country by the Good Pub Guide in its 2018 edition.[20] It stands at the lowest part of the village and along with other low-lying houses can suffer from flooding. The parish council manages a water height monitor which is linked to an SMS text and email alert system providing early warning in the event of the water height rising and threatening these buildings.

Other notable buildings

editThe Steward's House in Chapel Lane, is reputed to have been built as a house for Winchcombe Abbey's manorial steward and dates from the 17th century. The interior was formerly a three-room plan with linking doors against the rear wall. The former central room retains a 2m section of a raised plasterwork frieze, the middle part of which is decorated with a vine scroll decoration: the upper margin features bursting seed pods and griffins, and the lower has foliate decoration. There is an inglenook fireplace with a moulded Tudor arched bressumer in same room.[21]

Manor Farm, possibly built on the site of a rest-house used by the monks of Winchcombe, has a 17th-century to early 18th-century T-shaped early core but was considerably enlarged c. 1900 by Guy Dawber and by more recent extensions.[16] It is built of coursed squared and dressed limestone with a limestone slate roof and ashlar stacks. As with other major houses in the area, it has two stories and an attic lit by dormer windows. The first floor has chamfered stone-mullioned casements with stopped hoods and the ground floor has metal casements to ground floor, all with leaded panes. The original central doorway, door and door surround has been repositioned in the early century extension and comprises a studded plank door with decorative hinges within a roll-moulded Tudor-arched surround with raised, carved spandrels, and thin pilasters to either side supporting rectangular pediment.[22]

Banks Farm is another classic Cotswolds stone farmhouse with elements dating back to the 17th century. It has two stone plaques on the front bearing witness to major rebuilding, in 1736 and 1784. These 18th-century extensions feature finely dressed limestone, a stone slate roof and ashlar stacks. Home Farm, across the Green, is also partly 17th-century. It is of two stories and attics, built of rubble with a Cotswold stone roof, and has mullions and dormers.

Five Bells Cottages, opposite the church, is said to have been an inn, at one time called the Five Tuns. It is mainly from 18th-century, but was extensively repaired in the 20th century.

There are other 18th-century buildings, including Beckley House adjacent to Manor Farm and Little Manor facing the Green, both of which have a symmetrical ashlar front, and Gilberts Farmhouse, also on the Green, which was originally two semidetached houses. The Old Bakery on the Green is dated 1741.[16]

There are several brick buildings dating from the 19th century when there was a brickworks in the parish. These include The Old Vicarage, erected c. 1845 and extended in 1865 and 1915, with stone dressings and a hipped slate roof,[16] as well as some groups of cottages, a few substantial houses on the road to Kingham, several barns, as well as the school and the former Methodist chapel.

Bledington School

editBledington has its own primary school, Bledington School, which was awarded 'Outstanding' by OFSTED in 2011, putting it in the top 9% of primary schools nationally. There has been a day school in Bledington since In 1819, and by 1871 there were two schools, of which one was associated with the Church of England, and the other was non-denominational.[2] The current school building "costing over £900",[10] integrated with a residence for its master, was constructed when a school board for the parish was established in 1874. From 1877 the school received a state grant.

Bledington Community Shop And Café

editIn late 2019, after 10 years of fundraising by the local community, Bledington's community-owned shop and cafe replaced Bledington's village shop that closed in 2006. Bledington Shop and Cafe is owned by more than 360 residents of Bledington through Bledington Community Shop Ltd, an industrial and provident society. A charity, Bledington and Foscot Community Association, has been established. Over £350,000 was raised to launch the shop. Bledington Community Shop and Café is run by local volunteers and a paid manager. The Post Office part of the shop now operates in the King's Head two mornings each week.

Bledington Music Festival

editThe Bledington Music Festival is an annual classical music event which takes place over three summer evenings in June and features top class performers from all over the world. The Festival was established in 2000.

Bledington and Foscot News

editBledington and Foscot News is a magazine containing local news and events, is distributed monthly and is subsidised by local donations. The most recent editions can be found on the village website.

Awards

editThe village won the Community category of the "2004 Calor Gloucestershire Village of the Year". The judges "were very impressed with the amount of activity in the community, considering the fact that the population is under 400. Its ability to run a large number of community events, ranging from the annual village fete to two flower shows and a music festival is impressive – as is the range of activities which take place in the village hall. We were also impressed with the provision the village makes for older people through the local church’s Care Committee and with the fact that it supports a village shop."

In 2012 the village won the Most Resilient Community category of the Gloucestershire Rural Community Council Vibrant Village Awards.

Morris dancing

editThe name Bledington is well known by Morris dancers, even though the dances are seldom seen in the village today. The area is rich in Morris history, with performances recorded in Sherborne in 1711 and Churchill when a Morris team were paid six shillings for dancing at a Whitsun Ale in 1721.[23] There is also evidence that sides were active in Rissington, Icomb and Milton all close Bledington, in the late 1700s. Each village had its own steps and tunes, and the best-known are those that were collected by Cecil Sharp in the villages on the uplands of Gloucestershire and neighbouring counties.

No recorded incidents of Morris dancing in Bledington itself exist before the mid-19th century, when a side from Bledington were remembered as having danced here and at nearby Fifield. The style now known as Bledington probably first entered the records with John Lainchbury, a farm labourer from Rissington who was the senior member of a set dancing in Idbury between 1850 and 1870.

