Bellefontaine (/bɛlˈfaʊntən/ bel-FOWN-tən[5]) is a city in, and the county seat of, Logan County, Ohio, United States,[6] located 48 miles (77 km) northwest of Columbus. The population was 14,115 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Bellefontaine micropolitan area, which includes all of Logan County. The highest point in Ohio, Campbell Hill, is within the city limits.

Bellefontaine, Ohio | |

|---|---|

Logan County courthouse in Bellefontaine | |

| Nickname: The Peak of Ohio | |

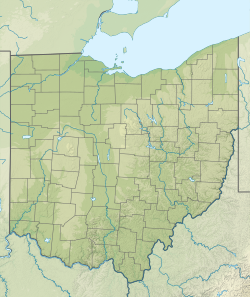

Detailed map of Bellefontaine | |

| Coordinates: 40°22′10″N 83°45′18″W / 40.36944°N 83.75500°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Logan |

| Founded | 1817 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | David Crissman (R)[citation needed] |

| Area | |

• Total | 10.10 sq mi (26.17 km2) |

| • Land | 10.10 sq mi (26.17 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,240 ft (380 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 14,115 |

• Estimate (2023)[3] | 14,073 |

| • Density | 1,397.11/sq mi (539.42/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 43311 |

| Area codes | 937, 326 |

| FIPS code | 39-05130[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2394116[2] |

| Website | ci.bellefontaine.oh.us |

History

editThe name Bellefontaine means "beautiful spring" in French, and is purported to refer to several springs in the area.[7] However, locally, the original French pronunciation is not used, and it is pronounced "bell fountain."

Blue Jacket's Town

editAround 1777, the Shawnee war chief Blue Jacket (Weyapiersenwah) built a settlement here, known as "Blue Jacket's Town". Blue Jacket and his band had previously occupied a village along the Scioto River, but the American Revolutionary War had reached the Ohio Country. Blue Jacket and other American Indians who took up arms against the American revolutionaries relocated in order to be closer to their British allies at Detroit.

After the United States gained independence, its forces continued warfare against former Indian allies of the British. Blue Jacket's Town was destroyed in Logan's Raid, conducted by Kentucky militia in 1786 at the outset of the Northwest Indian War. The expedition was led by Benjamin Logan, namesake of Logan County. Blue Jacket and his followers relocated further northwest to the Maumee River.[8]

Beginning in the 1800s, American Revolutionary War veterans and others from Virginia and elsewhere began settling in the area of Blue Jacket's Town. Bellefontaine is on or near the edge of the Virginia Military District, where the cash-poor government granted tracts of land to veterans in payment for their services during the war. The Treaty of Greenville defined lands to be held by European Americans as separate from those to be held by natives but it was poorly administered in the area and whites frequently encroached on native lands.[8]

Railroads

editBellefontaine was platted by European Americans in 1820 and incorporated by the legislature in 1835.[9][10][11] In 1837, the Mad River & Lake Erie Railroad built the first railroad to Bellefontaine. This began its reputation as a railroading town. In the 1890s the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway (also called the Big Four Railroad) built a main terminal in the city. This terminal boasted the largest roundhouse between New York and St. Louis.[12]

Though railroading hit hard times and the industry went through radical restructuring in the late 20th century, and the Big Four terminal ceased operations in 1983, Bellefontaine remains a landmark on America's railways. The city is now just a thoroughfare for CSX.

Automotive transportation

editIn 1891, Bellefontaine became the location of the first concrete street in America. George Bartholomew invented a process for paving using Portland cement, which until then had been used in stone construction. A small section of Main Street, on the west side of the Logan County Courthouse, was the first to be paved using that process. When that proved successful, Court Avenue, which runs along the south side of the courthouse, was paved with concrete. While Main Street is now paved with asphalt, Court Avenue has retained its original concrete pavement for more than 100 years. At its centennial, the street was closed to vehicular traffic and a statue of Bartholomew placed at its Main Street end; it became a pedestrian way. Since then one lane has been reopened for eastbound traffic.

In 1979, Honda began manufacturing motorcycles in the nearby city of Marysville, Ohio. Since that time, Honda's operations in the Bellefontaine area have greatly expanded. Bellefontaine is a central location among Honda operations in Marysville, East Liberty, Russells Point, Anna, and Troy, Ohio. Honda is Bellefontaine's largest employer in the early 21st century.

U.S. Route 68 intersects with State Routes 47 and 540 in Bellefontaine. U.S. Route 33, a freeway that has interchanges with US 68 and SR 540, skirts the northern edge of the city.

