Blank Generation is the debut studio album by American punk rock band Richard Hell and the Voidoids. It was produced by Richard Gottehrer and released in September 1977 on Sire Records.

| Blank Generation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | September 1977 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 39:44 | |||

| Label | Sire | |||

| Producer | ||||

| Richard Hell & the Voidoids chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Alternate cover | ||||

1990 CD reissue cover | ||||

Background

editKentucky-born Richard Meyers moved to New York City after dropping out of high school in 1966 aspiring to become a poet. He and his best friend from high school, Tom Miller, founded the rock band the Neon Boys, which became Television in 1973.[1] They changed their names: Miller became Tom Verlaine, after the Symbolist Paul Verlaine, and Meyers became Richard Hell. The group was the first rock band to play the club CBGB, which soon became a breeding ground for the early punk rock scene in New York.[1] Hell had an energetic stage presence and wore torn clothing held together with safety pins and spiked his hair;[2] in 1975, after a failed management deal with the New York Dolls, impresario Malcolm McLaren brought some of Hell's ideas back with him to England and eventually incorporated them into the Sex Pistols' image.[3]

Disputes with Verlaine led to Hell's departure from Television in April 1975, and he co-founded the Heartbreakers with New York Dolls guitarist Johnny Thunders and drummer Jerry Nolan. Hell lasted less than a year with this band,[4] and began recruiting members for a new one in early 1976.[5] For guitarists, Hell found Robert Quine and Ivan Julian—Quine had worked in a bookstore with Hell, and Julian responded to an advertisement in The Village Voice. They lifted drummer Marc Bell from Wayne County. The band was named the Voidoids after a novel Hell had been writing.[5]

Hell drew musical inspiration from acts such as Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the Stooges and fellow New Yorkers the Velvet Underground, a group with a reputation for heroin-fueled rock and roll with poetic lyrics.[a][7] Hell also drew from—and covered—garage rock bands such as the Seeds and the Count Five, both found on the 1972 Nuggets compilation.[8]

Hell had written the song "Blank Generation" while still in Television; he had played it regularly with the band since at least 1974, and later with the Heartbreakers.[9] The Voidoids released a 7" Blank Generation EP in November 1976 on Ork Records[5] containing "Blank Generation", "Another World" and "You Gotta Lose". The cover featured a black-and-white photo by Hell's former girlfriend and unofficial CBGB photographer Roberta Bayley, depicting a bare-chested Hell with an open jeans zipper.[10] It was an underground hit, and the band signed to Sire Records for its album debut.[11] Bell eventually left and became a member of the Ramones in 1978, adopting the stage name Marky Ramone.

Recording

editThe album was co-produced by Richard Gottehrer, a songwriter associated with the Brill Building who co-penned his first hit in 1963 with "My Boyfriend's Back" and who performed in the group the Strangeloves, known for hits such as "I Want Candy".[12]

According to Hell, they recorded and mixed the entire album at Electric Lady Studios in New York City across three weeks beginning on March 14, 1977. Two months later, they were informed that the album release would be delayed until September because their label, Sire Records, was changing distributors. "In the meantime, I had noticed a lot of things about the record that I thought we could have done better," recalls Hell. He asked their label if they could re-record the album, and after getting their approval, they booked three weeks in late June and early July at Plaza Sound Studio, located on the eighth floor of Radio City Music Hall. The final LP would use the Plaza Sound recordings for every song except "Liars Beware," "New Pleasure" and "Another World," where the Electric Lady recordings were retained. Their rendition of John and Tom Fogerty's "Walking on the Water" was also added to the LP during the Plaza Sound sessions; the song had been added to their repertoire after it debuted during a CBGB performance on April 14, 1977.[13]

Final mixing began at Plaza Sound on July 13, but their work was interrupted a little after 9:00 p.m. by the New York City blackout of 1977. Electricity would not be restored until the next day, and mixing wouldn't resume until July 18 when all remaining studio work was completed on the same day.[13]

