Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War.[1] In particular, the term referred to men enslaved by Patriots who served on the Loyalist side because of the Crown's guarantee of freedom.

| Black Loyalist | |

|---|---|

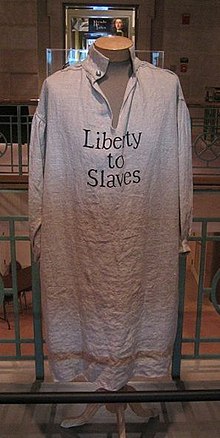

Smock similar to those worn by Black Loyalist soldiers in Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment | |

| Active | 1775–1784 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | British provincial units, Loyalist militias, associators |

| Type | infantry, dragoons (mounted infantry), irregular, labor duty |

| Size | companies-regiments |

| Engagements | American Revolutionary War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Both White British military officers and Black Loyalist officers |

Some 3,000 Black Loyalists were evacuated from New York to Nova Scotia; they were individually listed in the Book of Negroes as the British gave them certificates of freedom and arranged for their transportation.[2] The Crown gave them land grants and supplies to help them resettle in Nova Scotia. Some of the European Loyalists who emigrated to Nova Scotia brought their enslaved servants with them, making for an uneasy society. One historian has argued that those enslaved people should not be regarded as Loyalists, as they had no choice in their fates.[3] Other Black Loyalists were evacuated to London or the Caribbean colonies.

Thousands of enslaved people escaped from plantations and fled to British lines, especially after the British occupation of Charleston, South Carolina. When the British evacuated, they took many with them. Many ended up among London's Black Poor, with 4,000 resettled by the Sierra Leone Company to Freetown in Africa in 1787. Five years later, another 1,192 Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia chose to emigrate to Sierra Leone, becoming known as the Nova Scotian Settlers in the new British colony of Sierra Leone. Both waves of settlers became part of the Sierra Leone Creole people and the founders of the nation of Sierra Leone. Thomas Jefferson referred to the Black Loyalists as "the fugitives from these States".[4]

Background

editLegal statutes had never authorized slavery in England. Villeinage, a form of semi-serfdom, was legally recognized but long obsolete. In 1772, an enslaved person threatened with being taken out of England and returned to the Caribbean challenged the authority of his enslaver in the case of Somerset v Stewart. The Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield, ruled that slavery had no standing under common law and enslavers, therefore, were not permitted to transport enslaved people outside England and Wales against their will. Many observers took it to mean that slavery was ended in England.

Lower courts often interpreted the ruling as determining that the status of slavery did not exist in England and Wales, but Mansfield ruled more narrowly. The decision did not apply to the North American and Caribbean colonies, where local legislatures had passed laws to institutionalize slavery. Many cases were presented to the English courts for the emancipation of enslaved people residing in England, and numerous American runaways hoped to reach England, where they expected to gain freedom.

Enslaved Americans began to believe that King George III was for them and against their enslavers as tensions increased before the American Revolution. Colonial enslavers feared a British-inspired slave rebellion, and Lord Dunmore wrote to Lord Dartmouth in early 1775 of his intention to take advantage of the situation.[5]

Proclamations

editDunmore's Proclamation

editIn November 1775, Lord Dunmore issued a controversial proclamation. As Virginia's royal governor, he called on all able-bodied men to assist him in the defence of the colony, including enslaved people belonging to the Patriots. He promised such enslaved recruits freedom in exchange for service in the British Army:

I do require every Person capable of bearing Arms, to resort to His MAJESTY'S STANDARD, or be looked upon as Traitors to His MAJESTY'S Crown and Government, and thereby become liable to the Penalty the Law inflicts upon such Offences; such as forfeiture of Life, confiscation of Lands, &c. &c. And I do hereby further declare all indented Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His MAJESTY'S Troops as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this Colony to a proper Sense of their Duty, to His MAJESTY'S Crown and Dignity.

— Lord Dunmore's Proclamation, November 7, 1775[6]

Within a month, about 800 enslaved or formerly enslaved people had fled to Norfolk, Virginia, to enlist.[7][8] Outraged Virginia enslavers decreed that those fleeing eslavement would be executed. They also counteracted the promises of Lord Dunmore by claiming that those who escaped to Lord Dunmore would be sold to sugar plantations in the Caribbean. However, many enslaved people were willing to risk their lives for a chance at freedom.[9]

Lord Dunmore's Proclamation was the first mass emancipation of enslaved people in America.[7] The 1776 Declaration of Independence refers obliquely to the proclamation by citing it as one of its grievances, that King George III had "excited domestic Insurrections among us".[10] An earlier version of the Declaration was more explicit, stating the following of King George III, but these controversial details were dropped during the final development of the document in Congress:

