This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

Arthur Louis Aaron, VC, DFM (5 March 1922 – 13 August 1943) was a Royal Air Force pilot in the Second World War. He flew 90 operational flying hours and 19 sorties,[not verified in body] and was awarded with the Distinguished Flying Medal and (posthumously) the Victoria Cross.

Arthur Louis Aaron | |

|---|---|

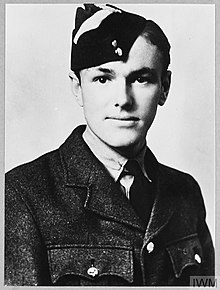

Military photograph of Aaron | |

| Born | 5 March 1922 Leeds, England |

| Died | 13 August 1943 (aged 21) Bône, French Algeria |

| Buried | Annaba, Algeria |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service | Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1941–1943 |

| Rank | Flight Sergeant |

| Service number | 1458181 |

| Unit | No. 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron RAF |

| Battles / wars | Second World War

|

| Awards | |

Early life and wartime service

editAaron was a native of Leeds, Yorkshire, and was educated at Roundhay School and Leeds School of Architecture. When the Second World War started in 1939, Aaron joined the Air Training Corps squadron at Leeds University. The following year he volunteered to train as aircrew in the Royal Air Force. He trained as a pilot in the United States at No. 1 British Flying Training School at Terrell Municipal Airport in Terrell, Texas. Aaron completed his pilot training on 15 September 1941 and returned to England to train at an Operation Conversion Unit before he joined No. 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron RAF, flying Short Stirling heavy bombers from RAF Downham Market.[citation needed]

His first operational sortie was a mining sortie[definition needed] in the Bay of Biscay, but he was soon flying missions over Germany. On one sortie, his Stirling was badly damaged, but he completed his bombing run and returned to England. His actions were rewarded with a Distinguished Flying Medal.[1]

VC action

editAaron, 21 years old, was flying Stirling serial number EF452 on his 20th sortie. Nearing the target, his bomber was struck by machine gun fire. The bomber's Canadian navigator (Cornelius A. Brennan) was killed, and other members of the crew were wounded.[citation needed]

The official citation for his VC reads:[2]

Air Ministry, 5th November, 1943.

The King has been graciously pleased to confer the Victoria Cross on the undermentioned airman in recognition of most conspicuous bravery:—

1458181 Acting Flight Sergeant Arthur Louis Aaron, D.F.M., Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, No. 218 Squadron (deceased).

On the night of 12 August 1943, Flight Sergeant Aaron was captain and pilot of a Stirling aircraft detailed to attack Turin. When approaching to attack, the bomber received devastating bursts of fire from an enemy fighter. Three engines were hit, the windscreen shattered, the front and rear turrets put out of action and the elevator control damaged, causing the aircraft to become unstable and difficult to control. The navigator was killed and other members of the crew were wounded.

A bullet struck Flight Sergeant Aaron in the face, breaking his jaw and tearing away part of his face. He was also wounded in the lung and his right arm was rendered useless. As he fell forward over the control column, the aircraft dived several thousand feet. Control was regained by the flight engineer at 3,000 feet. Unable to speak, Flight Sergeant Aaron urged the bomb aimer by signs to take over the controls. Course was then set southwards in an endeavour to fly the crippled bomber, with one engine out of action, to Sicily or North Africa.

Flight Sergeant Aaron was assisted to the rear of the aircraft and treated with morphia. After resting for some time he rallied and, mindful of his responsibility as captain of aircraft, insisted on returning to the pilot's cockpit, where he was lifted into his seat and had his feet placed on the rudder bar. Twice he made determined attempts to take control and hold the aircraft to its course but his weakness was evident and with difficulty he was persuaded to desist. Though in great pain and suffering from exhaustion, he continued to help by writing directions with his left hand.

Five hours after leaving the target the petrol began to run low, but soon afterwards the flare path at Bone airfield was sighted. Flight Sergeant Aaron summoned his failing strength to direct the bomb aimer in the hazardous task of landing the damaged aircraft in the darkness with undercarriage retracted. Four attempts were made under his direction; at the fifth Flight Sergeant Aaron was so near to collapsing that he had to be restrained by the crew and the landing was completed by the bomb aimer.

Nine hours after landing, Flight Sergeant Aaron died from exhaustion. Had he been content, when grievously wounded, to lie still and conserve his failing strength, he would probably have recovered, but he saw it as his duty to exert himself to the utmost, if necessary with his last breath, to ensure that his aircraft and crew did not fall into enemy hands. In appalling conditions he showed the greatest qualities of courage, determination and leadership and, though wounded and dying, he set an example of devotion to duty which has seldom been equalled and never surpassed.