Campbell Hill

editTo European settlers, Campbell Hill was first known as Hogue's Hill, perhaps a misspelling of Solomon Hoge's surname, the person who first deeded the land in 1830. In 1898, the land was sold to Charles D. Campbell, in whose name Campbell Hill is now known. Campbell sold the hill and surrounding land to August Wagner.

In 1950, the family of August Wagner deeded Campbell Hill and the surrounding 57.5 acres to the U.S. government. The government stationed the 664th Aircraft Control and Warning Squadron on the hill in 1951. This military unit was responsible for monitoring for possible aerospace attacks from the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The 664th AC&WS and similar military units were eventually superseded by the North American Aerospace Defense Command (or NORAD). The base in Bellefontaine was closed in 1969.

The Ohio Hi-Point Vocational-Technical District opened a school atop the hill in 1974. The school is now known as the Ohio Hi-Point Career Center.

Revitalization

editIn 2012 local real estate developer Small Nation purchased and renovated the former J.C. Penney building. Since then, the organization invested over $33 million in renovating over 56 downtown buildings and attracting new businesses to the area.[13][14] The investment into the properties created roughly 200 jobs in the city.[14] In 2018, Bellefontaine was classified as an Opportunity Zone to further attract investors to the area.[15] Neighboring areas have begun using Bellefontaine as a model to attract more investment in their own towns.[16]

In 2022, Bellefontaine was named one of Ohio's Best Hometowns by Ohio Magazine for its downtown redevelopment efforts, thriving sense of community and appreciation for preserving local history.[17]

In 2022, Bellefontaine's Christmas parade included a drag queen and over 60 residents opposed their appearance at a City Council meeting,[18] prompting drag queens and supporters attending a later council meeting in support.[19] In 2023, the opposing residents began pushing for a city ordinance that would classify drag performances as ‘adult entertainment,' making it one of the first municipalities in Ohio to do so.[20] The Ohio Supreme Court unanimously ruled to remove the measure from the ballot when petitioners changed the ballot language after circulating petitions.[21]

Geography

editAccording to the 2010 census, the city has a total area of 10.04 square miles (26.0 km2), all land.[22]

Climate

editThe city of Bellefontaine is at the convergence of the humid subtropical (Köppen Cfa) and humid continental (Köppen Dfa) climate zones according to the Köppen climate map. The region is characterized by four distinct seasons. Winters are cool to cold with mild periods, and summers are generally hot and muggy, with significant precipitation year-round. The city is too far south to experience lake effect snow from the Great Lakes region, however it does experience more snow than surrounding areas due to the city's elevation. Traditionally, Bellefontaine's elevation excludes it from tornadoes and floods that affect the majority of the Miami Valley.

| Climate data for Bellefontaine, Ohio, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1894–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

72 (22) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

97 (36) |

101 (38) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

98 (37) |

90 (32) |

80 (27) |

71 (22) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 57.0 (13.9) |

60.5 (15.8) |

69.8 (21.0) |

78.6 (25.9) |

85.8 (29.9) |

90.7 (32.6) |

90.7 (32.6) |

89.4 (31.9) |

88.5 (31.4) |

81.3 (27.4) |

68.2 (20.1) |

59.7 (15.4) |

92.4 (33.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 33.5 (0.8) |

37.1 (2.8) |

47.5 (8.6) |

60.7 (15.9) |

71.3 (21.8) |

79.5 (26.4) |

82.6 (28.1) |

81.3 (27.4) |

76.0 (24.4) |

63.7 (17.6) |

49.9 (9.9) |

38.4 (3.6) |

60.1 (15.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 25.5 (−3.6) |

28.4 (−2.0) |

38.0 (3.3) |

49.8 (9.9) |

60.9 (16.1) |

69.7 (20.9) |

72.8 (22.7) |

71.4 (21.9) |

65.2 (18.4) |

53.1 (11.7) |

41.0 (5.0) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

50.6 (10.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 17.6 (−8.0) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