He is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people on whom he has obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed again the Liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

— Draft Declaration of Independence, 1776[11]

Jamaican Governor John Dalling drafted a proposal in 1779 for the enlistment of a regiment of mulattoes and another regiment of free Negroes.[12]

Philipsburg Proclamation

editWith the arrival of 30,000 Hessian mercenary troops, the British did not have as much need for the formerly enslaved. Sir William Howe banned the formation of new Black regiments and disbanded his own. But freeing those enslaved by rebels still held value as economic warfare against the American so-called Patriots. In 1779, Sir Henry Clinton issued the Philipsburg Proclamation, expanding Dunmore's Proclamation and promising freedom to any person enslaved by a Patriot.[13] However, Clinton often ordered the returned escaped enslaved people to Loyalist enslavers, though he requested the owner to refrain from punishment. In 1778, the Patriots promised freedom to those enslaved by Loyalists. But as Boston King noted in his memoir, both Patriots and Loyalists who captured escaped enslaved people often sold them back into slavery.[13]

Evacuation and resettlement

editWhen the British evacuated their troops from Charleston and New York after the war, they made good on their promises and took thousands of freed people with them. They resettled the freedmen in colonies in the Caribbean, such as Jamaica, and in Nova Scotia and Upper Canada, as well as transporting some to London. The Canadian climate and other factors made Nova Scotia difficult. In addition, the Poor Blacks of London, many freed people, had trouble getting work. British abolitionists ultimately founded Freetown in what became Sierra Leone on the coast of West Africa as a place to resettle Black Loyalists from London and Canada and Jamaican Maroons. Nearly 2,000 Black Loyalists left Nova Scotia to help found the new African colony. Their descendants are the Sierra Leone Creole people.[14][15][16][17]

Black Loyalist military units

editLord Dunmore's proclamation and others led to the formation of several Black regiments in the British army. The most notable were Dunmore's Royal Ethiopian Regiment and Clinton's Black Company of Pioneers. Other regiments included the Jersey Shore Volunteers, the Jamaica Rangers, the Mosquito Shore Volunteers, and the Black Dragoons of the South Carolina Royalists. It was also common for Black Loyalists to serve the military in non-combat positions, such as the Black Company of Pioneers.[18][19]

Royal Ethiopian Regiment

editLord Dunmore organized 800 Black Loyalist volunteers into the Royal Ethiopian Regiment. They trained in the rudiments of marching and shooting before engaging in their first conflict at the Battle of Kemp's Landing. The Patriot militia at Kemp's Landing was unprepared for the attack and retreated. Next, Dunmore led the Royal Ethiopians into the Battle of Great Bridge; Dunmore was overconfident and misinformed about the Patriot numbers; however, the Patriots overwhelmed the British troops. After the battle, Dunmore loaded his Black troops onto ships of the British fleet, hoping to take the opportunity to train them better. The cramped conditions led to the spread of smallpox. By the time Dunmore retreated to the Province of New York, only 300 of the original 800 soldiers had survived.[18]

Black Company of Pioneers

editThe largest Black Loyalist regiment was the Black Company of Pioneers, better known as the "Black Pioneers" and later merged into the Guides and Pioneers. In the military terminology of the day, a "pioneer" was a soldier who built roads, dug trenches, and did other manual labor. These soldiers were typically divided into smaller corps and attached to larger armies. The Black Pioneers worked to build fortifications and other necessities, and they could be called upon to work under fire.[19] They served under General Clinton in a support capacity in North Carolina, New York, Newport, Rhode Island, and Philadelphia. They did not sustain any casualties because they were never used in combat. In Philadelphia, their general orders were to "attend the scavengers, assist in cleaning the streets & removing all newsiances being thrown into the streets".[20]

Black Brigade

editThe "Black Brigade" was a small combat unit of 24 in New Jersey led by Colonel Tye, a former slave from Monmouth County, New Jersey who had escaped to British lines early in the war.[21] The title of colonel was not an official military designation, as he was not formally commissioned as an officer. Still, such titles were permitted anyway in an unofficial capacity. Tye and the Black Brigade were the most feared Loyalists in New Jersey, and he led them in several raids from 1778 at the Battle of Monmouth to defending the British in occupied New York in the winter of 1779. Beginning in June 1780, Tye led several actions against Patriots in Monmouth County, and he was wounded in the wrist during a raid on a Patriot militia leader in September. Within weeks, he died from gangrene,[19] and Black Pioneer leader Stephen Blucke took over the Black Brigade and led it through the end of the war.[21]

