The Battle of Misiche (Greek: Μισιχή), Mesiche, or Massice (Middle Persian: 𐭬𐭱𐭩𐭪 mšyk; Parthian: 𐭌𐭔𐭉𐭊 mšyk) (dated between January 13 and March 14, 244 AD.[4]) was fought between the Sasanians and the Romans in Misiche, Mesopotamia.[5]

| Battle of Misiche | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman–Persian Wars | |||||||

Peroz-Shapur (Misiche) on the border of Asorestan (Mesopotamia) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Sasanian Empire |

Roman Empire Goths Germans | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Shapur I |

Gordian III † Philip the Arab Gaius Julius Priscus | ||||||

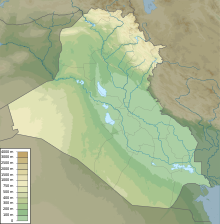

Location within Iraq | |||||||

Background

editThe initial war began when the Roman Emperor Gordian III invaded the Sasanian Empire in 243 AD. His troops advanced as far as Misiche. The location of that city (or maybe a district) is conjectural,[6] but is placed at modern Anbar.[7]

Battle

editThe Romans were defeated and it is unclear whether Gordian died during battle or was assassinated later by his own officers.

Inscription at Naqsh-e Rustam

editThe Battle is mentioned on the trilingual inscription king Shapur I made at Naqsh-e Rustam:

When at first we had become established in the empire, Gordian Caesar assembled from all of the Roman, Goth and German lands a military force and marched on Asorestan (Mesopotamia) against the Ērānšahr (Sasanian Empire) and against us. On the border of Asorestan at Misiche, a great frontal battle occurred. Gordian Caesar was killed and the Roman force was destroyed. And the Romans made Philip Caesar. Then Philip Caesar came to us for terms, and to ransom their lives, gave us 500,000 denars, and became tributary to us. And for this reason we have renamed Misiche Peroz-Shapur [literally "Victorious Shapur"].[8]

The Roman sources never admitted the defeat.[9] The contemporary and later Roman sources claim that the Roman expedition was entirely or partially successful, but the emperor was murdered after a plot by Philip the Arab.[10] However, some recent sources speculate that the Sasanian victory must not be invented and reject Philip's plot as the ultimate reason of Gordian's death. While some sources claim that it isn't likely that Gordian died during the battle, as Shapur's inscription claims,[4][11] others state he died on the battlefield.[12][13] Some sources mention a cenotaph of the murdered emperor at Zaita, near Circesium of Osroene (some 400 km north of Misiche).[14][15] The confusion of the sources about the expedition and the death of the emperor makes it possible that, after the defeat, Roman army was frustrated enough to get rid of the teenage emperor.[4] The third tradition, reported in 6th century by John Malalas and three more eastern historians in 9th to 12th century, specifies that Gordianus crushed his thigh falling off his horse in battle and died of his injury, Malalas further specifying that he died on the way back

Aftermath

editGordian's successor, Philip the Arab, was proclaimed emperor of Rome and made peace with Shapur. The next major clash between the two empires took place in 252, when Shapur defeated a large Roman force at the Battle of Barbalissos and successfully invaded Syria and part of Anatolia.

Notes

edit- ^ Brosius, Maria (18 April 2006). The Persians. ISBN 9781134359844. "Shapur I had to expect a military reaction from the Romans. For them, the loss of these cities warranted a counteroffensive and the emperor Gordian III commanded an army against Shapur I, regaining both Nisibis and Carrhae. But he suffered a major defeat in a battle at Misiche, north of Ctesiphon, in 243."

- ^ Aurelius Victor, Liber de Caesaribus, 27."7-8".; Sibylline Oracles, XIII, "13-20".

* Frye (1968), 125; Southern (2001), 235 - ^ "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ^ a b c David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay AD180-395, p.234-235

- ^ Henning, W. B. (June 1953). "Βεσήχανα πόλις: ad BSOAS., XIV, 512, n. 6 | Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies | Cambridge Core". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 15 (2): 392–393. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00111176. S2CID 183942874.

- ^ Ernst Herzfeld counters Rostovtzeff's view that it was in Assyria, writing "But Sas[anian] Asuristan is Babylonia..., and Mesiche is Pliny's Masice, the point on the Euphrates in the measurements of the Bematists." Herzfeld, The Persian Empire: Studies in Geography and Ethnography of the Ancient Near East (F. Steiner, 1968), p. 219.

- ^ Frye 1983, p. 125.

- ^ Res Gestae Divi Saporis, 3-4 (translation of Shapur's inscription at Naqsh-e Rustam).

- ^ Potter, David S. (2014). The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395. Routledge. ISBN 9781134694846.

- ^ This version of the events is accepted by Christian Körner, Philippus Arabs, Ein Soldatenkaiser in der Tradition des antoninisch-severischen Prinzipats, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2002.

- ^ Michael I. Rostovtzeff, p.23

- ^ Dignas, Beate; Winter, Engelbert (13 September 2007). Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity: Neighbours and Rivals. ISBN 9780521849258., "They probably intended to get as far as the Sasanian capital Ktesiphon but at the beginning of the year 244, Shapur I scored a decisive victory against the Roman army at Misik. Gordian III died in battle"

- ^ "Encyclopaedia Iranica". "It is understandable that Roman national pride transferred the responsibility of the defeat, in which Gordian III became the first Roman emperor to lose his life on enemy battlefield, to Philip. On the other hand, the feeling of the Sasanian triumph was immortalized in several rock-reliefs of Šāpur I, and the victory at Misiḵē was mentioned by a boastful Šāpur as the single military event within this first campaign."

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 23.5.7

- ^ Zosimus, Nova Historia, book 3

References

edit- Frye, R. N. (1983). "The political history of Iran under the Sasanians". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 116–180. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Rostovtzeff, Michael I. "Res Gestae Divi Saporis and Dura." Berytus 8:1 (1943): 17–60.

- Potter, David S. The Roman Empire at Bay AD 180–395. New York: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0-415-10058-5

- Farrokh, Kaveh. Sassanian Elite Cavalry AD 224–642. Osprey, 2005. ISBN 978-1-84176-713-0