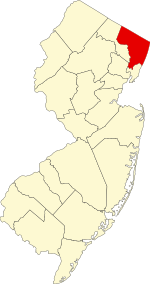

Bergen County is the most populous county in the U.S. state of New Jersey.[8] Located in the northeastern corner of New Jersey, Bergen County and its many inner suburbs constitute a highly developed part of the New York City metropolitan area, bordering the Hudson River; the George Washington Bridge, which crosses the Hudson, connects Bergen County with Manhattan. The county is part of the North Jersey region of the state.[9]

Bergen County | |

|---|---|

Atop the Hudson Palisades in Englewood Cliffs, overlooking the Hudson River, the George Washington Bridge, and the skyscrapers of Midtown Manhattan | |

Location within the U.S. state of New Jersey | |

New Jersey's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 40°58′N 74°04′W / 40.96°N 74.07°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1683 |

| Named for | Bergen, Norway or Bergen op Zoom, Netherlands[1] |

| Seat | Hackensack[2] |

| Largest municipality | Hackensack (population) Mahwah (area) |

| Government | |

| • County executive | James J. Tedesco III (D, term ends December 31, 2026) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 246.45 sq mi (638.3 km2) |

| • Land | 232.79 sq mi (602.9 km2) |

| • Water | 13.66 sq mi (35.4 km2) 5.5% |

| Population | |

| • Total | 955,732 |

| • Estimate | 957,736 |

| • Density | 3,900/sq mi (1,500/km2) |

| Demonym | Bergenite[7] |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional districts | 5th, 9th |

| Website | www |

| Range in altitude: Highest elevation: 1,152 ft (351 m) (Bald Mountain, in the Ramapo Mountains, in Mahwah). Lowest elevation: 0 ft (0 m) (sea level), at the Hudson River in Edgewater. | |

As of the 2020 United States census, the county's population was 955,732,[4][5] its highest decennial count ever and an increase of 50,616 (+5.6%) from the 905,116 recorded at the 2010 census,[10] which in turn reflected an increase of 20,998 (2.4%) from the 884,118 counted in the 2000 census.[11]

The county is divided into 70 municipalities, the most of any county in New Jersey, made up of 56 boroughs, nine townships, three cities, and two villages. Its most populous place, with 46,030 residents as of the 2020 census, is Hackensack,[5] which is also its county seat.[2] Mahwah covers the largest area of any municipality, at 26.19 square miles (67.8 km2).[11]

Bergen County is one of the largest commercial hubs in both New Jersey and the United States, generating over $6 billion in annual revenues from retailers in Paramus alone, despite blue laws keeping most stores in the county and especially Paramus itself (which has much stricter blue laws then the rest of the county) open only six days per week.[12] The county is one of the wealthiest counties in the United States, with a median household income of $109,497 (compared to $89,703 in New Jersey and $69,021 nationwide) and a per capita income of $55,710 (vs. $46,691 in the state and $37,638 in the U.S.) as of the 2017–2021 American Community Survey.[13] Bergen County has some of the highest home prices in New Jersey, with the median home price in 2022 exceeding $600,000.[14] The county's park system covers more than 9,000 acres (3,600 ha).[15]

Etymology

editThe origin of the name of Bergen County is a matter of debate. It is believed that the county is named after one of the earliest settlements, Bergen, in modern-day Hudson County, New Jersey. However, the origin of the township's name is debated. Several sources attribute the name to Bergen, Norway, while others attribute it to Bergen op Zoom in the Netherlands.[1] Some sources say that the name is derived from one of the earliest settlers of New Amsterdam (now New York City), Hans Hansen Bergen, a native of Norway, who arrived in New Netherland in 1633.[16][17]

History

editAt the time of first European contact, Bergen County was inhabited by Native American people, particularly the Lenape Nation, whose subgroups included the Tappan, Hackensack, and Rumachenanck (later called the Haverstraw), as named by the Dutch colonists.[18] Some of their descendants are included among the Ramapough Mountain Indians, recognized as a tribe by the state in 1980.[19] Their ancestors had moved into the mountains to escape encroachment by Dutch and English colonists. Their descendants reside mostly in the northwest of the county, in nearby Passaic County and in Rockland County, New York, tracing their Lenape ancestry to speakers of the Munsee language, one of three major dialects of their language.[20] Over the years, they absorbed other ethnicities by intermarriage.[21]

In the 17th century, the Dutch considered the area comprising today's Bergen and Hudson counties as part of New Netherland, their colonial province of the Dutch Republic. The Dutch claimed it after Henry Hudson (sailing for the Dutch East India Company) explored Newark Bay and anchored his ship at Weehawken Cove in 1609.[22] From an early date, the Dutch began to import African slaves to fill their labor needs. Bergen County eventually was the largest slaveholding county in the state, with nearly 20% of its population consisting of slaves in 1800.[23] The African slaves were used for labor at the ports to support shipping, as well as for domestic servants, trades, and farm labor.

Early settlement attempts by the Dutch colonists included Pavonia (1633), Vriessendael (1640), and Achter Col (1642), but the Native Americans repelled these settlements in Kieft's War (1643–1645) and the Peach War (1655).[24][25] European settlers returned to the western shores of the Hudson River in the 1660 formation of Bergen Township (now part of Jersey City, New Jersey), which would become one of the earliest permanent European settlements in present-day New Jersey.[26][27]

During the Second Anglo-Dutch War, on August 27, 1664, New Amsterdam's governor Peter Stuyvesant surrendered to the English Navy.[28] The English organized the Province of New Jersey in 1665, later splitting the territory into East Jersey and West Jersey in 1674. On November 30, 1675, the settlement Bergen and surrounding plantations and settlements were called Bergen County in an act passed by the province's General Assembly.[29] In 1683, Bergen (along with the three other original counties of East Jersey) was officially recognized as an independent county by the Provincial Assembly.[30][31]

Initially, Bergen County comprised only the land between the Hudson River and the Hackensack River, extending north to the border between East Jersey and New York.[32] In January 1709, the boundaries were extended to include all of the current territory of Hudson County (formed in 1840) and portions of the current territory of Passaic County (formed in 1837). The 1709 borders were described as follows:[32]

- "Beginning at Constable's Hook, so along the bay and Hudson's River to the partition point between New Jersey and the province of New York; along this line and the line between East and West Jersey† to the Pequaneck River; down the Pequaneck and Passaic Rivers to the sound; and so following the sound to Constable's Hook the place of beginning."

- † The line between East and West Jersey here referred to is not the line finally adopted and known as the Lawrence line, which was run by John Lawrence in September and October 1743. It was the compromise line agreed upon between Governors Daniel Coxe and Robert Barclay in 1682, which ran a little north of Morristown to the Passaic River; thence up the Pequaneck to forty-one degrees of north latitude; and thence by a straight line due east to the New York State line. This line being afterward objected to by the East Jersey proprietors, the latter procured the running of the Lawrence line.[32]

Bergen was the location of several battles and troop movements during the American Revolutionary War. Fort Lee's location on the bluffs of the New Jersey Palisades, opposite Fort Washington in Manhattan, made it a strategic position during the war. In November 1776, the Battle of Fort Lee took place as part of a British plan to capture George Washington and to resoundingly defeat the Continental Army, whose forces were divided and located in Fort Lee and Hackensack. After abandoning the defenses in Fort Lee and leaving behind considerable supplies, the Continental forces staged a hasty retreat through present-day Englewood, Teaneck, and Bergenfield, and across the Hackensack River at New Bridge Landing, one of the few sites where the river was crossed by a bridge. They destroyed the bridge to delay the British assault on Washington's headquarters in the village of Hackensack. The next day, George Washington retreated to Newark and left Hackensack via Polifly Road. British forces pursued, and Washington continued to retreat across New Jersey. The retreat allowed American forces to escape capture and regroup for subsequent successes against the British elsewhere in New Jersey later that winter.[33]

Soon after the Battle of Princeton in January 1777, British forces realized that they were not able to spread themselves thin across New Jersey. Local militia retook Hackensack and the rest of Bergen County. Bergen County saw skirmishes throughout the war as armies from both sides maneuvered across the countryside.

The Baylor Massacre took place in 1778 in River Vale, resulting in severe losses for the Continentals.[34]

In 1837, Passaic County was formed from parts of Bergen and Essex counties. In 1840, Hudson County was formed from Bergen. These two divisions took roughly 13,000 residents (nearly half of the previous population) from the county's rolls.[31][35]

In 1852, the Erie Railroad began operating major rail services from Jersey City on the Hudson River to points north and west via leased right-of-way in the county. This became known as the Erie Main Line, and is still in use for passenger service today.[36] The Erie later leased two other railroads built in the 1850s and 1860s, later known as the Pascack Valley Line and the Northern Branch, and in 1881 built a cutoff, now the Bergen County Line. There were two other rail lines in the county, ultimately known as the West Shore Railroad and the New York, Susquehanna, and Western.

In 1894, state law was changed to allow easy formation of municipalities with the borough form of government. This led to the "boroughitis" phenomenon, in which many new municipalities were created in a span of a few years.[37] There were 26 boroughs that were formed in the county in 1894 alone, with two more boroughs (and one new township) formed in 1895.[38] Ultimately 56 boroughs were incorporated in Bergen County, the highest number for any county in New Jersey.