Postwar treatment

editWhen peace negotiations began after the siege of Yorktown, a primary issue of debate was the fate of Black British soldiers. Loyalists who remained in the United States wanted Black soldiers returned so their chances of receiving reparations for the damaged property would be increased, but British military leaders fully intended to keep the promise of freedom made to Black soldiers despite the anger of the Americans.[22]

In the chaos as the British evacuated Loyalist refugees, mainly from New York and Charleston, American enslavers attempted to enslave and re-enslave many people. Some would kidnap any Black person, including those born free before the war, and enslave them.[23] The U.S. Congress ordered George Washington to retrieve any American property, including enslaved people, from the British, as stipulated by the Treaty of Paris of 1783.

Since Lieutenant General Guy Carleton intended to honor the promise of freedom, the British proposed a compromise that would compensate enslavers and provide certificates of freedom and the right to be evacuated to one of the British colonies to any Black person who could prove his service or status. The British transported more than 3,000 Black Loyalists to Nova Scotia, the greatest number of people of African descent to arrive there at any one time. One of their settlements, Birchtown, Nova Scotia was the largest free African community in North America for the first few years of its existence.[24]

Black Loyalists found the northern climate and frontier conditions in Nova Scotia difficult and were subject to discrimination by other Loyalist settlers, many of them enslavers. In July 1784, Black Loyalists in Shelburne were targeted in the Shelburne Riots, the first recorded race riots in Canadian history. Crown officials granted lesser quality lands to the Black Loyalists, which were more rocky and less fertile than those given to White Loyalists. In 1792, the British government offered Black Loyalists the chance to resettle in a new colony in Sierra Leone. The Sierra Leone Company was established to manage its development. Half of the Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia, nearly 1200, departed the country and moved permanently to Sierra Leone. They set up the community of "Freetown".[25]

In 1793, the British transported another 3,000 Blacks to Florida, Nova Scotia, and England as free men and women.[26] Their names were recorded in the Book of Negroes by Sir Carleton.[27][28]

Approximately 300 free Black people in Savannah refused to evacuate at the end of the war, fearing they would be re-enslaved once they arrived in the West Indies. They established an independent colony in swamps near Savannah River, though by 1786, most of them were discovered and re-enslaved, as Southern planters ignored the fact that the British had freed them during the war. When the British ceded the colonies of East Florida and West Florida back to Spain per the terms of the Treaty of Paris, hundreds of free Black people who had been transported there from the South were left behind as British forces pulled out of the region.[29]

Descendants

editMany descendants of Black loyalists have been able to track their ancestry by using General Carleton's Book of Negroes.[30] The number of these descendants is unknown.[31]

Nova Scotia

editBetween 1776 and 1785, around 3,500 Blacks were transported to Nova Scotia from the United States, part of a more extensive migration of about 34,000 Loyalist refugees. This massive influx of people increased the population by almost 60% and led to the establishment of New Brunswick as a colony in 1784. Most of the free Blacks settled at Birchtown, the most prominent Black township in North America at the time, next to the town of Shelburne, settled by Whites.[32] There are also several Black loyalists buried in unmarked graves in the Old Burying Ground (Halifax, Nova Scotia).

Among the descendants of the Black Loyalists are noted figures such as Rose Fortune, a Black woman living in Nova Scotia who became a police officer and a businesswoman.[33] Measha Brueggergosman (née Gosman), the Canadian opera and concert singer, is a New Brunswick native and descendant of a Black Loyalist through her father. In the closing days of the Revolution, along with British troops and other Black Loyalists, her paternal four-times-great-grandfather and grandmother left the colonies. They were resettled in Shelburne with their first child, born free behind British lines in New York.

Commemoration

editThe Black Loyalist settlement of Birchtown, Nova Scotia was declared a National Historic Site in 1997. A seasonal museum commemorating the Black Loyalists was opened in that year by the Black Loyalist Heritage Society. A memorial has been established at the Black Loyalist Burying Ground. Built around the historic Birchtown school and church, the museum was badly damaged by an arson attack in 2008 but rebuilt. The Society began plans for a major expansion of the museum to tell the story of the Black Loyalists in America, Nova Scotia, and Sierra Leone.[34]

Sierra Leone

editSome Black Loyalists were transported to London, where they struggled to create new lives. Sympathy for the black veterans who had fought for the British stimulated support for the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. This organization backed the resettlement of the black poor from London to a new British colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa. In addition, Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia were offered the opportunity to relocate, and about half chose to move to the new colony. Today, the descendants of these pioneers are known as the Sierra Leone Creole people, or Krios. They live primarily in the Western Area of Freetown.