Both Quine and Julian played Fender Stratocasters through Fender Champ amplifiers.[14] Quine is usually panned to the right and Julian to the left in the mix, but their positions are reversed on "New Pleasure" and "Down at the Rock and Roll Club." On "Liars Beware" Julian plays through both channels as he played his rhythm part twice, with slightly heavier playing on the left. Quine plays all the solos except for "Liars" and "Another World," which Julian does. Julian does all of the soloing on "Another World" except during the outro, where both Julian and Quine play at the same time.[13] Mixed in the center were Bell's drums and Hell's bass and vocals.[14]

Analysis

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2014) |

To me, blank was a line where you can fill in anything ... It's the idea that you have the option of making yourself anything you want, filling in the blank. And that's something that provides a uniquely powerful sense to this generation. It's saying 'I entirely reject your standards for judging my behavior'.

Julian opens "Blank Generation" with a riff loosely inspired by the Who's 1970 song "The Seeker". The rest of the band joins one by one until Quine's short lead ends in feedback. The main section of the song features lyrics reflecting the hopelessness of his generation against a descending chord progression patterned after "The Beat Generation", a 1959 novelty song by Bob McFadden and poet Rod McKuen,[16] the descent matched with falsetto "ooh-ooh" backing vocals.[17] Quine takes two guitar solos—the first eight bars, the second 16—exhibiting his peculiar atonal mix of 1950s rock and roll with 1960s free jazz.[18] The song closes with a falsetto, doo-wop-like "Whee-ooh!"[19] which had been suggested by Johnny Thunders.[13]

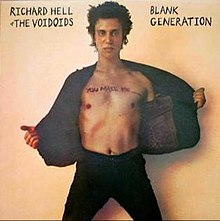

Cover design

editThe original album sleeve features a front cover photo by Bayley of a shirtless Hell in black jeans, opening a frayed jacket to reveal the phrase "YOU MAKE ME _______" written across his chest. The back cover featured a posed photo of Hell and the Voidoids taken by Kate Simon.[citation needed] Hell's hair was spiked, a look he attributed to Rimbaud.[20]

Critical reception

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [21] |

| Christgau's Record Guide | A−[22] |

| Classic Rock | 9/10[23] |

| Melody Maker | [24] |

| Mojo | [25] |

| Q | [26] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [27] |

| Select | 4/5[28] |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 8/10[29] |

| Uncut | 9/10[30] |

In a contemporary review of Blank Generation, Robert Christgau of The Village Voice wrote that the Voidoids "make unique music from a reputedly immutable formula, with jagged, shifting rhythms accentuated by Hell's indifference to vocal amenities like key and timbre", and that he intended "to save this record for those very special occasions when I feel like turning into a nervous wreck."[31]

In the first edition (1979) of The Rolling Stone Record Guide, Dave Marsh rated it 2 stars out of 5 and described it as "bull-oney", writing "In the first place, Jack Kerouac said everything here first, and far better. In the second place, Hell is about as whining as Verlaine is pretentious."[32] However, in a radical and uncharacteristic re-evaluation, the second edition (1983) replaced Marsh's review with one from Lester Bangs, who upped the rating to a full 5 stars, labeling it "seminal" and "essential to any modern music collection", and describing the music as "shattering assaults by a band that prophesied the later No Wave punk-jazz fusion".[33]

Ira Robbins of Trouser Press wrote that "the album combines manic William Burroughs-influenced poetry and raw-edged music for the best rock presentation of nihilism and existential angst ever. Hell's voice, fluctuating from groan to shriek, is more impassioned and expressive than a legion of Top 40 singers."[34]

Ben Ratliff of The New York Times later wrote that Blank Generation "helped define punk, so we're often told, but it's much more than that: it's literary, romantic (boy-girl), Romantic (intellectual tradition) and, because of Robert Quine's guitar solos, intensely musical, an album of high-grade improvisation."[35]

