49°37′56″N 8°21′36″E / 49.6323°N 8.3601°E

The Bischofshof palace (German: Schloss Bischofshof or English: Bishop's Court or English: Bishop's Palace) was a former Baroque-style palace in Worms, Germany. It was located next to the Worms Cathedral, on its northern side, on the current Schlossplatz (English: Palace Square)). It served as the main residence of the prince-bishops of Worms.

In the Middle Ages, the first palace was originally constructed as a Kaiserpfalz, a temporary seat of the Holy Roman Emperor. This building became later the court of the prince-bishop of Worms. It was destroyed during the Nine Years' War in 1689. Between 1719 and 1725, it was rebuilt as a baroque-style palace with involvement of the architect Balthasar Neumann. It was elongated structure with side wings, featuring a central Avant-corps facing the palace square. During the French Revolutionary Wars, the episcopal palace was destroyed in 1794.

In the 19th century, a patrician built the so-called Heyl-Schlösschen, which remains till today. From the Bischofshof palace nothing remains except a vaulted cellar in the Heyl garden.

History

editMiddle Ages

editThe medieval royal palace in Worms was located immediately north of the cathedral. Initially, it was used a temporary residence of the Holy Roman Emperor, a so-called Kaiserpfalz. From the late Middle Ages onwards, it was used by the prince-bishops as a city residence.

The Bischofshof palace was situated within the cathedral immunity (German: Domfreiheit)) area. The complex consisted of a series of buildings that had been constructed sequentially. Also, it had its own access to the cathedral through its north nave. And in addition, the palace featured its own church in the northern part of the palace complex, the former palace chapel, St. Stephen.

The hall of the palace was renovated in the 16th century —perhaps for the Diet of Worms in 1521. It is believed that Martin Luther (1483–1546) stood here before emperor Charles V (1500–1558), when he was summoned in order to renounce or reaffirm his views in response to a Papal bull of Pope Leo X. In answer to questioning, he defended these views and refused to recant them. At the end of the diet, the Emperor issued the Edict of Worms (Wormser Edikt), a decree which condemned Luther as "a notorious heretic" and banned citizens of the Empire from propagating his ideas. Although the Protestant Reformation is usually considered to have begun in 1517, the edict signals the first overt schism. At this site, now part of the Heyl Garden—there, is a monument named Die Großen Schuhe Luthers (Luther's large shoes) and a modern informational pillar to commemorate the event.

The medieval complex was destroyed by French troops in 1689 during the Nine Years' War.[1]

Baroque palace

editIn 1719, prince-bishop Francis Louis of Palatinate-Neuburg (1664–1732) decided to reconstruct the Bischofshof palace.[2] The construction site was moved as far west as possible within the area, up to the medieval city wall. However, the gained forecourt was still very limited, providing barely enough space for a representative driveway.[3]

The shell of the building was completed in 1725, and by 1732 the new Bischofshof palace was at least partially usable. However, this complex was heavily damaged again in 1735 by French troops during the War of the Polish Succession.[4] Meanwhile, Franz Georg von Schönborn (1682–1756) had become bishop of Worms. His brother, Johann Philipp Franz von Schönborn (1673–1724), prince-bishop of Würzburg, had the experienced architect Balthasar Neumann (1687–1753) under contract, whom Franz Georg borrowed. From 1738, Neumann repeatedly worked on the reconstruction of the Bischofshof palace, which was completed in 1744.[3] Jacob Michael Küchel also participated in the reconstruction.[5]

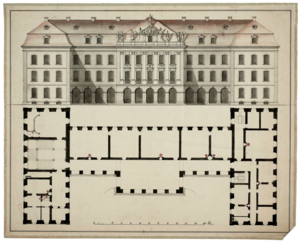

The resulting baroque-style Bischofshof palace was a broad, three-story building in an H-shape. It served both as a residential palace and an administrative building. The eastern front was accented by a five-axis central Avant-corps.[3] The building featured a powerful mansard roof.[6]

A large hall, extending over the first and second floors of the central Avant-corps and half the depth of the building, formed the centrepiece of the complex.[7] The bishop's chapel occupied the southwest corner and also extended over two floors, starting from the ground floor.[7] The staircase was located in the western part of the building.[8] The bishop's representative and living quarters were on the first floor, facing west, spanning the entire width of the building.[9]

From 1740, there were ideas to expand the complex. However, the existing plans, attributed to Balthasar Neumann, were not implemented.

French Revolutionary Wars

editIn 1791, the Bischofshof Palace temporarily served as a refuge for Louise Joseph, prince of Condé, (1736–1818) during his exile.[10]

On 20 January 1794, French Revolutionary troops burned down the palace.[11] The downfall of the prince-bishopric of Worms in 1801 rendered a reconstruction unnecessary.

