This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2013) |

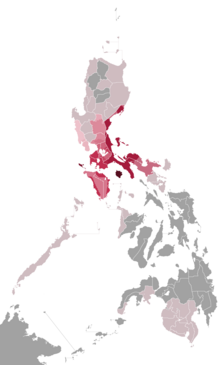

Batangas Tagalog (also known as Batangan or Batangueño [batɐŋˈgɛn.ɲo]) is a dialect of the Tagalog language spoken primarily in the province of Batangas and in portions of Cavite, Quezon, Laguna and on the island of Mindoro. It is characterized by a strong accent and a vocabulary and grammar closely related to Old Tagalog.[citation needed]

| Batangas Tagalog | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Philippines |

| Region | Batangas |

| Latin (Tagalog or Filipino alphabet); Historically Baybayin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | bata1300 |

Places where Batangas Tagalog is generally spoken | |

| |

Grammar

editThe most obvious difference is the use of the passive imperfect in place of the present progressive tense. In Manila, this is done by inserting the infix -um- after the first syllable and repeating the first syllable. In the Batangan dialect, this form is created by adding the prefix na- to the word.

This conjugation is odd,[citation needed] because it would be the passive past to Manileños. The answer to Nasaan si Pedro? (Where is Pedro?) is Nakain ng isda! (He's eating a fish!).[1] To those unfamiliar with this usage, the statement might mean "He was eaten by a fish!"; however, a Batangas Tagalog user can distinguish between the two apparently-identical forms by determining the stress in the words (nákain is eating and nakáin is eaten).

Morphology

editAnother difference between Batangan and Manila Tagalog is the use of the verb ending -i instead of -an mo, especially in the imperative. This only occurs when the verb stands alone in a sentence or is the last word in the phrase. When another word follows, Batangueños would not use the -an form.

- Example 1

- Person A: Mayroon pong nakatok sa pintô (Someone is knocking at the door.)

- Person B: Abá'y!, bukse! (Then open it!)

However,

- Person A: Mayroon pong kumakatok sa pintô (Someone is knocking at the door.)

- Person B: Abá'y, buksán mo! (Then you go open it!)

This uses the absolute degree of an adjective, not heard elsewhere.[citation needed] It is the rough equivalent to -issimo or -issima in Italian, and is missing from other Tagalog dialects.[citation needed] This is done with the prefix pagka-:

- Example 1

- Pagkaganda palá ng anák ng mag-asawang aré, ah! (Pagkaganda palá ng anák ng mag-asawang iré, ah! The child of this couple is indeed beautiful!)

- Example 2

- Pagkatagal mo ga. (You took so long.)

Second-person plural

editAnother notable characteristic of the Batangan dialect is the dual-number pronouns, referring to two things (as opposed to plural, which can be two or more). Although it has not disappeared in some other areas, this form is rarely used in the Manila dialect.[citation needed]

- Example 1

- Batangan Tagalog: Ta'na! (Let's go!)

- Manila Tagalog: Tayo na! (Let's go! Literally, "Let us...")

- Example 2

- Batangan Tagalog: Buksé mo nga iyáng telebisyón nata. (Please turn our television on.)

- Manila Tagalog: Buksán mo nga ang telebisyón natin.

Intonation tends to rise, particularly in the expression of deep emotion.

Phonology

editAnother notable difference is the closed syllable connected by glottal stop, which has disappeared from the Manila dialect and standard Tagalog or Filipino, probably influenced by Spanish, where glottal stop doesn't exist. The City of Tanauan is pronounced tan-'a-wan, although it would be pronounced ta-'na-wan by other Tagalog speakers. This is also true of words such as matamis (pronounced matam-is). Because Batangan is more closely related to ancient Tagalog, the merger of the phonemes e and i and the phonemes o and u are prevalent; e and o are allophones of i and u, respectively, in Tagalog.

Prevalent in Batangan but missing from other dialects are the sounds ey and ow. Unlike their English counterparts, these diphthongs are sounded primarily on the first vowel and only rapidly on the second; this is similar to the e in the Spanish word educación and the first o in the Italian word Antonio.

Vocabulary

editLocative adjectives are iré or aré (this) and rine or dine (here). Vocabulary is also divergent. Batangueño has several translations of the word "fall", depending on how a person falls. They may have nagdagasa (slipped), nagtingkuró (lost their balance) or nagsungabâ (fallen on their face.)

To the confusion of other Tagalog speakers,[citation needed] Batangueños use the phrase Hindî pô akó nagyayabang! to mean "I am not telling a lie!"; Manileños and other native Tagalog speakers would say Hindî pô akó nagsisinungaling! To them, the former statement means "I am not bragging (or boasting)!"

A panday is a handyman in Batangas and a smith in Manila. An apáw is "mute" ("overflow" in Manila [ápaw]; "mute" is pipi). An exclamation of disbelief is anlaah!, roughly a shorter translation of walâ iyán ("that's nothing" or "false") in Manila Tagalog.

The Batangas dialect is also known for the particle eh. While it is used throughout the province, some variations exist (such as ala eh). This particle has no intrinsic meaning; its closest equivalent in English is in the conversational context of "Well,...". In other cases it can show that the preceding word is the cause of something, much as kasi would be used. The particle eh is also spoken in other native Tagalog-speaking areas and by second-language speakers w/ the same closest English translation mentioned above w/out its variants like ala eh.

Batangas dialect is known for the term laang, translated as "only" or "just", their version of lang in Manila and their own shortened version of lámang.

