Automixis[1] is the fusion of (typically haploid) nuclei or gametes derived from the same individual.[2] The term covers several reproductive mechanisms, some of which are parthenogenetic.[3]

Diploidy might be restored by the doubling of the chromosomes without cell division before meiosis begins or after meiosis is completed. This is referred to as an endomitotic cycle. This may also happen by the fusion of the first two blastomeres. Other species restore their ploidy by the fusion of the meiotic products. The chromosomes may not separate at one of the two anaphases (called restitutional meiosis) or the nuclei produced may fuse or one of the polar bodies may fuse with the egg cell at some stage during its maturation.

Some authors consider all forms of automixis sexual as they involve recombination. Many others classify the endomitotic variants as asexual and consider the resulting embryos parthenogenetic. Among these authors, the threshold for classifying automixis as a sexual process depends on when the products of anaphase I or of anaphase II are joined together. The criterion for "sexuality" varies from all cases of restitutional meiosis,[4] to those where the nuclei fuse or to only those where gametes are mature at the time of fusion.[3] Those cases of automixis that are classified as sexual reproduction are compared to self-fertilization in their mechanism and consequences.

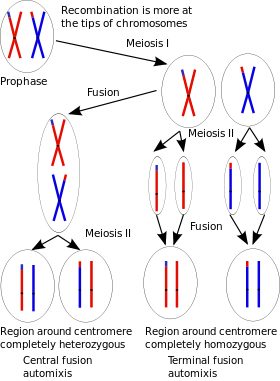

The genetic composition of the offspring depends on what type of apomixis takes place. When endomitosis occurs before meiosis[5][6] or when central fusion occurs (restitutional meiosis of anaphase I or the fusion of its products), the offspring get all[5][7] to more than half of the mother's genetic material and heterozygosity is mostly preserved[8] (if the mother has two alleles for a locus, it is likely that the offspring will get both). This is because in anaphase I the homologous chromosomes are separated. Heterozygosity is not completely preserved when crossing over occurs in central fusion.[9] In the case of pre-meiotic doubling, recombination -if it happens- occurs between identical sister chromatids.[5]

If terminal fusion (restitutional meiosis of anaphase II or the fusion of its products) occurs, a little over half the mother's genetic material is present in the offspring and the offspring are mostly homozygous.[10] This is because at anaphase II the sister chromatids are separated and whatever heterozygosity is present is due to crossing over. In the case of endomitosis after meiosis, the offspring is completely homozygous and has only half the mother's genetic material.

This can result in parthenogenetic offspring being unique from each other and from their mother.

Adaptive benefit of meiosis in automixis

editThe elements of meiosis that are retained in automixis in plants and animals are: (1) pairing of homologous chromosomes, (2) DNA double-strand break formation and (3) homologous recombinational repair at prophase I.[11] These features of meiosis are considered to be adaptations for repair of DNA damage.[11]

References

edit- ^ Engelstädter, Jan (2017). "Asexual but Not Clonal: Evolutionary Processes in Automictic Populations | Genetics". Genetics. 206 (2): 993–1009. doi:10.1534/genetics.116.196873. PMC 5499200. PMID 28381586. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- ^ "Automixis: Definition of Automixis by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Automixis". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 2020-12-11.[dead link]

- ^ a b Mogie, Michael (1986). "Automixis: its distribution and status". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 28 (3): 321–9. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1986.tb01761.x.

- ^ Zakharov, I. A. (April 2005). "Intratetrad mating and its genetic and evolutionary consequences". Russian Journal of Genetics. 41 (4): 402–411. doi:10.1007/s11177-005-0103-z. ISSN 1022-7954. PMID 15909911. S2CID 21542999.

- ^ a b c Cosín, Darío J. Díaz; Novo, Marta; Fernández, Rosa (2011). "Reproduction of Earthworms: Sexual Selection and Parthenogenesis". In Karaca, Ayten (ed.). Biology of Earthworms. Vol. 24. Springer. pp. 69–86. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-14636-7_5. ISBN 978-3-642-14636-7.

- ^ Cuellar, Orlando (1971-02-01). "Reproduction and the mechanism of meiotic restitution in the parthenogenetic lizard Cnemidophorus uniparens". Journal of Morphology. 133 (2): 139–165. doi:10.1002/jmor.1051330203. ISSN 1097-4687. PMID 5542237. S2CID 19729047.

- ^ Lokki, Juhani; Esko Suomalainen; Anssi Saura; Pekka Lankinen (1975-03-01). "Genetic Polymorphism and Evolution in Parthenogenetic Animals. Ii. Diploid and Polyploid Solenobia Triquetrella (lepidoptera: Psychidae)". Genetics. 79 (3): 513–525. doi:10.1093/genetics/79.3.513. PMC 1213290. PMID 1126629. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ^ Groot, T V M; E Bruins; J A J Breeuwer (2003-02-28). "Molecular genetic evidence for parthenogenesis in the Burmese python, Python molars bivittatus". Heredity. 90 (2): 130–135. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.578.4368. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800210. ISSN 0018-067X. PMID 12634818. S2CID 2972822.

- ^ Pearcy, M.; Aron, S; Doums, C; Keller, L (2004). "Conditional Use of Sex and Parthenogenesis for Worker and Queen Production in Ants" (PDF). Science. 306 (5702): 1780–3. Bibcode:2004Sci...306.1780P. doi:10.1126/science.1105453. PMID 15576621. S2CID 37558595.

- ^ Booth, Warren; Larry Million; R. Graham Reynolds; Gordon M. Burghardt; Edward L. Vargo; Coby Schal; Athanasia C. Tzika; Gordon W. Schuett (December 2011). "Consecutive Virgin Births in the New World Boid Snake, the Colombian Rainbow Boa, Epicrates maurus". Journal of Heredity. 102 (6): 759–763. doi:10.1093/jhered/esr080. PMID 21868391.

- ^ a b Mirzaghaderi G, Hörandl E (September 2016). "The evolution of meiotic sex and its alternatives". Proc Biol Sci. 283 (1838): 20161221. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.1221. PMC 5031655. PMID 27605505.