The bass trombone (German: Bassposaune, Italian: trombone basso) is the bass instrument in the trombone family of brass instruments. Modern instruments are pitched in the same B♭ as the tenor trombone but with a larger bore, bell and mouthpiece to facilitate low register playing, and usually two valves to fill in the missing range immediately above the pedal tones.

Bass trombone with two valves in F and D | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.22 (Sliding aerophone sounded by lip vibration) |

| Developed | Late 16th century |

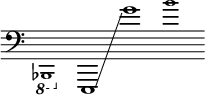

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| Musicians | |

| |

History

editThe earliest bass trombones were pitched in D, E, F or G below the tenor, which was then pitched in A.[1][2] They had a smaller bore and less flared bell than modern instruments, and a longer slide with an attached handle to allow slide positions otherwise beyond the reach of a fully outstretched arm. These bass sackbuts were sometimes called terz-posaun, quart-posaun, and quint-posaun (Old German, lit. 'third' or 'fourth' or 'fifth trombone', referring to intervals below A), though sometimes quartposaune was used generically to refer to any size of bass trombone.[3]

The earliest known surviving specimen is an instrument in G built in France in 1593.[4] Other late 16th and early 17th-century specimens of basses survive by Nuremberg makers Anton Schnitzer, Isaac Ehe, and Hans and Sebastian Heinlein.[5] These instruments match descriptions and illustrations by Praetorius from his 1614–20 Syntagma Musicum, by which time he only described basses in E or D, a fourth or a fifth below the tenor, and an octav-posaun which referred to a very large, rare, and unwieldy predecessor of the contrabass trombone.[6][7] Based on Praetorius' descriptions, Canadian trombonist and early music specialist Maximilien Brisson proposes that a quint-posaun with a extra whole-tone crook resulted in an instrument in C, capable of playing down to the lowest G1 open string of the G Violone.[8] By the late 17th century, the bass sackbut was mainly in D; German scholar and composer Daniel Speer only saw fit to mention the quint-posaun in his 1687 Grundrichtiger Unterricht treatise.[9]

Bass sackbuts were used in Europe during the Renaissance and early Baroque periods. By the 18th century, the F and E♭ bass trombones were used in Germany, Austria and Sweden, and the E♭ bass trombone in France.

The "tenor-bass" trombone

editGerman instrument maker Christian Friedrich Sattler in 1821 created an instrument he called the Tenorbaßposaune (lit. 'tenor-bass trombone'), a tenor in B♭ built with the larger bore and mouthpiece from the F bass trombone. It facilitated playing bass trombone parts in the low register, but was missing notes below E2. Treatise author Georges Kastner and other contemporary writers described a dissatisfaction with bass instruments in F or E♭, due to their slow and unwieldy slides. The invention of valves was quickly applied to create valve trombones in the 1830s which replaced the slide altogether; these became popular in military bands and Italian opera.[10]

In 1839 Sattler invented the Quartventil (lit. 'fourth valve'), a valve attachment for a B♭ tenor trombone to lower the instrument a fourth into F.[11] Intended to bridge the range gap of the tenor trombone between E2 and B♭1, it was quickly adopted for bass trombone parts, particularly in Germany. These instruments in B♭/F gradually replaced the larger bass trombones in F and E♭ over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries.[12] Late Romantic German composers specifying Tenorbaßposaune in scores intended a B♭/F trombone capable of playing below E2; Arnold Schoenberg called for four in Gurre-Lieder (1911).

The bass trombone in Britain

editFrom about the mid-nineteenth century, the bass trombone in G enjoyed a period of extended popularity in Britain and throughout most of the British Empire, and also a limited uptake in France.[13][14] In British military and brass bands, the G bass trombone became standard, built largely by makers Besson, Boosey & Co., and Hawkes & Son (and later, Boosey & Hawkes) with no valves and a slide handle for reaching the longer sixth and seventh positions. The sight of the G bass trombone in the front rank of marching bands, with the player extending the long-handled slide, led to its "kidshifter" nickname, as if clearing a path for the band through the crowds.[15]

