Ashley Frederick Bryan (July 13, 1923 – February 4, 2022) was an American writer and illustrator of children's books. Most of his subjects are from the African-American experience. He was a U.S. nominee for the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 2006[1] and he won the Children's Literature Legacy Award for his contribution to American children's literature in 2009.[2] His picture book Freedom Over Me was short-listed for the 2016 Kirkus Prize and received a Newbery Honor.

Ashley Bryan | |

|---|---|

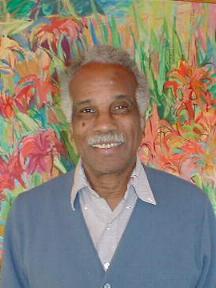

Ashley Bryan in 2007 | |

| Born | July 13, 1923 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | February 4, 2022 (aged 98) Sugar Land, Texas, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer, illustrator, teacher |

| Education | Cooper Union School of Art Columbia University University of Marseilles University of Freiburg |

| Period | 1950–2020 |

| Genre | children's picture books |

| Subject | African American studies |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | Children's Literature Legacy Award 2009 Virginia Hamilton Award 2012 |

Early years

editChildhood

editAshley Frederick Bryan was born on July 13, 1923, in Harlem and raised in the Bronx, both in New York City.[3] His father worked as a printer of greeting cards and loved birds, and Bryan remembered their apartment as full of a hundred birds.[3][4] He was born the second of six children and grew up with his three cousins. Bryan recalled his childhood in New York City during the 1930s as an idyllic time, full of art and music.[5] He learned to draw, paint, and play instruments at school from artists and musicians participating in the Work Projects Administration program.[5] With books he checked out from the library, Bryan made his own, temporary collection at home. He particularly enjoyed poetry, folktales, and fairy tales; stories that could be told within a brief span of pages.[6]

University studies and military service

editBryan attended the Cooper Union Art School, the only African-American student at that time. He had applied to other schools who had rejected him on the basis of race, but Cooper Union administered its scholarships in a blind test.[7]

At the age of nineteen, World War II interrupted his studies. He was drafted into the U.S. Army and assigned to serve in a segregated unit as a member of a Port Battalion, landing at Omaha Beach on D-Day. He was so ill-suited to this work that his fellow soldiers often encouraged him to step aside and draw. He always kept a sketch pad in his gas mask.[7] His book, Infinite Hope,[8] is an autobiographical journey during the war.

In 1946, he enrolled at Columbia University School of General Studies to study philosophy.[9] After the war, Bryan received a Fulbright Scholarship to study at the University of Marseille at Aix-en-Provence and later returning for two years to study at the University of Freiburg in Germany.[10]

Teaching career

editBryan taught art at Queen's College, Philadelphia College of Art, the Dalton School, Lafayette College, and Dartmouth College. He retired as emeritus professor of art at Dartmouth in 1988.[11][12]

Retirement and death

editIn the late 1980s, when Bryan retired from Dartmouth, he moved to Islesford, Maine, on Little Cranberry Island. He lived there until he moved to Sugar Land, Texas, where his niece lived, in 2019.[11][3]

The Ashley Bryan Center (501c3) was formed in 2013 to preserve, protect and care for Bryan's art, his collections, his books and to promote his legacy. In 2019, the Center and University of Pennsylvania reached an agreement to archive Bryan's works at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts.[13]

Bryan died at his niece's home on February 4, 2022, at the age of 98. He had congestive heart failure.[3][14]

Awards and honors

editBryan has received two American Library Association career literary awards for his "significant and lasting contributions", the 2009 Children's Literature Legacy Award and the 2012 King–Hamilton Award. The Children's Literature Legacy Award from the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) biennially recognizes one writer or illustrator of children's books published in the U.S. The committee named Dancing Granny, Beat the Story-Drum, Pum-Pum, and Beautiful Blackbird in particular and cited his "varied art forms".[2][15] The Coretta Scott King–Virginia Hamilton Award from the Ethnic & Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table (EMIERT) biennially recognizes one African-American writer or illustrator of children's or young-adult literature.[16][17] In 2008 Bryan was named a Literary Lion by The New York Public Library. In 2008, the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American History and Culture housed in the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library hosted the "Ashley Bryan Children's Literary Festival."[18] He also received the University of Southern Mississippi Medallion from the Fay B. Kaigler Children's Book Festival in 1994.[19]

For his lifetime work as a children's illustrator, Bryan was U.S. nominee in 2006 for the biennial, international Hans Christian Andersen Award, the highest recognition for creators of children's books.[1]