19th and 20th century: Heyl-Schlösschen and Heylshof

editIn 1805, Cornelius Heyl acquired the site but sold parts of it. He retained the central area with the ruins of the bishop's court and sold the demolition material. Subsequently, this area was also used as a garden.[12] After 1851, he repurchased the northern part of his property, on which a residential house had meanwhile been built.

In 1867, on the occasion of Cornelius Wilhelm von Heyl zu Herrnsheim's marriage to Sophie Stein, daughter of a Cologne banker, it was modernized and expanded into a prestigious city palace, henceforth referred to as "Heyl-Schlösschen".[13] Severely damaged in the Second World War, it was rebuilt in a much-reduced form afterwards.

In the 1860s, the committee for the erection of a Luther Monument cast covetous eyes on the property, as it was considered an authentic site of the 1521 event.[14] However, the Heyl family refused to sell their property.[15]

From 1881, Heyl, whose family had grown to five children, built a large new building on the northern edge of the area, the "Heylshof". This building, too, was heavily damaged in World War II and was only rebuilt in a reduced form as well.[16]

Modern Times

editToday, little remains of the original Bischofshof palace. The two houses built by the Heyl family are still there, although rebuilt in reduced form. The Heylshof houses a museum and can be visited, while the Heyl-Schlösschen is still lived in by the family.

In the Heyl garden, a vaulted cellar of the baroque palace is preserved.[17] It measures 43 × 7.67 meters with a vault height of 4.66 meters. It lies beneath several meters of rubble.[18]

References

edit- ^ Werner: Die vergessene Residenz, S. 127.

- ^ Werner: Die vergessene Residenz, S. 128.

- ^ a b c Werner: Die vergessene Residenz, S. 130.

- ^ Werner: Die vergessene Residenz, S. 129.

- ^ Werner: Die vergessene Residenz, S. 130f.

- ^ Werner: Die vergessene Residenz, S. 131.

- ^ a b Werner: Die vergessene Residenz, S. 132.

- ^ Werner: Die vergessene Residenz, S. 133.

- ^ Werner: Die vergessene Residenz, S. 135ff.

- ^ Kranzbühler, Eugen (1905). "Der Bischofshof". Verschwundene Wormser Bauten: Beiträge zur Baugeschichte und Topographie der Stadt (in German). Worms: Wernerscher Verlag. p. 133.

- ^ Kranzbühler, Eugen (1905). "Der Bischofshof". Verschwundene Wormser Bauten: Beiträge zur Baugeschichte und Topographie der Stadt (in German). Worms: Wernerscher Verlag. p. 134.

- ^ Werner: Von Wohnhäusern, S. 192.

- ^ Werner: Von Wohnhäusern, S. 195.

- ^ Werner: Das Lutherdenkmal, S. 227.

- ^ Werner: Das Lutherdenkmal, S. 228–230.

- ^ Werner: Von Wohnhäusern, S. 201ff.

- ^ Werner: Die vergessene Residenz, S. 137ff.

- ^ Susanne Müller: Auf der Suche nach Gewölbe. In: Wormser Zeitung vom 28. Februar 2019, S. 9.

Literature

edit- Kranzbühler, Eugen (1905). "Der Bischofshof". Verschwundene Wormser Bauten: Beiträge zur Baugeschichte und Topographie der Stadt (in German). Worms: Wernerscher Verlag. pp. 118–136.

- Illert, Friedrich Maria (1958). "Kaiserpfalz und Bischofshof in Worms". Der Wormsgau (in German). 3: 136–148.

- Werner, Ferdinand (2007). "Die vergessene Residenz. Balthasar Neumann, Jacob Michael Küchel und der Wormser Bischofshof". In Dittmann, Lorenz (ed.). Sprachen der Kunst - Festschrift für Klaus Güthlein zum 65. Geburtstag (in German). Worms: Wernerscher Verlag. pp. 127–138. ISBN 978-3923532131.

- Werner, Ferdinand (2010). "Von Wohnhäusern, Landsitzen und Villen". In Bönnen, Gerold (ed.). Die Wormser Industriellenfamilie von Heyl. Öffentliches und privates Wirken zwischen Bürgertum und Adel (in German). Worms: Wernerscher Verlag. pp. 187–312. ISBN 978-3-88462-304-6.

- Werner, Ferdinand (2012). "Das Lutherdenkmal und die Wormser Grünanlagen". Die Gartenkunst (in German). 2: 223–259.

External links

edit- "Bishop's palace (part of the Luther Tour including 3-D rendering of the medieval palace)". www.worms.de. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- "Museum Heylshof Stiftung Kunsthaus Heylshof in Worms". www.heylshof.de/ (in German). Retrieved 17 May 2024.

Gallery: Details from the 18th century baroque Bischofshof palace

edit-

Floor plan of the baroque-style Bischofshof palace

-

Intersection of the palace staircase and chapel (Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz)

-

Intersection of the baroque-style Bischofshof palace (Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz)

-

The baroque-style Bischofshof palace (Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz)