Aqua Claudia ("the Claudian water") was an ancient Roman aqueduct that, like the Aqua Anio Novus, was begun by Emperor Caligula (37–41 AD) in 38 AD and finished by Emperor Claudius (41–54 AD) in 52 AD.[1]

It was the eighth aqueduct to supply Rome and together with Aqua Anio Novus, Aqua Anio Vetus and Aqua Marcia, it is regarded as one of the "four great aqueducts of Rome".[2]

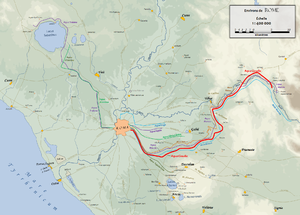

Route

editIts mainsprings, the Caeruleus and Curtius, were situated near the 38th milestone of the Via Sublacensis[3][4]: 150 .

The total length was approximately 69 kilometres (43 mi)[3], most of which was underground[citation needed]. The flow was about 185,000 m3 (6,500,000 cu ft) in 24 hours -- ca. 2.3 m3/s (80 cu ft/s)[3]. Directly after its filtering tank, near the seventh mile of the Via Latina, it finally emerged onto arches, which increase in height as the ground falls toward the city, reaching over 30 metres (100 ft)[citation needed].

It is one of the two ancient aqueducts that flowed through the Porta Maggiore, the other being the Aqua Anio Novus[4]: 150 . It is described in some detail by Frontinus in his work published in the later 1st century, De aquaeductu[3][4]: 150 .

Nero extended the aqueduct with the Arcus Neroniani from (Spes Vetus on) the Esquiline hill to the Caelian hill[5] and Domitian further extended it to the Palatine[6], after which the Aqua Claudia could provide all 14 Roman districts with water[5]. The section on the Caelian hill was called arcus Caelimontani[5].

Bridges

editVisible remaining bridges include the Ponte sul Fosso della Noce, Ponte San Antonio, Ponte delle Forme Rotte, Ponte dell`Inferno, Ponte Barucelli.

Ponte dell`Inferno

editThe bridge has a single arch in opus quadratum, reinforced in the late period in brickwork. The specus (channel) is about 1 m wide and is also built in opus quadratum, but with a very porous stone which is locally found as a layer immediately above the tuff on which the bridge rests.

Ponte Barucelli

editThe Ponte Barucelli (also known as Ponte Diruto) is made up of two monumental bridges 8 m apart for the aqua Claudia (to the north) the Anio Novus (to the south) to cross the Acqua Nera stream. Both date to between 38 and 52 AD. They were later strengthened with buttresses and reinforcements, becoming two huge continuous and connected structures.

The Anio Novus bridge, about 85 m long and about 10 m wide, has a few small arches except for the main high and narrow one for the Acqua Nera. It had originally been built of tuff in opus quadratum. In the second half of the 1st century it was reinforced in opus mixtum, visible at the two east end buttresses. At the beginning of the 3rd century nine rectangular buttresses were added at regular intervals on the north side while on the south side only three were added near the bed of the stream, later increased by five on the west bank in poor opus latericium and two on the east in opus mixtum.

Later the two bridges were connected by three brick arches and with buttresses.

Repairs

editThe aqueduct went through at least two major repairs. Tacitus suggests that the aqueduct was in use by AD 47.[7] An inscription from Vespasian suggests that Aqua Claudia was used for ten years, then failed and was out of use for nine years.[8] The first repair was done by Emperor Vespasian in 71 AD; it was repaired again in 81 AD by Emperor Titus[3]. Additionally, brick stamps from 123 AD testify to some restorations during the rule of emperor Hadrian[3].

Alexander Severus reinforced the arches of Nero (CIL VI.1259) where they are called arcus Caelimontani, including the line of arches across the valley between the Caelian and the Palatine[5].

The church of San Tommaso in Formis was later built into the side of the aqueduct.

Gallery

edit-

The Arcus Nerioniani near the Caelian and the Palatine Hills.

See also

edit- Aqua Alexandrina – Roman aqueduct, a landmark of Rome, Italy

- List of aqueducts in the city of Rome

- List of aqueducts in the Roman Empire

- List of Roman aqueducts by date

- Ancient Roman engineering

- Ancient Roman technology

Notes

edit- ^ Frontinus. De aquaeductu. 1.13.

- ^ Blackman, Deane R. (1978). "The Volume of Water Delivered by the Four Great Aqueducts of Rome". Papers of the British School at Rome. 46: 52–72. doi:10.1017/S0068246200011417. JSTOR 40310747. S2CID 129034821.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Schram, Wilke D. (January 2010). "Aqua Claudia". Roman Aqueducts. Archived from the original on 2 December 2024. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Smith, William; Wayte, William; Marindin, G. D., eds. (1890). "Aquaeductus". A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. Vol. 1. Albemarie St.: John Murray.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Platner, Samuel Ball (1929). "Arcus Neroniani". In Ashby, Thomas (ed.). A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 40–41.

- ^ "The Aqueducts". Maquettes Historiques. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Georges, K. E. (1874-01-01). "Tac. Ann. 11, 23". Philologus. 33 (1–4): 311. doi:10.1524/phil.1874.33.14.311. ISSN 2196-7008. S2CID 164564689.

- ^ Christol, Michel (1981). "Doubles lyonnais d'inscriptions romaines de Narbonne (CIL, XIII, 1994 = CIL, XII, 4486 ; CIL, XIII, 1982 a = CIL, XII, 4497)". Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise. 14 (1): 221–224. doi:10.3406/ran.1981.1068. ISSN 0557-7705.

External links

edit- Interactive map with the full Aqua Claudia

- Map of Rome with Aqua Claudia running (red)

- The Aqua Claudia Webpage

- 3D digital model of Rome featuring Aqua Claudia

- Lucentini, M. (31 December 2012). The Rome Guide: Step by Step through History's Greatest City. Interlink. ISBN 9781623710088.

Media related to Aqua Claudia at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Aqua Anio Vetus |

Landmarks of Rome Aqua Claudia |

Succeeded by Cloaca Maxima |