The Ashley Bryan Art series was established at the African American Research Library and Cultural Center of the Broward County Library in 2002. Dr.Henrietta M. Smith, Professor Emerita at the University of South Florida (USF) School of Information, worked with the Broward County Library to establish the children's book author and illustrator art series named for Ashley Bryan. Dr. Smith was also the lector for the 2003 Alice G. Smith Lecture, a lecture series held at the USF School of Information "to honor the memory of its first director, Alice Gullen Smith, known for her work with youth and bibliotherapy."[20] In 2012 the Ashley Bryan Art series celebrated ten years of exhibits and programs.[21] "The series began with Ashley Bryan submitting eight original art pieces to the library to serve as core of the art collection."[21] It became "a children's book author and illustrator series which has brought Coretta Scott King-Award winning authors and illustrators whose work reflected African culture to the library".[21] "The Ashley Bryan Art series has had a long-lasting cultural effect upon the community bringing children and families into the library and engaging youth with children’s book art and illustrations."[21]

Bryan was honored by Maine governor Janet Mills who proclaimed July 13, 2020 "Ashley Frederick Bryan Day" for his lifetime contributions to the state.[22][23]

Awards for particular works

editFor particular books he has been honored several times including multiple Coretta Scott King Awards and honors for illustration, the inaugural Lee Bennett Hopkins Poetry Award from the Pennsylvania State University, the Lupine Award from the Maine Library Association, and the Golden Kite Award for nonfiction.

- 1981, Coretta Scott King Award for illustration, Beat the Story Drum, Pum-Pum[24]

- 1983, Coretta Scott King Honor for illustration, I'm Going to Sing: Black American Spirituals[24]

- 1987, Coretta Scott King Honor for writing and illustration, Lion and the Ostrich Chicks and Other African Folk Tales[24]

- 1988, Coretta Scott King Honor for illustration, What a Morning! The Christmas Story in Black Spirituals[24]

- 1992, Coretta Scott King Honor for illustration, All Night, All Day: A Child's First Book of African American Spirituals[24]

- 1993, Lee Bennett Hopkins Poetry Award, Lupine Award, Sing to the Sun[25][26]

- 1998, Coretta Scott King Honor for illustration, Ashley Bryan's ABC of African American Poetry[24]

- 2004, Coretta Scott King Award for illustration, Beautiful Blackbird[24]

- 2008, Coretta Scott King Award for illustration, Let it Shine: Three Favorite Spirituals[24]

- 2010, Golden Kite Award for nonfiction, Ashley Bryan: Words to My Life's Song[27]

- 2017, Newbery Honor, Coretta Scott King Honor for writing and illustration, Lupine Award for picture book, Kirkus Prize for Young Readers' Literature finalist, Freedom Over Me: Eleven Slaves, Their Lives and Dreams Brought to Life by Ashley Bryan[17][26][28][29]

- 2020, Carter G. Woodson Book Award, Coretta Scott King Award for illustration, Infinite Hope: A Black Artist’s Journey from World War II to Peace[30][31]

Works

editBibliography

edit- Black Boy by Richard Wright (1950)[11]

- Fabliaux: Ribald Tales from the Old French translated by Robert Hellman and Richard O'Gorman (1965)[32]

- Moon, For What Do You Wait? Poems by Rabindranath Tagore (1967)[32]

- The Ox of the Wonderful Horns and Other African Folktales (1971)[12]

- Walk Together Children: Black American Spirituals Vol 1 (1974)[32]

- The Adventures of Aku (1976)[12]

- The Dancing Granny (1977)[12]

- I Greet the Dawn: Poems by Paul Laurence Dunbar (1978)[32]

- Jethro and the Jumbie by Susan Cooper (1979)[32]

- Jim Flying High by Mari Evans (1979)[32]

- Beat the Story-Drum, Pum-Pum (1980)[12]

- I’m Going to Sing: Black American Spirituals Vol 2 (1982)[24]

- The Cat’s Purr (1985)[12]

- Lion and the Ostrich Chicks and Other African Folk Poems (1986)[12]

- What a Morning: The Christmas Story in Black Spirituals by John Langstaff (1987)[24]

- Sh-Ko and his Eight Wicked Brothers illustrated by Fumio Yoshimura (1988)[32]

- Turtle Knows Your Name (1989)[32]

- Pourquoi Tales: The Cat's Purr, Why Frog and Snake Never Play Together, the Fire Bringer with Margaret Hodges (1989)[32]

- All Night, All Day: A Child’s First Book of African-American Spirituals (1991)[12]

- Climbing Jacob’s Ladder by John Langstaff (1991)[32]

- Sing to the Sun (1992)[12]

- Christmas Gif’: An Anthology of Christmas Poems, Songs and Stories Written by and About African-Americans by Charemae Rollins (1993)[32]

- The Story of Lightning and Thunder (1993, 1999)[32]

- What a Wonderful World by George David Weiss and Bob Thiele (1995)[32]

- It's Kwanzaa Time! by Linda and Clay Goss (1995)[32]

