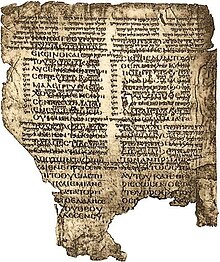

The AqBurkitt (also: Trismegistos nr: 62108,[1][2] Taylor-Schechter 12.184[3] + Taylor-Schechter 20.50[3] = Taylor-Schlechter 2.89.326, vh074,[4] t050,[4] LDAB 3268[2]) are fragments of a palimpsest containing a portion of the Books of Kings from Aquila's translation of the Hebrew bible from the 6th century, overwritten by some liturgical poems of Yannai dating from the 9–11th century.[5] This Aquila translation was performed approximately in the early or mid-second century C.E.[6] The manuscript is variously dated to the 6th-century CE,[3][7] or 5th-6th century CE.[8][9]

History

editA lot of manuscripts were found in the Cairo Geniza in Egypt and these palimpsest fragments were brought to Cambridge by Solomon Schechter.[10] AqBurkitt was published by Francis Crawford Burkitt (this is where the name comes from) in Fragments of the Books of Kings According to the Translation of Aquila (1897).[11] Burkitt concludes that the manuscript is indisputably Jewish because it comes from the Geniza, and because the Jews at the time of Justinian used the Aquila version.[12] On the other hand, it has been argued that the scribe who copied it was a Christian.[13][citation needed]

Description

editThere are preserved "separate pairs of conjugate vellum leaves" of the manuscript (bifolium).[12] Each leaf is 27 cm (11 in) tall by 44 cm (17 in) wide.

Aquila's text

editAquila's text is badly preserved.[14] It has been written in two columns and 23 or 24 lines per page[15] and contains parts of 1 Kings 20:7–17[16][a] and 2 Kings 23:11–27[3][b] (3 Kings xxi 7–17 and 4 Kings xxiii 11–27 according to Septuagint numbering). This palimpsest is written in koine Greek language, in bold uncial letters, without capital letters at beginnings or paragraphs or as the first letter of the pages.[15] This is one of the few fragments that preserve part of the translation of Aquila, which has also been found in a few hexaplaric manuscripts.[17]

Tetragrammaton and nomina sacra

editThe tetragrammaton is written in paleo-Hebrew script characters ( ) in following places: 1 Kings 20:13, 14; 2 Kings 23:12, 16, 21, 23, 25, 26, 27.[18][19] The rendering of the letters yod and waw are generally identical and the sign used for it is a corruption of both letters.[20][21][8] In one instance, where there was insufficient space at the end of a line, the tetragrammaton is given by κυ,[22][23][3] the nomen sacrum rendering of the genitive case of Κύριος[24] which is unique in the Genizah manuscripts.[25]

AqBurkitt has used to argue for the reception history of Aquila's translation among Jews or to the use of nomina sacra by Jews.[26] In an article focused on the topic, Edmon L. Gallagher concludes that there is no certainty about whether it was a Jew or a Christian who transcribed AqBurkitt, and thus it cannot be used as evidence in these debates.[27]

Yannai's text

editThe upper text is a liturgical work of Yannai written in Hebrew. This work contains Qerovot/Qerobot poems on four sedarim in Leviticus (13:29; 14:1; 21:1; 22:13), "which can be joined with other leaves in the Genizah to make a complete quire".[5] The text was dated to 11th century C.E. by Schechter,[12][3] but it may be older, even to the ninth century.[5]

Actual location

editThis fragment is currently stored in the University of Cambridge Digital Library.[5]

See also

edit- AqTaylor

- Hexapla

- Papyrus Rylands 458 the oldest manuscripts

- Septuagint manuscripts

Notes

edit- ^ Gallagher (2013, p. 3) says 1 Kings 21:7-17

- ^ Turner (1911, p. 856) says 2 Kings 23:12-17

Citations

edit- ^ Papyri.info.

- ^ a b Trismegistos.

- ^ a b c d e f Gallagher 2013, p. 3.

- ^ a b Kraft 1999.

- ^ a b c d University of Cambridge Digital Library.

- ^ Labendz 2009, p. 353.

- ^ Orsini 2018.

- ^ a b Tov 2018, p. 220.

- ^ Papaconstantinou 2022, p. 85.

- ^ Schürer, Vermes & Millar 2014, p. 497.

- ^ Howard 1977, p. 73.

- ^ a b c Burkitt 1897, p. 9.

- ^ Gallagher 2013, p. 2.

- ^ Marcos 2001, p. 113.

