The Battle of Beirut was a naval battle off the coast of Beirut during the Italo-Turkish War. Italian fears that the Ottoman naval forces at Beirut could be used to threaten the approach to the Suez Canal led the Italian military to order the destruction of the Ottoman naval presence in the area. On 24 February 1912 two Italian armoured cruisers attacked and sank an Ottoman casemate corvette and six lighters, retired, then returned and sank an Ottoman torpedo boat.

| Battle of Beirut | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italo-Turkish War | |||||||

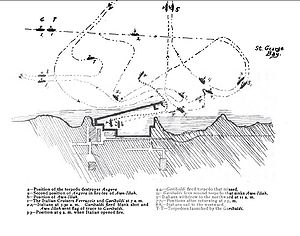

A sketch of warship positions during the Battle of Beirut. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2 armoured cruisers |

1 corvette 1 torpedo boat | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

1 corvette sunk 1 torpedo boat sunk 6 lighters sunk 49–55 killed (including 2–3 officers) 108 wounded (including 8 officers) | ||||||

| Civilian Casualties: 66 killed | |||||||

As a result of the battle all Ottoman naval forces in the region were annihilated, thus ensuring the approaches to the Suez Canal were open to the Italians. Besides the naval losses, the city of Beirut itself suffered significant damage from the Italian warships.

Background

editDuring the Italo-Turkish War, the Italian military feared that Ottoman naval forces in the Mediterranean would stage a raid on the Italian supply and troopships headed for Italian East Africa. In order to prevent such a raid, Rear Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel was ordered to clear the harbour of Beirut of what Ottoman naval vessels he might find there. Revel's force consisted of two armoured cruisers: Giuseppe Garibaldi and Francesco Ferruccio.[1] Both cruisers were of the Giuseppe Garibaldi class and armed with two 10-inch guns in turrets, ten 6-inch guns, six 4.7-inch guns, ten 6-pounders, ten 1-pounders, 2 Maxim machine guns, and five torpedo tubes.[2]

In contrast the Ottoman forces consisted of the casemate corvette Avnillah and the torpedo boat Angora.[3] Angora was a relatively new vessel completed in 1906 and armed with two 37 mm cannon as well as two 14-inch torpedo tubes with a pair of torpedoes per tube.[4] In contrast Avnillah was an antiquated ironclad corvette built in 1869. After reconstruction was completed in 1907 she was armed with four 3-inch guns and eight 6-pounders. In addition to her cannon, she was also armed with a single 14-inch torpedo tube.[5] Thus the Ottoman force was entirely outgunned by the Italians, giving them a severe disadvantage in the looming battle.

Battle

editThe two Italian cruisers approached the harbour and fired a blank shot at the Ottoman vessels lying there.[1] Upon sighting the Italian ships, the Ottoman commander on Avnillah sent out a launch under a flag of truce to communicate with the enemy. While negotiating, the Ottoman commander ordered Angora to position itself near the harbour's mole. At 07:30, Admiral Revel ordered the Ottoman launch to return with an ultimatum addressed to the Wāli of Beirut informing him to surrender his two warships by 09:00.[6] The message was received by the Wali at 08:30. The Wali was in the process of issuing an order of surrender but this was not received by the Italians by the deadline. Accordingly, at 09:00, the Italians began their attack on the Ottoman ships in the harbor.[7]

At a distance of 6,000 metres (6,600 yards), the Italians opened fire upon the Ottoman corvette. The Ottomans returned fire ineffectively until 09:35 when the Italian gunfire set Avnillah afire. Receiving heavy damage and outgunned, the corvette struck her colours and the crew abandoned ship. At this point Garibaldi sailed in close and engaged Angora at 600 metres (660 yards) with gunfire but failed to damage it.[1] Garibaldi then attempted to finish off Avnillah by firing a torpedo at her. However, the torpedo deviated from its trajectory and hit several lighters moored nearby, sinking six of them.[8] Undeterred, the Italian cruiser fired a second torpedo that struck the Ottoman corvette amidships. By 11:00 the corvette was sunk in shallow water and the pair of cruisers withdrew to the north.[9] The action was not over however; at 13:45, the Italian cruisers returned and once more engaged the Ottoman forces. The only warship left in the harbour was the torpedo boat Angora so Ferruccio moved in close and engaged it with gunfire for three minutes before it joined Avni-Illah at the bottom of Beirut's harbour. Once the fighting had ended the two Italian cruisers sailed off in a westward direction.[10]

Aftermath

editThe Ottoman naval presence at Beirut was completely annihilated, removing the only Turkish naval threat to Italian transports in the area and giving the Italians complete naval dominance of the southern Mediterranean Sea for the rest of the war. Casualties on the Ottoman side were heavy. Both Ottoman warships were sunk, with Avnillah alone taking 2 officers and 49 enlisted killed and 19 wounded.[11] In contrast, the Italian ships not only took no casualties but no direct hits from the Ottoman warships as well.[12] The damage was not restricted to the Ottoman naval vessels present at Beirut, as the city took heavy damage as well. Stray shots from the cruisers decimated the city. Fires broke out as a direct result of the stray gunfire, destroying several banks and part of the city's customs house as well as other buildings. Combined from the fires and shelling, 66 civilians were killed in the city along with hundreds of others wounded.[10]

As retribution for the Italian actions at Beirut, four days after the battle the central Ottoman government ordered the Wilyets of Beirut, Aleppo, and Damascus to expel all Italian citizens from their jurisdictions, resulting in the deportation of 50,000 Italians from the region.[10][13] Despite the retaliatory expulsion of Italian citizens from the area, the battle gave the Italian forces complete naval superiority in the approaches to the Suez Canal and Italian forces in Eritrea could now be reinforced without hesitation, eliminating much of the Ottoman threat to the region. Thus the battle was both a strategic and tactical Italian victory.[10]

Citations

edit- ^ a b c Earle (1912), p. 1092.

- ^ Brassey (1898), p. 36.

- ^ Beehler (1913), p. 54.

- ^ Gardiner (1985), p. 392.

- ^ Gardiner (1985), p. 389.

- ^ Article 5 (1912), p. 1.

- ^ Hidden (1912), p. 456.

- ^ Beehler (1913), p. 97.

- ^ Beehler (1913), p. 55.

- ^ a b c d Earle (1912), p. 1094.

- ^ Büyüktuğrul (1974), p. 84.

- ^ Beehler (1913), p. 106.

- ^ McCollum, Jonathan Claymore (2018). "The Anti-Colonial Empire: Ottoman Mobilization and Resistance in the Italo-Turkish War, 1911-1912" (PDF). UCLA History: 53. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

References

edit- "Article 5 – No Title" (PDF). The New York Times. 26 February 1912.

- Beehler, William (1913). The history of the Italian-Turkish War, September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: The Advertiser Republican. p. 58. OCLC 63576798.

awn illah.

- Brassey, T. A. (1898). Naval Annual 1898. Portsmouth: J. Griffin and Co.

- Büyüktuğrul, Afif (1974). Osmanlı Deniz Harp Tarihi (PDF) (in Turkish). Vol. 4. Genelkurmay Başkanlığı Deniz Kuvvetleri Komutanlığı. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Earle, Ralph (1912). Naval Institute proceedings, Volume 38. United States Naval Institute.

- Gardiner, Robert (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Hidden, Andrew W. (1912). The Ottoman Dynasty. New York: Nicholas Hidden.

Further reading

edit- Ellis, Raff (2007). Kisses From a Distance. Seattle: Cune Press. ISBN 978-1-885942-45-6.[permanent dead link]