Bakaffa (Ge'ez: በካፋ) birth name: Missah; throne name Aṣma Giyorgis (Ge'ez: ዐፅመ ጊዮርጊስ), later Masih Sagad (Ge'ez: መሲሕ ሰገድ) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 18 May 1721 to 19 September 1730, and a member of the Solomonic dynasty. He was a son of Emperor Iyasu I and brother to Emperors Tekle Haymanot I and Dawit III.

| Bakaffa ዓፄ በካፋ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

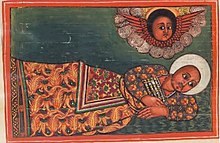

18th century depiction of Bakaffa I | |||||

| Emperor of Ethiopia | |||||

| Reign | 18 May 1721 – 19 September 1730 | ||||

| Predecessor | Dawit III | ||||

| Successor | Iyasu II | ||||

| Born | Missah | ||||

| Spouse | Mentewab | ||||

| Issue | Iyasu II Woizero Walatta Takla Haymanot Woizero Walatta Israel | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | House of Solomon | ||||

| Father | Iyasu I | ||||

| Religion | Coptic Orthodox | ||||

Sources

editJames Bruce describes Bakaffa as faced with the increasing enfeeblement of the Ethiopian Empire as well as growing intrigue and conspiracies. To respond to these challenges, writes Bruce, Bakaffa was "silent, secret, and unfathomable in his designs, surrounded by soldiers who were his own slaves, and by new men of his own creation." In writing his account of this Emperor's reign, Bruce claims that at the time of his writing no Royal Chronicle of his reign existed, because it "would have been a very dangerous book to have been kept in Bacuffa's time; and, accordingly, no person chose ever to run that risk; and the king's particular behaviour afterwards had still the further effect, that nobody would supply this deficiency after his death, a general belief prevailing in Abyssinia that he is alive to this day, and will appear again in all his terrors."[1] As a result, Bruce's account of Bakaffa's reign consists of a collection of impressionistic vignettes of selected events—his travels through Ethiopia in disguise, his feigned death, his first meetings with people who were to play an important role during his rule—which support this portrait.

In contrast, the editor of the 1805 edition of Bruce's work, Alexander Murray, excised all but the first two paragraphs of his chapter on this ruler, replacing Bruce's material with a summary of a chronicle of the reign, stating that "the annals of this period are very complete, the public transactions of Bacuffa are well known, though his motives seldom escaped from his own impenetrable breast."[2]

Life

editBakaffa spent his childhood confined on Wehni, but during the unrest in the last year of Emperor Yostos' reign he escaped to live with the Oromo; when he was recaptured, part of his nose was cut off as punishment, with the intent of disqualifying him for the throne.[2] Nevertheless, upon the death of his brother Emperor Dawit III, he was selected to succeed him against the wishes of a sizable group backing Welde Giyorgis, the son of Nagala Mammit.

While his reign was disturbed by few wars, Donald Levine observes that he "spent his days breaking the power of the feudal lords and strengthening the hand of the monarchy."[3] However, Paul B. Henze believes that "his most valuable contribution to his capital and his country was his second wife, Mentewab.[4]

He also devoted much of his rule travelling in disguise around his realm to seek out inequities to correct, acts which, according to Edward Ullendorff, "have long become part of Ethiopian folklore."[5] James Bruce retells at length the folk story of how Bakaffa met Empress Mentewab (his second wife) while he was on one of his frequent trips in disguise, and fell ill while visiting her home province of Qwara. He was put to bed in her father's house and she had nursed him during his illness, and upon his recovery, he had married her.[6]

An enduring tragic mystery is that of the death of his first wife. The Emperor had crowned his previous wife in the palace, and she had proceeded to the banqueting hall to preside over her coronation banquet. After taking part in the meal, she suddenly took ill and died that very night. Rumors of poisoning were rife. His second wife, Mentewab arrived as the new Empress in Gondar to a court that was suspicious and full of intrigue and danger. That she was able to engineer her way to power and influence in such an environment is very impressive, not to mention the dominant role that she would seize upon her husband's death.

However, Bakaffa's reign at the time was not entirely happy. Fearful of the danger of insurrections against him, in 1727 he tested the attitude of his subjects by hiding in his palace for many days, with the result that the nobles and populace were alarmed. The governor of the city put a guard around the Royal Enclosure, at which point the crafty ruler emerged and rode to the Debre Berhan Selassie Church. While the unfortunate governor and several associates were executed the next day, Richard Pankhurst notes the public shared in this disaffection, quoting James Bruce that when rumor of Bakaffa's death circulated, "the joy was so great, so universal, that nobody attempted to conceal it"; and when he revealed that he was actually still alive,

- There was no occasion to accuse the guilty. The whole court, and all strangers attending there upon business, fled, and spread a universal terror through the whole streets of Gondar. [...] What this sedition would have ended in, it is hard to know, had it not been for the immediate resolution of the king, who ordered a general pardon and amnesty to be proclaimed at the door of the palace.[7]

Notwithstanding this clemency, Bakaffa later was quoted as remarking that although he loved the inhabitants of Gondar, they only responded with hate.

Bakaffa added several new buildings to the capital city of Gondar. He is credited with the construction of a vast banqueting hall on the north side of the Royal Enclosure, which might be the structure where he held a lavish feast for all in 1725; next to it stands Mentewab's Castle, which might have been built by Bakaffa's son and heir Iyasu II, but definitely was constructed before Mentewab retired from the capital to her palace at Qusquam in 1750. These are last new buildings erected in the Royal Enclosure.[8]

A marvel of his reign, recorded in his Royal Chronicle,[9] was the construction of a new kind of boat on Lake Tana in 1726 by two foreigners from Egypt, Demetros and Giyorgis, unlike the traditional ones built from reeds.

References

edit- ^ Bruce, Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1790 edition), vol. 2 pp. 596f

- ^ a b Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1805 edition), vol. 4 p. 76

- ^ Donald N. Levine, Wax and Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopian Culture (Chicago: University Press, 1965), p. 24

- ^ Henze, Layers of Time, A History of Ethiopia (New York: Palgrave, 2000), p. 104

- ^ Edward Ullendorff, The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People, second edition (London: Oxford Press, 1965), p. 81

- ^ Bruce, Travels to Discover (1790 edition), vol. 2 pp. 597ff

- ^ Bruce, Travels to Discover (1790 edition), vol. 2 pp. 601f

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Ethiopia, the unknown land: a cultural and historical guide (London: I.B. Tauris, 2002), pp. 132-4.

- ^ Translated in part by Richard K.P. Pankhurst in The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles (Addis Ababa: Oxford University Press, 1967).