The Battle of Belmont was fought on November 7, 1861, in Mississippi County, Missouri. It was the first combat test in the American Civil War for Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, the future Union Army general in chief and eventual U.S. president, who was fighting Major General Leonidas Polk. Grant's troops in this battle were the "nucleus" of what would become the Union Army of the Tennessee.[5]

| Battle of Belmont | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War | |||||||

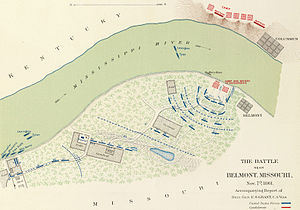

Charleston defenses, Belmont battlefield by Julius Bien & Co., Lith., N.Y. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ulysses S. Grant | Leonidas Polk | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,114 | 5,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

607 (120 killed; 383 wounded; 104 captured/missing) |

641 (105 killed; 419 wounded; 117 captured/missing) | ||||||

On November 6, Grant moved by riverboat from Cairo, Illinois, to attack the Confederacy's small outpost near Belmont, Missouri across the Mississippi River from the Confederate stronghold at Columbus, Kentucky. He landed his men on the Missouri side and marched to Belmont. Grant's troops overran the surprised Confederate camp and destroyed it. However, the scattered Confederate forces quickly reorganized and were reinforced from Columbus. They counterattacked, supported by heavy artillery fire from across the river. Grant retreated to his riverboats and took his men to Paducah, Kentucky. The battle was relatively unimportant, but with little happening elsewhere at the time, it received considerable attention in the press.[6]

Background

editAt the beginning of the war, the critical border state of Kentucky, with a pro-Confederate governor but a largely pro-Union legislature, declared neutrality between the opposing sides. Pro-Confederate Kentuckians crossed into Tennessee to enlist, but the Union men openly formed a recruiting camp inside Kentucky, violating the state's neutrality.[citation needed]

In response, Confederate Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk moved Confederate forces into Kentucky on September 3, 1861, and occupied Columbus, a key position on the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River. Three days later Union Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant seized Paducah. Grant, commanding the District of Southeast Missouri, requested permission from theater commander Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont to attack Columbus, but no orders came. For the next two months only limited demonstrations were conducted against the Confederates.[7]

Frémont learned the Confederates planned to reinforce their forces in Arkansas, and on November 1 he ordered Grant to make a feint toward Columbus to keep the Confederates there. Grant sent about 3,000 men under Col. Richard Oglesby into southeastern Missouri. Grant learned that Confederate reinforcements were moving into Missouri to intercept Oglesby's column. He sent reinforcements and also ordered Brig. Gen. Charles F. Smith to move from Paducah into southwestern Kentucky to distract the Confederates. Grant chose to attack Belmont, a ferry landing and tiny hamlet of three shacks, directly across the river from Columbus. Grant's Expeditionary Command numbered 3,114 officers and men, and was organized into two brigades under Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand and Col. Henry Dougherty, two cavalry companies, and an artillery battery. On November 6, escorted by the gunboats USS Tyler and USS Lexington, Grant's men left Cairo, Illinois on the steamboats Aleck Scott, Chancellor, Keystone State, Belle Memphis, James Montgomery, and Rob Roy.[8]

Confederate Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk had about 5,000 troops guarding Columbus. When he learned of Grant's movements, he assumed that Columbus was their primary objective and that Belmont was a feint. He ordered 2,700 men under Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow to Belmont, retaining the rest to defend Columbus.[citation needed]

When he reached Belmont, Grant found Camp Johnston, a small Confederate observation post, supported by an artillery battery. He decided to attack to keep the Confederates from reinforcing Maj. Gen. Sterling Price or Brig. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson of the Missouri State Guard, and to protect Oglesby's exposed left flank.[9]

