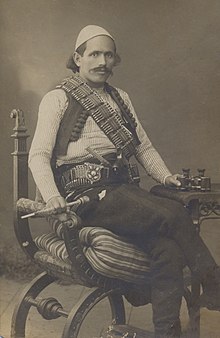

Azem Bejta (10 December 1889 – 15 July 1924), commonly known as Azem Galica, was an Albanian nationalist, resistance fighter and rebel who fought for the unification of Kosovo with Albania. He is known for leading the Kachak Movement against the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Azem Galica | |

|---|---|

Azem Galica | |

| Born | Azem Bejta 10 December 1889 |

| Died | 15 July 1924 (aged 34) Junik, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (today Kosovo) |

| Spouse | Shota Galica |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Provisional Government of Albania, Committee for the National Defence of Kosovo |

Early life

editAzem Bejta was born into a poor Albanian family in the village of Galicë in the broader Drenica region. His family descended from the Kuçi tribe (fis).[1] He was the son of Bejta Galica, a rebel who died fighting against the Ottoman Empire and Serbian forces. Azem began fighting the Kingdom of Serbia in 1912, opposing their rule in Kosovo.[2][3][4]

Early activities

editBalkan Wars

editAzem Galica and his Kaçak fighters resisted the Serbian invasion of Kosovo during the Balkan Wars and in the early parts of World War I.[2]

World War I

editIn the winter of 1915–1916, during World War I, Serbia was occupied by the Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary after the Central Powers won a victory in Kosovo in late November 1915 - Azem Galica began an armed resistance against the new invaders.[5] Azem married Shote Galica that same year, and she joined his unit of fighters. From 1915-1918, Azem opposed both the Austro-Hungarian and the Bulgarian forces which had occupied Kosovo.[2][6] The Austrians had executed his two brothers.[7]

In Autumn of 1918, Azem Galica and hundreds of his men forced the surrender of an Austrian regiment between Mitrovica and Peja; Serbian Chetnik commander Kosta Pećanac arrived soon after, and the two leaders met in the villages of Pridoricë and Varagë and discussed joint operations against the Austrians. After making empty and false promises to the Albanians on behalf of King Petar, Kosta Pećanac and his men soon left for Serbia and no agreements were made.[8][9][10][11][7] Nonetheless, on the 15th of October, 1918, Azem and his Albanians occupied Peja and captured the Austro-Hungarian barracks, which consisted of 4,000 soldiers and 70 officers. Azem was awarded two medals by a French general for his efforts.[12][7]

However, after persuasion by Luigj Gurakuqi, Prenk Bib Doda and Fejzi Alizoti, as well as the opening of 300 Albanian schools, the right to fly the Albanian flag, and assurances that the Austrians would respect the customs of the country, the Albanian language, and both the Christian and Muslim religions, Azem Galica accepted the Austrian occupation.[5]

In 1918, the Serbian Army pushed the Central Powers out of Kosovo. After the war ended, Kosovo found itself included in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians (later known as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) on 1 December, 1918. Galica once again became an outlaw, fighting against the soldiers and police of the King and he was hunted by Serbian authorities as a fugitive.[13][7]

Kachak Movement

editResistance against Yugoslavia (1919-1920)

editBy late 1918, Azem commanded a force of around 2,000 fighters.[7] On the 29th of April, 1919, there was a confrontation near Rudnik in the Peja district between Serbian troops and Azem Galica's band of fighters in which the Serbs were forced to withdraw from Peja itself, having left 29 dead soldiers behind.[12] Disaffected Kosovar Albanians who had rallied around Hasan Prishtina formed a 'Committee for the National Defence of Kosovo' in Shkoder in 1918, their main demand being the unification of Kosovo with Albania.[14] On 6 May 1919, an appeal by the Kosovo Defence Committee for a general uprising resulted in a large-scale rebellion, known as the Kachak Movement, led by Azem Galica. The best known of the Kachak leaders were Bajram Curri, Hasan Prishtina and Azem. The Committee issued strict guidelines to their Kachaks, urging them to refrain from harming or mistreating local Slavs, and to refrain from burning houses or churches.[14][15]

Azem and the other Kachak leaders presented a set of demands to Serbian officials: they asked the Kingdom of Yugoslavia to stop killing Albanians, to recognise the Kosovo Albanians' right to self-government, and to stop both the Yugoslav colonization program of Kosovo and the military actions of Yugoslav forces on the pretext of disarmament. They also requested that Albanian schools were opened, that the Albanian language was made an official administrative language, and that the families of the Albanian rebels were no longer interned by the authorities. The Yugoslavs responded to the attempts at communication with increased violence.[16]

