Annulment is a legal procedure within secular and religious legal systems for declaring a marriage null and void.[1] Unlike divorce, it is usually retroactive, meaning that an annulled marriage is considered to be invalid from the beginning almost as if it had never taken place.[a][2] In legal terminology, an annulment makes a void marriage or a voidable marriage null.[3]

Void vs voidable marriage

editA difference exists between a void marriage and a voidable marriage.

A void marriage is a marriage that was not legally valid under the laws of the jurisdiction where the marriage occurred, and is void ab initio. Although the marriage is void as a matter of law, in some jurisdictions an annulment is required to establish that the marriage is void or may be sought in order to obtain formal documentation that the marriage was voided. Under the laws of most nations, children born during a void marriage are considered legitimate. Depending upon the jurisdiction, reasons for why a marriage may be legally void may include consanguinity (incestual marriage), bigamy, group marriage, or child marriage.[4][5]

A voidable marriage is a marriage that can be canceled at the option of one of the parties. The marriage is valid, but may be annulled if contested in court by one of the parties to the marriage. The petition to void the marriage must be brought by one of the parties to the marriage, and a voidable marriage thus cannot be annulled after the death of one of the parties. A marriage may be voidable for a variety of reasons, depending on jurisdiction. Common reasons for allowing a party to void a marriage include entry into the marriage as a result of threat or coercion. Some jurisdictions have a distinction between legal age of majority and legal age of marriage; in this case, it is usually the custom that the marriage can proceed with parental or guardian consent, and the marital parties being able to ratify or void the marriage upon reaching the age of majority. These are also considered voidable marriages.

The principal difference between a void and voidable marriage is that, as a void marriage is invalid from the beginning, no legal action is required to set the marriage aside. A marriage may be challenged as void by a third party, for example in probate proceedings during which a party to the void marriage is claiming inheritance rights as a spouse. In contrast, a voidable marriage may be ended only through the judgment of a court, and may be voided only upon the petition of one of the parties to the marriage or, if a party is under a legal disability, by a third party representative such as a parent or legal guardian.

The legal distinction between void and voidable marriages can be significant in relation to forced marriage. In a jurisdiction that classifies forced marriages as void, then the state can cancel the marriage even against the will of the spouses. In contrast, if the law provides that a forced marriage is voidable then, even if it can be proved that the marriage was forced, the state cannot act to end the marriage in the absence of an application by a spouse.[6]

Christianity

editCatholicism

editIn the canon law of the Catholic Church, an annulment is properly called a "Declaration of Nullity", because according to Catholic doctrine, the marriage of baptized persons is a sacrament and, once consummated and thereby confirmed, cannot be dissolved as long as the parties to it are alive. A "Declaration of Nullity" is not dissolution of a marriage, but merely the legal finding that a valid marriage was never contracted. This is analogous to a finding that a contract of sale is invalid, and hence, that the property for sale must be considered to have never been legally transferred into another's ownership. A divorce, on the other hand, is viewed as returning the property after a consummated sale.

The Pope may dispense from a marriage ratum sed non consummatum since, having been ratified (ratum) but not consummated (sed non-consummatum), it is not absolutely unbreakable. A valid natural marriage is not regarded as a sacrament if at least one of the parties is not baptized. In certain circumstances it can be dissolved in cases of Pauline privilege[7] and Petrine privilege,[8] but only for the sake of the higher good of the spiritual welfare of one of the parties.

