This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2013) |

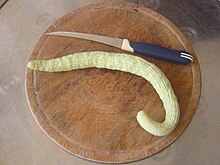

The Armenian cucumber,[1] Cucumis melo Flexuosus Group or Cucumis melo var. flexuosus, is a type of long, slender fruit which tastes like a cucumber and looks somewhat like a cucumber inside. It is actually a variety of true melon (C. melo), a species closely related to the cucumber (C. sativus). It is also known as the yard-long cucumber, snake cucumber, snake melon, Varunk in Armenian, chanbar in Persian, sheng in Semnani, chirimenhosonagauri in Japanese, acur in Turkish, kakadee in Hindi, tar in Punjabi, قثاء in Arabic, commarella or tortarello in Italian. It should not be confused with the snake gourds (Trichosanthes spp.). The skin is very thin, light green, and bumpless. It has no bitterness and the fruit is almost always used without peeling. It is also sometimes called a gutah.[2]

| Armenian cucumber | |

|---|---|

| |

| Species | Cucumis melo |

| Cultivar group | Flexuosus Group |

Description

editThe Armenian cucumber grows approximately 75 to 90 centimetres (30 to 36 in) long. It grows equally well on the ground or on a trellis. The plants prefer to grow in full sun for most of the day. The fruit is most flavorful when it is 30 to 40 centimetres (12 to 15 in) long. Pickled Armenian cucumber is sold in Middle Eastern markets as "pickled wild cucumber".[3]

History

editFredric Hasselquist, in his travels in Asia Minor, Egypt, Cyprus and Syria in the 18th century, came across the "Egyptian or hairy cucumber, Cucumis chate", commonly known today in Egypt as "atta" (classical قِثَّاء or قُثَّاء (qiṯṯāʾ or quṯṯāʾ). It is today included in the Armenian variety. It is said by Hasselquist to be the “queen of cucumbers, refreshing, sweet, solid, and wholesome.” He also states “they still form a great part of the food of the lower-class people in Egypt serving them for meat, drink and physic.” George E. Post, in Hastings' Dictionary of the Bible, states, “It is longer and more slender than the common cucumber, being often more than a foot long, and sometimes less than an inch thick, and pointed at both ends.”

As indicated by images from Roman times, C. melo subsp. melo Chate Group had been the stem from which longer fruits were selected very early, hence both the qishu’im of 10th to 6th century BC Israel and the cucumis of the 1st century CE Roman writers Columella[4] and Pliny[5] were mostly C. melo subsp. melo Flexuosus Group.[6][7] These vegetable melons are by far the cucurbit most frequently encountered in ancient Mediterranean images and texts, and hence must have been a widely grown and esteemed crop.[7]

According to Pliny the Elder, the Emperor Tiberius had the cucumber on his table daily during summer and winter. In order to have it available for his table every day of the year, the Romans reportedly used artificial methods of growing (similar to the greenhouse system), whereby mirrorstone refers to Pliny's lapis specularis, believed to have been sheet mica.[8][9]

"Indeed, he was never without it; for he had raised beds made in frames upon wheels, by means of which the cucumbers were moved and exposed to the full heat of the sun; while, in winter, they were withdrawn, and placed under the protection of frames glazed with mirrorstone."

— Pliny the Elder, Natural History XIX.xxiii, "Vegetables of a Cartilaginous Nature—Cucumbers. Pepones"

Reportedly, they were also cultivated in specularia, cucumber houses glazed with oiled cloth.[8] Pliny describes the Italian fruit as very small, probably like a gherkin. He also describes the preparation of a medication known as elaterium.[10] However, some scholars believe that he was instead referring to Ecballium elaterium, known in pre-Linnean times as Cucumis silvestris or Cucumis asininus ('wild cucumber' or 'donkey cucumber'), a species different from the common cucumber. Pliny also writes about several other varieties of cucumber, including the cultivated cucumber,[11] and remedies from the different types (9 from the cultivated; 5 from the "anguine;" and 26 from the "wild").

Charlemagne had Cucumis grown in his gardens in the 8th/9th century.

A study published in 2018 concluded that melon yields in Israel can be improved by selection of local landraces. The study examined landraces collected from 42 fields, finding extensive variations in certain traits that could be cultivated to improve the local production.[12]

References

edit- ^ "Armenian Cucumber". Have A Plant. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ^ Leon Kaye (10 September 2012). "In One Picture: Armenian Cucumbers Rule The Valley". greengopost.com.

- ^ [1] Wild Cucumbers Got You In a Pickle?

- ^ Forster and Heffner 1955

- ^ Rackham 1950

- ^ Janick et al.2007

- ^ a b Paris, Harry; Janick, Jules (2008), "Reflections on linguistics as an aid to taxonomical identification of ancient Mediterranean cucurbits: the Piqqus of the Faqqous1", in M. Pitrat (ed.), Cucurbitaceae, I.N.R.A., Avignon, France., pp. 43–51

- ^ a b James, Peter J.; Thorpe, Nick; Thorpe, I. J. (1995). "Ch. 12, Sport and Leusure: Roman Gardening Technology". Ancient Inventions. Ballantine Books. p. 563. ISBN 978-0-345-40102-1

- ^ Pliny the Elder. [77–79 AD] 1855. "Vegetables of a Cartilaginous Nature—Cucumbers. Pepones." Ch. 23 in The Natural History XIX, translated by J. Bostock and H. T. Riley. London: Taylor & Francis. – via Perseus under PhiloLogic, also available via Perseus Project.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History XX.iii

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History XX.iv-v

- ^ Omari, Samer; Kamenir, Yuri; Benichou, Jennifer I. C.; Pariente, Sarah; Sela, Hanan; Perl-Treves, Rafael (2018). "Landraces of snake melon, an ancient Middle Eastern crop, reveal extensive morphological and DNA diversity for potential genetic improvement". BMC Genetics. 19 (1): 34. doi:10.1186/s12863-018-0619-6. PMC 5966880. PMID 29792158.