On January 11, 1917, the Kingsland Explosion took place at a munitions factory in what is today Lyndhurst.[39] The explosion is believed to have been an act of sabotage by German agents, as the munitions in question were destined for Russia, part of the U.S.'s effort to supply allies before entrance into World War I.[40] After the U.S. entry into the war in April 1917, Camp Merritt was created in eastern Bergen County for troop staging. Beginning operations in August 1917, it housed 50,000 soldiers at a time, staging them for deployment to Europe via Hoboken. Camp Merritt was decommissioned in November 1919.[41]

The George Washington Bridge was completed in 1931, linking Fort Lee to Manhattan. This connection spurred rapid development in the post-World War II era, developing much of the county to suburban levels. Two lanes were added to the upper level in 1946 and a second deck of traffic on the bridge was completed in 1962, expanding its capacity to becoming the world's only 14-lane suspension bridge.[42] The bridge is the world's busiest motor vehicle bridge, carrying 104 million vehicles in 2019.[43]

In 1955, the United States Army established a Nike Missile station at Campgaw Mountain (in the west of the county) for the defense of the New York Metropolitan Area from strategic bombers. In 1959, the site was upgraded to house Nike-Hercules Missiles with increased range, speed, and payload characteristics. The missile site closed in June 1971.[44]

Geography

editBergen County is located at the northeastern corner of the state of New Jersey and is bordered by Rockland County, New York, to the north; by Manhattan and the Bronx in New York City, as well as by Westchester County, New York, across the Hudson River to the east; and within New Jersey, by Hudson County as well as a small border with Essex County to the south, and by Passaic County to the west.[45]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of the 2020 Census, the county had a total area of 246.45 square miles (638.3 km2), of which 232.79 square miles (602.9 km2) was land (94.5%) and 13.66 square miles (35.4 km2) was water (5.5%).[3]

Bergen County's highest elevation is Bald Mountain near the New York state line in Mahwah, at 1,164 feet (355 m) above sea level.[46][47] The county's lowest point is sea level, along the Hudson River, which in this region is a tidal estuary.

The sharp cliffs of the New Jersey Palisades lift much of the eastern boundary of the county up from the Hudson River. The relief becomes less pronounced across the middle section of the county, much of it being located in the Hackensack River valley or the Pascack Valley. In the northwestern portion of the county, Bergen County becomes hilly again and shares the Ramapo Mountains with Rockland County, New York.

The damming of the Hackensack River and a tributary, the Pascack Brook, produced three reservoirs in the county, Woodcliff Lake Reservoir (which impounds one billion gallons of water), Lake Tappan (3.5 billion gallons), and Oradell Reservoir, which allows United Water to provide drinking water to 750,000 residents of North Jersey, mostly in Bergen and Hudson counties.[48] The Hackensack River drains the eastern portion of the county through the New Jersey Meadowlands, a wetlands area in the southern portion of the county. The central portion is drained by the Saddle River and the western portion is drained by the Ramapo River. Both of these are tributaries of the Passaic River, which forms a section of the southwestern border of the county.

Climate

edit| Hackensack, New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Southeastern Bergen County lies at the edge of the humid subtropical climate zone (Cfa) according to the Köppen climate classification because its coldest month (January) averages above 26.6 °F / -3 °C.[50][51][52] In part due to Bergen's coastal location, its lower elevation, and the partial shielding of the county from colder air by the three ridges of the Watchung Mountains as well as by the higher Appalachians, the climate of Bergen County is milder than in New Jersey counties further inland such as Sussex County. Bergen County has a moderately sunny climate, averaging between 2,400 and 2,800 hours of sunshine annually.[53]

In recent years, average temperatures in the county seat of Hackensack have ranged from a low of 19 °F (−7 °C) in January to a high of 86 °F (30 °C) in July, although a record low of −15 °F (−26 °C) was recorded in February 1934 and a record high of 106 °F (41 °C) was recorded in July 1936. Average monthly precipitation ranged from 3.21 inches (82 mm) in February to 4.60 inches (117 mm) in July.[49]

Average monthly temperatures at the interchange of Route 17 and MacArthur Boulevard in Mahwah range from 28.5 °F in January to 73.8 °F in July. Using the 0 °C January isotherm, most of Bergen has a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa) except for higher areas in the Ramapo Mountains, which are Dfb, and along the Hudson River from Fort Lee downward, where Cfa exists.[54] Due to its location and elevation span, Bergen is the only county in New Jersey to have all three of the state's Köppen climate zones.[citation needed]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 12,601 | — | |

| 1800 | 15,156 | 20.3% | |

| 1810 | 16,603 | 9.5% | |

| 1820 | 18,178 | 9.5% | |

| 1830 | 22,412 | 23.3% | |

| 1840 | 13,223 | * | −41.0% |

| 1850 | 14,725 | 11.4% | |

| 1860 | 21,618 | 46.8% | |

| 1870 | 30,122 | 39.3% | |

| 1880 | 36,786 | 22.1% | |

| 1890 | 47,226 | 28.4% | |

| 1900 | 78,441 | 66.1% | |

| 1910 | 138,002 | 75.9% | |

| 1920 | 210,703 | 52.7% | |

| 1930 | 364,977 | 73.2% | |

| 1940 | 409,646 | 12.2% | |

| 1950 | 539,139 | 31.6% | |

| 1960 | 780,255 | 44.7% | |

| 1970 | 897,148 | 15.0% | |

| 1980 | 845,385 | −5.8% | |

| 1990 | 825,380 | −2.4% | |

| 2000 | 884,118 | 7.1% | |

| 2010 | 905,116 | 2.4% | |

| 2020 | 955,732 | 5.6% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 957,736 | [4][6] | 0.2% |

| Historical sources: 1790–1990[55] 1970–2010[11] 2020[4][5] * = Territorial change in previous decade | |||

2020 census

editAs of the 2020 United States census, the county had 955,732 people, 343,733 households, and 242,272 families. The population density was 3,900 inhabitants per square mile (1,505.8/km2). There were 367,383 housing units at an average density of 1,576 per square mile (608.5/km2). The county racial makeup was 56.90% White, 5.73% African American, 0.47% Native American, 16.59% Asian, and 10.17% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 21.41% of the population.[4]

There were 343,733 households, of which 29.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.1% were married couples living together, 24.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 13.9% had a male householder with no wife present and 29.5% were non-families. 14.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.18 and the average family size was 3.25.[4]

About 21.3% of the county's population was under age 18, 8.0% was from age 18 to 24, 36.7% was from age 25 to 44, and 17.0% was age 65 or older. The median age was 42.1 years. The gender makeup was 48.53% male and 51.14% female. For every 100 females, there were 94.3 males.[4]

The median household income was $108,827, and the median family income was $122,981. About 5.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.4% of those under age 18 and 7.7% of those age 65 or over.[4]

2010 census

editThe 2010 United States census counted 905,116 people, 335,730 households, and 238,704 families in the county. The population density was 3,884.5 per square mile (1,499.8/km2). There were 352,388 housing units at an average density of 1,512.3 per square mile (583.9/km2). The racial makeup was 71.89% (650,703) White, 5.80% (52,473) Black or African American, 0.23% (2,061) Native American, 14.51% (131,329) Asian, 0.03% (229) Pacific Islander, 5.04% (45,611) from other races, and 2.51% (22,710) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 16.05% (145,281) of the population.[10]

Of the 335,730 households, 32% had children under the age of 18; 56.1% were married couples living together; 10.9% had a female householder with no husband present and 28.9% were non-families. Of all households, 24.6% were made up of individuals and 10.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.66 and the average family size was 3.2.[10]

22.6% of the population was under the age of 18, 7.4% was from 18 to 24, 25.9% from 25 to 44, 29% from 45 to 64, and 15.1% was 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41.1 years. For every 100 females, the population had 92.9 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 89.8 males.[10]

Community diversity

editGiven its location as a suburban extension of Manhattan across the George Washington Bridge,[56] Bergen County has evolved a globally cosmopolitan ambience of its own, demonstrating a robust and growing demographic and cultural diversity with respect to metrics including nationality, religion, race, and domiciliary partnership. South Korea, Poland, and India are the three most common nations of birth for foreign-born Bergen County residents.[57]

Italian American

editItalian Americans have long had a significant presence in Bergen County; in fact, Italian is the most commonly identified first ancestry among Bergen residents (18.5%), with 168,974 Bergen residents were recorded as being of Italian heritage in the 2013 American Community Survey.[58]

To this day, many residents of the Meadowlands communities in the county's south are of Italian descent, most notably in South Hackensack (36.3%), Lyndhurst (33.8%), Carlstadt (31.2%), Wood-Ridge (30.9%) and Hasbrouck Heights (30.8%).[59] Saddle Brook (29.8%), Lodi (29.4%), Moonachie (28.5%), Garfield, Hackensack, and the southeastern Bergen towns were Italian American strongholds for decades, but their Italo-American demographics have diminished in recent years as more recent immigrants have taken their place.[60] At the same time, the Italian American population has grown in many of the communities in the northern half of the county, including Franklin Lakes,[61] Ramsey,[62] Montvale,[63] and Woodcliff Lake.[64]

