This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

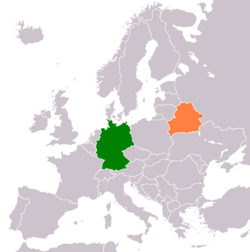

Germany has an embassy in Minsk. Belarus has an embassy in Berlin, a consulate general in Munich, and two honorary consulates in Cottbus and Hamburg.

| |

Belarus |

Germany |

|---|---|

History

editIn the Battle of Tannenberg (1410), the Teutonic Order was defeated by the forces of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Lithuania at that time included the Belarusian territories, so the Lithuanian army at that time also consisted of Belarusian contingents.[citation needed]

World War I

editSince the partitions of Poland (1772, 1793 and 1795) and thus also during the First World War, the Belarusian territories were part of the Russian Empire, so the Belarusians fought on the side of the Triple-Entente. On February 25, 1918, German troops entered Minsk. On March 3, 1918, the Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaty was signed in the city of Brest between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers. The treaty eliminated Soviet Russia as a participant in the war.

Under German protection, but without the consent of the occupying power, independence was proclaimed for the first time on March 25, 1918.[citation needed] The "Rada", the executive body of the First Belarusian People's Congress, declared the secession from Soviet Russia and proclaimed the "free and independent Belarusian People's Republic", which was recognized neither by the German Empire nor by the Western powers. However, the Rada thanked Kaiser Wilhelm II in a telegram for the occupation of Belarus and emphasized that it saw a good fate for its people in the future only under the protectorate of the German state.[1] The Belarusian People's Republic existed only for half a year until the autumn of 1918, but historically and in the consciousness of Belarusians it is considered the founding act of a separate Belarusian statehood.[citation needed] The Rada is still active today as a government in exile.

In the wake of the German Revolution of 1918–1919, the lapse of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and the civil war in neighboring Russia, which also spread to Belarus, the eastern part of the country came under the control of the Communists. The western part of the present Belarusian territory formed the eastern part of the then Poland.

World War II

editOn September 17, 1939, the Red Army occupied eastern Poland. In the secret additional protocol of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact, the territories between Slutsch and Bug (i.e. the whole of Belarus) were assigned to the Soviet sphere of interest. From 1940 in Berlin the periodical Ranica - Der Morgen. Weißruthenische Zeitung in Deutschland, which was aimed specifically at Belarusian emigrants, was published in Berlin and promoted by the SS. It was aimed at Belarusians living in Germany and attempted to recruit them for the Waffen SS.[2] In the summer of 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa) and the German Wehrmacht conquered Belarus within a few weeks in the course of the Kesselschlacht near Białystok and Minsk. During the invasion, the Red Army evacuated about 20% of the Belarusian population to Russia and destroyed the food supply.[3]

The German invasion brought severe destruction. Although people in many areas of Belarus were initially happy about the Soviet defeat, the Germans quickly disappointed the local population. From 1941 to 1944, the Wehrmacht and SS murdered some two and a half million Belarusians-more than a quarter of the population. The German soldiers waged a war of annihilation against the civilian population. More than 200 towns and 9000 villages were destroyed. In many cases the German soldiers drove the villagers into barns and burned them down, as in 1943 in Khatyn (not to be confused with Katyn). Today, this place near Minsk is a memorial to the victims of World War II. In Minsk alone, the German occupation forces murdered more than 100,000 inhabitants.[citation needed] The Jewish population of Belarus was almost completely murdered. About eight to nine percent of all European Jews who were killed in the Holocaust were from Belarus. Almost all cities in the country were completely destroyed. Industrial enterprises had decreased by 85 percent, industrial capacity by 95 percent, seeded land by 40 to 50 percent, livestock by 80 percent. There were three million homeless people after the end of the war. Furthermore, a large part of the ethnic Poles (about 300,000) were forcibly resettled in the German eastern territories that had been annexed to Poland.[citation needed] Before World War II, ten million people lived in Belarus. It was not until the late 1980s that the population had returned to its pre-war level.[citation needed]

During World War II, the term White Ruthenia (German: Weißruthenien) was used in German, reflecting the efforts of the Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories, Alfred Rosenberg, to distinguish the Belarusians as much as possible from the Great Russians. Although, in Belarusian, the term used was Belarus (Belarusian: Беларусь).[4]

During the German occupation, the Belarusian Central Council was installed in Belarus, a puppet government that used historic Belarusian state emblems. The chairman of the BCR was Radasłaŭ Astroŭski. This "government" disappeared after the withdrawal of the German Eastern Front in 1944. On March 25, 1948, the Belarusian Central Council was re-established as a government-in-exile in Germany, competing with the Rada BNR.[5] Other institutions such as the Belarusian Home Guard, the Belarusian Self-Defense Corps, the Belarusian Auxiliary Police, the Belarusian Youth Organization, and the Belarusian Self-Help Organization were also founded. The Belarusian Independence Party (BNP) collaborated with the German occupiers with the aim of establishing a Belarusian nation-state.[citation needed]

The armed resistance movement of Belarus was considered one of the strongest in Europe.[citation needed] There were over 1000 partisan groups, which were mostly communist, but also nationalist oriented. At the beginning of 1943, the repatriation of about 10,500 Germans from the territory of the so-called Army Group Central and from Belarus began.[citation needed] These ethnic Germans were resettled in the Warthegau (in occupied Poland) and the then German Reich. In the fall of 1943, the Red Army recaptured the far east of the country, and by the summer of 1944, the entire country had been recaptured.