The Church holds the exchange of consent between the spouses to be the indispensable element that "makes the marriage". The consent consists in a "human act by which the partners mutually give themselves to each other": "I take you to be my wife" – "I take you to be my husband." This consent that binds the spouses to each other finds its fulfillment in the two "becoming one flesh". If consent is lacking there is no marriage. The consent must be an act of the will of each of the contracting parties, free of coercion or grave external fear. No human power can substitute for this consent. If this freedom is lacking the marriage is invalid. For this reason (or for other reasons that render the marriage null and void) the Church, after an examination of the situation by the competent ecclesiastical tribunal, can declare the nullity of a marriage, i.e., that the marriage never existed. In this case the contracting parties are free to marry, provided the natural obligations of a previous union are discharged. – Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1626–1629

Although an annulment is thus a declaration that "the marriage never existed", the Church recognizes that the relationship was a putative marriage, which gives rise to "natural obligations". In canon law, children conceived or born of either a valid or a putative marriage are considered legitimate,[9] and illegitimate children are legitimized by a putative marriage of their parents, as by a valid marriage.[9]

Certain conditions are necessary for the marriage contract to be valid in canon law. Lack of any of these conditions makes a marriage invalid and constitutes legal grounds for a declaration of nullity. Accordingly, apart from the question of diriment impediments dealt with below, there is a fourfold classification of contractual defects: defect of form, defect of contract, defect of willingness, defect of capacity. For annulment, proof is required of the existence of one of these defects, since canon law presumes all marriages are valid until proven otherwise.[10]

Canon law stipulates canonical impediments to marriage. A diriment impediment prevents a marriage from being validly contracted at all and renders the union a putative marriage, while a prohibitory impediment renders a marriage valid but not licit. The union resulting is called a putative marriage. An invalid marriage may be subsequently convalidated, either by simple convalidation (renewal of consent that replaces invalid consent) or by sanatio in radice ("healing in the root", the retroactive dispensation from a diriment impediment). Some impediments may be dispensed from, while those de jure divino (of divine law) may not be dispensed.

In some countries, such as Italy, in which Catholic Church marriages are automatically transcribed to the civil records, a Church declaration of nullity may be granted the exequatur and treated as the equivalent of a civil divorce.

Independent Catholicism

editAnnulments are granted by certain Independent Catholic denominations, such as the Evangelical Catholic Church.[11]

Anglicanism

editThe Church of England, the mother church of the worldwide Anglican Communion, historically had the right to grant annulments, while divorces were "only available through an Act of Parliament."[12] Examples in which annulments were granted by the Anglican Church included being under age, having committed fraud, using force, and lunacy.[12]

Certain Continuing Anglican denominations, such as the Anglican Catholic Church, offer annulments, which are granted by the bishop.[13][14]

Methodism

editMethodist Theology Today, edited by Clive Marsh, states that:

when ministers say, "I pronounce you husband and wife," they not only announce the wedding—they create it by transforming the bride and groom into a married couple. Legally they are now husband and wife in society. Spiritually, from a sacramental point of view, they are joined together as one in the sight of God. A minute before they say their vows, either can call off the wedding. After they say it, the couple must go through a divorce or annulment to undo the marriage.[15]

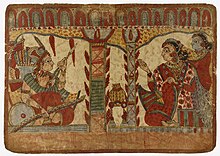

Islam

editFaskh means "to annul" in Islam.[3] It is a Sharia-granted procedure to judicially rescind a marriage.[citation needed]

A man does not need grounds to divorce his wife in Islam. To divorce, he can simply invoke Talaq and part with the dower he gave her before marriage; alternatively, he can invoke the Lian doctrine in case of adultery, either by bringing four witnesses who saw the wife committing adultery or by self-testifying and swearing by Allah four times. Sharia law then requires the court to grant the divorce requested by the man. Talaq is controversial, though it is a widely held belief, the Qu'ran insists counseling between two parties is necessary first before considering divorce when there is dissention/contention between spouses (Qu'ran 4:35). The marriage contract clauses agreed upon must be honored when divorce is invoked.[3][16]

Also, Sharia does grant a Muslim woman simple ways to end her marital relationship and without declaring the reason. Faskh or (kholo) (annulment) doctrine specifies certain situations when a Sharia court can grant her request and annul the marriage.[3][not specific enough to verify]

Grounds for Faskh are:[3][17] (a) irregular marriage (fasid),[18] (b) forbidden marriage (batil),[19] (c) the marriage was contracted by non-Muslim husband who adopted Islam after marriage,[citation needed][20] (d) the husband or wife became an apostate after marriage, (e) husband is unable to consummate the marriage. In each of these cases, the wife must provide four independent witnesses acceptable to the Qadi (religious judge), who has the discretion to declare the evidence unacceptable.[16]