The gunfire that hit Aaron's aircraft was thought to have been from an enemy night fighter, but may have been friendly fire from another Stirling.[3] Because of that the initial plan was to award him the George Cross, but prime minister Winston Churchill changed it to the Victoria Cross, because he did not want the enemy to know the RAF had shot down one of its own aircraft.[4]

Memorials

editThis section needs to be updated. The reason given is: the Jewish Military Museum has closed. (June 2023) |

He was an 'old boy' of Roundhay School, Leeds (headmaster at the time was B. A. Farrow). There is a plaque in the main hall of the school to his memory incorporating the deed that merited the VC. On 5 March 2022 (Aaron's 100th birthday) a Yorkshire Society blue plaque was unveiled at Roundhay School in memory of Aaron.[citation needed]

To mark the new millennium, Leeds Civic Trust organised a public vote to choose a statue to mark the occasion, and to publicise the city's past heroes and heroines. Candidates included Benjamin Henry Latrobe and Henry Moore. Arthur Aaron won the vote, with Don Revie beating Joshua Tetley and Frankie Vaughan as runner-up. Located on a roundabout on the eastern edge of the city centre, close to the West Yorkshire Playhouse, the statue of Aaron was unveiled on 24 March 2001 by Malcolm Mitchem, the last survivor of the aircraft. The five-metre bronze sculpture by Graham Ibbeson takes the form of Aaron standing next to a tree, up which are climbing three children progressively representing the passage of time between 1950 and 2000, with the last a girl releasing a dove of peace, all representing the freedom his sacrifice helped ensure.[5] There was controversy about the siting of the statue, and it was proposed to transfer it to Millennium Square outside Leeds City Museum.[6] However, as of 2012[update] the statue remains on the roundabout.[7]

Aaron's Victoria Cross and other medals are kept at Leeds City Museum.[8]

Controversially (), he was commemorated at the AJEX Jewish Military Museum in Hendon, London,[9] as one of three known Jewish Victoria Cross recipients of the Second World War (the others being Thomas William Gould,[10] Royal Navy, and John Kenneally, Irish Guards). Aaron may have belonged at school or University to 319 ATC (Jewish) Squadron in Broughton, Salford, where his photograph still hangs, according to Col Martin Newman DL from the HQ Air Cadets archives.[citation needed]

Genealogical controversy

editGenealogical research carried out in 2018–2019 by David Rattee shows Arthur Louis Aaron was baptised a Roman Catholic on 15 October 1922 at St. Mary's Church, Knaresborough, North Yorkshire.[11] The baptism record is held in the archives of Ampleforth Abbey Trust. Aaron's father Benjamin gave his own religion as Church of England on his WWI army records. Aaron's parents, Benjamin Aaron and Rosalie Marie Aaron (née Marney) were married on 8 February 1919 at Addingham Parish Church, near Ilkley. Benjamin Aaron was born on 29 June 1891 at 29 Dewsbury Road, Hunslet, Leeds, West Yorkshire, and baptised on 2 August 1891 at St Mary the Virgin, Hunslet Parish Church, Leeds. Birth, baptism, marriage, death, census records and other published period documentation trace the paternal surname back to William Aaron (b. 1802 Hillam, near Sherburn-in-Elmet, d. 27 September 1877) and Faith Harrison (27 August 1796 – 1 June 1866) of Sherburn, North Yorkshire. Aaron was a common surname in Yorkshire well before Jewish immigration to Leeds began.[11]

It has been stated that Aaron's father was a Russian Jewish immigrant, even though the family denied it after Aaron was killed, giving him a Roman Catholic memorial service; it has also been claimed that he boasted of being Jewish to members of his air training colleagues in the mess in Texas on many occasions.[12] A possible cause of the confusion, of which there is no traceable documentation, is that Aaron may have been taken to be Jewish before his death due to his name, and/or passed himself as Jewish in Leeds, or in the RAF.[11]

References

edit- ^ "No. 36215". The London Gazette (Supplement). 19 October 1943. p. 4620.

- ^ "No. 36235". The London Gazette (Supplement). 5 November 1943. p. 4859.

- ^ Bowyer (1980). The Stirling Bomber. p. 129.

- ^ For Gallantry: Medals Expert Discusses the George Cross | TEA & MEDALS, with military historian Mark Smith, Sep 2, 2021

- ^ "The Arthur Aaron Statue". Leeds Civic Trust. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ "Brave Arthur deserves his pride of place". Yorkshire Evening Post. 1 November 2007.

- ^ "Arthur Louis Aaron" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ Hammett, Jessica (18 September 2017). "Arthur Louis Aaron: A WW2 Hero From Leeds". Leeds Museums & Galleries. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ "VC: Pilot Aaron, Hit In The Face & Slowly Bleeding To Death Helped His Crew Fly The Plane Home". 29 April 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ "Victoria Cross". The Jewish Museum London. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Sugarman, P. (2022). "Assumed and mistaken Jewishness: Arthur Louis Aaron VC DFM". Shemot (Journal of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain). 30 (2): 9–10.

- ^ Morris, Henry; Sugarman, Martin (2011). We Will Remember Them. Vallentine Mitchell.