Latin American

editThe diverse Hispanic and Latin American population in Bergen is growing in many areas of the county but is especially concentrated in a handful of municipalities, including Fairview (37.1%), Hackensack (25.9%), Ridgefield Park (22.2%), Englewood (21.8%), Bogota (21.3%), Garfield (20.1%), Cliffside Park (18.2%), Lodi (18.0%), and Bergenfield (17.0%).[65] Traditionally, many of the Latino residents were of Colombian and Cuban ancestry, although that has been changing in recent years. Englewood's Colombian community is the largest in Bergen County and among the top ten by percent of population in the United States (7.17%); Hackensack, Fairview, Bergenfield, Bogota, and Lodi also have notable populations.[66] The Cuban population is largest in Fairview, Ridgefield Park, Ridgefield, and Bogota, although the Cuban community is much bigger in Hudson County to the south.[67] Since 2000, an increasing number of immigrants from other countries (including Peru, Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, and Chile) as well as from the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico have entered the county. The diverse backgrounds of the local Latino community are best exemplified in Fairview, where 10% of the overall population hails from Central America, 7% from South America, and 9% from other Latin American countries, mainly those in the Caribbean. The borough of Fairview has the highest percentage of people of Salvadoran and Salvadoran American ancestry in the county, 12.4%.[68] The city of Hackensack has the highest percentage of people of Ecuadorian and Ecuadorian American ancestry in the county, 10.01%, with a total of approximately 4,500 living within city limits.[citation needed] Overall, Bergen County's Latino population has demonstrated a robust increase recently, growing from 145,281 as of the 2010 census count[10] to an estimated 165,442 as of 2013.[69]

Western European American

editIrish Americans and German Americans are the next largest individual ethnic groups in Bergen County, numbering 115,914 (12.7% of the county's total population) and 80,288 (8.8%) respectively in 2013.[58] As is the case with Italian Americans, these two groups developed sizable enclaves long ago and are now well established in all areas of the county. In 2023, Waldwick (30.43%), Ho-Ho-Kus (26.72%), and Hillsdale (24.94%) were reported as having the highest percentages of Irish American residents in the county.[70] The Council of Irish Associations of Greater Bergen County, based in Bergenfield, has hosted an annual Saint Patrick's Day parade in the county since 1982.[71]

Jewish American

editBergen County is home to the largest Jewish population in New Jersey.[72] Many municipalities in the county are home to a significant number of Jewish Americans, including Fair Lawn, Teaneck, Tenafly, Closter, Englewood, Englewood Cliffs, Fort Lee, Bergenfield, Woodcliff Lake, Paramus, and Franklin Lakes.[73] Teaneck, Fair Lawn, Englewood, and Bergenfield in particular have become havens for Bergen County's growing Orthodox Jewish communities, with a rising number of synagogues as well as supermarkets and restaurants offering kosher foods.[74] The largest Israeli American communities in Bergen County were in Fair Lawn (2.5%), Closter (1.4%), and Tenafly (1.3%) in 2000, representing three of the four largest in the state.[75] Altogether, 83,700 Bergen residents identified themselves as being of Jewish heritage in 2000, a number expected to show an increase per a 2014 survey of Jews in the county.[73][74] The Jewish Federation of Northern New Jersey is based in Paramus.[76]

Korean American

editSouth Koreans constituted the most prevalent foreign-born nationality in Bergen County, which was home to all of the nation's top ten municipalities by percentage of Korean population in 2010.[78]

The top ten municipalities in the United States as ranked by Korean American percentage of overall population in 2010 are illustrated in the following table. Palisades Park has Koreans that comprise the majority (53.7%) of the population in 2022:[79]

| Rank | Municipality | County | State | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Palisades Park[79] | Bergen County | New Jersey | 53.7% |

| 2 | Leonia | Bergen County | New Jersey | 26.5% |

| 3 | Ridgefield | Bergen County | New Jersey | 25.7% |

| 4 | Fort Lee | Bergen County | New Jersey | 23.5% |

| 5 | Closter | Bergen County | New Jersey | 21.2% |

| 6 | Englewood Cliffs | Bergen County | New Jersey | 20.3% |

| 7 | Norwood | Bergen County | New Jersey | 20.1% |

| 8 | Edgewater | Bergen County | New Jersey | 19.6% |

| 9 | Cresskill | Bergen County | New Jersey | 17.8% |

| 10 | Demarest | Bergen County | New Jersey | 17.3% |

One of the fastest-growing immigrant groups in Bergen County[80] is the Korean American community, which is concentrated along the Hudson River – especially in the area near the George Washington Bridge – and represented more than half of the state's entire Korean population as of 2000.[81] As of the 2022 American Community Survey, persons of Korean ancestry made up 6.5% of Bergen County's population,[82] the highest percentage for any county in the United States;[83] while the concentration of Koreans in Palisades Park, within Bergen County, is the highest density and percentage of any municipality in the United States,[84] at 53.7% of the borough's population.[79] Per the 2010 Census, Palisades Park was home to the highest total number (10,115)[85] of individuals of Korean ancestry among all municipalities in the state,[86] while neighboring Fort Lee had the second largest cluster (8,318),[87] and fourth highest proportion (23.5%, trailing Leonia (26.5%) and Ridgefield (25.7%)). All of the nation's top ten municipalities by percentage of Korean population in 2010 were located in Bergen County,[78] including Palisades Park, Leonia, Ridgefield, Fort Lee, Closter, Englewood Cliffs, Norwood, Edgewater, Cresskill, and Demarest, closely followed by Old Tappan. Virtually all of the municipalities with the highest Korean concentrations are located in the eastern third of the county, near the Hudson River, although Ridgewood has emerged as a Korean American nexus in western Bergen County,[88] and Paramus[89] and River Edge[90] in central Bergen County. Beginning in 2012, county election ballots were printed in the Korean language,[91] in addition to English and Spanish, given the U.S. Census Bureau's directive that Bergen County's Korean population had grown large enough to warrant language assistance during elections.[92] Between 2011 and 2017, the Korean population of Fair Lawn was estimated to have more than doubled.[93]

South Korean chaebols have established North American headquarters operations in Bergen County, including Samsung,[94] LG Corp,[95] and Hanjin Shipping.[96] In April 2018, the largest Korean-themed supermarket in Bergen County opened in Paramus.[97] In January 2019, Christopher Chung was sworn in as the first Korean-American mayor of Palisades Park.[98]

The political stature of Koreatown appears to be increasing significantly as well. Bergen County's growing Korean community[99][100][101][102] was cited by county executive Kathleen Donovan in the context of attorney Jae Y. Kim's appointment to Central Municipal Court judgeship in nearby Hackensack in January 2011.[101] Subsequently, in March 2012, leaders from Bergen County's Korean community announced they would form a grassroots political action committee to gain an organized voice in politics in the wake of the rejection of attorney Phillip Kwon to the New Jersey Supreme Court by a state legislative body,[102] and in July 2012, Kwon was appointed instead as deputy general counsel of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.[103] Jacqueline Choi was then sworn in as Bergen County's first female Korean American assistant prosecutor in September 2012.[104] According to The Record, the U.S. Census Bureau has determined that the county's Korean American population has grown enough to warrant language assistance during elections,[105] and Bergen County's Koreans have earned significant political respect.[106][107][108] As of May 2014, Korean Americans had garnered at least four borough council seats in Bergen County.[109] In November 2016, Ellen Park was elected to the borough council in nearby Englewood Cliffs,[110] while namesake Daniel Park was elected to the borough council in nearby Tenafly in November 2013.[111]

Polish American

editPolish Americans are well represented in western Bergen County and are growing as a community, with 59,294 (6.5%) of residents of Polish descent residing in the county as of the 2013 American Community Survey.[58] The community's cultural and commercial heart has long been centered in Wallington, where 45.5% of the population is of Polish descent; this is the largest concentration among New Jersey municipalities and the seventh-highest in the United States.[112] The adjacent city of Garfield has also become a magnet for Polish immigrants, with 22.9% of the population identifying themselves as being of Polish ancestry, the third highest concentration in the state.[112]

African American

editThe county's African American community is almost entirely concentrated in three municipalities: Englewood (10,215 residents, accounting for 38.98% of the city's total population), Teaneck (11,298; 28.78%), and Hackensack (10,518; 24.65%). Collectively, these three areas account for nearly 70% of the county's total African American population of 46,568, and in fact, blacks have had a presence in these towns since the earliest days of the county. In sharp contrast, African Americans comprise less than 2% of the total in most of Bergen's other municipalities.[113] In Englewood, the African American population is concentrated in the Third and Fourth wards of the western half of the city, while the northeastern section of Teaneck has been an African American enclave for several decades.[114] In 2014, Teaneck selected its first female African-American mayor.[115] Hackensack's long-established African American community is primarily located in the central part of the city, especially in the area near Central Avenue and First Street.[116] Bergen County's black population has declined from 52,473 counted in the 2010 Census[10] to an estimated 50,478 in 2012.[69] Other county municipalities with a sizeable minority of African Americans include Bergenfield (7.7%), Bogota (9.4%), Garfield (6.5%), Lodi (7.5%) and Ridgefield Park (6.4%).[117]