Black Loyalists from the American South brought their languages to Freetown, such as Gullah[citation needed] from the Low Country and African American Vernacular English. Their lingua franca was a strong influence on the descendants of this community, who developed Krio as a language. Many Sierra Leone Creoles or Krios can trace their ancestry directly to their Black Loyalist ancestors.

An example of such an ancestor is Harry Washington, likely born about 1740 in The Gambia, enslaved as a young man and shipped to Virginia.[36] He was purchased by George Washington in 1763; he escaped about 1776 in Virginia to British lines, eventually making his way to New York.[37] He was among free blacks evacuated to Nova Scotia by the British following the war.[37][38] He later took the opportunity to migrate to Freetown in Africa. By 1800, he became the leader of a rebellion against colonial rule and faced a military tribunal.[36] His descendants are part of the Creole population, who make up 5.8% of the total.

Notable people

edit- Stephen Blucke, commanding officer of the Black Company of Pioneers

- David George, American Baptist preacher

- Abraham Hazeley, Nova Scotian settler

- Boston King, first Methodist missionary to Indigenous Africans

- Moses Wilkinson, American Methodist preacher

- John Kizell, an American immigrant to Sierra Leone

- John Marrant, Methodist preacher

- Cato Perkins, American missionary to Sierra Leone

- Thomas Peters, one of the "Founding Fathers" of the nation of Sierra Leone

- Colonel Tye, soldier

- Harry Washington, a freedman who resettled in Sierra Leone after enslavement to George Washington

In popular culture

edit- The saga of the Black Loyalists inspired Lawrence Hill's 2007 novel The Book of Negroes (published as Someone Knows My Name in the United States). It won the 2008 Commonwealth Award for Fiction.

- In the second episode of the 2016 miniseries Roots, protagonist Kunta Kinte is a Black Loyalist and briefly serves in Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment.

See also

edit- Black Patriot, an African American who fought for the Patriots during the American Revolution

- Black refugee (War of 1812)

- Black Nova Scotians

- History of Nova Scotia

- Birchtown, Nova Scotia

- Billy (slave)

References

edit- ^ Cassandra Pybus, Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and Their Global Quest for Liberty, (Beacon Press, Boston, 2006); Graham Russell Hodges, Susan Hawkes Cook, Alan Edward Brown (eds), The Black Loyalist Directory: African Americans in Exile After the American Revolution (subscription required)

- ^ The Book of Negroes Archived 2022-07-30 at the Wayback Machine, Black Loyalists.

- ^ Barry Cahill, "The Black Loyalist Myth in Atlantic Canada", Acadiensis, University of New Brunswick

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (1900). The Jeffersonian Cyclopedia. Funk & Wagnalls Company. p. 621 (#5808). Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- ^ Selig, Robert A. "The Revolution's Black Soldiers". AmericanRevolution.org. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ "Lord Dunmore's Proclamation". Digital History. 2007-10-18. Archived from the original on 2008-04-22. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ a b "Lord Dunmore's Proclamation". Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People. Canada's Digital Collection. Archived from the original on 2007-11-16. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ^ Jack Phillip Greene, Jack Richon Pole (2000). A Companion to the American Revolution. Blackwell Publishing. p. 241. ISBN 0-631-21058-X. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ "Escape from Slavery". Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People. Canada's Digital Collection. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ^ Kaplan, Sidney (July 1976). "The "Domestic Insurrections" of the Declaration of Independence". Journal of Negro History (PDF). 61 (3): 243–255. doi:10.2307/2717252. JSTOR 00222992. S2CID 149796469. [dead link]

- ^ "(1776) The Deleted Passage of the Declaration of Independence". Blackpast.org. 10 August 2009. Retrieved 2019-11-24.

- ^ Dalling, John (May 25, 1779). "Black Loyalists Proposed Corps". Loyalist Institute. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ a b "The Philipsburg Proclamation". Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People. Canada's Digital Collection. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ^ Thayer, James Steel (1991). A Dissenting View of Creole Culture in Sierra Leone. pp. 215–230. https://www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1991_num_31_121_2116

- ^ Browne-Davies, Nigel (2014). A Precis of Sources relating to genealogical research on the Sierra Leone Krio people. Journal of Sierra Leone Studies, Vol. 3; Edition 1, 2014 https://www.academia.edu/40720522/A_Precis_of_Sources_relating_to_genealogical_research_on_the_Sierra_Leone_Krio_people

- ^ Walker, James W (1992). "Chapter Five: Foundation of Sierra Leone". The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 94–114. ISBN 978-0-8020-7402-7., originally published by Longman & Dalhousie University Press (1976).