Instruments were made as early as 1869 in France with a Quartventil valve attachment in D, which extends the low register below D♭2, the lowest (non-pedal) note in seventh position.[16] British orchestras began to employ them from the early twentieth century. In 1932, Boosey & Hawkes introduced a "Betty" model, named after Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra bass trombonist William Betty, with a D valve and a second longer tuning slide for C (to obtain the low A♭1 above the first pedal G1). While British composers, writing for a G bass trombone without a valve, avoided writing below D♭2 between 1850 and 1950, the D (or C) valve allowed British orchestral players to play European repertoire written with bass trombones in F or E♭ in mind.[14]

The G bass trombone remained in use in orchestras until the 1950s, when London orchestral players began importing larger bore American instruments in B♭ particularly by Conn.[17] The G trombone lingered on in some parts of Britain and former British colonies well into the 1980s, particularly in brass bands and period instrument orchestras.[15]

British organologist Arnold Myers suggests that the G trombone's small bore of around 12.35 millimetres (0.486 in), or 13.35 millimetres (0.526 in) for the "Betty" D valve models, lends a distinctive and uniquely British character to its sound, and historically informed performances of British works from this period should recreate this sound by employing small-bore tenor trombones and a G bass trombone.[14]

Recent developments

editThe modern bass trombone evolved largely in the United States, from the German large-bore B♭/F tenor-bass trombones in use by the late 19th century. In the early 20th century, manufacturers attempted to solve the problem of the missing low B1 on such instruments by adding a second valve. In the 1920s, manufacturers Conn and Holton made B♭/F bass trombones with a Stellventil (lit. 'static valve') that could lower the F tubing to E when manually set. The first true double-valve trombone, where the second valve can be operated while playing, was made by Los Angeles manufacturer F. E. Olds in 1937, using a second dependent valve to lower the F attachment a semitone to E.[18]

In the 1950s, some American orchestral players had double-valve instruments custom-built, and these designs were eventually adopted by manufacturers. In 1961, American maker Vincent Bach released their double-valve "50B2" model with a second dependent E valve (later E♭ and D), based on an instrument modified in 1956 for the bass trombonist with Minneapolis Symphony.[18] In the late 1960s custom instruments appeared using a second independent valve that lowered the instrument to G, and to E♭ when engaged together with the first valve.[19] The first commercially available trombone using this configuration was the Olds "S-24G" model in 1973. Although new to the bass trombone, this idea was anticipated in Germany in the 1920s by Ernst Dehmel's design for a contrabass trombone in F with two independent valves.[18]

The early 1980s saw the emergence of the axial flow valve, known as the "Thayer" valve after its American inventor, Orla Thayer. Trombonists frequently cite its more free-blowing, open-feeling playing characteristics and sound.[20] It was gradually adopted on high-end trombone models from US manufacturers by the 1990s, particularly from Edwards, S. E. Shires and Vincent Bach. This sparked further innovation in free-blowing valves; Conn patented its own CL2000 valve developed with Swedish trombonist Christian Lindberg, and the Swiss Hagmann valve was adopted by European manufacturers.[20]

Construction

editThe modern bass trombone uses the same 9-foot (2.7 m) length of tubing as the tenor trombone, but with a wider bore, a larger bell, and a larger mouthpiece which facilitate playing in the low register.[11] Typical specifications are a bore size of 0.562 inches (14.3 mm) in the slide with a bell from 9 to 10+1⁄2 inches (23 to 27 cm) in diameter.[21]

Dependent and independent valves

editThe bass trombone has typically two valves that lower the pitch of the instrument when engaged, to facilitate the register between the B♭1 pedal in first position and the E2 second partial in seventh.[22] The first valve lowers the key of the instrument a fourth to F. The second (when engaged with the first) will lower the instrument to D (or less commonly, E♭).[23]

The second valve can be configured in one of two ways, referred to as either "dependent" or "independent" (sometimes also called "in-line"). In a dependent system, the second valve is fitted to the tubing of the first valve, and can only be engaged in combination with the first.[24] In an independent system, the second valve is fitted to the main tubing next to the first valve, and can be used independently. The second independent valve typically lowers the instrument to G♭, and D when engaged in tandem with the first valve. Less commonly the second valve is tuned to G (combining to give E♭), or has a tuning slide that can tune the valve to either G or G♭ as desired.[19]