Indian American

editIndian Americans represent a rapidly growing demographic in Bergen County, enumerating over 40,000 individuals in 2013,[69] a significant increase from the 24,973 counted in the 2010 Census,[10] and represent the second largest Asian ethnic group in Bergen County, after Korean Americans. The biggest clusters of Indian Americans are located in Hackensack,[118] Ridgewood,[119] Fair Lawn,[120] Paramus,[121] Teaneck,[122] Mahwah,[123] Bergenfield,[124] Lodi,[125] and Elmwood Park.[126] Within the county's Indian population is America's largest Malayali community,[127] and Kerala-based Kitex Garments, India's largest children's clothing manufacturer, opened its first U.S. office in Montvale in October 2015.[128] Glen Rock resident Gurbir Grewal, a member of Bergen County's growing Indian American Sikh community, was sworn into the position of county prosecutor in 2016,[129] and an architecturally notable Sikh gurudwara resides in Glen Rock,[130] while a similarly prominent Hindu mandir has been built in Mahwah.[131] The public library in Fair Lawn began a highly attended Hindi language (हिन्दी) storytelling program in October 2013.[132] The affluent municipalities of northern Bergen County are witnessing significant growth in their Indian American communities, including Glen Rock, into which up to 90% of this constituency was estimated by one member in 2014 to have moved within the preceding two-year period alone.[133] In February 2015, the board of education of the Glen Rock Public Schools voted to designate the Hindu holy day Diwali as an annual school holiday, making it the first district in the county to close for the holiday,[134] while thousands celebrated the first county-wide celebration of Diwali under a unified sponsorship banner in 2016.[135] An annual "Holi in the Village" festival of colors has been launched in Ridgewood.[136]

Russian (and other former Soviet) American

editFair Lawn, Tenafly, Alpine, and Fort Lee are hubs for Russian Americans, including a growing community of Russian Jews.[137] Garfield is home to an architecturally prominent Russian Orthodox church.[138] Likewise, Ukrainian Americans, Georgian Americans, and Uzbek Americans have more recently followed the path of their Russian American predecessors to Bergen County, particularly to Fair Lawn. The size of Fair Lawn's Russian American presence has prompted an April Fool's satire titled, "Putin Moves Against Fair Lawn".[139] The Armenian American population in Bergen is dispersed throughout the county, but its most significant concentration is in the southeastern towns near the George Washington Bridge. The victims of the Armenian genocide are recognized annually at the Bergen County Courthouse in Hackensack.[140]

Filipino American

editBergenfield, along with Paramus, Hackensack,[141] New Milford, Dumont,[142] Fair Lawn, and Teaneck,[122] have become growing hubs for Filipino Americans. Taken as a whole, these municipalities are home to a significant proportion of Bergen County's Philippine population.[124][143][144][145] A census-estimated 20,859 Filipino Americans resided in Bergen County as of 2013,[69] embodying an increase from the 19,155 counted in 2010.[146] Between 2000 and 2010, the Filipino-American population of Bergenfield grew from 11.7%, or 3,081 residents, to 17.1%, or 4,569,[147] and increasing further to 5,062 (18.4%) by 2016.[148] Bergenfield is informally known as the Little Manila of Bergen County, with a significant concentration of Filipino residents and businesses.[149][150] In the late 1990s, Bergenfield became the first municipality on the East Coast of the United States to elect a Filipino mayor, Robert C. Rivas.[citation needed] The annual Filipino American Festival is held in Bergenfield.[151] The Philippine-American Community of Bergen County (PACBC) organization is based in Paramus,[152] while other Filipino organizations are based in Fair Lawn[142][153][154] and Bergenfield.[155] Bergen County's culturally active Filipino community repatriated significant financial assistance to victims of Typhoon Haiyan, which ravaged the Philippines in November 2013.[142] Between 2011 and 2017, Fair Lawn's Filipino population was estimated to have more than doubled.[156] In 2021, the multinational conglomerate Jollibee restaurant chain based in Metro Manila, planned to open its first Bergen County location in East Rutherford.[157]

Chinese American

editThe Chinese American population is also spread out, with sizable populations in Fort Lee, Paramus, Ridgewood, River Edge, and Englewood Cliffs.[158] Fort Lee and Paramus have the highest total number of Chinese among Bergen municipalities, while Englewood Cliffs has the highest percentage (8.42%). Several school districts throughout the county have added Mandarin to their curricula.

Japanese American

editThe Japanese community, which includes a significant number of Japanese nationals, has long had a presence in Fort Lee, with over a quarter of the county's total Japanese population living in that borough alone. Adjacent Edgewater has also developed an active Japanese American community, particularly after the construction of the largest Japanese-oriented commercial center on the U.S. East Coast in this borough. As of March 2011, about 2,500 Japanese Americans lived in Fort Lee and Edgewater combined; this is the largest concentration of Japanese Americans in New Jersey.[159] The remainder of Bergen County's Japanese residents are concentrated in northern communities, including Ridgewood. The Japanese-American Society of New Jersey is based in Fort Lee.[160]

Balkan American

editGreek Americans have had a fairly sizable presence in Bergen for several decades, and according to 2000 census data, the Greek community numbered 13,247 county-wide.[161] Greek restaurants are abundant in Bergen County.[162] The largest concentrations of Greeks by percentage in the county are in Englewood Cliffs (7.2%), Alpine (5.2%), Fort Lee (3.7%), and Palisades Park (3.5%).[163] Macedonian Americans and Albanian Americans have arrived relatively recently in New Jersey[164][165][166][167] but have quickly established Bergen County enclaves, roughly in tandem, in Garfield, Elmwood Park, and Fair Lawn.

Iranian American

editA relatively recent community of Iranian Americans has emerged in Bergen County,[168][169] including those in professional occupations scattered throughout the county.

Same-sex couples

editSame-sex couples headed one in 160 households in 2010,[170] prior to the commencement of same-sex marriages in New Jersey on October 21, 2013.[171] On June 28, 2016, Bergen County officials for the first time raised the rainbow-colored gay pride flag at the county administration building in Hackensack to commemorate the gay rights movement.[172]

Muslims

editBergen County also has a moderate-sized Muslim population, which numbered 6,473 as of the 2000 census.[73] Teaneck and Hackensack have emerged as the two most significant Muslim enclaves in the county, with the American Muslim Union's 18th annual brunch gathering held in Teaneck in 2016.[173][174] Bergen's Muslim population primarily consists of Arab Americans, South Asian Americans, African Americans, and more recently, Macedonian Americans and Albanian Americans, although many members of these groups practice other religions.[175] While Arab Americans have not established a significant presence in any particular municipality, in total there are 11,755 county residents who indicated Arab ancestry in the 2000 census.[176] The overwhelming majority of Bergen's Arab American population (64.3%) is constituted by persons of Lebanese (2,576),[177] Syrian (2,568),[178] and Egyptian (2,417)[179] descent. The county's diners provide late-night and pre-dawn dining options during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan.[180]

Transportation

editAs of May 2010[update], the county had a total of 2,988.59 miles (4,809.67 km) of roadways, of which 2,402.78 miles (3,866.90 km) are maintained by the municipality, 438.97 miles (706.45 km) by Bergen County, 106.69 miles (171.70 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation, 11.03 miles (17.75 km) by the Palisades Interstate Parkway Commission, 27.94 miles (44.97 km) by the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and 1.18 miles (1.90 km) by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.[182][183][184]

Bergen County has a highly developed road network, including the northern termini of the New Jersey Turnpike (a portion of Interstate 95) and the Garden State Parkway, the eastern terminus of Interstate 80, and a portion of Interstate 287.

Other roadways that serve Bergen County include:[185]

- U.S. highways

- State highways

- Other highways

Bridges and Tunnels

The George Washington Bridge, connecting Fort Lee in Bergen County across the Hudson River to the Upper Manhattan section of New York City, is the world's busiest motor vehicle bridge.[186][187] Access to New York City is alternatively available for motorists through the Lincoln Tunnel and Holland Tunnel in Hudson County. Access across the Hudson River to Westchester County in New York is available using the Tappan Zee Bridge in neighboring Rockland County, New York.

As of May 2010[update], the county had a total of 2,988.59 miles (4,809.67 km) of roadways, of which 2,402.78 miles (3,866.90 km) are maintained by the municipality, 438.97 miles (706.45 km) by Bergen County, 106.69 miles (171.70 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation, 11.03 miles (17.75 km) by the Palisades Interstate Parkway Commission, 27.94 miles (44.97 km) by the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and 1.18 miles (1.90 km) by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.[182][183][184]

Public Transportation

Train service is available on three lines from NJ Transit: the Bergen County Line, the Main Line, and the Pascack Valley Line.[189][190] They run north–south to Hoboken Terminal with connections to the PATH train. NJ Transit also offers connecting service to New York Penn Station and Newark Penn Station at Secaucus Junction. Connections are also available at Hoboken Terminal to the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail and New York Waterways ferry service to the World Financial Center and other destinations. Despite the name, the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail does not yet run into Bergen County, although a northward extension from Hudson County to Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, known as the Northern Branch Corridor Project, has been advanced to the draft environmental impact statement stage by NJ Transit.[191] The proposed Passaic-Bergen Rail Line, with two station stops in Hackensack, has not advanced since its 2008 announcement. The Access to the Region's Core rail tunnel project would have allowed many Bergen County railway commuters a one-seat ride into Manhattan but was canceled in October 2010.[192][193]

Local and express bus service is available from NJ Transit and private companies such as Academy Bus Lines, and Coach USA, offering transport within Bergen County, elsewhere in New Jersey, and to the Port Authority Bus Terminal and George Washington Bridge Bus Station in New York City. In studies conducted to determine the best possible routes for the Bergen BRT (bus rapid transit) system, it has been determined the many malls and other "activity generators" in the vicinity of the intersection of routes 4 and 17 would constitute the core of any system.[194][195][196][197] While no funding has for construction of the project has been identified, a study begun in 2012 will define the optimal routes.[198][199][200]

Airports

There is one airport in the county, Teterboro Airport in Teterboro, which is operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.[201] The three busiest commercial airports in the New York City metropolitan area, namely JFK International Airport, Newark Liberty International Airport, and LaGuardia Airport, are all located within 25 miles of Bergen County.

