The Audiffred Building is a three-story historic commercial building in San Francisco, California, United States, formerly the location of waterfront bars and of the headquarters of a seamen's union, and now housing Boulevard restaurant. It is City of San Francisco Landmark number 7, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

Audiffred Building | |

| |

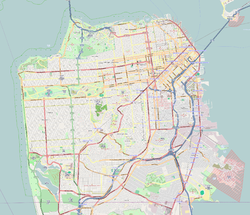

| Location | 100 The Embarcadero / 1–21 Mission St., San Francisco, California, US |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°47′36″N 122°23′29″W / 37.79333°N 122.39139°W |

| Area | 0.1 acres (0.040 ha) |

| Built | 1889 |

| Architect | Hippolite d'Audiffret; William Cullen |

| Architectural style | Second Empire |

| NRHP reference No. | 79000528 |

| Added to NRHP | May 10, 1979 |

Location

editThe Audiffred Building is on the corner of Mission Street and the Embarcadero, facing the waterfront;[1] it is one of the few surviving waterfront buildings on the land side of the Embarcadero. Since the removal of the elevated Embarcadero Freeway after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the building again looks out on the waterfront.[2]

Building

editThe building is of brick, with projecting brick quoins on the corners of the second floor. Its architecture emulates the Second Empire style of late 19th-century French commercial buildings.[2][3][4] There are three floors, the third being within a wood-framed tiled mansard roof decorated with a diamond pattern. The first floor has fluted cast iron columns with capitals incorporating a floral letter "A". Above the first floor on the eastern half of the facade is a frieze consisting of nautical motifs, including dolphins, lighthouses, sailing ships, and seahorses, in bas relief.[4][5]

History

editEarly years

editHippolite d'Audiffret (anglicized as "Audiffred"), a Frenchman who had been living in Mexico and reportedly walked to San Francisco from Veracruz after Emperor Maximilian and the French became unpopular there, and built a profitable business selling charcoal in Chinatown. The Audiffred Building was constructed for him in 1889,[2] presumably to house this business.[5] The first floor retail spaces were initially rented to a restaurant and three taverns;[3] at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries The Bulkhead tavern was one of these tenants, serving "Bull's Head" stew.

Upstairs until 1905 were the offices of the Coast Seamen's Union, later the Sailor's Union of the Pacific, a forerunner of the International Seamen's Union;[2][5] at one time or another prior to World War I the building also housed unions for Marine Engineers, Masters and Pilots, and Pile Drivers, and for a short time the Industrial Workers of the World.[3]

In an attempt to stop the fires following the 1906 earthquake, the San Francisco Fire Department nearly destroyed the building along with all those surrounding it; the Audiffred Building was saved when the bartender of the Bulkhead, the drinking establishment then occupying the building, bribed the firemen with the offer of two quarts of whiskey apiece and a fire cart full of bottles of wine.[2][3]

The Audiffred Building served as headquarters for the City Front strike in 1901[3] and again during the 1934 San Francisco waterfront strike, the strike committee was headquartered there.[6] On "Bloody Thursday" sailors Howard Sperry and Nick Bordoise were shot dead by police outside, as commemorated by a monument across the street.[2][3]

In 1928 one of the earliest branches of the Bank of Italy, forerunner of Bank of America, moved into part of the first floor; the nautical frieze was commissioned for the bank.

Artists

editWith the decline of San Francisco's waterfront in the mid-twentieth century, the Seven Seas Club for homeless sailors moved into the building in 1946,[3] and bohemian artists and writers including Elmer Bischoff, Howard Hack, Frank Lobdell, Hassel Smith, Martin Snipper, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti occupied lofts and studios on the two upper floors, which had no electricity,[7] until they were condemned as unsafe in 1955.[3] Ferlinghetti told The Paris Review (#228, Spring 2019 issue, p. 179) that he paid $29 a month in rent for his studio here where he made his first very tall paintings, that the only heating source was from a potbellied stove in one corner, and that the artists there could only work during the daytime because of the lack of electricity.

Fire

editIn 1978 a gas fire gutted the building, and it was to have been demolished; it was saved by public demand and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.[5][8] It was designated San Francisco City Landmark number 7 in 1968.[3][9]

Reconstruction and present day

editA domed penthouse was added in the reconstruction after the fire.[4] The building was subsequently bought by real estate developer Dusan Mills and in 1983–1984 was refurbished and remodeled into office space[10][11] by William E. Cullen.[12]

Since 1993, the Audiffred Building has housed Boulevard restaurant.[2][13][14][15][16]

References

edit- ^ Carl Nolte, "A trip down Mission, the most San Franciscan of streets", San Francisco Chronicle, November 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carl Nolte, "Every waterfront block has a story worth telling", San Francisco Chronicle, January 4, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Libby Ingalls, "Audiffred Building: Historical Essay", from Susan P. Sherwood and Catherine Powell, eds., The San Francisco Labor Landmarks Guide Book: A Register of Sites and Walking Tours, San Francisco: Labor Archives and Research Center, San Francisco State University, 2008,OCLC 299170392, Found SF, retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c Cindy Casey, "Architectural Spotlight: The Audiffred Building—A Tribute to France", Untapped Cities, December 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "National Register of Historic Places inventory—nomination form: The Audiffred Building", retrieved October 12, 2018. With 15 photos.

- ^ Peter Booth Wiley, National Trust Guide: San Francisco, New York: Preservation Press–Wiley, 2000, ISBN 9780471191209, pp. 221–22.

- ^ Bill Morgan, The Beat Generation in San Francisco: A Literary Tour, San Francisco: City Lights, 2003, ISBN 9780872864177, pp. 115–16.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ San Francisco Planning Code Article 10, "Preservation of Historical Architectural and Aesthetic Landmarks, Appendix A: Landmarks", retrieved November 28, 2018. Ingalls gives an incorrect year for the building's listing.

- ^ "Preserving Audiffred Building: a shrine, a victory, a dream", San Francisco Examiner, April 7, 1982, p. 95. (subscription required).

- ^ Valerie Brandt, "First Interstate Finances Preservation", California Preservation, October 1983, p. 3.

- ^ David Gebhard, Eric Sandweiss, and Robert Winter, The Guide to Architecture in San Francisco and Northern California, rev. ed. Salt Lake City, Utah: Peregrine Smith, 1985, ISBN 9780879052027, p. 66.

- ^ "Boulevard", Pat Kuleto Restaurant Development and Management, retrieved November 28, 2018.

- ^ Robert Selna, "Go green go tall", City Insider blog, San Francisco Chronicle, January 16, 2009.

- ^ "Food: Boulevard", San Francisco Chronicle, May 8, 2014, updated May 10, 2014 (subscription required).

- ^ "The most beautiful restaurants in SF", San Francisco Chronicle, accessed November 28, 2018.

External links

edit- Media related to Audiffred Building at Wikimedia Commons