Postwar period

editAfter the Second World War, thousands of Belarusians came to Germany for various reasons. In 1945, there were an estimated 400,000 to 500,000 Belarusians on German or Austrian territory.[citation needed] Belarusian national committees were established in Regensburg, Munich and Braunschweig. Belarusian DP camps were located in Watenstedt, Osterhofen and in the Ganghofer suburb of Regensburg. Belarusians were particularly active culturally in the camp for displaced persons in Michelsdorf in Upper Palatinate. Between 1946 and 1950, the emigrants in Michelsdorf ran their own Belarusian-language high school, which at times had 122 students and was named after the national poet Yanka Kupala. In 1949 the school was moved to Backnang, where it existed until February 1950.[6]

On December 29, 1947, at a meeting in a DP camp in Osterhofen, it was decided to reactivate the Rada of the Belarusian People's Republic under the leadership of Mikola Abramchyk. At that time, the Rada comprised 72 members.[7]

In Mittenwald in Upper Bavaria, east of the Luttensee barracks, there is a memorial to Belarusian prisoners of war.[citation needed] In 1948, the former prisoners of war or displaced persons used it to honor the participants of the Slutsk uprising, an anti-Bolshevik uprising in 1920.[citation needed]

Independent Belarus

editAfter the collapse of the Soviet Union, relations between Belarus and Germany initially developed positively. Diplomatic relations were established in 1992. However, a turn for the worse was initiated in 1994, when Alexander Lukashenko was elected president. He immediately took action against a press that was politically and economically oriented toward the West and repeatedly denounced the financial transfers of political organizations - including the German Friedrich Ebert Foundation - to friendly organizations and media in Belarus.[citation needed] As a result of human rights violations and dissonance regarding the opening of the country to a market economy, the administration of the European Union, with the participation of Germany, imposed an entry ban on the Belarusian government in 1997. On May 18, 2006, the European Union (again including Germany) decided to freeze the accounts of President Lukashenko and 35 other government officials.[citation needed]

Security cooperation existed between the Federal Republic of Germany and Belarus from 2008 until at least 2011, with Lukashenko's security forces receiving training in Germany.[citation needed] Nearly 400 border guards, senior militia officers, and forensic technicians were also trained by German officials directly in Belarus, and in 2010, Belarusian security forces observed German police officers on duty for several days during the transport of Atomic waste to Gorleben in Lower Saxony.[citation needed] As the EU identified improvements in the country's human rights record in 2015 and 2016, much of the sanctions were gradually lifted following the 2015 presidential election in Belarus. [citation needed]

As a result of the 2020–2021 Belarusian protests against Lukashenko's dictatorial rule, the Belarusian community "RAZAM" e.V., the first interest group of and for people with a Belarusian background living in Germany, was founded in August 2020.[8] In the course of the protests, German Chancellor Angela Merkel declared that she was on the side of the peaceful demonstrators. The results of the 2020 presidential election in Belarus would not be recognized because of cases of electoral fraud. Merkel also said she had tried in vain to reach Belarusian President Lukashenko by phone in August 2020.[9] The European Union no longer recognizes Lukashenko as a legitimate head of state.[10]

Belarusian support for the Russian invasion of Ukraine has further deteriorated bilateral relations. The European Union imposed further sanctions on Belarus and trade between Belarus and Germany declined.[11]

On June 24, 2024, German citizen Rico Krieger was sentenced to death for six criminal offenses in a secret trial in Minsk. Among other things, he was accused of "terroris" and "mercenarism". According to the human rights organization Viasna, the conviction is directly linked to the Kastuś Kalinoŭski Regiment, a unit of Belarusian volunteers fighting for Ukraine. However, the regiment stated that Krieger was not part of their unit.[12] On July 30, Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko pardoned him after he had applied for clemency.[13]

Economic relations

editBelarus was an important transit country between Central Europe and Russia due to its location: 50% of Russian crude oil flows through the Druzhba pipeline ending in Schwedt/Oder, which is serviced on Belarusian territory by the company Gomel Transneft. However, due to the political situation in Belarus, Russia is increasingly turning to northern Europe. In 2005, tconstruction of the Nord Stream pipeline through the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany began and was completed in 2011 making Russia's gas supplies to Western Europe less dependent on Belarus.