Opposing forces

editUnion

editConfederate

editBattle

editAt 8:30 a.m. on November 7, Grant's force disembarked at Hunter's Farm, 3 mi (4.8 km) north of Belmont, out of range of the six Confederate batteries at Columbus. (The Columbus heavy water batteries featured 10-inch Columbiads and 11-inch howitzers and one gun, the "Lady Polk", was the largest in the Confederacy, a 128-pounder Whitworth rifle.) He marched his men south and east on the single road. A mile away from Belmont, they formed a battle line in a corn field. The line consisted of the 22nd Illinois Infantry, 7th Iowa Infantry, 31st Illinois Infantry, 30th Illinois Infantry, and 27th Illinois Infantry, intermixed with a company of cavalry. The Confederate battle line, on a low ridge northwest of Belmont, from north to south, was made up of the 12th Tennessee Infantry, 13th Arkansas Infantry, 22nd Tennessee Infantry, 21st Tennessee Infantry, and 13th Tennessee Infantry.[10]

Grant's attack drove in the Confederate skirmish line and for the remainder of the morning, both armies, consisting of green recruits, advanced and fell back repeatedly. By 2 p.m., the fighting became one-sided as Pillow's ill-sited line began to collapse, and the Confederates began withdrawing toward Camp Johnston. Grant was constantly at the front, leading his men. His horse was shot from under him, but his aide Captain William S. Hillyer offered his mount and Grant continued to lead. The orderly retreat began to panic when four Federal field pieces opened up on the retreating soldiers. A volley from the 31st Illinois killed dozens of Confederates, and the Union soldiers attacked from three sides and surged into the camp, after clearing the obstructions of fallen timber that formed an abatis. The Confederates abandoned their colors and their artillery, and ran toward the river, attempting to escape.[11][12]

Grant's inexperienced soldiers became, in his own words, "demoralized from their victory." Brig. Gen. McClernand walked to the center of the camp, which now flew the Stars and Stripes, and asked for three cheers. A bizarre, carnival-like atmosphere prevailed; the troops were carried away by the joy of their victory, having captured several hundred prisoners and the camp. To regain control of the men, who were plundering and partying, Grant and others ordered the camp set on fire. In the confusion and blinding smoke, wounded Confederate soldiers in some of the tents were accidentally burned to death, causing returning Confederates to believe the prisoners had been deliberately murdered.[13]

The Union troops began to march back to their transports, taking with them two captured guns and 106 prisoners. They were suddenly attacked by Confederate reinforcements brought over from Columbus on the transports Prince and Charm, who threatened to cut off Grant's retreat. These were the men of the 15th Tennessee Infantry, the 11th Louisiana Infantry, and mixed infantry under Pillow and Col. Benjamin F. Cheatham. By this time Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk had also crossed the Mississippi River from Columbus and took charge of Confederate forces during the fighting.[14] As the Union men turned to face the Confederate reinforcements, the cannon "Lady Polk" fired into their ranks from Columbus and numerous other Confederate guns opened fire. The Union gunboats exchanged fire in a battle with the Confederate batteries. Grant said, "Well, we must cut our way out as we cut our way in."[15]

Although a breach was made through the encircling Confederates, the rear of the Union column suffered severely as it ran the gantlet. When Grant reached the landing, he learned that one Union regiment was unaccounted for. He galloped back to look for it, but found only Confederate soldiers moving in his direction. He spun his horse and raced for the river, but saw that the riverboat captains had already ordered the mooring lines cast off. Grant wrote in his memoirs,

The captain of the boat that had just pushed out recognized me and ordered the engineer not to start the engine: he then had a plank run out for me. My horse seemed to take in the situation. He put his fore feet over the bank without hesitation or urging, and, with his hind feet well under him, slid down the bank and trotted on board.[16]

While embarking on the transports, the Confederates began reaching the riverside and began peppering the men and boats. The two Union woodenclads kept the attackers at bay, while the transport cut their hawsers and backed out into the current. While the riverboats were returning to Paducah, the missing Illinois regiment was seen marching upriver and the men were taken aboard.[17] In the retreat, Grant lost his bay horse, saddle, mess chest, and gold pen, while McClernand lost his "handsome iron-framed cot," field desk with dispatches, and an inkstand inscribed with his name.[18]