For the main surface-street routes through the county, see List of county routes in Bergen County, New Jersey.

Education

editTertiary education

editBergen County is home to several colleges and universities:

- Bergen Community College – Paramus, with other centers in Hackensack and Lyndhurst[202]

- Eastwick College – Ramsey and Hackensack[203]

- Fairleigh Dickinson University – Teaneck and Hackensack[204]

- Felician University – Lodi and Rutherford[205]

- Ramapo College – Mahwah[206]

Saint Peter's University formerly operated a campus in Englewood Cliffs. This campus, on the site of the former Englewood Cliffs College, was active from 1975 until its official closure in August 2018.[207] Berkeley College formerly operated a campus in Paramus but announced the closure of this campus in spring 2022, thereafter consolidating it with the college's campus in Woodland Park (in Passaic County).[citation needed]

School districts

editThe county has the following school districts:[208][209][210]

- K-12

- Bergenfield Public School District

- Bogota Public Schools

- Cliffside Park School District

- Cresskill Public Schools

- Dumont Public Schools

- Edgewater Public Schools

- Elmwood Park Public Schools

- Emerson School District

- Englewood Public School District

- Fair Lawn Public Schools

- Fort Lee School District

- Garfield Public Schools

- Glen Rock Public Schools

- Hackensack Public Schools

- Hasbrouck Heights School District

- Leonia Public Schools

- Lodi Public Schools

- Lyndhurst School District

- Mahwah Township Public Schools

- Midland Park School District

- New Milford School District

- North Arlington School District

- Palisades Park Public School District

- Paramus Public Schools

- Park Ridge Public Schools

- Ramsey Public School District

- Ridgefield Park Public Schools

- Ridgefield School District

- Ridgewood Public Schools

- Rutherford School District

- Saddle Brook Public Schools

- Teaneck Public Schools

- Tenafly Public Schools

- Waldwick Public School District

- Wallington Public Schools

- Westwood Regional School District – Regional

- Wood-Ridge School District

- Secondary (9-12, except as noted)

- Bergen County Technical Schools

- Carlstadt-East Rutherford Regional School District

- Northern Highlands Regional High School

- Northern Valley Regional High School District

- Pascack Valley Regional High School District

- Ramapo Indian Hills Regional High School District

- River Dell Regional School District – (7–12)

- Elementary (K-8, except as noted)

- Allendale School District

- Alpine Public School District

- Carlstadt Public Schools

- Closter Public Schools

- Demarest Public Schools

- East Rutherford School District

- Englewood Cliffs Public Schools

- Fairview Public Schools

- Franklin Lakes Public Schools

- Harrington Park School District

- Haworth Public Schools

- Hillsdale Public Schools

- Ho-Ho-Kus School District

- Little Ferry Public Schools

- Maywood Public Schools

- Montvale Public Schools

- Moonachie School District

- Northvale Public Schools

- Norwood Public School District

- Oakland Public Schools

- Old Tappan Public Schools

- Oradell Public School District (K–6)

- River Edge Elementary School District (K–6)

- River Vale Public Schools

- Rochelle Park School District

- Saddle River School District (K–5)

- South Hackensack School District

- Upper Saddle River School District

- Woodcliff Lake Public Schools

- Wyckoff School District

The Rockleigh Borough School District is a non-operating school district.[208] Teterboro Borough School District was a non-operating school district; it is now in the Hasbrouck Heights district.[210][211]

County-wide school districts include Bergen County Technical Schools and Bergen County Special Services School District. South Bergen Jointure Commission also has special education services for the south of the county.

Bergen has some 45 public high schools and at least 23 private high schools. Three of the top ten municipal high schools out of 339 schools in New Jersey were located in Bergen County, according to a 2014 ranking by New Jersey Monthly magazine, including Northern Highlands Regional High School in Allendale (#3), Pascack Hills High School in Montvale (#7), and Glen Rock High School in Glen Rock (#8).[212] The magazine's list did not include the Bergen County Academies, which as the county's public magnet high school in Hackensack has continued to be recognized by various rankings as one of the best high schools in the United States.[213] In 2014, BCA had an average HSPA score of 294 out of 300 and an average SAT score of 2103 out of 2400.[214]

There is a school for Japanese citizen students, the New Jersey Japanese School, in Oakland, in the northwestern portion of Bergen County. In 1987, there were five juku (Japanese-style cram schools) in the county, with two of them in Fort Lee.[215]

Arts and culture

editThe Bergen Performing Arts Center (PAC) is based in Englewood, while numerous museums are located throughout the county. In September 2014, the Englewood-based Northern New Jersey Community Foundation announced an initiative known as ArtsBergen, a centralizing body with the goal of connecting artists and arts organizations with one another in Bergen County.[216]

Educational and cultural

edit- New Jersey Naval Museum, Hackensack. At the museum, the USS Ling is moored in the Hackensack River and is available for tours as a museum ship.[219]

- Aviation Hall of Fame and Museum of New Jersey, located at Teterboro Airport in Teterboro.[220]

- Bergen Museum of Art & Science, Hackensack.[221]

- Buehler Challenger & Science Center, Paramus – located on the campus of Bergen Community College.[222]

- Meadowlands Environment Center, Lyndhurst.[223]

- Tenafly Nature Center, Tenafly[224]

- Puffin Foundation, Teaneck[225]

- Maywood Station Museum, Maywood[226]

- Bergen Performing Arts Center, Englewood[227]

Commercial and entertainment

edit- MetLife Stadium, which replaced Giants Stadium, in East Rutherford, is the home of the New York Giants and the New York Jets of the National Football League. At a construction cost of approximately $1.6 billion,[218] it was the most expensive stadium ever built until being passed by SoFi Stadium in 2020.[217][228]

- Meadowlands Arena, East Rutherford (formerly known as the Izod Center, the Continental Airlines Arena and the Brendan Byrne Arena). Opened in 1981, it was formerly home to the New Jersey Devils of the National Hockey League, the New Jersey Nets of the National Basketball Association, and the Seton Hall University Pirates men's basketball team. The arena closed on April 3, 2015.[229]

- Meadowlands Racetrack, East Rutherford

- Garden State Plaza, Paramus, is one of the largest and highest revenue-producing shopping malls in the United States.

- The Shops at Riverside, shopping mall, Hackensack (formerly known as Riverside Square Mall)

- Paramus Park, shopping mall, Paramus

- The Outlets at Bergen Town Center, shopping mall, Paramus (formerly known as the Bergen Mall)

- Fashion Center, shopping mall, Paramus

- H Mart, Asian shopping plaza and supermarket, Ridgefield

- Mitsuwa Marketplace, Japanese shopping plaza and supermarket, Edgewater

- American Dream Meadowlands, retail and entertainment complex that opened on October 25, 2019.[230]

Government

editCounty government

editBergen has had a county executive form of government since voters chose the first executive in 1986,[231] joining Atlantic, Essex, Hudson and Mercer counties as one of the 5 of 21 New Jersey counties with an elected executive.[232] The executive oversees the county's business, while the seven-member Bergen County Board of Commissioners has a legislative and oversight role. The Commissioners are elected at-large to three-year terms in office on a staggered basis, with either two or three seats coming up for election each November in a three-year cycle. All members of the governing body are elected at-large on a partisan basis as part of the November general elections.[233][234] In 2018, Commissioners were paid $28,312 and the Commissioner chairman was paid an annual salary of $29,312.[235] Day-to-day oversight of the operation of the county and its departments is delegated to the County Administrator, Thomas J. Duch.[236] Duch took the position in June 2021, succeeding Julien X. Neals who was appointed as a federal judge.[237] As of 2024[update], the Bergen County Executive is James J. Tedesco III (D, Paramus), whose four-year term of office ends December 31, 2026.[238] Bergen County's Commissioners are (with terms for Chair and Vice Chair ending every December 31):[239][240][233][241][242][243][244]

| Commissioner | Party, Residence, Term |

|---|---|

| Chair Germaine M. Ortiz | D, Emerson, 2025[245] |

| Vice Chair Mary J. Amoroso | D, Mahwah, 2025[246] |

| Rafael Marte | D, Bergenfield, 2026 |

| Thomas J. Sullivan Jr. | D, Montvale, 2025[247] |

| Steven A. Tanelli | D, North Arlington, 2024[248] |

| Joan Voss | D, Fort Lee, 2026[249] |

| Tracy Silna Zur | D, Franklin Lakes, 2024[250] |

Pursuant to Article VII Section II of the New Jersey State Constitution, each county in New Jersey is required to have three elected administrative officials known as "constitutional officers." These officers are the County Clerk and County Surrogate (both elected for five-year terms of office) and the County Sheriff (elected for a three-year term).[251] Bergen County's constitutional officials are:[233][252]

| Title | Representative |

|---|---|

| County Clerk | John S. Hogan (D, Northvale, 2026),[253][254] |

| Sheriff | Anthony Cureton (D, Englewood, 2024)[255][256] |

| Surrogate | Michael R. Dressler (D, Cresskill, 2026).[257][258][233][259] |

The Bergen County Prosecutor is Mark Musella.[260] Musella succeeded acting prosecutor Dennis Calo, who was sworn into office in January 2018 after Gurbir Grewal of Glen Rock left office to become New Jersey Attorney General.[261] Bergen County constitutes Vicinage 2 of the New Jersey Superior Court, which is seated at the Bergen County Justice Center in Hackensack; the Assignment Judge for Vicinage 2 is Bonnie J. Mizdol.[262]