Batangas dialect

edit| Old Tagalog | Modern Tagalog (Filipino) | English | In a sentence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asbag | Yabang | Egoism | Ika'y 'wag aasbag asbag dine sa pamamahay ko |

| Bilot | Tuta | Puppy | |

| Huntahan | Kwentuhan | Storytelling | Ta' muna sa amen at duon tayo maghuntahan |

| Kakaunin | Susunduin | Fetch | Ako laang ay aalis muna at may kakaunin ako sa iskul |

| Bang-aw | Ulol | Stupid | |

| Buog | Tulog | Sleep | |

| Sumbi | Suntok | Punch | |

| Taluti | Daldal | Talkative | |

| Guyam | Langgam | Ant | |

| Tarangkahan | Geyt | Gate | |

| Kahanggan | Kapitbahay | Neighbor | |

| Atungal | Iyak | Cry | |

| Baak | Hati | Sever | Lumindol sa amin at kita na nabaak ng bahay |

| Dagasa | Bulusok | Stab | Nahulog sa hagdan aba'y dagasa na eh |

| Dine | Dito | Here | |

| Barino | Galit | Angry | |

| Sura | Inis | Annoying | |

| Gahaman | Takaw | Gluttony | Magtira ka naman, ang gahaman mo sa pagkaen eh |

| Susot | Yamot | Exasperated | Ayaw kona sa bahay nakakasusot mga kapatid ko |

| Harot | Landi | Flirt | Ika'y bata palang ay napakaharot na agad |

| Litar[a] | Pasyal | Stroll | |

| Gura | Sumbrero | Hat | |

| Landang | Lagnat | Fever | |

| Kapulong | Kausap | Talking | |

| Barik | Lasing | Drunk | Ta' muna sa amen at tayo'y bumarek ng saglit |

| Suray | Liko | Swerve | Lasing ata eh at susuray suray ng lakad |

| Tubal | Maduming-damit | Dirty clothing | Maglaba ka naman ng iyong tubal at inaamag na |

| Timo | Tigil | Stop | |

| Takin | Tahol | Bark | |

| Mamay | Lolo | Grandfather | Ika'y mag mano muna sa mamay bago umalis |

| Hiso | Sipilyo | Toothbrush | |

| Asbar[b] | Garuti/Tali | Lace | |

| Nagpabulak | Nagpakulo | Boil | |

| Masukal | Malago | Grow | Yung lupa namin doon sa bundol ang sukal na ng mga damo |

| Imis | Linis | Clean | Ang dumi ng lamesa ika'y mag imis muna |

| Umis | Ngiti | Smile, Grin | |

| Umungkot | Umupo | Sit | |

| Pangkal | Tamad, Batugan | Lazy | Walanya, wala kapang nagagawa napakapangal mo naman |

| Maas/Ulaga/Malag | Tanga/Ulol | Fool | |

| Hawot | Tuyo | Dried fish | Itlog at hawot ang ulam namin nung umaga |

| Bangi | Ihaw | Grill | |

| Balatong | Munggo | Mung bean | Tuwing biyernes ay balatong ang ulam namen |

| Salop | Salok | Ganta | Pabile nga ho ako ng isang salop ng bigas |

| Sakol | Kumain gamit ang kamay | Eating using a hand | |

| Patikad | Pandalas | In a hurry | Madami ka pa atang pupuntan eh patikad kana maglakad |

| Sampiga | Sampal | Slap | 'Wag kang papakita talaga saaken at sampiga ang abot mo |

| Miha-miha | Malamya | Lousy | |

| Palanyag | Pasikat | Boastful | |

| Dagim | Maitim na kalangitan | Dark Clouds | Tingne ang langit ay dagim, mukhang uulan |

| Asbok | Singaw, Apaw, Usok | Sudden gust of smoke | Asbok na ang iyong sinasaing na kanin |

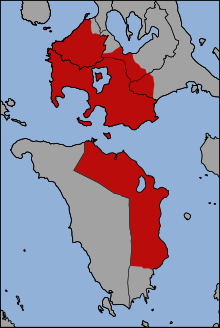

Batangas Tagalog dialect surrounding within area

edit- Outside Batangas borders

- Alaminos, Laguna

- Alfonso, Cavite

- Amadeo, Cavite

- Calamba, Laguna

- Candelaria, Quezon

- Los Baños, Laguna

- Magallanes, Cavite

- San Antonio, Quezon

- San Pablo, Laguna

- Calauan, Laguna

- Tagaytay, Cavite

- Ternate, Cavite

- Tiaong, Quezon

- Dolores, Quezon

- Cavite City, Cavite

- Bailen, Cavite

- Maragondon, Cavite

- Rest of Cavite (except Bacoor)

- Southern parts of Laguna

- Rest of Oriental Mindoro (except Bulalacao)

- Rest of Occidental Mindoro

- Scattered parts of Metro Manila, Palawan and Mindanao especially in urban areas where Batangueños and their descendants had settled, to varying degrees within these areas.

Majestic plural

editThe plural is not limited to those of lower ranks; those in authority are also expected to use this pluralisation with the first-person plural inclusive Tayo, which acts as the majestic plural. The Batangueños use the inclusive pronoun, commonly for government officials or those with authority over a territory (such as a priest or bishop).

This form is used by doctors or nurses when talking to patients. A doctor from the province will rarely ask someone how he is feeling; rather, he will ask "How are we feeling?".

Although pô and opò show respect, Batangueños replace these with hô and ohò (a typical Batangueño morphophonemic change). However, Batangueños understand the use of pô and opò (the more-common variant in other Tagalog-speaking regions).

Notes

editReferences

edit- "Regions and Dialects, Dynamic Vocabulary and Idiomatic Expressions". english-to-tagalog.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2007. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

- Pancorbo, Luis (1989). "En busca de los batangan". Los viajes del girasol (in Spanish). Madrid: Mondadori. pp. 23–35. ISBN 84-397-1489-0.