- ^ a b Burkitt 1897, p. 10.

- ^ Turner 1911, p. 856.

- ^ Britannica 2011.

- ^ Andrews 2016, p. 23.

- ^ Ortlepp 2010, p. 191.

- ^ Burkitt 1897, p. 15.

- ^ Tov, Kraft & Parsons 1990, p. 13.

- ^ Hurtado 2006, p. 109.

- ^ Trobisch 2000, p. 113.

- ^ Gallagher 2013, pp. 3, 20–26.

- ^ Gallagher 2013, p. 11.

- ^ Gallagher 2013, pp. 8–22.

- ^ Gallagher 2013, p. 25-26.

References

edit- Andrews, Edward D. (2016). The Complete Guide to Bible Translation: Bible Translation Choices and Translation Principles. Christian Publishing House. ISBN 9780692728710.

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia (2011-09-22). "Aquila". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-01-23.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia (16 August 2024). "Early versions". Encyclopedia Britannica.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Burkitt, Francis Crawford (1897). Fragments of the Books of Kings According to the Translation of Aquila. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 1117070484. OCLC 5222981.

- Gallagher, Edmon (2013). "The Religious Provenance of the Aquila Manuscripts from the Cairo Genizah". Journal of Jewish Studies. 64 (2): 283–305. doi:10.18647/3141/JJS-2013.

- Howard, George (March 1977). "The Tetragram and the New Testament" (PDF). Journal of Biblical Literature. 96 (1). The Society of Biblical Literature: 63–83. doi:10.2307/3265328. JSTOR 3265328.

- Hurtado, Larry (2006). The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802828958.

- Jellicoe, Sidney (April 1969). Israel, Abrahams; Montefiore, Claude Goldsmid (eds.). "Review: Aquila and His Version. Reviewed Work: An Index to Aquila. Greek-Hebrew, Hebrew-Greek, Latin-Hebrew, with the Syriac and Armenian Evidence by Joseph Reider, Nigel Turner". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 59 (4). University of Pennsylvania Press: 326–332. doi:10.2307/1453471. JSTOR 1453471.

- Kraft, Robert A. (1999-07-12). "Chronological List of Early Papyri and MSS for LXX/OG Study (plus the same MSS in Canonical Order appended)". Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- Labendz, Jenny R. (2009-07-01). "Aquila's Bible Translation in Late Antiquity: Jewish and Christian Perspectives" (PDF). Harvard Theological Review. 102 (3): 353–388. doi:10.1017/S0017816009000832. JSTOR 40390021. S2CID 162547482.

- Marcos, Natalio Fernández (2001-11-06). Watson, Wilfred (ed.). The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible. Biblical Studies and Religious Studies. BRILL. ISBN 978-03-91-04109-7.

- Orsini, Pasquale (2018). Studies on Greek and Coptic Majuscule Scripts and Books. Studies in Manuscript Cultures. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-057559-0.

- Ortlepp, S. (2010). Introduction to the Interlinear Bible. Author. ISBN 978-1-4452-7789-9.

- Papaconstantinou, Arietta (16 October 2022). "Lifting the cloak of invisibility: Identifying the Jews of late antique Egypt" (PDF). In Brand, Mattias; Scheerlinck, Eline (eds.). Religious Identifications in Late Antique Papyri: 3rd—12th Century Egypt (PDF). London: Routledge. pp. 69–91. doi:10.4324/9781003287872-5. ISBN 978-1-003-28787-2. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- Papyri.info. "Trismegistos 62108 = LDAB 3268". Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- Schürer, Emil; Vermes, Geza; Millar, Fergus (2014). The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ: Volume 3.i. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567604521.

- Tov, E. (2018). Scribal Practices and Approaches Reflected in the Texts Found in the Judean Desert. Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah. Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-1434-6.

- Tov, E.; Kraft, R.A.; Parsons, P.J. (1990). The Greek Minor Prophets Scroll from Nahal Hever (8HevXIIgr): The Seiyal Collection I. Discoveries in the Judaean desert. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826327-2.

- Toy, Crawford Howell; Burkitt, F. C.; Ginzberg, Louis (1909). "AQUILA (Ακύλας)". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- Trismegistos. "TM 62108 / LDAB 3268". Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- Trobisch, David (2000). The First Edition of the New Testament. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195112405.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-195-11240-5. OCLC 827708997.

- Turner, Cuthbert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 849–894.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- University of Cambridge Digital Library. "Palimpsest; Bible; piyyuṭ (T-S 20.50)". Cambridge University Press.