38.8 (3.8) |

50.6 (10.3) |

59.9 (15.5) |

63.0 (17.2) |

61.5 (16.4) |

54.4 (12.4) |

42.5 (5.8) |

32.1 (0.1) |

23.6 (−4.7) |

41.0 (5.0) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −4.4 (−20.2) |

1.3 (−17.1) |

10.0 (−12.2) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

35.5 (1.9) |

45.8 (7.7) |

52.5 (11.4) |

50.5 (10.3) |

40.5 (4.7) |

28.4 (−2.0) |

17.5 (−8.1) |

5.1 (−14.9) |

−7.7 (−22.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −27 (−33) |

−21 (−29) |

−12 (−24) |

9 (−13) |

23 (−5) |

34 (1) |

41 (5) |

38 (3) |

25 (−4) |

11 (−12) |

−6 (−21) |

−22 (−30) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.04 (77) |

2.46 (62) |

3.20 (81) |

4.11 (104) |

4.31 (109) |

4.96 (126) |

4.45 (113) |

3.90 (99) |

3.18 (81) |

2.82 (72) |

3.13 (80) |

3.08 (78) |

42.64 (1,082) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 14.5 | 12.1 | 12.7 | 13.4 | 13.6 | 12.5 | 10.6 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 13.1 | 141.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA[23] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[24] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 170 | — | |

| 1830 | 266 | 56.5% | |

| 1840 | 475 | 78.6% | |

| 1850 | 1,222 | 157.3% | |

| 1860 | 2,599 | 112.7% | |

| 1870 | 3,182 | 22.4% | |

| 1880 | 3,998 | 25.6% | |

| 1890 | 4,245 | 6.2% | |

| 1900 | 6,649 | 56.6% | |

| 1910 | 8,238 | 23.9% | |

| 1920 | 9,336 | 13.3% | |

| 1930 | 9,543 | 2.2% | |

| 1940 | 9,808 | 2.8% | |

| 1950 | 10,232 | 4.3% | |

| 1960 | 11,424 | 11.6% | |

| 1970 | 11,255 | −1.5% | |

| 1980 | 11,798 | 4.8% | |

| 1990 | 12,142 | 2.9% | |

| 2000 | 13,069 | 7.6% | |

| 2010 | 13,370 | 2.3% | |

| 2020 | 14,115 | 5.6% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 14,073 | [3] | −0.3% |

| Sources:[4][25][26] | |||

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 13,069 people, 5,319 households, and 3,436 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,491.3 inhabitants per square mile (575.8/km2). There were 5,722 housing units at an average density of 652.9 per square mile (252.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 90.82% White, 5.13% African American, 0.15% Native American, 0.93% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.53% from other races, and 2.40% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.12% of the population.

There were 5,319 households, of which 34.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.7% were married couples living together, 14.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.4% were non-families. 30.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.43 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the city the population was spread out, with 28.1% under the age of 18, 10.0% from 18 to 24, 29.1% from 25 to 44, 19.9% from 45 to 64, and 12.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $37,189, and the median income for a family was $43,778. The per capita income for the city was $20,917. About 19.9% of families and 23.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 38.9% of those under the age of 18 and 10.9% of those ages 65 and older.

2010 census

editAs of the census[27] of 2010, there were 13,370 people, 5,415 households, and 3,420 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,331.7 inhabitants per square mile (514.2/km2). There were 6,115 housing units at an average density of 609.1 per square mile (235.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 90.1% White, 4.3% African American, 0.2% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0.5% from other races, and 3.7% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.9% of the population.

There were 5,415 households, of which 35.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.1% were married couples living together, 15.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 6.1% had a male householder with no wife present, and 36.8% were non-families. 30.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 3.01.

The median age in the city was 34.8 years. 27.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 9.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.3% were from 25 to 44; 24.7% were from 45 to 64; and 12.8% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.4% male and 51.6% female.

Micropolitan statistical area

editBellefontaine is the center of the Bellefontaine Micropolitan Statistical Area, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. This micropolis consists solely of Logan County, Ohio. The 2000 census[4] found 46,005 people in the micropolis, making it the 260th most populous such area in the United States. Among all U.S. statistical areas (CBSAs), the Bellefontaine micropolis ranks 622nd. In Ohio, the Bellefontaine micropolis is the 37th most populous CBSA, and the 21st most populous micropolitan statistical area.

By comparison, the least populous metropolitan area in the United States, Carson City, Nevada, has 52,457 residents. The least populous metropolitan area in Ohio is Sandusky, with 79,555 residents. The Bellefontaine micropolis is not as populous as these, but does have a greater population than some micropolitan statistical areas traditionally considered to be small regional cities. (Examples: El Dorado, Arkansas; Clovis, New Mexico; and Red Wing, Minnesota.)

Though official definitions of micropolitan statistical areas did not exist until 2003, the area now constituting the Bellefontaine micropolis grew in population by 8.7 percent between 1990 and 2000.