Aftermath

editThe Confederates viewed Belmont as a Southern victory, since Grant had staged an attack and been driven off. Polk's superior, General Albert Sidney Johnston, remarked that "The 7th of November will fill a bright gap in our military annals, and be remembered with gratitude by the sons and daughters of the South." On the evening of November 7 and the morning of November 8, Grant recalled the units he had ordered forward in Missouri and Kentucky. One Union soldier commented, "Well, Grant got whipped at Belmont, and that scared him so that he countermanded all our orders and took all the troops back to their old stations by forced marches."[19] However, Grant viewed the battle very differently. In his memoirs he states, "The two objects which the battle of Belmont was fought were fully accomplished. The enemy gave up all idea of detaching troops from Columbus. His losses were very heavy for that period of the war."[20] A Mississippi diarist viewed it as a rout of Grant and wrote "I went over to the battlefield today. It was an awful sight. The yankees under a flag of truce were burying their dead comrades. They would sometimes put as many as ten poor fellows in one grave and just barely cover them up."[21]

Union losses were 607 (120 dead, 383 wounded, and 104 captured or missing). Confederate casualties were slightly higher at 641 (105 killed, 419 wounded, 106 captured, and 11 missing). A noteworthy result of the battle was the combat and large unit command experience Grant gained. It also gave President Abraham Lincoln, who was desperate for his armies to attack the Confederates somewhere, a positive impression of Grant.[22]

Belmont Avenue in Chicago, Illinois, was named after this battle.[23]

The formerly fortified site on the Kentucky side has been designated as the Columbus-Belmont State Park, commemorating the military operations performed in the surrounding area.

As of mid-2023, the American Battlefield Trust and its partners have preserved 1.2 acres of the battlefield.[24]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "Belmont". American Battlefield Trust.

- ^ Roberts II, Donald J. "Battle of Belmont: Ulysses S. Grant's First Battle". Warfare History Network.

- ^ "Battle of Belmont". National Park Service.

- ^ "The Battle of Belmont A State Divided". The Historical Marker Database, Belmont Battle Marker; Belmont Missouri.

- ^ John Aaron Rawlins, 1866 Address, Report of the Proceedings of the Society of the Army of the Tennessee (Cincinnati: F.W. Freeman, 1877), pp. 24, 28.

- ^ Grant, Ulysses. The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant (The Complete Annotated ed.). Ulysses S. Grant Association. p. 197.

- ^ Nevin, p. 46.

- ^ Gott, p. 41; Eicher, pp. 142–43; Nevin, p. 48; Feis, p. 207.

- ^ Eicher, p. 143.

- ^ Eicher, p. 143; Hughes, pp. 36, 70, 140.

- ^ Nevin, p. 48; Eicher, p. 144.

- ^ Ronald C. White (2017). American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. Random House. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8129-8125-4.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 144–45.

- ^ Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs, The Battle of Belmont: Grant Strikes South (Univ of North Carolina Press, 1991), p. 184.

- ^ Eicher, p. 145; Nevin, p. 48.

- ^ Gott, p. 43; Nevin, p. 48.

- ^ McGhee, James E. "The Neophyte General: U.S. Grant and the Belmont Campaign" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Civil War in St. Louis

- ^ Hughes, p. 185

- ^ Hughes, pp. 190–191, 193

- ^ Ulysses Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (New York: The Library of America, 1990), 185.

- ^ Stokes, Rebecca Martin (1929). History of Grenada (1830–1880) (Master's thesis). Oxford, Miss.: University of Mississippi. 1972. p. 139.

- ^ Eicher, p. 147.

- ^ Maggio, Alice, Punkin' Donuts and the Battle of Belmont, Gapers Block website, Chicago.

- ^ "Belmont Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

References

edit- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Feis, William B. "Battle of Belmont." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Gott, Kendall D. Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry—Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8117-0049-6.

- Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs Jr. The Battle of Belmont: Grant Strikes South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8078-1968-9.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Nevin, David, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Road to Shiloh: Early Battles in the West. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1983. ISBN 0-8094-4716-9.

- National Park Service battle description

Further reading

edit- Catton, Bruce. Grant Moves South. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1960. ISBN 0-316-13207-1.

- Farina, William. Ulysses S. Grant, 1861–1864: His Rise from Obscurity to Military Greatness. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7864-2977-6.

- Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. 2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- Smith, Jean Edward. Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

External links

edit- Battle of Belmont reports from The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies at CivilWarChest.com.