Single-valve instruments

editBefore the appearance of double valve models in the mid-20th century, bass trombones in B♭ had one valve in F. On such an instrument with a standard slide, the low B1 note immediately above the pedal range is unobtainable.[25] To solve this, bass trombones from the 19th and early 20th century were sometimes made with a valve attachment in E rather than F, or with an alternative tuning slide to lower the pitch to E♭. Today, single-valve bass trombones have a tuning slide on the valve section that is long enough to enable access to the low B1 by lowering the pitch from F to E.[26]

Range

editThe range of the modern bass trombone with two valves is fully chromatic from the lowest pedal B♭0 with both valves engaged (or even A0 with valve slides extended), up to at least B♭4. Although much of the established orchestral repertoire infrequently strays below B♭1 or above G4, and is typically written in the lower registers, there are some exceptions. French composers in the 19th century and early 20th century wrote third trombone parts for tenor trombone, writing as high as A4 (Bizet L'Arlésienne, Franck Symphony in D minor), and omitting notes below E2 except for occasional pedal notes (Berlioz in the 1830s used pedal B♭1 and A1 in Symphonie fantastique , and G♯1 in his Grande Messe des morts ).[27] English composers in the same period were writing for a bass trombone in G, and avoided writing below D♭2, even though instruments were made with a valve attachment in D by around 1900.[15]

The 20th century saw further extensions of the bass trombone range, such as the fortissimo pedal D1 in Berg's Drei Orchesterstücke (1915), and the high B4 in Kodály's 1927 Háry János suite.[27] Contemporary orchestral and solo classical pieces, as well as modern jazz arrangements, often further exploit the wide tonal range of the bass trombone.

Repertoire

editSince the Romantic period, the trombone section of an orchestra, wind ensemble, or British-style brass band usually consists of two tenor trombones and at least one bass trombone.[28] In a modern jazz big band section of typically four trombones, the lowest part is usually intended for bass trombone, often serving as the anchor of the trombone section or doubling the double bass and baritone saxophone.[29]

George Roberts (affectionately known as "Mr. Bass Trombone") was one of the first players to champion the solo possibilities of the instrument.[30] One of the first major classical solo works for the instrument was the Concerto for Bass Trombone by Thom Ritter George.[31][32]

Images

edit-

Bass trombone in F

-

Bass trombone in E♭

References

edit- ^ Herbert, Myers & Wallace 2019, p. 331–332, "Quartposaune" (Weiner, Howard).

- ^ Due to the higher church pitch used throughout parts of Renaissance Europe, tenor trombones were usually described as pitched in A, even though they are a similar size to modern B♭ tenor trombones. The first position A = 466 Hz in high pitch produces the B♭ in the modern 440 Hz pitch standard.

- ^ Baines, Anthony C.; Herbert, Trevor (2001). "Quartposaune". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.22657. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- ^ a b Pierre Colbert (1593). "Bastrombone" (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum. doi:10934/RM0001.COLLECT.329305. Object number BK-AM-61. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ignored DOI errors (link) - ^

- Anton Schnitzer (1598). "Schnitzer-Posaune (Nürnberg, 1598)" (in German). Ingolstadt: Bayerisches Armeemuseum. Accession: A 10699.

- Isaac Ehe (1612). "Bassposaune" (in German). Nuremberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum. Accession: MI168. Archived from the original on 2024-05-19. Retrieved 2024-06-22.

- Hans Heinlein (1631). "Quint-Bassposaune in Es" (in German). Musikinstrumentenmuseum der Universität Leipzig. Accession: 1914. Retrieved 26 June 2024 – via MIMO.

- ^ Praetorius 1620, p. 43–44.

- ^ Yeo 2021, pp. 18–19, "bass trombone".

- ^ Brisson, Maximilien (11 March 2024). "A new type of bass sackbut". maximilienbrisson.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ Herbert, Myers & Wallace 2019, p. 332, "Quartposaune" (Weiner, Howard).

- ^ Guion 2010, pp. 49–53.

- ^ a b Herbert 2006, p. 196.

- ^ Guion 2010.

- ^ Herbert 2006, p. 252.

- ^ a b c Myers, Arnold (2023). "The British Bass Trombone in G". Historic Brass Society Journal. 35: 16–36.