- The Story of the Three Kingdoms by Walter Dean Myers (1995)[32]

- The Sun Is So Quiet: Poems by Nikki Giovanni (1996)[32]

- Ashley Bryan’s ABC of African American Poetry (1997, 2001)[24][32]

- Carol of the Brown King: Nativity Poems by Langston Hughes (1998)[32]

- The House with No Door: African Riddle-Poems by Brian Swann (1998)[32]

- Ashley Bryan’s African Tales, Uh Huh (1998)[12]

- Why Leopard Has Spots, Dan Stories from Liberia by Won-Ldy Paye and Margaret H. Lippert (1998)[32]

- The Night Has Ears: African Proverbs (1999)[32]

- Aneesa Lee and the Weaver’s Gift by Nikki Grimes (1999)[32]

- Jump Back, Honey: The Poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar, co-illustrators Carole Byard, Jan Spivey Gilchrist, Jerry Pinkney, and Faith Ringgold (1999)[32]

- How God Fix Jonah by Lorenz Graham (2000)[32]

- Salting the Ocean: 100 Poems by Young Poets by Naomi Shahab Nye (2000)[32]

- Beautiful Blackbird (2003)[12]

- A Nest Full of Stars by James Berry (2004)[32]

- Let It Shine: Three Favorite Spirituals (2007)[24]

- My America by Jan Spivey Gilchrist, co-illustrator (2007)[32]

- Ashley Bryan: Words to My Life's Song (2009)[27]

- All Things Bright and Beautiful by Cecil Alexander (2010)[12]

- Who Built the Stable? (2012)[12]

- Can’t Scare Me! (2013)[12]

- Ashley Bryan’s Puppets: Making Something From Everything (2014)[33]

- By Trolley Past Thimbledon Bridge illustrated by Marvin Bileck (2015)[34]

- Sail Away by Langston Hughes (2015)[3]

- Freedom Over Me: Eleven Slaves, Their Lives and Dreams Brought to Life (2016)[26]

- I Am Loved by Nikki Giovanni (2018)[10]

- Blooming Beneath the Sun by Christina Rossetti (2019)[35]

- Infinite Hope: A Black Artist’s Journey from World War II to Peace (2020)[31]

Filmography

edit- I Know a Man ... Ashley Bryan (2016) - dir. Richard Kane[36]

Stage works

editAmerican composer Alvin Singleton composed Sing to the Sun, a commissioned work for the 1995-1996 season by a consortium of five musical festivals. The work consisted of a chamber orchestra made up of an oboe, clarinet, viola, piano and percussion,[37] children's voices and a narrator, and drew upon the collection of poems by Bryan entitled: Sing to the Sun: Poems and Pictures. Bryan himself narrated the premiere and all the following performances.[38]

On June 10, 2017 the world premiere of Alliance Theatre’s production Dancing Granny took place at the Oglethorpe University's Conant Performing Arts Center in Atlanta, Georgia.[39] The musical play was adapted for the stage from Bryan's book of the same name with music composed by Jireh Breon Holder and choreography by Ameenah Kaplan.[40][41]

In 2018, Bryan collaborated with composer Aaron Robinson on an African-American requiem titled A Tender Bridge; a 90-minute, 13 movement work that celebrates Bryan's life and career based on his writings that uses "jazz, ragtime, Negro spirituals, Southern hymns and other musical idioms, along with a full choir, gospel choir, children’s choir, orchestra jazz ensemble and multiple narrators."[42][43]

In April 2021, Alliance Theatre also staged Beautiful Blackbird Live, based on the children's book by Bryan, Beautiful Blackbird. The concert version tells the story about five birds that have flown from Africa to sing about how beautiful it is to be black.[44][45]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b

"IBBY Announces the Winners of the Hans Christian Andersen Awards 2006". International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY). Press release March 27, 2006.

"Hans Christian Andersen Awards". IBBY. Retrieved 2013-07-23. - ^ a b "Welcome to the (Laura Ingalls) Wilder Award home page!". Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). American Library Association (ALA). 2009. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Risen, Clay (February 9, 2022). "Ashley Bryan, Who Brought Diversity to Children's Books, Dies at 98". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ Dlouhy, Caitlyn (August 3, 2015). "Profile of 2009 Wilder Award winner Ashley Bryan". The Horn Book Magazine. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Gold, Donna (December 1997 – January 1998). "Ashley Bryan's World". American Visions. 12 (6): 31. ISSN 0884-9390.

- ^ Marcus, Leonard S. (2002). Ways of Telling: Conversations on the Art of the Picture Book. New York, NY: Dutton Children's Books. pp. 18–31. ISBN 0-525-46490-5.