In March 2023, Rafael Marte was selected to fill the seat expiring in December 2023 that had been held by Ramon Hache until he resigned from office earlier that month.[263]

In 2014, Freeholder James Tedesco challenged incumbent Kathleen Donovan on a platform that highlighted his own plan to merge the Bergen County Police Department with the sheriff's office, as well as Donovan's connections to recent scandals in the New Jersey state government, including the nationally reported "Bridgegate" scandal and alleged campaign finance abuse among her staff.[264] Election results showed Tedesco with 54.2% of the vote (107,958), ahead of Donovan with 45.8% (91,299),[265] in a race in which Tedesco's campaign spending nearly $1 million, outspending Donovan by a 2–1 margin; that sweep mirrored that by neighboring Passaic County Democrats, who also defeated the three Republicans elected there in 2010, in the election in 2013, although voters in Passaic County would elect their first Republican candidate since 2013 to the then-renamed Board of County Commissioners in 2021. No Republican has won county-wide office in Bergen County since 2013.[266]

In November 2010, Republican County Clerk Kathleen Donovan won the race for County Executive, defeating Dennis McNerney in his bid for a third term. Three incumbent Freeholders, Chairman James Carroll, Freeholder Elizabeth Calabrese, and Freeholder John Hogan were all defeated by Republican challengers Franklin Lakes Mayor Maura DeNicola, former River Edge Councilman John Felice, and Cliffside Park resident John Mitchell. Incumbent Bergen County Sheriff Leo McGuire also failed in his bid for a third term as Emerson Police Chief Mike Saudino defeated him. As a result of the 2010 elections, Republicans controlled Bergen County government for the first time in nearly a decade, with County Executive Kathleen Donovan and a 5–2 majority on the Board of Chosen Freeholders.[267] Saudino would later face backlash over his remarks disparaging Black Americans and Sikhs—including remarks about Gurbir Grewal, who was the Bergen County prosecutor at the time—and resigned his position in 2018.[268]

Law enforcement

editNegotiations to merge the Bergen County Police Department with the Sheriff's Office began in 2015, and were finally completed in 2021. The county Police Department was created in 1917.[269][270]

The Bergen County court system consists of a number of municipal courts handling traffic court and other minor matters, plus the Bergen County Superior Court which handles more serious offenses. Law enforcement at the county level includes the Bergen County Sheriff's Office and the Bergen County Prosecutor's Office. Bergen County's first female police chief took office in September 2015, as police chief of Bergenfield.[271] In August 2015, a branding campaign was launched to highlight county government services, with its centerpiece being the official seal of Bergen County, depicting a Dutch settler shaking hands with a Native American. The county's contemporaneous executive James Tedesco made an approximately $5,000 private donation to initiate the effort in the form of a nine-foot rendering of this seal woven into the carpet of the county executive's office.[272]

Highlands protection

editIn 2004, the New Jersey Legislature passed the Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act, which regulates the New Jersey Highlands region. A portion of the northwestern area of the county, comprising the municipalities of Oakland and Mahwah, was included in the highlands preservation area and is subject to the rules of the act and the Highlands Water Protection and Planning Council, a division of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.[273] Some of the territory in the protected region is classified as being in the highlands preservation area, and thus subject to additional rules.[274]

Federal representatives

editThe county is part of two Congressional Districts: the 5th District covering the northern portion of the county and the 9th most of the south.[275] For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 5th congressional district is represented by Josh Gottheimer (D, Wyckoff).[276][277] For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 9th congressional district was represented by Bill Pascrell (D, Paterson) until his death in August 2024.[278][279]

State representatives

editThe 70 municipalities of Bergen County are represented by six separate state legislative districts.[280][281]

Politics

editThe county is characterized by a divide between mostly Republican communities in the north and northwest of the county, and mostly Democratic communities in its center and southeast. That dichotomy largely remained in place for quite a while, until 2020. Mirroring the national "suburban revolt" against President Donald Trump, Democratic candidate Joe Biden made significant gains in the northern portion of the county, winning in many affluent and typically Republican voting communities, such as River Vale, Ho-Ho-Kus, Ramsey, Allendale, Hillsdale, and Montvale, winning in Upper Saddle River by a mere 2 vote margin. He also won somewhat less affluent suburban towns such as Mahwah, Waldwick, and Midland Park, along with surpassing the margins of victory obtained by Hillary Clinton in municipalities like Fair Lawn, Glen Rock, Ridgewood, and wealthier southern Bergen towns like Rutherford (although the results in most of the rest of southern Bergen largely stayed the same compared to 2016 - either Biden or Trump barely won the more blue-collar towns of Carlstadt (Trump, by 57 votes)/East Rutherford (Biden, 485)/Lyndhurst (Trump, 68)/Moonachie (Biden, 48)/North Arlington (Trump, just 5)/South Hackensack (Biden, 88), while Trump's margins of defeat shrank in Garfield/Lodi, and his margin of victory grew in Wallington, all compared to 2016).[283][284][285][286] As of October 1, 2021, there were a total of 688,213 registered voters in Bergen County, of whom 265,251 (38.5%) were registered as Democrats, 150,812 (21.9%) were registered as Republicans, and 265,186 (38.5%) were registered as unaffiliated. There were 6,965 voters (1.0%) registered to other parties.[287] Among the county's 2010 Census population, 61.4% were registered to vote, including 77.4% of those ages 18 and over.[288][289]

In the 2020 presidential election, Joe Biden won the county by the largest margin for a Democrat since 1964, and marked the first time the county voted to the left of the state since 1904. In the 2016 presidential election, Democrat Hillary Clinton received 231,211 votes here (54.8%), ahead of Republican Donald Trump with 175,529 votes (41.6%) and other candidates with 19,827 votes (4.6%), among the 426,567 ballots cast by the county's 588,362 registered voters, for a turnout of 73%.[290] In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 212,754 votes here (54.8%), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 169,070 votes (43.5%) and other candidates with 3,583 votes (0.9%), among the 388,425 ballots cast by the county's 551,745 registered voters, for a turnout of 70.4%).[291][292] In the 2008 presidential election, Barack Obama received 225,367 votes here (53.9%), ahead of Republican John McCain with 186,118 votes (44.5%) and other candidates with 3,248 votes (0.8%), among the 418,459 ballots cast by the county's 544,730 registered voters, for a turnout of 76.8%.[293]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2024 | 210,870 | 47.51% | 224,863 | 50.66% | 8,111 | 1.83% |

