The Battle of Drakenburg (German: Schlacht bei Drakenburg) took place on 23 May 1547 to the north of Nienburg, between the Protestant army of the Schmalkaldic League and the imperial troops of Eric II, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Prince of Calenberg. It resulted in an imperial defeat. Eric was forced to swim over the Weser River to save his own life. As a consequence, the imperialists left northern Germany, contributing to freedom of religion for Lutherans and Catholics in northern Germany.

| Battle of Drakenburg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Schmalkaldic War | |||||||

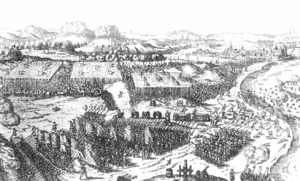

1607 etching of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Protestant Schmalkaldic troops | Catholic Imperial army, with forces of Hungary[1] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,500 infantry, 1,400 cavalry, 24 cannons | 6,000 infantry, unknown number of cavalry (including Hungarian troops), 17 cannons | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 200 dead, 400 wounded | 2,500 dead, 2,500 captured | ||||||

Context

editThe Smalkaldic League had already been defeated in the Schmalkaldic War by losing the Battle of Mühlberg on 24 April 1547. The signing of the Wittenberg Capitulation on 19 May virtually dissolved the league. Nonetheless, the northern German members of the Smalkaldic League still resisted the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

Siege of Bremen

editIn January 1547, the imperial colonel and mercenary leader Christoph von Wrisberg recruited men in Münsterland. Via the Prince-Bishoprics of Osnabrück and of Minden, which were still loyal to the emperor, Wrisberg's army marched to Bremen to begin besieging the city. In April the 19-year-old Duke Eric II joined the besieging army, which numbered 12,000 men with Eric's reinforcements. In May, Eric was informed that a Protestant army was pillaging and plundering his Principality of Calenberg and that this army was on its way to Bremen to liberate the city. Because the unsuccessful siege had taken months, using up the supplies, killing a quarter of his Landsknechte, and creating the danger of a mutiny, Eric decided to abandon the siege.

Deployment

editImperial troops

editThe imperial troops left from Bremen on 22 May, marching rapidly to attack the Protestant army. The units of the two military leaders Eric and Christoph von Wrisberg travelled along the Weser separately, one on each bank; they wanted to reunite at a river crossing. Wrisberg's troops lagged behind, however, because the sand paths caused problems. The young and ambitious duke did not wait for the latecomers and had his mercenaries march more quickly. After Eric was informed of the approach of the enemy near Drakenburg, he ordered his soldiers to get into battle formation. He had about 6,000 Landsknechte, an unknown number of horsemen, and seventeen cannons at his disposal. He positioned them east of Drakenburg towards Heemsen on an open field. He chose a corrugated terrain with sand dunes of up to 15 metres (49 ft) in height. He regarded this as an ideal secure position to meet the enemy from. His cannons would have an open field of fire as a result of their more elevated position. Additionally, his troops had the advantage of having both the sun and the wind behind them. His troops did not, however, have any avenue for evasion or retreat, since the battlefield was bordered by swamps, wetlands, and the Weser River.

Protestants

editElector John Frederick I of Saxony had led the Protestant army shortly before his capture in the Battle of Mühlberg. Originally, the army had only consisted of several Fähnlein of Landsknechte led by Albrecht VII, Count of Mansfeld. It had marched from Saxony via Nordhausen, Northeim, and Brunswick to aid the besieged city of Bremen. Troops from Brunswick, Hildesheim, Hamburg, and Magdeburg had joined the army. Thus, the army consisted of a total of 26 Fähnlein, or approximately 6,500 men, giving them a slight numeric advantage.

Battle

editThe Protestant troops came from the east and reached Eric's troops, who were entrenched on the dunes. The Schmalkaldic attackers availed themselves of a tactic attributed to Brun von Bothmer, a captain from Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. He knew the area well as he lived there as a child and proposed a pincer movement with a second offensive at the Catholics' rear. Bothmer led about one thousand mounted arquebusiers to attack from the north covertly. Both parties began the battle with simultaneous shelling and assaults. In doing so, Eric's battle formation faltered. Additionally, the Protestant cavalry divided the imperial forces by riding in between the hills. In the chaos, Eric's cavalry fled, inflicting losses upon their own infantry. The Catholic forces' escape route had been cut off by the Schmalkaldic forces as well as the nearby swampland. The only escape was the Weser River, which was flooded with spring runoff. Approximately 1,000 imperial mercenaries drowned while looking for a ford. Duke Eric II swam across the river with great difficulty, but survived.

Rearguard action

editThe units under the command of Wrisberg reached the battlefield on 23 May, but the battle was already over. Because of their numeric inferiority they retreated towards Verden. About ten kilometers north of the battlefield, the soldiers encountered the Tross of the Protestants near Hassel. It was only protected by a few soldiers, equivalent to about one Fähnlein. The imperial forces overpowered the weak Schmalkaldic forces, seizing their war chest of about 100,000 gold guilder, which eventually they gave to Emperor Charles V.

Consequences

editAs a result of the Battle of Drakenberg, the Imperial army of Eric II virtually ceased to exist; Wrisberg's troops escaped to the Netherlands and disbanded. The Protestant victory contributed to the stability and freedom of religion for Lutherans and Catholics in northern Germany. The two surviving leaders, Christoph von Wrisberg and Eric II, despised each other for the rest of their lives, accusing each other of being responsible for the defeat.

References

edit- ^ History of Hungary 1526-1686, Akadémia Publisher, Budapest 1985. ISBN 963-05-0929-6

- Drakenburg: Heimatverein (ed.): Geschichte des Fleckens Drakenburg. 1997. ISBN 3-9802780-8-5

- Freiherr Karl von Bothmer: Die Schlacht vor der Drakenburg am 23. Mai 1547, ein historisch militärische Studie, 1938, Hildesheim

- Vor über 450 Jahren am 23. Mai 1547: Die Schlacht bei Drakenburg

- Pál Zsigmond Pach, Ágnes Várkonyi R., ed. (1985). History of Hungary 1526-1686. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-0929-6.

52°41′36″N 9°13′53″E / 52.69333°N 9.23139°E