In 2014, only trade with Russia and Ukraine was more important for Belarus than trade with Germany. This amounted to approx. 4 billion US dollars. The representative office of German business in the Republic of Belarus (the Chamber of Commerce Abroad) exists in Minsk.[14] In 2021, Germany was Belarus' fifth most important trading partner.[15]

In 2021 German exports to Belarus were $1.77 billion of goods, led by cars, with Belarus exports valued at $958m with wood as the main product. Between 1995 and 2021 German exports rose at an average of 4.15% p.a. and Belarusian exports by 3.56% p.a..[16]

Trade has fallen, with the month of August 2023 recording just $140m and $21m in favour of Germany.[16]

Cultural relations

editSeveral thousand young Belarusians study in Germany.[citation needed] The International Aid Fund of the EU and Germany has opened partnerships with three Belarusian universities in the West. The often lamented isolation was already painful for Belarus during the times of the Soviet Union. Since the country's independence, the universities' hopes for cooperation grew, but hardly succeeded because of authoritarian state policies.[citation needed]

The only private university, the European Humanities University, founded in 1992, was closed in August 2004 under pressure from the state. It had offered European studies, linguistics and political science, largely financed by Western funds. The Institute for German Studies was also located there. The university was reopened in June 2005 in exile in Vilnius, Lithuania.

Until 2021, Minsk was also home to a Goethe Institute.[17]

Migration

editIn 2015, there were 21,151 Belarusians living in Germany and about 2,500 Germans in Belarus in 2012.[citation needed] Famous German Belarusians include:

Literature

edit- Bernhard Chiari: Alltag hinter der Front. Besetzung, Kollaboration und Widerstand in Weißrußland 1941–1944. Droste, Düsseldorf 1998, ISBN 3-7700-1607-6 , (= Schriften des Bundesarchivs, simultaneously dissertation at the University of Tübingen 1997 under the title: Deutsche Besatzungsherrschaft in Weißrussland 1941–1944).

- Wolfgang Curilla: Die deutsche Ordnungspolizei und der Holocaust im Baltikum und in Weißrußland 1941–1944. Schöningh, Paderborn 2006, ISBN 3-506-71787-1.

- Christian Gerlach: Kalkulierte Morde. Die deutsche Wirtschafts- und Vernichtungspolitik in Weißrussland 1941 bis 1944. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-930908-54-9 .

- Dimitri Romanowski: Belarus und Weimar-Deutschland: wirtschaftliche, wissenschaftlich-technische und kulturelle Beziehungen. diserta-Verlag 2015, ISBN 978-3-95935-040-2

References

edit- ^ Rainer Lindner: Historiker und Herrschaft: Nationsbildung und Geschichtspolitik in Weißrußland im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1999. p 393

- ^ John Loftus: America’s Nazi Secret. TrineDay LCC 2010, ISBN 978-1-936296-04-0 , p. 98

- ^ Eugeniusz Mironowicz: Białoruś. Trio, Warschau 1999, ISBN 83-85660-82-8, p. 136.

- ^ Alexander Brakel: Unter Rotem Stern und Hakenkreuz. Baranowicze 1939 bis 1944. Das westliche Weißrussland unter sowjetischer und deutscher Besatzung. (= Zeitalter der Weltkriege. Band 5). Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn u. a. 2009, ISBN 978-3-506-76784-4, p. 31.

- ^ Wojciech Roszkowski, Jan Kofman (Hrsg.): Biographical Dictionary of Central and Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Routledge, Abingdon u. a. 2015, ISBN 978-0-7656-1027-0 , p. 39f.

- ^ "Belarussische Emigration in Deutschland (1945-1950)" (PDF). 2015-12-30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-30. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "Сэсія Рады БНР у Остэргофэне – 29.12.1947 – Рада Беларускай Народнай Рэспублікі" (in Belarusian). 5 November 2016. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "OWEP 1/2021". OST-WEST Europäische Perspektiven (in German). Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "EU erkennt Wahl Lukaschenkos nicht an: Nur keine Einmischung in Belarus". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). ISSN 1865-2263. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "El Pais - Lukashenko is like Maduro. We do not recognize him but we must deal with him | EEAS Website". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ Amt, Auswärtiges. "Deutschland und Belarus: bilaterale Beziehungen". Auswärtiges Amt (in German). Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "German Sentenced To Death In Belarus For 'Mercenary Activity'". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2024-07-30.

- ^ "Belarus president pardons German on death row, state news agency reports". Reuters. Retrieved 2024-07-30.

- ^ ""Deutsche Wirtschaft noch zögerlich"". n-tv.de (in German). Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "Belarus Top Trading Partners 2021". www.worldstopexports.com. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ a b "Germany/Belarus". January 2022.

- ^ "Aktuell: Einstellung der Tätigkeit". Goethe-Institut (in German).