| 2020 | 204,417 | 41.06% | 285,967 | 57.44% | 7,454 | 1.50% |

| 2016 | 175,529 | 41.57% | 231,211 | 54.76% | 15,473 | 3.66% |

| 2012 | 169,070 | 43.80% | 212,754 | 55.12% | 4,166 | 1.08% |

| 2008 | 186,118 | 44.75% | 225,367 | 54.19% | 4,424 | 1.06% |

| 2004 | 189,833 | 47.43% | 207,666 | 51.88% | 2,745 | 0.69% |

| 2000 | 152,731 | 41.65% | 202,682 | 55.27% | 11,308 | 3.08% |

| 1996 | 141,164 | 38.90% | 191,085 | 52.66% | 30,638 | 8.44% |

| 1992 | 178,223 | 44.21% | 171,104 | 42.44% | 53,810 | 13.35% |

| 1988 | 226,885 | 58.19% | 160,655 | 41.20% | 2,393 | 0.61% |

| 1984 | 268,507 | 63.22% | 155,039 | 36.50% | 1,172 | 0.28% |

| 1980 | 232,043 | 55.89% | 139,474 | 33.60% | 43,640 | 10.51% |

| 1976 | 237,331 | 55.86% | 180,738 | 42.54% | 6,784 | 1.60% |

| 1972 | 285,458 | 65.34% | 147,155 | 33.68% | 4,281 | 0.98% |

| 1968 | 224,911 | 54.45% | 162,182 | 39.27% | 25,944 | 6.28% |

| 1964 | 157,899 | 40.13% | 234,849 | 59.69% | 717 | 0.18% |

| 1960 | 224,969 | 58.92% | 156,165 | 40.90% | 674 | 0.18% |

| 1956 | 254,334 | 75.22% | 82,169 | 24.30% | 1,610 | 0.48% |

| 1952 | 212,842 | 69.22% | 93,373 | 30.37% | 1,287 | 0.42% |

| 1948 | 142,657 | 65.70% | 69,132 | 31.84% | 5,342 | 2.46% |

| 1944 | 142,836 | 65.00% | 76,350 | 34.74% | 566 | 0.26% |

| 1940 | 131,588 | 63.01% | 76,541 | 36.65% | 694 | 0.33% |

| 1936 | 89,628 | 49.28% | 91,107 | 50.09% | 1,143 | 0.63% |

| 1932 | 86,885 | 52.42% | 73,921 | 44.60% | 4,937 | 2.98% |

| 1928 | 89,105 | 63.62% | 50,373 | 35.96% | 589 | 0.42% |

| 1924 | 60,803 | 69.41% | 16,844 | 19.23% | 9,951 | 11.36% |

| 1920 | 47,512 | 76.26% | 12,396 | 19.90% | 2,397 | 3.85% |

| 1916 | 18,494 | 60.05% | 11,530 | 37.44% | 773 | 2.51% |

| 1912 | 5,087 | 20.46% | 9,978 | 40.12% | 9,803 | 39.42% |

| 1908 | 14,043 | 61.51% | 7,629 | 33.42% | 1,158 | 5.07% |

| 1904 | 9,957 | 54.65% | 7,301 | 40.08% | 960 | 5.27% |

| 1900 | 9,086 | 56.91% | 6,458 | 40.45% | 422 | 2.64% |

| 1896 | 8,545 | 62.07% | 4,531 | 32.91% | 690 | 5.01% |

In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 127,386 ballots cast (48.0%) in the county, ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 121,446 votes (45.8%), Independent Chris Daggett with 12,452 votes (4.7%), and other candidates with 1,262 votes (0.5%), among the 265,223 ballots cast by the county's 530,460 registered voters, yielding a 50.0% turnout.[295] In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 136,178 ballots cast (60.2%), ahead of Democrat Barbara Buono with 87,376 votes (38.7%) and other candidates with 2,515 votes (1.1%), among the 226,069 ballots cast for governor by the county's 527,491 registered voters, yielding a 42.9% turnout. This is the only time Bergen County voted for a Republican in a gubernatorial election in the 21st century.[296] In the 2017 gubernatorial election, Democrat Phil Murphy received 56.7% of the vote (129,265 votes) to Republican Kim Guadagno's 41.6% (94,904 votes); the county's third-largest pro-Democratic margin ever, behind both 1989 (Jim Florio's first run; 165,104 - 59.2%), and 1973 (Brendan Byrne's first run; 196,661 - 64%).[297] In the 2021 gubernatorial election, Democratic Governor Phil Murphy received 52.5% of the vote (145,150 votes) to Republican Jack Ciattarelli's 46.9% (129,644 votes).

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 47.1% 126,272 | 52.3% 140,220 |

| 2017 | 41.6% 94,904 | 56.7% 129,265 |

| 2013 | 60.2% 136,178 | 38.6% 87,376 |

| 2009 | 46.2% 121,446 | 48.5% 127,386 |

| 2005 | 42.2% 108,017 | 55.6% 142,319 |

| 2001 | 42.5% 111,221 | 55.1% 140,215 |

| 1997 | 53.3% 148,934 | 42.5% 118,834 |

| 1993 | 50.8% 157,710 | 47.4% 147,387 |

| 1989 | 39.2% 109,184 | 59.2% 165,104 |

| 1985 | 71.5% 181,238 | 27.8% 70,525 |

| 1981 | 54.1% 169,556 | 45.0% 141,018 |

| 1977 | 40.6% 111,858 | 55.8% 153,434 |

| 1973 | 34.0% 106,904 | 62.6% 196,661 |

Municipalities

editIn the last decades of the 19th century, Bergen County, to a far greater extent than any other county in the state, began dividing its townships up into incorporated boroughs; this was chiefly due to the "boroughitis" phenomenon, triggered by a number of loopholes in state laws that allowed boroughs to levy lower taxes and send more members to the county's board of freeholders. There was a 10-year period in which many of Bergen County's townships disappeared into the patchwork of boroughs that exist today, before the state laws governing municipal incorporation were changed.[38]

The county has 70 municipalities, the highest number of any county in the state, with 56 of them being boroughs.[299]

The 70 municipalities in Bergen County (with 2010 Census data for population, housing units and area) are:[300]

| Municipality (with map key) |

Municipal type |

Population | Housing Units |

Total Area |

Water Area |

Land Area |

Pop. Density |

Housing Density |

Communities[301] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allendale | borough | 6,505 | 2,388 | 3.12 | 0.02 | 3.10 | 2,100.7 | 771.2 | |

| Alpine | borough | 1,849 | 670 | 9.23 | 2.82 | 6.41 | 288.4 | 104.5 | |

| Bergenfield | borough | 26,764 | 9,200 | 2.89 | 0.01 | 2.88 | 9,306.5 | 3,199.1 | |

| Bogota | borough | 8,187 | 2,888 | 0.81 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 10,702.5 | 3,775.4 | |

| Carlstadt | borough | 6,127 | 2,495 | 4.24 | 0.24 | 4.00 | 1,532.1 | 623.9 | |

| Cliffside Park | borough | 23,594 | 10,665 | 0.96 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 24,508.7 | 11,078.5 | Grantwood (part) |

| Closter | borough | 8,373 | 2,860 | 3.30 | 0.13 | 3.16 | 2,646.0 | 903.8 | |

| Cresskill | borough | 8,573 | 3,114 | 2.07 | 0.01 | 2.06 | 4,154.5 | 1,509.0 | |

| Demarest | borough | 4,881 | 1,659 | 2.08 | 0.01 | 2.07 | 2,361.8 | 802.7 | |

| Dumont | borough | 17,479 | 6,542 | 1.99 | 0.00 | 1.98 | 8,814.7 | 3,299.2 | |

| East Rutherford | borough | 8,913 | 4,018 | 4.05 | 0.34 | 3.71 | 2,403.2 | 1,083.4 | |

| Edgewater | borough | 11,513 | 6,282 | 2.42 | 1.49 | 0.94 | 12,312.0 | 6,718.0 | |

| Elmwood Park | borough | 19,403 | 7,385 | 2.76 | 0.11 | 2.65 | 7,327.9 | 2,789.1 | |

| Emerson | borough | 7,401 | 2,552 | 2.40 | 0.20 | 2.20 | 3,358.9 | 1,158.2 | |

| Englewood | city | 27,147 | 10,695 | 4.94 | 0.02 | 4.91 | 5,524.6 | 2,176.5 | |

| Englewood Cliffs | borough | 5,281 | 1,924 | 3.33 | 1.24 | 2.09 | 2,528.1 | 921.0 | |

| Fair Lawn | borough | 32,457 | 12,266 | 5.20 | 0.06 | 5.14 | 6,315.4 | 2,386.7 | Radburn |

| Fairview | borough | 13,835 | 5,150 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 16,421.8 | 6,112.9 | |

| Fort Lee | borough | 35,345 | 17,818 | 2.89 | 0.35 | 2.54 | 13,910.9 | 7,012.7 | |

| Franklin Lakes | borough | 10,590 | 3,692 | 9.85 | 0.47 | 9.38 | 1,129.1 | 393.6 | |

| Garfield | city | 30,487 | 11,788 | 2.16 | 0.06 | 2.10 | 14,524.8 | 5,616.1 | |

| Glen Rock | borough | 11,601 | 4,016 | 2.74 | 0.02 | 2.71 | 4,275.2 | 1,480.0 | |

| Hackensack | city | 43,010 | 19,375 | 4.35 | 0.17 | 4.18 | 10,290.0 | 4,635.4 | |

| Harrington Park | borough | 4,664 | 1,624 | 2.06 | 0.23 | 1.83 | 2,545.9 | 886.5 | |

| Hasbrouck Heights | borough | 11,842 | 4,627 | 1.51 | 0.00 | 1.51 | 7,865.4 | 3,073.2 | |

| Haworth | borough | 3,382 | 1,136 | 2.36 | 0.41 | 1.94 | 1,739.2 | 584.2 | |

| Hillsdale | borough | 10,219 | 3,567 | 2.96 | 0.01 | 2.95 | 3,464.8 | 1,209.4 | |

| Ho-Ho-Kus | borough | 4,078 | 1,462 | 1.75 | 0.01 | 1.74 | 2,350.3 | 842.6 | |

| Leonia | borough | 8,937 | 3,428 | 1.63 | 0.10 | 1.54 | 5,819.5 | 2,232.2 | |

| Little Ferry | borough | 10,626 | 4,439 | 1.70 | 0.23 | 1.48 | 7,200.1 | 3,007.8 | |

| Lodi | borough | 24,136 | 10,127 | 2.29 | 0.02 | 2.26 | 10,657.6 | 4,471.7 | |

| Lyndhurst | township | 20,554 | 8,787 | 4.89 | 0.34 | 4.56 | 4,509.3 | 1,927.7 | Kingsland |