Fighting blew up in Drenica, Azem Galica's home territory.[17] It was estimated that there were 10,000 active rebels under Azem's command at this time.[17][18] By November of 1920, Yugoslav forces succeeded in suppressing a rebellion in the Drenica region, and Azem and Shote Galica fled to Shkodra.[15]

Resurgence of the Kachak Movement (1921-1923)

editIn April 1921, Azem Galica returned to Kosovo to revive the Kachak Movement.[15] As a calculated act of provocation, the Yugoslav government had been interned the families of suspected Kachaks to camps in central Serbia during the spring of 1921, which intensified the resistance. In July 1921, the Kosova Committee submitted a document to the League of Nations in which they reported Serbian atrocities against Albanians and identified the victims. They recorded that Serbian forces killed 12,371 people in Kosovo, imprisoned 22,110 and burnt down roughly 6,000 houses.[19]

The Neutral Zone of Junik was established in November 1921 by the authority of the League of Nations following constant border disputes between Albania and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the frequent military intrusion from the Yugoslav side since 1918 into the Albanian side as well as continuous skirmishes between the Albanian guerrillas and Yugoslavian army.[20] Azem Galica's band of Kachaks used the Neutral Zone of Junik as their base, as did most of the other Kachak bands. He was housed by Tafë Hoxha, a local in Junik.[21][6]

Despite the Kachak Movement's popularity amongst Albanians, it was not only opposed by the Yugoslav government, but also by Ahmet Bej Zogu and his supporters. In 1922, Zog - who was at this time Minister of the Interior in Albania and a known opponent of the Kosova Committee, began to disarm Albanian Highlander tribes in the north of the country as well as those within the Neutral Zone of Junik.[7] Zogu also gave orders to the relevant administrative bodies of the state to attack the Neutral Zone and to liquidate the Kachaks wherever they found them, but particularly in Junik.[22]

In March of 1922, Bajram Curri, Hasan Prishtina and Elez Isufi led an unsuccessful attempt at overthrowing Zog, who eventually became the Prime Minister of Albania on 2 December 1922. His quarrels with the leaders of the Kosovar Albanians made him a fierce opponent of the Kachak Movement, and of Kosova in particular. Zog's ascension to power resulted in the end of Albanian governmental support for Kosova, and he sentenced Azem Galica to death in absentia and gradually assassinated the leaders of the Kosova Committee.[14][7] In January of 1923, Curri and Prishtina led another unsuccessful attempt at overthrowing Zog; in between these two unsuccessful attempts, Zogu entered into a secret agreement with the Yugoslavs, promising to destroy the Kachak bands among other things.[14] Azem Galica and his main force of around 1,000 Kachaks were betrayed to the Yugoslavs by Zogu's regime.[7] In 1923, Zog's forces, in coordination with the Yugoslavs, invaded the Neutral Zone of Junik; the Kachaks left the zone and moved further into Kosovo, and the area was handed to the Yugoslavs.

Death and aftermath

editAside from their control of the Neutral Zone of Junik, the Kachak Movement succeeded in creating a "free zone" in Galica (Azem's hometown) and three nearby villages, which was called "Arberia e Vogel" (little Arberia). The Yugoslav kingdom, however, had no intention of letting this zone survive, and with superior firepower and troop numbers they moved into Drenica.

Bejta was seriously wounded in action by the Royal Yugoslav Army and later died from his wounds on 15 July 1924. His last wish was for his body not to be found by the Serbs, and thus he was buried in a deep cave somewhere in Drenica.[13] The death of Galica dealt a mortal blow to the armed resistance against Yugoslav military presence in Kosovo, which Azem had led for the past eight years.[5] The Yugoslavs intensified their repression of the Albanian movement in Kosovo.[5]

After the assassination of Albanian patriot and activist Avni Rustemi on the orders of Zog, the Kosova Committee leaders once again attempted to overthrow Zog. They succeeded during the June Revolution of 1924, and the progressive nationalist government of Fan Noli was installed in Zog's place. However, with the help of the Yugoslavs, Zog managed to once again ascend to power on 24 December 1924 and proceeded to suppress the Kosova Committee and either assassinate or force its leaders into exile. These Albanian patriots were only some of the Albanian nationalist activists and figures assassinated on the orders of Zog and his regime.[7][14]