- ^ a b "Ashley Bryan Center || Ashley's Timeline". ashleybryancenter.org. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ Bryan, Ashley (2019). Infinite hope : a Black artist's journey from World War II to peace (First ed.). New York. ISBN 978-1-5344-0490-8. OCLC 1097366206.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ ""Make Me Brave for Life"". Columbia Magazine. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ a b "Ashley Bryan Center || Home". ashleybryancenter.org. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c Smith, Harrison (February 8, 2022). "Ashley Bryan, whose joyous picture books celebrated Black life and history, dies at 98". Washington Post. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Ashley Bryan | Pennsylvania Center for the Book". Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ Trotter, Bill (February 2, 2019). "Collection of artifacts by Maine artist finds out-of-state home". Bangor Daily News.

- ^ "Ashley Bryan, prize-winning children's author, illustrator, dies at 98". NBC News. February 6, 2022.

- ^

"Laura Ingalls Wilder Award, Past winners". ALSC. ALA.

"About the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award". ALSC. ALA. Retrieved 2013-03-10. - ^ "Ashley Bryan 2012 recipient of the Coretta Scott King-Virginia Hamilton Award for Lifetime Achievement". Press release January 23, 2012. ALA. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ a b "Coretta Scott King Book Awards". ALA. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ "Atlanta-Fulton Hosts Children's Festival". Georgia Library Quarterly. 45 (2). July 1, 2008. ISSN 2157-0396.

- ^ "Past Medallion Recipients". University of Southern Mississippi. Archived from the original on August 1, 2016.

- ^ Smith, Alice Gullen. 1989. "Will the real bibliotherapist please stand up?." Journal of Youth Services in Libraries 2, 241-249.

- ^ a b c d Gómez, E. (2012). "Broward County Library Celebrates Ten Years of the Ashley Bryan Art Series". Children & Libraries. 10 (1): 18–19.

- ^ Arnold, Willis Ryder (July 14, 2020). "Mills Declares 'Ashley Bryan Day' To Honor 97-Year-Old Artist And Author". Maine Public. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Green, Alex (July 16, 2020). "Maine Declares Ashley Bryan Day". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Coretta Scott King Book Award — All Recipients, 1970–Present". ALA. April 5, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ "About the Lee Bennett Hopkins Poetry Award | Pennsylvania Center for the Book". Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Lupine Award Winners". Maine Library Association. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ a b "Past Golden Kite Recipients". Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ "American Library Association announces 2017 youth media award winners" (Press release). American Library Association. January 30, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ "2016 Kirkus Prize". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "Carter G. Woodson Book Award and Honor Winners". socialstudies.org. National Council for the Social Studies. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ a b Keyes, Bob (January 28, 2020). "Ashley Bryan and Daniel Minter win national youth book awards".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Bryan, Ashley (1923 - )". Maine State Library. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ "Children's Book Review: Ashley Bryan's Puppets: Making Something From Everything". Publishers Weekly. May 19, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "By Trolley Past Thimbledon Bridge". Kirkus Reviews. February 16, 2015. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "Children's Book Review: Blooming Beneath the Sun". Publishers Weekly. February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "I Know A Man...Ashley Bryan - Presented by Gene Siskel Film Center". The University of Chicago. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ Gresham, Mark (November 18, 1995). "Sing To The Sun" (PDF). Vibes. Atlanta: Atlanta.CreativeLoafing.Com. p. 89. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ Thrash Murphy, Barbara (August 14, 2014). Black Authors and Illustrators of Books for Children and Young Adults. USA: Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 978-0415762731.

- ^ Baldowski, Bill (June 3, 2017). "'Dancing Granny' kicking off Alliance's 2017-18 season". Northside Neighbor. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ News Desk, BWW (May 5, 2017). "Alliance to Premiere Beloved Children's Story, THE DANCING GRANNY". Broadway World. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ Watts, Gabbie (June 2, 2017). "Alliance Theatre Adapts 'The Dancing Granny' For The Stage". WABE 90.1. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ Keyes, Bob (August 12, 2018). "Ashley Bryan, 95, 'always honored' to have a new show". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ Nestor, Argy (October 22, 2018). "A Tender Bridge". Maine Arts Ed. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ Kenneavy, Shelley (June 1, 2021). "Beautiful Blackbird Live Celebrates Diversity Through Music". www.wabe.org. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Henry Fuller, Sally (April 9, 2021). "First Look: BEAUTIFUL BLACKBIRD LIVE Begins Run at the Alliance Theatre". encoreatlanta.com. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- "Ashley Bryan". Gale Literary Databases Contemporary Authors Online. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2009. (subscription required)

External links

edit- I Know a Man ... Ashley Bryan at IMDb

- Ashley Bryan's Wish

- Ashley Bryan Papers, Special Collections at the University of Southern Mississippi (de Grummond Children's Literature Collection)