| Mahwah | township | 25,890 | 9,868 | 26.19 | 0.50 | 25.69 | 1,007.7 | 384.1 | Cragmere Park, Darlington, Fardale, Masonicus, Pulis Mills |

| Maywood | borough | 9,555 | 3,769 | 1.29 | 0.00 | 1.29 | 7,428.0 | 2,930.0 | |

| Midland Park | borough | 7,128 | 2,861 | 1.56 | 0.01 | 1.56 | 4,583.2 | 1,839.6 | Wortendyke |

| Montvale | borough | 7,844 | 2,872 | 4.01 | 0.01 | 4.00 | 1,961.2 | 718.1 | |

| Moonachie | borough | 2,708 | 1,053 | 1.68 | 0.01 | 1.66 | 1,626.5 | 632.5 | |

| New Milford | borough | 16,341 | 6,362 | 2.31 | 0.03 | 2.27 | 7,186.0 | 2,797.7 | |

| North Arlington | borough | 15,392 | 6,573 | 2.62 | 0.06 | 2.56 | 6,010.3 | 2,566.6 | |

| Northvale | borough | 4,640 | 1,635 | 1.30 | 0.00 | 1.30 | 3,582.3 | 1,262.3 | |

| Norwood | borough | 5,711 | 2,007 | 2.73 | 0.01 | 2.73 | 2,093.5 | 735.7 | |

| Oakland | borough | 12,754 | 4,470 | 8.73 | 0.27 | 8.45 | 1,508.6 | 528.7 | |

| Old Tappan | borough | 5,750 | 1,995 | 4.20 | 0.87 | 3.33 | 1,725.8 | 598.8 | |

| Oradell | borough | 7,978 | 2,831 | 2.58 | 0.15 | 2.42 | 3,291.5 | 1,168.0 | |

| Palisades Park | borough | 19,622 | 7,362 | 1.28 | 0.02 | 1.25 | 15,681.6 | 5,883.6 | |

| Paramus | borough | 26,342 | 8,915 | 10.52 | 0.05 | 10.47 | 2,516.0 | 851.5 | Arcola |

| Park Ridge | borough | 8,645 | 3,428 | 2.60 | 0.02 | 2.58 | 3,348.6 | 1,327.8 | |

| Ramsey | borough | 14,473 | 5,550 | 5.59 | 0.07 | 5.52 | 2,621.9 | 1,005.4 | |

| Ridgefield | borough | 11,032 | 4,145 | 2.85 | 0.30 | 2.55 | 4,323.7 | 1,624.5 | Grantwood (part) |

| Ridgefield Park | village | 12,729 | 5,164 | 1.92 | 0.20 | 1.72 | 7,385.6 | 2,996.2 | |

| Ridgewood | village | 24,958 | 8,743 | 5.82 | 0.07 | 5.75 | 4,339.0 | 1,520.0 | |

| River Edge | borough | 11,340 | 4,261 | 1.90 | 0.04 | 1.85 | 6,116.3 | 2,298.2 | |

| River Vale | township | 9,659 | 3,521 | 4.28 | 0.26 | 4.01 | 2,408.1 | 877.8 | |

| Rochelle Park | township | 5,530 | 2,170 | 1.06 | 0.02 | 1.04 | 5,313.8 | 2,085.2 | |

| Rockleigh | borough | 531 | 86 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.97 | 548.1 | 88.8 | |

| Rutherford | borough | 18,061 | 7,278 | 2.94 | 0.14 | 2.81 | 6,437.4 | 2,594.1 | |

| Saddle Brook | township | 13,659 | 5,485 | 2.72 | 0.03 | 2.69 | 5,080.2 | 2,040.0 | |

| Saddle River | borough | 3,152 | 1,341 | 4.98 | 0.06 | 4.92 | 640.2 | 272.4 | |

| South Hackensack | township | 2,378 | 879 | 0.74 | 0.02 | 0.72 | 3,311.7 | 1,224.1 | |

| Teaneck | township | 39,776 | 14,024 | 6.23 | 0.22 | 6.01 | 6,622.2 | 2,334.8 | |

| Tenafly | borough | 14,488 | 4,980 | 5.18 | 0.58 | 4.60 | 3,148.6 | 1,082.3 | |

| Teterboro | borough | 67 | 27 | 1.16 | 0.00 | 1.16 | 57.9 | 23.3 | |

| Upper Saddle River | borough | 8,208 | 2,776 | 5.28 | 0.02 | 5.26 | 1,560.0 | 527.6 | |

| Waldwick | borough | 9,625 | 3,537 | 2.09 | 0.02 | 2.07 | 4,656.8 | 1,711.3 | |

| Wallington | borough | 11,335 | 4,946 | 1.03 | 0.05 | 0.98 | 11,528.6 | 5,030.5 | |

| Washington Township | township | 9,102 | 3,341 | 2.96 | 0.05 | 2.91 | 3,128.8 | 1,148.5 | |

| Westwood | borough | 10,908 | 4,636 | 2.31 | 0.05 | 2.27 | 4,814.5 | 2,046.2 | |

| Woodcliff Lake | borough | 5,730 | 1,980 | 3.61 | 0.20 | 3.41 | 1,682.7 | 581.5 | |

| Wood-Ridge | borough | 7,626 | 3,051 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 6,951.6 | 2,781.2 | |

| Wyckoff | township | 16,696 | 5,827 | 6.61 | 0.06 | 6.55 | 2,550.1 | 890.0 | |

| Bergen County | county | 905,116 | 352,388 | 246.67 | 13.66 | 233.01 | 3,884.5 | 1,512.3 |

Historical municipalities

editOver the history of the county, there have been various municipality secessions, annexations and renamings. The following is a partial list of former municipalities, ordered by year of incorporation.[31]

|

|

Economy

editThe Bureau of Economic Analysis calculated that the county's gross domestic product was $81.5 billion in 2022, which was ranked first in the state and was a 1.2% increase from the prior year.[302]

Largest employers

editAccording to the Bergen County Economic Development Corporation, the largest employers in Bergen County as of November 2012, as ranked with at least 1,000 employees in the county, were as follows:[303]

- Hackensack University Medical Center, Hackensack, 8,000

- Valley Health System, Ridgewood, 4,660

- Bio-Reference Laboratories, Inc., Elmwood Park, 2,900

- Medco Health Solutions, Franklin Lakes, 2,800 (no longer an independent company)

- County of Bergen, Hackensack, 2,390

- Quest Diagnostics, Teterboro/Lyndhurst, 2,200

- KPMG, Montvale, 2,100

- Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, 2,002

- Englewood Hospital Home Health Care Services, Englewood, 1,985

- Unilever Bestfoods, Englewood Cliffs, 1,900

- Stryker Corporation, Allendale/Mahwah, 1,812

- Bergen Regional Medical Center, Paramus, 1,746

- Holy Name Medical Center, Teaneck, 1,695

- Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, 1,500

- Crestron Electronics, Rockleigh/Cresskill, 1,500

- BMW of North America, Woodcliff Lake, 1,000

In January 2015, Mercedes-Benz USA announced that it would be moving its headquarters from the borough of Montvale in Bergen County to the Atlanta, Georgia, area as of July. The company had been based in northern New Jersey since 1972 and has had 1,000 employees on a 37-acre (15 ha) campus in Montvale. Despite incentive offers from the State of New Jersey to remain in Bergen County, Mercedes-Benz cited proximity to its Alabama manufacturing facility and a growing customer base in the southeastern United States, in addition to as much as $50 million in tax incentives from Georgia governmental agencies, in explaining its decision to move. However, Mercedes-Benz USA also stated its intent to maintain its Northeast regional headquarters in Montvale and to build a "state-of-the-art" assemblage training center in the borough as well.[304]

Building permits

editIn 2011, Bergen County issued 1,903 new building permits for residential construction, the largest number in New Jersey.[305]

Retail

editThe retail industry, anchored in Paramus, is a mainstay of the Bergen County economy, with a combined payroll of $1.7 billion as of 2012.[306] The largest retail entities are described below in further detail:

Garden State Plaza

editThe Garden State Plaza megamall is located in Paramus. The mall is owned and managed by Paris-based real estate management company Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield, and located at the intersection of Route 4 and Route 17 near the Garden State Parkway, about 15 miles (24 km) west of Manhattan.[309] Opened in 1957 as the first suburban shopping mall in New Jersey,[310][311] it contains 2,118,718 sq ft (196,835.3 m2) of leasable space,[312][313] and housing over 300 stores,[309] it is the second-largest mall in New Jersey, the third-largest mall in the New York metropolitan area, and one of the highest-revenue producing malls in the United States.[314]

American Dream Meadowlands

editAmerican Dream, located 8 miles (13 km) south of Garden State Plaza, is another large retail and entertainment complex, situated in the Meadowlands Sports Complex in East Rutherford.[315] The first and second of four opening stages occurred on October 25, 2019, and on December 5, 2019.[316][317] The remaining opening stages occurred on October 1, 2020, and thereafter.[318] As of January 2023, the megamall hosts over 200 stores and other commercial establishments.

Blue laws