Government

editBellefontaine has an elected mayor and city council style of government.

Local

edit- Mayor David A. Crissman (R) [28]

City Council

editBellefontaine City Council Members serve 2 year terms. The city has 4 wards and 3 At-Large seats.[29]

| Position/Ward | Name | Party |

|---|---|---|

| President | Zebulon Wagner | R |

| 1 | John G. Aler | R |

| 2 | Jordan Reser | R |

| 3 | Nick Davis | R |

| 4 | MacKenzie Meyers Fitzpatrick | D |

| At-Large | Deborah E. Baker | R |

| At-Large | Jenna James | R |

| At-Large | Kyle Springs | R |

Arts and culture

editSites of interest

edit- McKinley Street — Whether or not this is the shortest street in the world is a point of contention. The sign at the street's south end (at the intersection of Columbus Ave.) once made such a claim, although Ebenezer Place, in Wick, Scotland, has held the official record since November 2006.[30] The City of Bellefontaine's website places the length of McKinley Street at "about 20 feet", and while the city's website does not make the claim of the world's shortest street, it does cite McKinley Street as "the shortest street in America". The street sign's undersign reads "Shortest Street In America" as of May 2, 2020.

- Court Avenue - A small street in downtown, located adjacent to the Logan County Courthouse. It is known for being the first street in the United States to be paved with concrete.[31]

- Holland Theater - This theater is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It opened in the 1930s as a live theater, but was later converted to a 5-screen megaplex before closing in 1998. In recent years, it has been reopened for live events and performances serving Bellefontaine and the surrounding area. In 2019, after extensive renovations lasting about a year, The Holland Theater was reopened for performances.

- Campbell Hill, the highest elevated point in Ohio.

- The first brokerage house of Edward D. Jones houses an office of the brokerage he started.

- First United Methodist Church, where preacher Norman Vincent Peale got his start.

Logan County Historical Society

editThe Logan County Historical Society and museum was first housed in the McBeth School, built in 1919 as the last of the four elementary schools to be built in Bellefontaine at the turn of the century. The building was sold at public auction in 1957 to the Church of God. In 1971 McBeth School was purchased by the Logan County Historical Society for use as the Logan County Historical Museum. The historical society eventually grew out of the 3-story building and moved to its current home closer to Downtown. McBeth School has been adapted for use as an apartment building.[32]

Today the museum includes the Orr mansion, former home of the local Orr family; as well as an extension to the mansion that includes history exhibits from around the county. The Mansion portion of the building has been completely restored by the historical society. Day-to-day operations in the museum and The Logan County Historical Society are supported by a Logan County tax levy and donations received from visitors to the museum.

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editThe Bellefontaine Regional Airport is located about 5 miles from the downtown business district. The airport replaced the Bellefontaine Municipal Airport in 2002 and is one of 2 new airports opened to the public in Ohio in the past 30 years.[33]

U.S. 68 passes north-south through Bellefontaine. U.S. 33 passes through the north side of Bellefontaine. Ohio State Route 47 passes through the city.

Bellefontaine had been part of the New York Central Railroad's St. Louis - Indianapolis - Cleveland corridor of passenger trains.[34] Up to 1966, the New York Central ran the Southwestern Limited (St. Louis - New York City via Cleveland) through Bellefontaine. The city was also a crossing point for the New York Central's Detroit - Cincinnati trains. The last of these (Ohio Special southbound, Michigan Special northbound) ended in 1958 or 1959.[35] The final train running through Bellefontaine, the Penn Central's Indianapolis - Cleveland remnant of the Southwestern Limited, ended in 1971, upon Amtrak taking up private companies' long distance passenger operations.

Education

editThe Bellefontaine City Schools operate one elementary school, one intermediate school, one middle school, and one high school in the area.[36] These schools have a combined enrollment of 2,840. In addition, the Ohio Hi-Point Career Center, located atop Campbell Hill, offers both secondary and post-secondary education. Enrolled at Ohio Hi-Point are 505 students. The neighboring Benjamin Logan Local School District campus also has a Bellefontaine address.

Several colleges and universities operate satellite campuses in the Bellefontaine area. These include:

Bellefontaine has a public library, a branch of Logan County Libraries.[37]

Media

editThe city is served by both print publishing and radio broadcasting.

