Bernard Pivot (French: [bɛʁnaʁ pivo]; 5 May 1935 – 6 May 2024) was a French journalist, interviewer and host of cultural television programmes. He was chairman of the Académie Goncourt from 2014 to 2020.[1][2][3]

Bernard Pivot | |

|---|---|

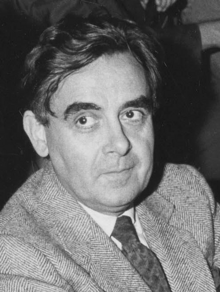

Pivot in 1986 | |

| Born | Bernard Claude Pivot 5 May 1935 Lyon, France |

| Died | 6 May 2024 (aged 89) Neuilly-sur-Seine, France |

| Education | Lycée Ampère |

| Alma mater | University of Lyon Centre de formation des journalistes |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, television personality |

| Known for | TV host Apostrophes and Bouillon de culture |

Biography

editPivot was born in Lyon on 5 May 1935,[citation needed] the son of two grocers. During World War II his father, Charles Pivot, was taken prisoner and his mother moved the family home to the village of Quincié-en-Beaujolais, where Bernard Pivot started school. In 1945 his father was released and the reunited family returned to Lyon. At age 10 Pivot went to a Catholic boarding school where he discovered a passion for sport, while he was more average at traditional school subjects, except French and history.[citation needed]

After starting law studies in Lyon Pivot entered the Centre de formation des journalistes (CFJ) in Paris, where he met his future wife, Monique.[citation needed] He graduated second in his class. After an internship at Le Progrès in Lyon, he studied economic journalism for a full year, and then joined the Figaro Littéraire in 1958.[citation needed]

In 1970 he hosted a humorous daily radio programme . In 1971 the Figaro Littéraire closed and Pivot joined Le Figaro. He left in 1974 after a disagreement with Jean d'Ormesson. Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber invited him to start a new project, which led to the creation of a new magazine, Lire, a year later. Meanwhile, he had begun hosting a television programme in April 1973 called Ouvrez les guillemets on the First Channel of the ORTF. In 1974, the ORTF was dissolved and Pivot started his Apostrophes programme. Apostrophes was first broadcast on Antenne 2 on 10 January 1975, and ran until 1990.[4][5] Pivot then created Bouillon de culture, with the aim of broadening people's interests beyond reading. However, he eventually returned to books.[6]

Pivot died of cancer in Neuilly-sur-Seine, on 6 May 2024, at the age of 89.[7]

Spelling championships

editIn 1985, Pivot created the Championnats d'orthographe ("Spelling Championships") with linguist Micheline Sommant,[8] which in 1992 became Championnats mondiaux d'orthographe ("World Spelling Championships"), then the Dicos d'or ("Golden Dictionaries") in 1993.[citation needed]

Pivot and James Lipton

editJames Lipton was inspired to create Inside the Actors Studio by a chance viewing of a Pivot programme on cable TV. Lipton adapted Pivot's use of a Proust Questionnaire to one that he himself used at the end of each episode of Inside the Actors Studio.[9]

However, the question "If God exists, what would you like Him to tell you when you're dead?" was considered potentially offensive to US audiences and replaced by a more acceptable "If heaven exists, what would you like to hear God say when you arrive at the pearly gates?"[citation needed]

Pivot became aware that Lipton was inspired by his questionnaire and invited him to appear on the final episode of Bouillon de culture.[10]

Television work

edit- Ouvrez les guillemets (1973–1974)[11]

- Apostrophes (1975–1990)[11]

- Bouillon de culture (1991–2001)[11]

- Double je (2002–2006)[11]

Defence of paedophilia

editOn 26 November 1973, Pivot invited the paedophile novelist Tony Duvert onto his show Ouvrez les guillemets. Duvert refused, letting his editor and supporters Jérôme Lindon and Alain Robbe-Grillet promote his book.[12]

In January 1975, Yves Berger, the literary director of Éditions Grasset and Pierre Sabbagh's cultural adviser on the 2nd channel of French television, persuaded Jacqueline Baudrier, in charge of the 1st channel, to replace Marc Gilbert's Italics with Pivot's Ouvrez les guillemets talk show.[13] On 30 May 1975, he received Vladimir Nabokov, the author of Lolita on Apostrophes; on 12 December 1976, Michel Foucault, who criticised psychoanalysis and "contractual sexuality" based on consent or non-consent, with René Schérer, Guy Hocquenghem and François Châtelet; on 14 October 1983, Renaud Camus, defender of the paedophile cause;[14] on 23 April 1982, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, who described having ambiguous relations with children in kindergarten;[15] on 2 March 1990, Gabriel Matzneff, a noted paedophile[16] whose book Mes amours décomposés was highly criticised;[17] on 23 February 2001, Catherine Dolto, to talk about the legalisation of paedophilia on Bouillon de Culture; and in 2005, Michel Tournier, whose references to paedophilia were published in La Pléiade in 2017.[18]

