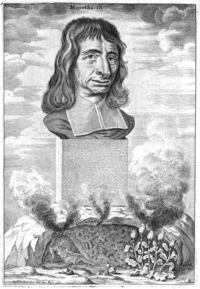

Balthasar Bekker (20 March 1634 – 11 June 1698) was a Dutch minister and author of philosophical and theological works. Opposing superstition, he was a key figure in the end of the witchcraft persecutions in early modern Europe. His best known work is De Betoverde Weereld (1691), or The World Bewitched (1695).

Life

editBekker was born in Metslawier (Dongeradeel) as the son of a German pastor from Bielefeld. He was educated at Groningen, under Jacob Alting, and at Franeker. Becoming the rector of the local Latin school, he was appointed to his satisfaction in 1657 as a pastor in Oosterlittens (Littenseradiel), and started as one of the first to preach on Sunday afternoon.

From 1679 he worked in Amsterdam, after being driven from Friesland. In 1683 he travelled to England and France. In two months time Bekker visited London, Cambridge, Oxford, Paris and Leuven, with a great interest in the art of fortification.[1]

Works

editAn enthusiastic disciple of Descartes, he wrote several works on philosophy and theology, which by their freedom of thought aroused considerable hostility.[2] In his book De Philosophia Cartesiana Bekker argued that theology and philosophy each had their separate terrain and that Nature can no more be explained through Scripture than can theological truth be deduced from Nature.[3]

His application of Cartesian metaphysics and reproach of Biblical literalism put him at odds with the Dutch Reformed Church.[4]

His best known work was De Betoverde Weereld (1691), or The World Bewitched (1695), in which he examined critically the phenomena generally ascribed to spiritual agency. He attacked the belief in sorcery and "possession" by the devil. Indeed, he questioned the devil's very existence.[2] He applied the doctrine of accommodation to account for the biblical passages traditionally cited on the issue.[5] Bekker argued that practices decried as witchcraft were little more than fatuous but harmless superstitions.[6] The book had a sensational effect and was one of the key works of the Early Enlightenment in Europe. It was almost certainly the most controversial.[7]

The publication of the book led to Bekker's deposition from the ministry. The orthodox among Dutch theologians saw his views as placing him among notorious atheists: Thomas Hobbes, Adriaan Koerbagh, Lodewijk Meyer and Baruch Spinoza. Eric Walten came to his defence, attacking his opponents in extreme terms.[8] Bekker was tried for blasphemy, maligning the public Church, and spreading atheistic ideas about Scripture. Some towns banned the book, but Amsterdam and the States of Holland never did, continuing his salary, without formally stripping him of his post.[9]

The World Bewitched is now considered interesting as an early study in comparative religion.[2][10]

Margaret Jacob coined the term "Radical Enlightment" with regards to Bekker, the brothers Johan and Pieter de la Court, and Baruch de Spinoza, that affirmed the equality of all men based on their common reason. The definition was subsequently popularized by Jonathan Israel. Jacob defined them as "pantheist, freemasons and repubblicana" characterized by a Radical criticism of religion that "anticipated Dutch 'Patriots' and Enlightment philosophers in the late eighteenth century "[11]

Later life

editIn July 1698 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London.[12] He died in Amsterdam.[2]

Selected publications

edit- De philosophia Cartesiana admonitio candida & sincera. Bekker, Balth. / Vesaliae / 1668

- The world bewitch'd; or, An examination of the common opinions concerning spirits: their nature, power, administration, and operations. As also, the effects men are able to produce by their communication. Divided into IV parts; Bekker, Balthasar / Translated from a French copy, approved of and subscribed by the author's own hand / printed for R. Baldwin in Warwick-lane / 1695

Notes

edit- ^ Bekker, Balthasar (1998) Beschrijving van de reis door de Verenigde Nederlanden, Engeland en Frankrijk in het jaar 1683. Fryske Akademy.

- ^ a b c d Chisholm 1911, p. 661.

- ^ Israel 1995, p. 895.

- ^ Fix, Andrew C (25 December 1999). Fallen angels: Balthasar Bekker, spirit belief, and confessionalism in the seventeenth century Dutch Republic. Kluwer. OCLC 41924750 – via Open WorldCat.

- ^ Wiep van Bunge et al. (editors), The Dictionary of Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Dutch Philosophers (2003), Thoemmes Press (two volumes), article Bekker, Balthasar, p. 74–7.

- ^ Barker, Charles H. (9 September 2022). "The legacies of Calvinism in the Dutch empire". Aeon. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Israel 1995, p. 925.

- ^ Wiep van Bunge et al. (editors), The Dictionary of Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Dutch Philosophers (2003), Thoemmes Press (two volumes), article Walten, Eric, p. 1065–8.

- ^ Israel 1995, p. 930.

- ^ Nooijen, Annemarie (2009) "Unserm grossen Bekker ein Denkmal?" Balthasar Bekkers 'Betoverde Weereld' in den deutschen Landen zwischen Orthodoxie und Aufklärung

- ^ M.C. Jacob, The Radical Enlightment: Pantheists, Freemasons and Republicans (London and Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1981); J.I. Israel, Radical Enlightment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernità, 1650-1750 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001). As quotes by Markus Vink (2015). Encounters on the Opposite Coast: The Dutch East India Company and the Nayaka State of Madurai in the Seventeenth Century. Brill. p. 143. ISBN 9789004272620.

- ^ "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

References

edit- Israel, Jonathan I. (1995), The Dutch Republic. Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall, 1477–1806

Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Bekker, Balthasar", Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 661

Further reading

edit- Evenhuis, R. B. (1971), Ook dat was Amsterdam, deel III. De kerk der hervorming in de tweede helft van de zeventiende eeuw: nabloei en inzinking (in Dutch), pp. 258–305

External links

edit- Ten portraits of Balthasar Bekker

- Voltaire, The Works of Voltaire, Vol. III (Philosophical Dictionary Part 1) [1764] chapter on Bekker