The Bellefontaine Examiner is the daily local newspaper. It is the latest in a series of newspapers which have been published in Bellefontaine since 1831. It has a current daily circulation of approximately 9500 copies.[38]

Operating currently are WPKO, an FM radio station, WPKO HD2, a second FM radio station, and its sister station WBLL, an AM radio station. These stations are owned and operated by V-Teck Communications.[39]

Two Christian radio stations WKEN, an FM radio station operating on FM frequency of 88.5 and WSOH, an FM radio station operating on FM frequency of 88.9. These stations are owned and operated by Soaring Eagle Promotions, Inc.[40]

Notable people

edit- Matthew Anderson - member of the Wisconsin State Assembly and the Wisconsin State Senate

- George Bartholomew - inventor

- Sami Callihan - professional wrestler

- Julius Chambers - journalist and travel writer

- Bethany Dillon - singer

- Allan W. Eckert - author

- Jim Flora - artist

- Melville J. Herskovits - anthropologist

- Livingston Hopkins - cartoonist

- Kin Hubbard - cartoonist and journalist

- Blue Jacket "Weyapiersenwah" - Shawnee chief

- Edward D. Jones - investment banker

- Austin Eldon Knowlton - architect

- William Lawrence - politician (Republican)

- The Mills Brothers - singing group, spent their youth here.

- Don Otten - professional basketball player

- Virginia Sharpe Patterson - writer

- Norman Vincent Peale - minister and author

- Frederick Plum - 1920 olympian

- Ralph Lane Polk - publisher

- Ed Ratleff - professional basketball player

- Louie Vito - Olympic snowboarder

- Samuel D. Wonders - Engineer and businessman

References

edit- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Bellefontaine, Ohio

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Ohio: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "E.W. Scripps School of Journalism Ohio Pronunciation Guide | Ohio University". www.ohio.edu. Ohio University. 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Ohio History Central

- ^ a b Ohio History, Vol. 12, pg 169 Archived 2009-04-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ History of Bellefontaine Archived 2004-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, City of Bellefontaine. Accessed 2009-10-31.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Bellefontaine, Ohio

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Trostel, Scott D. (2005). The Columbus Avenue Miracle: Bellefontaine, Ohio's WW II Serviceman's Free Canteen. Cam-Tech Publishing. ISBN 0-925436-50-X.

- ^ "Downtown Bellefontaine nominated for HGTV series". Peak of Ohio. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ a b STAFF, BELLEFONTAINE EXAMINER (February 29, 2020). "Thinking small yields big downtown expansion". Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Opportunity Zone | Logan County Chamber of Commerce". www.logancountyohio.com. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ Sanctis, Matt. "Urbana looks to Bellefontaine as model of redevelopment". springfield-news-sun. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ Shiffler, Matt. "Best Hometowns 2022: Bellefontaine". www.ohiomagazine.com. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "Christmas parade dominates public comments". Peak of Ohio. January 24, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ Schneck, Ken (January 25, 2023). "Ohioans show up in force to address city council to argue for drag queen, inclusion in holiday parade". The Buckeye Flame. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ Kendall, Crawford (June 14, 2023). "Bellefontaine's debate around drag queens". WOSU News. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Election 2023: Ohio Supreme Court scraps proposed drag show ban from city's ballot". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "2010 Census U.S. Gazetteer Files for Places – Ohio". United States Census. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Bellefontaine, OH". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Cincinnati". National Weather Service. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ "Number of Inhabitants: Ohio" (PDF). 18th Census of the United States. U.S. Census Bureau. 1960. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Ohio: Population and Housing Unit Counts" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ "City of Bellefontaine Elected Officials 2024" (PDF). Logan County Board of Elections. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ "City of Bellefontaine Elected Officials 2024" (PDF). Logan County Board of Elections. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ "Street measures up to new record". BBC News. November 1, 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Cracked street's hereafter splits Bellefontaine Archived 2011-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, The Columbus Dispatch, 2008-06-01. Accessed 2008-10-10.

- ^ "Logan County Historical Society," Published History of Logan County, 1982

- ^ "AOPA's Boyer takes part in Ohio airport grand opening" (Press release). Aircraft owners and Pilots Association (USA). August 16, 2002. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ New York Central timetable, Tables 3, 4, 18, 19 https://streamlinermemories.info/NYC/NYC47-12TT.pdf

- ^ New York Central timetable, October 1958, Table 24

- ^ "Bellefontaine City Schools". Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- ^ "Branches". Logan County Libraries. April 9, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "Echo Media V3 Print Media Experts".

- ^ "FM Query Results -- Audio Division (FCC) USA".

- ^ "FM Query Results -- Audio Division (FCC) USA". transition.fcc.gov. Retrieved November 28, 2017.