Mark Deming of AllMusic called Blank Generation "one of the most powerful [albums] to come from punk's first wave" and "groundbreaking punk rock that followed no one's template, and today it sounds just as fresh—and nearly as abrasive—as it did when it first hit the racks."[21] Sid Smith of BBC Music, in a 2007 retrospective review, called it "a thrilling and improbably poignant listening experience".[36]

1990 reissue

editThe 1990 compact disc reissue of Blank Generation differed in several respects from the original vinyl album. It sported a different cover, and included two bonus tracks: a version of the pop standard "All the Way" and an original, "I'm Your Man". Both were outtakes from the original album sessions. Also, the version of "Down at the Rock & Roll Club" was a noticeably different recording from that which appeared on the original album.

2017 reissue

editIn October 2017, it was announced that a 40th anniversary limited edition of the album would be released on CD and vinyl on November 24 for Record Store Day's Black Friday sale. The reissue, mastered by original engineer Greg Calbi, included a second disc of previously unreleased alternate takes, singles-only tracks and rare bootleg live tracks recorded at the band's first CBGB performance in 1976, as well as a booklet featuring an essay from Hell, an interview with Ivan Julian conducted by Hell, previously unpublished photos by Bayley, and snapshots of Hell's notebooks and private papers. [37]

Legacy

editRock critics have held Blank Generation in high regard. It has been highly influential, reflecting the kinds of themes that soon became commonplace in punk. Along with such groups as Television, Suicide, the Ramones, the Patti Smith Group, and the Heartbreakers, the Voidoids helped define the early New York punk scene.[38]

Upon the album's release, critics such as Velvet Lanier called it "one of the greatest records ever cut"; Jimi LaLumia at The Village Gate called the title track "a classic, a unifying lifeline" for the punk scene;[39] and Record World called it "the Future of American rock".[40] To Joe Ferbacher at Creem, "Blank Generation" was evidence that punk was essentially American, and was more authentic than the more commercially successful but less intellectual or philosophical British punk scene.[41]

Punk became a phenomenon in England, with the quick rise and fall of the Sex Pistols and with longer lasting bands such as the Clash.[38] Glen Matlock was inspired to write "Pretty Vacant" in 1976 after seeing a handbill containing the names of Hell's songs, including "(I Belong To The) Blank Generation", that Malcolm McLaren had brought back to England with him from the United States.[42] Matlock, nor any of the other Pistols, had actually heard Hell's song, as it wasn't released on an album until September 1977. By then, "Pretty Vacant" had already been recorded and released as a single two months earlier. Hell was at first offended at how much McLaren had taken from him—musically, lyrically, and visually—but came to accept it, as he believed "ideas are free property",[43] and praised the band's vocalist Johnny Rotten for taking his nihilist persona further than he felt himself able to do.[44] The Voidoids toured England with the Clash in 1977, and during one show, Rotten appeared on stage and goaded the audience into demanding an encore from Hell and his band.[45] The nihilism of "Blank Generation" was echoed in other songs in the early British punk scene such as the Sex Pistols' "Anarchy in the U.K.", the Clash's "London's Burning" and Generation X's "Your Generation".[46]

Hell became mired in heroin addiction,[38] and the group did not release another album until 1982's Destiny Street, by which time punk had passed from headlines in favor of new wave. The album had a weak reception, and Hell turned focus on non-music projects.[47]

Meanwhile, British punk had swept the US and was to largely define its public perception. American bands influenced by British punk proliferated, and the music evolved into genres such as hardcore punk and alternative rock.[48] Many of these bands delved into punk history and paid tribute to the Voidoids and other New York bands, in particular New York-based noise rockers Sonic Youth, whose frontman Thurston Moore had seen the Voidoids live in the 1970s.[49] The Voidoids were a key influence on the Minutemen, whose D. Boon name-dropped Hell in "History Lesson – Part II".[50]