- ^ a b c Dixon, Gavin (2010). "Farewell to the Kidshifter: The Decline of the G Bass Trombone in the UK 1950–1980" (PDF). Historic Brass Society Journal. 22: 75–89. doi:10.2153/0120100011004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Antoine Courtois (1869). "Bass trombone. Nominal pitch: G + (D - D♭)". St Cecilia's Hall, University of Edinburgh. Accession: 0581. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ Yeo 2021, p. 61, "G bass trombone".

- ^ a b c Yeo, Douglas (July 2015). "Evolution: The Double-Valve Bass Trombone" (PDF). ITA Journal. 43 (3). International Trombone Association: 34–43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ a b Yeo 2021, p. 73, "independent valves".

- ^ a b Yeo 2021, p. 13, "axial flow valve".

- ^ Guion 2010, p. 64.

- ^ Herbert 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Herbert 2006, p. 182.

- ^ Yeo 2021, pp. 43–44, "dependent valves".

- ^ Herbert 2006, p. 197.

- ^ Guion 2010, p. 61.

- ^ a b Yeo 2017.

- ^ Herbert 2000, p. 174.

- ^ Tomaro, Mike; Wilson, John (2009). Instrumental Jazz Arranging: A Comprehensive and Practical Guide. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-4234-5274-4. OCLC 177016012.

- ^ Yeager, Johnathan K. (2006). Interpretive performance techniques and lyrical innovations on the bass trombone: a study of recorded performances by George Roberts, 'Mr. Bass Trombone' (DMA thesis). University of North Texas. p. 1. OCLC 1269365680. Archived from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ Moore, Donald Scott (2009). The "Concerto for Bass Trombone" by Thom Ritter George and the beginning of modern bass trombone solo performance (DMA thesis). University of Cincinnati. p. 51. OCLC 501334342. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ Rose, Keith Robert (2010). A Performance Preparation Guide to Concerto for Bass Trombone and Orchestra (1964, Revised 2001) Composed by Thom Ritter George (born 1942). Open Access Theses & Dissertations (M.Mus thesis). University of Texas at El Paso. OCLC 670436765. Archived from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

Bibliography

edit- Bevan, Clifford (2000). The Tuba Family (2nd ed.). Winchester: Piccolo Press. ISBN 1-872203-30-2. OCLC 993463927. OL 19533420M. Wikidata Q111040769.

- Praetorius, Michael (1620). Syntagma Musicum. II, De Organographia: Parts I and II. Early Music Series. Translated by David Z. Crookes. Oxford University Press (published 1986). ISBN 978-0-198-16260-5. OCLC 24613416. OL 16702850M. Wikidata Q126794034.

- Guion, David M. (2010). A History of the Trombone. Toronto: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-81087-445-9. OCLC 725775517. OL 24019524M. Wikidata Q111039945.

- Herbert, Trevor, ed. (2000). The British Brass Band: A Musical and Social History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-191-59012-2. OCLC 51682765. Wikidata Q116480763.

- Herbert, Trevor (2006). The Trombone. Yale Musical Instrument Series. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300235-75-3. OCLC 1007305405. OL 30593699M. Wikidata Q111039091.

- Herbert, Trevor; Myers, Arnold; Wallace, John, eds. (2019). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Brass Instruments. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316841273. ISBN 978-1-316-63185-0. OCLC 1038492212. OL 34730943M. Wikidata Q114571908.

- Yeo, Douglas (2017). The One Hundred Essential Works for the Symphonic Bass Trombonist. Maple City: Encore Music Publishers. ISBN 978-1-5323-3145-9. OCLC 982957903. OL 47303018M. Wikidata Q111957781.

- Yeo, Douglas (2021). An Illustrated Dictionary for the Modern Trombone, Tuba, and Euphonium Player. Dictionaries for the Modern Musician. Illustrator: Lennie Peterson. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-538-15966-8. LCCN 2021020757. OCLC 1249799159. OL 34132790M. Wikidata Q111040546.

External links

edit- Media related to Bass trombones at Wikimedia Commons

- www

.yeodoug .com - Douglas Yeo's Trombone Web Site (registered 1996) is a comprehensive resource for trombone, and bass trombone in particular