- ^ Taylor, Bankole Kamara (February 2014). Sierra Leone: The Land, Its People and History. New Africa Press. p. 68. ISBN 9789987160389.

- ^ a b "The Royal Ethiopian". Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People. Canada's Digital Collection. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ^ a b c "The Black Pioneers". Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People. Canada's Digital Collection. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ Nan Cole and Todd Braisted (February 2, 2001). "A History of the Black Pioneers". Loyalist Institute.

- ^ a b Jonathan D. Sutherland, African Americans at War, ABC-CLIO, 2003, pp. 420–421, accessed 4 May 2010

- ^ "The Treaty of Paris". Black Loyalists: Our People, Our History. Canada's Digital Collections. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ "Chaos in New York". Black Loyalists: Our People, Our History. Canada's Digital Collections. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ "Who were the Black Loyalists?". Remembering Black Loyalists, Black Communities in Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia Museum. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ Walker, James W. (1992). "Chapter Five: Foundation of Sierra Leone". The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 94–114. ISBN 978-0-8020-7402-7. Originally published by Longman & Dalhousie University Press (1976).

- ^ Among them was Deborah Squash, a 20-year-old woman who had escaped from George Washington's plantation in 1779. She is described in the Book of Negroes as a "stout wench, thick lips, pock marked. Formerly slave to General Washington, came away about 4 years ago." "Life Stories: Profiles of Black New Yorkers During Slavery and Emancipation" (PDF). Slavery in New York. New-York Historical Society. 2005. p. 103. Retrieved 2007-10-19."Book of Negroes". Black Loyalists: Our People, Our History. Canada's Digital Collections. 1783. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ "Certificates of Freedom". Black Loyalists: Our People, Our History. Canada's Digital Collections. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ "The Book of Negroes". Africans in America: Revolution. PBS. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ "Returned to Slavery". Black Loyalists: Our People, Our History. Canada's Digital Collections. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ Sege, Irene (February 21, 2007). "The search: Interest in piecing together family trees grows among African-Americans". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ "Canada makes amends to descendants of black loyalists". The Economist. 30 September 2017.

- ^ "Black Loyalist Communities in Nova Scotia". Remembering Black Loyalists, Black Communities in Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia Museum. Archived from the original on 2007-11-11. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ "Rose Fortune, a special Canadian!". African American Registry. 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ Black Loyalist Heritage Society website

- ^ Canadian Biography Also see Hartshorne's portrait by Robert Field (painter)

- ^ a b Pybus, Cassandra (2006). "Washington's Revolution". Atlantic Studies. 3 (2): 183–199. doi:10.1080/14788810600875414. S2CID 159201709.

- ^ a b Lepore, Jill (8 May 2006). "Goodbye, Columbus: When America won its independence, what became of the slaves who fled for theirs?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ Black Loyalist website.

Further reading

edit- Cahill, Barry. "The Black Loyalist Myth in Atlantic Canada," Acadiensis 29, no. 1 (Autumn 1999), 76-87.

- Gilbert, Alan. Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2012. ISBN 978-0-226-10155-2

- Holman, James, Travels in Madeira, Sierra Leone, Teneriffe, St. Jago, Cape Coast, Fernando Po, Princes Island, etc. (Google eBook), 1840

- Pulis, John W. ed. Moving On: Black Loyalists in the Afro-Atlantic World. New York: Garland 1999.

- Pybus, Cassandra. Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and Their Global Quest for Liberty, New York: Beacon, 2006

- Schama, Simon, Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution (London: BBC Books, 2005) (New York: Ecco, 2006)

- Walker, James W. St. G. "Myth, History, and Revisionism: The Black Loyalists Revised," Acadiensis 29, No. 1 (Autumn 1999), 881-105.

External links

edit- Black Loyalist website

- "Biographies of the Loyalist Era: Thomas Peters, Black Loyalist", The Loyalists, Learn Quebec

- "Loyalties" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, University of Manitoba, Vol. 17, No. 1

- Heritage: Black Loyalists, Saint John

- Black Loyalist Heritage Society, official website

- Black History, National Archives, United Kingdom

- Africans in America: Revolution, PBS

- Loyalist Institute, Documents and writings on Black Loyalists

- Anti-Slavery movement, Collections Canada

- Enslaved Africans in Upper Canada, Archives

- Nova Scotia archives, virtual exhibition Archived 2013-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Black Loyalists' experience in Canada, Atlantic Canadian Portal