Track listing

editAll tracks are written by Richard Hell, except as indicated

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Love Comes in Spurts" | 2:03 | |

| 2. | "Liars Beware" | Hell, Ivan Julian | 2:52 |

| 3. | "New Pleasure" | 1:58 | |

| 4. | "Betrayal Takes Two" | Hell, Julian | 3:37 |

| 5. | "Down at the Rock and Roll Club" | 4:05 | |

| 6. | "Who Says?" | 2:07 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Blank Generation" | 2:45 | |

| 2. | "Walking on the Water" | John Fogerty, Tom Fogerty | 2:17 |

| 3. | "The Plan" | 3:56 | |

| 4. | "Another World" | 8:14 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. | "I'm Your Man" | 2:55 | |

| 12. | "All the Way" | Sammy Cahn, Jimmy Van Heusen | 3:22 |

Bonus disc (2017 40th Anniversary Deluxe Edition)

edit- "Love Comes in Spurts" (alternate version from Electric Lady Studios) – 2:01

- "Blank Generation" (alternate version from Electric Lady Studios) – 2:54

- "You Gotta Lose" (alternate version from Electric Lady Studios) – 3:42

- "Who Says?" (alternate version from Plaza Sound Studios) – 2:11

- "Love Comes in Spurts" (live at CBGB, November 19, 1976 – the Voidoids' first public performance) – 2:11

- "Blank Generation" (live at CBGB, November 19, 1976) – 2:41

- "Liars Beware" (live at CBGB, April 14, 1977) – 2:58

- "New Pleasure" (live at CBGB, April 14, 1977) – 2:36

- "Walking on the Water" (live at CBGB, April 14, 1977 – song's live debut for the Voidoids) – 2:11

- "Another World" (original Ork Records EP version) – 6:09

- "Oh" (original 2000 release commissioned by MusicBlitz – final Voidoids recording) – 4:17

- "1977 Sire Records Radio Commercial" – 1:03

- All live CBGB recordings were taken from audience cassette recordings. The "Blank Generation" recording from November 19 cut in halfway through the song's intro. This was repaired by splicing in an intro from another audience cassette recording of "Blank Generation" that was performed the following night. (It happens at 00:19.)

Personnel

editThe Voidoids

edit- Richard Hell – vocals, bass guitar

- Robert Quine – guitar, backing vocals

- Ivan Julian – guitar, backing vocals

- Marc Bell – drums

Technical personnel

edit- Richard Gottehrer – producer

- Richard Hell – producer

- Don Hünerberg, Jerry Solomon, Rob Freeman – engineer

- John Gillespie, Richard Hell – art direction, design

- Roberta Bayley – cover photography

Notes

edit- ^ Quine's admiration of the Velvet Underground led him to make hours of bootleg recordings of the band in 1969, which saw release in 2001 as Bootleg Series Volume 1: The Quine Tapes.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b Hannon 2010, p. 98.

- ^ "It All Began With Richard Hell". Another Magazine. Dazed Media. 7 May 2013.

- ^ André Malraux; Legs McNeil; Gillian McCain (2006). Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk. Grove Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8021-4264-1.

- ^ Hannon 2010, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Hermes 2011, p. 207.

- ^ Astor 2014, p. 45.

- ^ Finney 2012, pp. 24–29.

- ^ Finney 2012, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Finney 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Balls 2014, p. 58.

- ^ Balls 2014, p. 59.

- ^ Astor 2014, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c d Hell, Richard (2017). Blank Generation: 40th Anniversary Deluxe Edition (booklet). Richard Hell and the Voidoids. Rhino Records.

- ^ a b Astor 2014, p. 3.

- ^ Finney 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Astor 2014, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Astor 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Astor 2014, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Astor 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Law 2003, p. 485.