In Sunni Maliki school of jurisprudence (fiqh), cruelty, disease, life-threatening ailment and desertion are additional Sharia approved grounds for the wife or the husband to seek annulment of the marriage.[3] In these cases too, the wife must provide two male witnesses or one male and two female witnesses or in some cases four witnesses,[17] acceptable to the Qadi (religious judge), who has the discretion to declare the evidence unacceptable.[citation needed]

In certain circumstances, an unrelated Muslim can petition a Qadi to void (faskh) the marriage of a Muslim couple who may not want the marriage to end. For example, in case the third party detects apostasy from Islam by either husband or wife (through blasphemy, failure to respect Sharia, or conversion of husband or wife or both from Islam to Christianity, etc.).[17] In cases of apostasy, in addition to annulment of the marriage, the apostate may face additional penalties such as death sentence, imprisonment and civil penalties unless they repent and return to Islam.[21][not specific enough to verify]

Civil law

editAustralia

editSince 1975, Australian law provides only for void marriages. Before 1975, there were both void and voidable marriages. Today, under the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth.) a decree of nullity can only be made if a marriage is void.[22]

A marriage is void if:[23][24][25]

- one or both of the parties were already married at the time (i.e. bigamy)

- the parties are in a prohibited relationship (i.e. closely related such as siblings)

- the parties did not comply with the marriage laws in the jurisdiction where they were married (note that although a marriage contracted abroad is in general considered valid in Australia, in certain cases, such as when there are serious contradictions with the marriage laws of Australia, the marriage is void)

- one or both of the parties were under-age and did not have the necessary approvals, (minimum marriageable age is 16, but 16- and 17-years-olds need special court approval) or

- one or both of the parties were forced into the marriage.

England and Wales

editEngland and Wales provides for both void and voidable marriages.[5]

- Void marriage

- Spouses are closely related

- One of the spouses was under 16

- One of the spouses was already married or in a civil partnership

- Voidable marriage

- Non-consummation

- No proper consent to entering the marriage (forced marriage)

- The other spouse had a sexually transmitted disease at the time of marriage

- The woman was pregnant by another man at the time of marriage

Section 13 of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 provides for certain restrictions in regard to the possibility of annulling voidable marriages, including where the petitioner knew of the "defect" and of the possibility of annulment, but induced the respondent to believe that the petitioner would not seek an annulment; or where it would be "unjust" to the respondent to grant the decree of nullity. There is usually a time limit of three years from the date of the marriage in order to institute the proceedings.[26]

France

editIn France, a country of Roman Catholic tradition, annulment features prominently in law, and can be obtained for many reasons. The law provides for both void and voidable marriages.[27] (see articles 180 to 202, and articles 144, 145, 146, 146–1, 147, 148, 161, 162, 163, and 164 of the French Civil Code)

- void marriage: forced marriage (not to be confused with consent obtained under deception which makes a marriage voidable not void); underage marriage; bigamy; incestuous marriage; lack of legal competence of the registrar; and clandestine marriage (i.e. hiding the marriage from the public, no witnesses present)

- voidable marriage: vices of consent, i.e. consent obtained under deception/by misrepresentation of one's personal characteristics, personal past, intentions after marriage, etc., where the deceived spouse discovers after the marriage the deceit (given a very broad interpretation by the courts); and failure to secure the authorization of the person who should have authorized the marriage (i.e. lack of authorization of guardians of a mentally challenged spouse)

Philippines

editDivorce is mostly not available as a legal method to dissolve marriage in the Philippines. To most of the Filipino population, annulment is the only legal recourse to dissolve marital unions. Muslims who married under Islamic rites can divorce.

The annulment process and prerequisite under Philippine civil law are defined under the Family Code of the Philippines.[28] Under Philippine civil law, "annulment" and "declaration of nullity" are legally distinct.