Charles Benfield began playing the pipe and tabour for the Morris in the 1850s and 'inherited' the instruments from the renowned Sherborne and Northleach musician Jim 'the laddie' Simpson. Benfield eventually went on to become a key character in the local Morris, playing for Milton, Idbury, Fifield and Longborough. By the 1880s, Benfield found it difficult to maintain a complete side, but dancing continued sporadically until the late 1890s. He ensured a link which touched almost four generations of dancers that enabled the dances to be recorded by Sharp and later demonstrated and refined by the Travelling Morrice, a group formed in Cambridge in the 1920s. To date, some 39 Bledington dances have been collected.[24]

Transport

editRoad

editThe B4450, a secondary road linking Stow-on-the-Wold with Chipping Norton, runs through Bledington, near Kingham and through Churchill Village. Through traffic usually uses the faster A436 between Stow-on-the-Wold with Chipping Norton, due to the shorter distance and a 5-minute saving in journey time.

Rail

editThe village is a short walk from Kingham station which has trains running to Oxford, London and Worcester.

Further reading

editThe history of Bledington between the Norman Conquest and the beginning of the Great War is chronicled by M. K. Ashby in her book The Changing English Village.[7]

It is also summarised in the Victoria County History entry for the parish.[2]

References

edit- ^ Mid-Year Estimates (ONS) 2014 cited in Oxford Consultants for Social Inclusion (9 November 2016). "Local Insight profile for 'Bledington CP' area". Gloucestershire Parish Profiles. Gloucestershire County Council. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Elrington, CR, ed. (1965). "Bledington". History of the County of Gloucester. Victoria County History. Vol. 6. London: British History Online. pp. 27–33. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Royce, David (1882). ""Finds" near Stow" (PDF). Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archeological Society. vii: 69–80.

- ^ Dugdale, William; Caley, John; Ellis, Henry; Bandinel, Bulkeley (1846). "De Praediis, Dominiis, et Possessionibus per beatissima Regem Kenulphum Winchelcumbensi Monastario collatis" [Of estates, ownership, and properties bestowed on Winchcombe Monastery by the most blessed King Coenwulf]. Monasticon Anglicanum: A New Edition. Vol. ii. London: James Bohn. p. 302.

- ^ a b "Gloucestershire, Page 8". Open Doomsday. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Inquisitions and assessments relating to feudal aids, with other analogous documents preserved in the Public record office; A.D. 1284-1431. Vol. ii. London: HMSO. 1900. p. 252.

- ^ a b c d e Ashby, M.K. (1974). The Changing English Village. Kington: The Roundwood Press. ISBN 0900093358.

- ^ Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, Vol II. London: HMSO. 1905. p. 491.

- ^ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII. Vol. xxi(2) Sep 1546 - Jan 1547. London: HMSO. 1910. p. 334.

- ^ a b c d e Kelly's Directory of the County of Gloucestershire (13th ed.). London: Kelly's Directories Ltd. 1914. p. 51.

- ^ Letters patent granting Thomas Leigh the manors of Castelthorpe and Bladington, etc., 11 March 1553. Shakespeare Birthplace Trust Collection DR18/1/1405

- ^ Bindoff, S.T. "LEIGH, Rowland (d. by 17 June 1603), of Longborough, Glos". The History of Parliament. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Gloucestershire Records Office. Q/RI 26

- ^ "Acreage Returns, 1801", Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. lxvii: 175

- ^ Kelly's Directory for Gloucestershire. London: Kelly's Directories Ltd. 1935. p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e Verey, David; Brooks, Alan (1999). Gloucestershire 1: The Cotswolds. Pevsner Architectural Guides, The Buildings of England. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300096040.

- ^ Winchcombe Abbey (1892). Royce, David (ed.). Landboc: sive registrum monasterii Beatea Mariae Virginis et Sancti Cénhelmi de Winchelcumba, in comitatu Gloucestrensi, ordinis Sancti Benedicti : e codicibus mss. penes praenobilem dominum de Sherborne. Vol. 1. Exeter: William Pollard & Co. p. 24.

Alexander episcopus, servus servo rum Dei, dilectis filiis Henrico Abbati et fratribus de Winchccumba, salutem et apostolicam benedictionem. Justis petentium desideriis dignum est nos facilem prebere consensum, et vota que a rationis tramite non discordant, effectu sunt prosequente complenda. Ea propter, dilecti in domino filii, vestris justis postulacionibus grato concurrentis assensu : ... ecclesiam de Bladintona ... sicut eas rationabiliter possidetis, vobis et ecclesie vestre auctoritate apostolica confirmamus et presentis scripti patrocinio communimus. (Alexander, bishop, servant of the servants of God, to beloved sons abbot Henry and the brothers of Winchcombe, greeting and apostolic blessing. Justly making an appropriate petition, it is without difficulty that we respond, and moreover to avoid disagreement, effect the following arrangement. Therefore, beloved in the Lord, your just demands are agreed: ... the church of Bledinton ... is clearly reasonable for you to hold; to you and your bishop apostolic authority is confirmed and your rights protected by this document.)

- ^ "St Leonard's Church, Bledington, Gloucestershire". The Church Builder. lvii. London: Gilbert and Rivington: 204. 1876.

For the last three centuries ... this remarkable fabric has been left ... to desolation and decay.

- ^ Cutts, J Edward K (1883). "Bledington Church" (PDF). Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. vii: 81–86.

- ^ "The Good Pub Awards 2018". The Good Pub Guide. Ebury Publishing. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "The Stewards House and Manor Cottage (Bledington) (1154568)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Manor Farm (Bledington) (1089810)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ Recorded by William 'Strata' Smith; see his Genealogical papers[permanent dead link], Oxford University Museum of Natural History (shelf-mark WS/A/2/2).

- ^ "Bledington Tradition". The Morris Ring. Retrieved 22 August 2017.