- ^ a b Deming, Mark. "Blank Generation – Richard Hell & the Voidoids / Richard Hell". AllMusic. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ Christgau 1981.

- ^ Fortnam, Ian (January 2018). "Richard Hell and the Voidoids: Blank Generation". Classic Rock. No. 244. Bath. p. 97.

- ^ "Richard Hell & the Voidoids: Blank Generation". Melody Maker. London. 22 February 2000. p. 46.

- ^ Chick, Stevie (February 2018). "Richard Hell & the Voidoids: Blank Generation (40th Anniversary Deluxe Edition)". Mojo. No. 291. p. 105.

- ^ "Richard Hell & the Voidoids: Blank Generation". Q. No. 163. April 2000. pp. 108–11.

- ^ Abowitz 2004, p. 372.

- ^ Norris, Richard (August 1990). "Richard Hell & the Voidoids: Blank Generation". Select. No. 2. p. 119.

- ^ Anderson 1995, p. 180.

- ^ Jones, Allan (February 2018). "Richard Hell & the Voidoids: Blank Generation: 40th Anniversary Deluxe Edition". Uncut. No. 249. pp. 36–38.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (October 31, 1977). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Marsh 1979, p. 168.

- ^ Bangs 1983, p. 222.

- ^ Grant, Steven; Fleischmann, Mark; Sprague, Deborah; Robbins, Ira. "Richard Hell & the Voidoids". Trouser Press. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Ratliff, Ben (August 31, 2009). "CRITICS' CHOICE: New CDs". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Sid (April 24, 2007). "Review of Richard Hell and the Voidoids – Blank Generation". BBC Music. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (October 18, 2017). "Richard Hell and the Voidoids Prep 'Blank Generation' Reissue". Rolling Stone. New York. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Finney 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Ross Finney (April 10, 2012). "A Blank Generation: Richard Hell and American Punk Rock" (PDF). Americanstudies.nd.edu. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ Finney 2012, p. 35.

- ^ Finney 2012, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Matlock 2012, p. 103.

- ^ Finney 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Finney 2012, p. 53.

- ^ Finney 2012, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Finney 2012, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Finney 2012, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Finney 2012, pp. 57–61.

- ^ Finney 2012, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Finney 2012, pp. 63.

Works cited

edit- Abowitz, Richard (2004). "Richard Hell". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Anderson, Steve (1995). "Richard Hell & the Voidoids". In Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig (eds.). Spin Alternative Record Guide. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.

- Astor, Pete (2014). Richard Hell and the Voidoids' Blank Generation. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62356-856-6.

- Balls, Richard (2014). Be Stiff: The Stiff Records Story. Soundcheck Books. ISBN 978-0-9575700-6-1.

- Bangs, Lester (1983). "Richard Hell and the Voidoids". In Marsh, Dave; Swenson, John (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Record Guide (2nd ed.). Random House/Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 0-394-72107-1.

- Christgau, Robert (1981). "H". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor and Fields. ISBN 0-89919-026-X. Retrieved February 26, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- Finney, Ross (April 10, 2012). A Blank Generation: Richard Hell and American Punk Rock (PDF) (Senior thesis). University of Notre Dame. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- Hannon, Sharon M. (2010). Punks: A Guide to an American Subculture. ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-0-313-36456-3.

- Hermes, Will (2011). Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-1-4299-6867-6.

- Law, Glenn (2003). "Richard Hell". In Buckley, Peter (ed.). The Rough Guide to Rock. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-105-0.

- Marsh, Dave (1979). "Richard Hell and the Voidoids". In Marsh, Dave; Swenson, John (eds.). The Rolling Stone Record Guide (1st ed.). Random House/Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 0-394-73535-8.

- Matlock, Glen (2012). I Was a Teenage Sex Pistol (2nd ed.). Rocket 88. ISBN 978-1-906615-36-9.

External links

edit- Blank Generation at Discogs (list of releases)