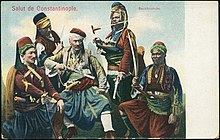

A bashi-bazouk (Ottoman Turkish: باشی بوزوق başıbozuk, IPA: [baʃɯboˈzuk], lit. 'one whose head is turned, damaged head, crazy-head', roughly "leaderless" or "disorderly") was an irregular soldier of the Ottoman army, raised in times of war. The army primarily enlisted Albanians and sometimes Circassians as bashi-bazouks,[1] but recruits came from all ethnic groups of the Ottoman Empire, including slaves from Europe or Africa.[2] Bashi-bazouks had a reputation for being undisciplined and brutal, notorious for looting and preying on civilians as a result of a lack of regulation and of the expectation that they would support themselves off the land.[1][3]

Albanian Bashi-Bazouk Chieftain by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1881. | |

| Founded | 17th century |

|---|---|

| Named after | Turkish word for crazy-head |

| Founding location | Istanbul, Ottoman Empire |

| Years active | Unknown |

| Territory | Balkans, Eastern Europe |

| Allies | |

| Rivals | |

Origin and history

editAlthough the Ottoman armies always contained irregular troops such as mercenaries as well as regular soldiers, the strain on the Ottoman feudal system, caused mainly by the Empire's wide expanse, required a heavier reliance on irregular soldiers. They were armed and maintained by the government, but did not receive pay and did not wear uniforms or distinctive badges. They were motivated to fight mostly by expectations of plunder.[4] Though the majority of troops fought on foot, some troops (called aḳıncı) rode on horseback. Because of their lack of discipline, they were not capable of undertaking major military operations, but were useful for other tasks such as reconnaissance and outpost duty. However, their uncertain temper occasionally made it necessary for the Ottoman regular troops to disarm them by force.[3]

The Ottoman army consisted of the following:

- The Sultan's household troops, called Kapıkulu, which were salaried, most notable being Janissary corps.

- Provincial soldiers, which were fiefed (Turkish Tımarlı), the most important being Timarli Sipahi (lit. "fiefed cavalry") and their retainers (called cebelu lit. armed, man-at-arms), but other kinds were also present

- Soldiers of subject, protectorate, or allied states (the most important being the Crimean Khans)

- Bashi-bazouks, who usually did not receive regular salaries and lived off loot

Many Afro-Turks, Albanians, Crimean Tatars, Muslim Roma, and Pomaks were bashi-bazouks in Rumelia.

An attempt by Koca Hüsrev Mehmed Pasha to disband his Albanian bashi-bazouks in favor of his regular forces began the rioting which led to the establishment of Muhammad Ali's Khedivate of Egypt.[5] The use of bashi-bazouks was abandoned by the end of the 19th century. However, self-organized bashi-bazouk troops still appeared later.

The term "bashibozouk" has also been used for a mounted force, existing in peacetime in various provinces of the Ottoman Empire, which performed the duties of gendarmerie.[citation needed]

Reputation and atrocities

editThe bashi-bazouks were notorious for being violently brutal and undisciplined,[6] thus giving the term its second, colloquial meaning of "undisciplined bandit" in many languages. The term was popularised in the 20th century by the comic series The Adventures of Tintin, where the word is frequently used as an insult by Captain Haddock.[7]

The Batak massacre (1876) was carried out by thousands of bashi-bazouks sent to quell a local rebellion. Likewise, bashi-bazouks perpetrated the massacres of Candia in 1898 and Phocaea in 1914. During the 1903 Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising in Ottoman Macedonia, these troops burned 119 villages and destroyed 8400 houses, and over 50,000 Bulgarian refugees had to flee into the mountains.[8]

-

Bashi-bazouks carrying out the Batak massacre. Antoni Piotrowski, (1889).

-

Bashi-bazouks' atrocities in Ottoman Bulgaria. Unknown author, (1877).

-

The Bulgarian Martyresses (1877), painting by Konstantin Makovsky depicting the rape of two Bulgarian women in a church by one African-looking and two Turkish-looking bashi-bazouks, during the April Uprising.[9]

Depictions in art

edit-

An Albanian bashi-bazouk in Egypt. Painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1870.

-

Drawing of a bashi-bazouk by Francis Davis Millet, 1889.

-

An Albanian bashi-bazouk painted by Jean-Léon Gérôme in the 1860s.

-

A bashi-bazouk contemplating his loot. Painting by Émile Vernet-Lecomte, 1862.

-

An African bashi-bazouk, painted by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1860s.

-

Two captured bashi-bazouks, painted by Vasily Vereshchagin, 1878.

See also

edit- Mercenary

- Pindari, irregular horsemen in 18th-century India

- Military of the Ottoman Empire

- Military history of Turkey

References

edit- ^ a b Houtsma 1993, p. 670.

- ^ Vizetelly 1897, p. 83.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Montgomery 1968, p. 246

- ^ Inalcık, Halil (1979). "Khosrew Pasha". The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. V, fascicules 79–80. Translated by Gibb, H. A. R. (new ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 35ff.

- ^ Fermor, Patrick Leigh (2013). The Broken Road. John Murray. p. 21. ISBN 9781590177549.

[T]he faintest stirrings would unloose a whirling of janissaries and spahis and later on, and perhaps the worst, bashi-bazouks. They adorned the towns with avenues of gibbets, the burnt villages with pyramids of heads and the roadsides with impaled corpses.

- ^ Horatio Clare (11 March 2008). Running for the Hills: A Memoir. Simon and Schuster. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-0-7432-7428-9.

- ^ Glenny, Misha (2012). The Balkans. USA: Penguin Books. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-14-242256-4.

- ^ Alexis Heraclides; Ada Dialla (2015). Humanitarian Intervention in the Long Nineteenth Century: Setting the Precedent. Oxford University Press. pp. 185–. ISBN 978-0-7190-8990-9.

Sources

edit- Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor, ed. (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-08265-6.

- Vizetelly, Edward (1897). The Remininiscences of a Bashi-bazouk. J.W. Arrowsmith.

- Ottoman warfare, 1500–1700 by Rhoads Murphey. London : UCL Press, 1999.

- Özhan Öztürk (2005). Karadeniz (Black Sea): Ansiklopedik Sözlük. 2 Cilt. Heyamola Yayıncılık. İstanbul. ISBN 975-6121-00-9.

- Montgomery, Viscount Bernard (1968). A History of Warfare, The World Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-688-01645-6.