Annulments are considered valid until the point of termination, hence children conceived or born before termination are considered legitimate.[29]

This contrasts to a declaration of nullity, where a marital union is rendered a void marriage or never valid from the beginning.[29][30]

Annulments granted by religious institutions including the Roman Catholic church, the majority Christian denomination in the Philippines, does not legally void marriages. Married couples still have to seek civil annulment.[28][31]

United States

editIn the United States, the laws governing annulment are different in each state. Although the grounds for seeking an annulment differ, as can factors that may disqualify a person for an annulment, common grounds for annulment include the following:

- Marriage between close relatives. States typically prohibit marriages between a parent and child, grandparent and grandchild, or between siblings, and many restrict marriages between first cousins.

- Mental incapacity. A person who is not legally capable of consenting to marriage based upon mental illness or incapacity, including incapacity caused by intoxication, may later seek an annulment.

- Underage marriage. If one or both spouses are below the legal age to marry, then the marriage is subject to being annulled.

- Duress. A person who enters a marriage due to threats or force may later seek an annulment.

- Fraud. A spouse is tricked into marrying the other spouse, through the misrepresentation or concealment of important facts about the other spouse, such as a criminal record, pregnancy by another man, or infection with a sexually transmitted disease.[32]

- Bigamy. One spouse was already married at the time of the marriage for which annulment is sought.

For some grounds of annulment, such as concealment of infertility, if after discovering the potential basis for an annulment a couple continues to live together as a married couple, that reason may be deemed forgiven. For underage marriages, annulment must typically be sought while the underage spouse remains a minor, or shortly after that spouse reaches the age of majority, or the issue is deemed waived.[33]

Arizona

editIn Arizona, a "voidable" marriage is one in which there is "an undissolved prior marriage, one party being underage, a blood relationship, the absence of mental or physical capacity, intoxication, the absence of a valid license, duress, refusal of intercourse, fraud, and misrepresentation as to religion."[34][35]

Illinois

editIn Illinois, an annulment is a judicial determination that a valid marriage never existed. One of the parties must file with the court a petition for invalidity of marriage. There are four grounds for annulment in Illinois:

- Inability to consent to marriage, for example as a result of mental disability, intoxication, force, duress or fraud;

- One spouse cannot have sexual intercourse, with that fact being unknown to the other spouse at the time of marriage;

- One spouse was under the age of 18, and married without the consent of a parent, legal guardian, or court; and

- The marriage was illegal, such as in the case of bigamy or certain close blood relationships.[36]

Nevada

editIn Nevada, annulment is available when: a marriage that was void at the time performed (such as blood relatives, bigamy), lacked consent (such as, underage, intoxication, insanity), or is based on some kind of dishonesty.[37]

A couple who was married in Nevada will qualify to file for annulment in that state, no matter where they live at the time of filing.[38] Those who were married outside Nevada must establish residency by living there for a minimum of six weeks before filing.[39]

New York

editNew York law provides for: Incestuous and void marriages (DRL §5); Void marriages (DRL §6) Voidable marriages (DRL §7).[40]

The cause of action for annulment of a voidable marriage in New York State is generally fraud (DRL §140 (e)). There are other arguments.[41] Fraud generally means the intentional deception of the Plaintiff by the Defendant in order to induce the Plaintiff to marry. The misrepresentation must be substantial in nature, and the Plaintiff's consent to the marriage predicated on the Defendant's statement. The perpetration of the fraud (prior to the marriage), and the discovery of the fraud (subsequent to the marriage) must be proven by corroboration of a witness or other external proof, even if the Defendant admits guilt (DRL §144). The time limit is three years (not one year). This does not run from the date of the marriage, but the date the fraud was discovered, or could reasonably have been discovered.[42]

Annulments may also be granted to a spouse under the age of 18, where marriage occurred without lawful parental consent or court approval, where a party lacked the mental capacity to consent to marriage, where one of the parties lacked the physical capacity to consummate the marriage and the other was not aware of that disability at the time of marriage, or for incurable mental illness for a period of five years or more.[43]

