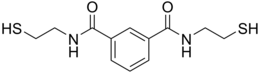

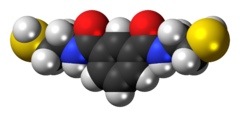

BDTH2 (also called BDET and BDETH2; trade names B9, MetX, and OSR#1) is an organosulfur compound that is used as a chelation agent.[2] It is a colourless solid. The molecule consists of two thiol groups and linked via a pair of amide groups.[3]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

N1,N3-Bis(2-sulfanylethyl)benzene-1,3-dicarboxamide | |

| Other names

BDET; BDTH2; BDETH2; N,N′-Bis(2-mercaptoethyl)-1,3-benzenedicarboxamide; N1,N3-bis(2-mercaptoethyl)isophthalamide; NBMI;

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| MeSH | 1,3-benzenediamidoethanethiol |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H16N2O2S2 | |

| Molar mass | 284.39 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.23 g/mL |

| Melting point | 132 to 135 °C (270 to 275 °F; 405 to 408 K)[1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Preparation

editThe compound was reported in about 1994 after a search for chelating agents selective for mercury. It was licensed in 2006 to CTI Science with the long-term goal of using BDTH2 to treat mercury poisoning.[4] This compound is prepared by treating isophthaloyl dichloride with two equiv of cysteamine:[1][2]

Use

editEnvironmental remediation

editBDTH2 can be used to chelate heavy metals like lead, cadmium, copper, manganese, zinc, iron, and mercury from ground water, coal tailings, gold ore, waste water of battery-recycling plants, and contaminated soil.[2]

BDTH2 appears to bind mercury more strongly than do other chelators. The mercury-BDT complex does not break down even at high pH and in the presence of cyanides, as in waste water of gold mines. The particular stability of the mercury bond can be attributed to the linear position of the two thiols.[5] The company Covalent Research Technologies had investigated BDTH2 for the removal of mercury from flue gas without success.[4]

Clinical use

editAnimal experiments with inorganic mercury showed, that BDTH2 effectively binds mercury in the body, and the resulting mercury derivative is excreted in the feces. Experimental animals showed no signs of poisoning. It is unclear, how the BDTH2-mercury-chelate behaves in the long term. BDTH2 is lipophilic, as opposed to DMPS and DMSA; this enables it to cross lipid membranes, including the blood-brain-barrier, and enter bone marrow.[4] In animal experiments, mercury in brain tissue neither increased nor decreased. There are indications that the BDTH2-mercury-compound moves into adipose tissue.[3] It is unknown how BDTH2 works with methyl-mercury.

BDTH2 appears to bind copper and zinc in vivo weakly. In contrast, DMPS und DMSA bind these ions more strongly. Its affinity is low for other "hard" ions, e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and K+.[3]

Until July 2010, CTI Science sold BDTH2 as a nutritional supplement under the name OSR#1.[6] Since OSR#1 didn't fulfill criteria of a nutritional supplement, its sale was stopped under pressure of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.[7] In January 2012, BDTH2 was designated by the European Commission as an orphan drug, which guarantees CTI Science ten years of exclusive marketing rights.[8] In April 2012, the FDA designated the compound as an orphan drug.[9]

Potential applications

editLike most thiols, BDTH2 binds to mercury salts to form thiolate complexes. In principle, it could be used to remove mercury from water for industrial applications under a wide range of conditions, including the high pH and cyanide of the effluent from gold mining. In industrial use, BDTH2 is easy to make and can be used either as-is or in the form of sodium or potassium salts that are more soluble in water.[1]

BDTH2 binds to mercury with a strong, nonpolar covalent bond within a water-insoluble organic framework. The resulting BDT–Hg precipitate is stable, and leaches mercury only under highly acidic or basic conditions. BDTH2 also binds to other elements, including arsenic, cadmium, copper, lead, and selenium.[1] It is effective and economical for removing small traces of mercury from polluted soil, as the precipitate is inert and can be left in the soil after treatment.[10]

Dietary supplement and controversy

editBDTH2 had been marketed under the name OSR#1 as a dietary supplement for treatment of autism.[11] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration determined that BDTH2 is a drug rather than a supplement and issued a warning,[12][13] resulting in its removal from the market.[14] The main proponent of the compound, Dr. Boyd Haley, was chairman of the department of chemistry where research is also conducted on the utility of this compound for remediation of heavy metal pollution.[1][11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e Blue LY, Jana P, Atwood DA (June 2010). "Aqueous mercury precipitation with the synthetic dithiolate, BDTH2". Fuel. 89 (6): 1326–1330. Bibcode:2010Fuel...89.1326B. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2009.10.031.

- ^ a b c Blue LY, Immobilization of mercury and arsenic through covalent thiolate bonding for the purpose of environmental remediation, Dissertation, University of Kentucky, 2010

- ^ a b c Clarke D, Efficacy of a Novel Chelator for Mercury Chelation and Distribution, Dissertation, Arkansas State University, December 2012

- ^ a b c Mullin, Rick (3 March 2014). "A mercury chelator". C&EN Online. 92 (9): 18–19.

- ^ Blue, Lisa Y.; Van Aelstyn, Mike A.; Matlock, Matthew; Atwood, David A. (April 2008). "Low-level mercury removal from groundwater using a synthetic chelating ligand". Water Research. 42 (8): 2025–2028. Bibcode:2008WatRe..42.2025B. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2007.12.010.

- ^ Forrest Health Online:"OSR#1 - 30 100mg caps - Forrest Natural Health Supplements". Archived from the original on 2010-12-23. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ Warning letter CIN-10-107927-14 17 June 2010 FDA to CTI Science Inc.

- ^ EU/3/11/944 (PDF; 112 kB) NBMI as orphan drug by the EC

- ^ "Enforcement Reports".

- ^ Blue LY, Van Aelstyn MA, Matlock M, Atwood DA (2008). "Low-level mercury removal from groundwater using a synthetic chelating ligand". Water Res. 42 (8–9): 2025–8. Bibcode:2008WatRe..42.2025B. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2007.12.010. PMID 18207488.

- ^ a b Tsouderos T (2010-01-17). "OSR#1: industrial chemical or autism treatment?". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2010-02-21. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ^ Tsouderos, Trine (June 23, 2010). "FDA warns maker of product used as alternative autism treatment". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ "Warning Letter CIN-10-107927-14". Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services / Food and Drug Administration. June 17, 2010. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Tsouderos, Trine (July 26, 2010). "Controversial supplement to come off shelves". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 30 July 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.