Azem's wife, Shote, took control of Azem's band of Kachak fighters upon his death and continued to fight against the Yugoslav occupation of Kosovo. She fought alongside Bajram Curri in Has and Luma against Serbian troops who had supported Zog during his return to power in December of 1924, and she continued to lead the fighting in Kosovo until 1926, when she was severely wounded and decided to move to Albania. Shote died in poverty in 1927, looking after the orphans left behind by her fellow fighters who were killed during the resistance. She received no medical or social support from Zog's regime.[13][6]

Legacy

editAs a national hero, Galica epitomized the Albanian Kosovar resistance.[23] In the long term, the killing of Galica and of many others stimulated and set an example of Albanian resistance against repression and inequality in Kosovo.[23]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Tahiri, Bedri (2010). "Rrëfime të Gjalla për Luftën e Drenicës". Albaniapress.

- ^ a b c Elsie, Robert (2004). Historical dictionary of Kosova. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780810853096.

- ^ Haxhiu, Ajet (1982). Shota dhe Azem Galica. Shtëpia Botuese "8 Nëntori". p. 6.

- ^ Di Lellio, Anna (2009). The battle of Kosovo, 1389: an Albanian epic. London: I. B. Tauris. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9781848850941.

- ^ a b c d Owen Pearson (2004). Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History: Volume I: Albania and King Zog. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781845110130. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Kofman, Jan; Roszkowski, Wojciech (2016). Biographical Dictionary of Central and Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Taylor & Francis. p. 272. ISBN 9781317475941.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Banac, Ivo (2015). The National Question in Yugoslavia. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501701931.

- ^ Prifti, Kristaq (2002). Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime: Periudha e pavarësisë : 28 nëntor 1912-7 prill 1939. Botimet Toena. p. 442. ISBN 9789994312696.

- ^ Verli, Marenglen (2007). Shqipëria dhe Kosova historia e një aspirate. Botimpex. pp. 25, 179. ISBN 9789994380145.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel (2002). Kosovo: A Short History. London, England: Pan. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-330-41224-7.

- ^ Ott, Raoul (2023). Hegemoniebildung und Elitentransformation im Kosovo: Von der spätosmanischen Herrschaft bis zur Republik. Berlin: Logos-Verlag. p. 119. ISBN 9783832557201.

- ^ a b Destani, Bejtullah D.; Elsie, Robert (2018). Kosovo, a documentary history: from the Balkan Wars to World War II. London New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781786733542.

- ^ a b c Elsie, Robert (2004). Historical Dictionary of Kosova. The Scarecrow Press. p. 63. ISBN 0-8108-5309-4.

- ^ a b c d e Paulin Kola (2003). The Search for Greater Albania. ISBN 9781850655961. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Elsie, Robert (2011). Historical dictionary of Kosovo (2. ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. xxxvi. ISBN 9780810874831.

- ^ Ott, Raoul (2023). Hegemoniebildung und Elitentransformation im Kosovo: Von der spätosmanischen Herrschaft bis zur Republik. Berlin: Logos-Verlag. p. 121. ISBN 9783832557201.

- ^ a b Tim Judah (2002). Kosovo: War and Revenge; Second Edition. ISBN 0300097255. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ Pettifer, James (2020). War in the Balkans: conflict and diplomacy before World War I (Paperback ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 32. ISBN 9780857726414.

- ^ Clark, Howard (2000). Civil resistance in Kosovo. London Sterling, Va: Pluto Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780745315690.

- ^ Kristaq Prifti (Instituti i Historisë - Akademia e Shkencave e RSH) (1993). The truth on Kosova. Encyclopaedia Publishing House. p. 163. OCLC 30135036.

The intervention of the League of Nations brought about the formation of a "neutral zone" of Junik in November 1921. Within the creating of the "neutral zone" of Junik, the military reduced the intensity of its actions...

- ^ Bedri Tahiri (2 August 2008), Hasan Prishtina, truri i levizjes kombetare shqiptare (1908- 1933) (in Albanian), Prishtina: Pashtriku.de, retrieved 18 February 2014,

Si shumica e çetave kaçake, edhe Çeta e Azemit kaloi atje. Me veti i kishte edhe dy gratë: Shotën e Zojën dhe u vendos në shtëpinë e Tafë Hoxhës. Nuk kaloi shumë kohë e në Zonën Neutrale të Junikut erdhi edhe Hasan Prishtina që u vendos te Salih Bajrami-Berisha.

- ^ "Gjurmime albanologjike: Seria e shkencave historike". Gjurmime Albanologjike. 11: 226. 1982.

- ^ a b Denisa Kostovicova (2005). Kosovo The Politics of Identity and Space. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415348065. Retrieved 8 August 2012.