On 17 March 2013, Pivot defended Alexandre Postel's book Un homme effacé, which described a man who owns explicit pictures of children on his computer,[19] and on 30 October 2016, La Mauvaise vie by Frédéric Mitterrand, as a "brave book, very brave, a kind of secular confession where each confession, as in Georges Perec's "Je me souviens…", starts with "Je regrette…".[20]

In 2017, neuropsychiatrist Louis Masquin, in the Catholic magazine La Croix, described the introduction of paedophilic literature on French television in Pivot's shows as the "reflection of the "paedophile adventure", "considered approximately normal".[21]

In 2019, Pivot wrote on Twitter that "cardinals, bishops and priests who rape children don't believe in heaven or hell", criticising the influence of the Vatican II reform. In September 2019, he declared on Twitter: "In my generation, boys looked for little Swedish girls who had the reputation of being more open than French girls. I imagine our surprise, our fear, if we had approached a Greta Thunberg". Julien Bayou, from the environmentalist party Europe Écologie – Les Verts, replied: "You're talking about a minor" and French feminist Caroline de Haas asked him to delete his post,[22] something he refused to do.[23] He was immediately defended by far-right essayist Éric Zemmour.[24] In December, Pivot apologised for allowing Gabriel Matzneff to describe his relationships with teenage girls and boys on his literary talk shows without challenging him.[25]

In July 2021, Pivot posted a tweet about actress Françoise Arnoul, who had just died, in which he remarked that "young people in the 1950s dreamed about her breasts. But the ones seen in The Wreck were not hers. She confessed it to me on a broadcast. Still a minor, she was not allowed to be filmed naked."[26]

References

edit- ^ Bernard Pivot président de l'Académie Goncourt: "Le destin ne se refuse pas" Archived 9 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, L'Express.

- ^ "A la tête de l'Académie". Académie Goncourt (in French). Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Nossiter, Adam (9 May 2024). "Bernard Pivot, Host of Influential French TV Show on Books, Dies at 89: For 15 years, French viewers watched Mr. Pivot on his weekly show, "Apostrophes," to decide what to read next". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Chronicle by Susan Heller Anderson Archived 27 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times.

- ^ French TV Show on Books Is Ending Archived 20 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times.

- ^ ARTS ABROAD; Adopting a Country, Then Crashing Its Best-Seller List Archived 27 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times.

- ^ Rosseau, Christine (6 May 2024). "Bernard Pivot, journaliste, créateur d'« Apostrophes », est mort". Le Monde (in French). Archived from the original on 6 May 2024. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ "Quiz : Quelle note auriez-vous obtenue à cette dictée de Bernard Pivot ?". Le Parisien. 7 May 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ Riding, Alan (10 September 2002). "Arts Abroad; Venturing Outside Actors Studio (to Paris)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ "James Lipton's Hero, French Cinephile Bernard Pivot, on How He Helped Shape 'Inside the Actors Studio'". The Hollywood Reporter. 4 March 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Bernard Pivot : Éléments de biographie". Académie Goncourt. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ Ouvrez les guillemets : émission du 26 novembre 1973, INA.

- ^ Édouard Brasey, L'effet Pivot, Éditions Ramsay, 1987, p.

- ^ L’Infini, Gallimard, n° 59, automne 1997, "La Question pédophile".

- ^ Est-ce que l'INA a fait disparaître les propos de Daniel Cohn-Bendit sur la sexualité des enfants ? Archived 4 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Libération.

- ^ "Gabriel Matzneff: the paedophile who hid in plain sight". The Spectator Australia. 20 February 2021. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Quand l'attrait de Gabriel Matzneff pour les jeunes enfants était dénoncé chez Pivot Archived 29 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Les Inrocks.

- ^ Michel Tournier sous la loupe de Bernard Pivot Archived 29 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Le Figaro.

- ^ Journal du dimanche Arrêté sur images[permanent dead link], Le JDD.

- ^ Frédéric Mitterrand : "Je regrette…", la chronique de Bernard Pivot Archived 29 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Le Journal du Dimanche.

- ^ Le lent changement de regard de la société sur la pédophilie Archived 29 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, La Croix.

- ^ Greta Thunberg's defiance upsets the patriarchy – and it's wonderful Archived 7 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian.

- ^ Bernard Pivot assume son tweet sexiste sur Greta Thunberg Archived 25 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Huffington Post.

- ^ Discours d'Eric Zemmour à la convention de la droite Archived 6 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Adoxa.

- ^ "French publishing boss claims she was groomed at age 14 by acclaimed author" Archived 8 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian.

- ^ "'Ses seins ont fait rêver' : l'Hommage de Bernard Pivot à l'actrice Françoise Arnoul crée le malaise". Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.