A bigamous marriage (one where one party was still married at the time of the second marriage) as well as an incestuous marriage is void ab initio (not legal from its inception). However, there is still the need for an "Action to Declare the Nullity of a Void Marriage" (DRL §140 (a)), upon which the Court, after proper pleadings, renders a judgment that the marriage is void. There may be effects of marriage such as a property settlement and even maintenance if the court finds it equitable to order such relief.[44]

Wisconsin

editIn Wisconsin, the possible requirements for annulment include: bigamy, incest, or inducing the bride to be married under duress (see Shotgun marriage).[45] Marriages may also be nullified due to one or more of the parties being: underage, intoxicated, or being mentally unsound.[46]

Marriages may also be nullified due to fraud from one or more of three categories: defendant, marriage witness(es), or marriage officiant. Any misrepresentation by those three parties, including but not limited to lying about: status as officiant, ability to perform the ceremony, age of the participants or witnesses, felony status or current marriage status of either member of the married couple can be grounds for an annulment on the basis of fraud. Fraud in this cases is prosecuted under Wisconsin Law 943.39[47] as a Class H felony.

Multiple annulments for Henry VIII

editHenry VIII of England had three of his six marriages annulled.[48][49][50][51] These marriages were to Catherine of Aragon (on the grounds that she had already been married to his brother—although this annulment is not recognized by the Catholic Church); Anne Boleyn[51] (not wishing to execute his legal wife, he offered her an easy death if she would agree to an annulment); and Anne of Cleves[52] (on the grounds of non-consummation of the marriage and the fact that she had previously been engaged to someone else). Catherine Howard never had her marriage annulled. She had committed adultery with Thomas Culpeper during the marriage, and she had flirted with members of his court. Because of this, on November 22, 1541, it was proclaimed at Hampton Court that she had "forfeited the honour and title of Queen," and was from then on to be known only as the Lady Catherine Howard. Under this title she was executed for high treason three months later.[53]

Controversies

editThe grounds of annulment in regard to a voidable marriage, and indeed the concept of a voidable marriage itself, have become controversial in recent years. According to a paper in Singapore Academy of Law Journal:[54]

- "Where divorce is available to all, it seems somewhat inconsistent to favour some groups of unhappily married people by giving them the privilege of choosing whether to put an end to their misery by way of annulment or by way of divorce. It is also worthy of note that some judges, like Coomaraswamy J. in Chua Ai Hwa (mw), have noted that some of the grounds making a marriage voidable have tended to be abused by parties who hope the court will grant the petition on fairly skimpy evidence simply because the petition is not defended."

See also

edit- Alimony

- Catholic marriage theology

- Nullity (conflict) for a discussion of the rules relating to the annulment of marriage (conflict) in the conflict of laws

- Separation

Notes

edit- ^ Though some jurisdictions provide that the marriage is only void from the date of the annulment; for example, this is the case in section 12 of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 in England and Wales

References

edit- ^ Statsky, William (1996). Statsky's Family Law: The Essentials. Delmar Cengage Learning. pp. 85–86. ISBN 1-4018-4827-3.

- ^ "Report on Family Law (Scot Law Com No 135, 1992)". Scitlawcom.gov.uk.

See paragraph 8.23."In English law a decree of nullity in respect of a voidable marriage now has prospective effect only. It operates "to annul the marriage only as respects any time after the decree has been made absolute, and the marriage shall, notwithstanding the decree, be treated as if it has existed up to that time.""

- ^ a b c d e f John L. Esposito (2002), Women in Muslim Family Law, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0815629085, pp. 33–34

- ^ "Legislative Information – LBDC". Public.leginfo.state.ny.us.

- ^ a b "Annul a marriage – GOV.UK". Gov.uk.

- ^ Scutt, Jocelynne (25 September 2014). "Human Rights, 'Arranged' Marriages and Nullity Law: Should Culture Override or Inform Fraud and Duress?". The Denning Law Journal. 26: 62–97. doi:10.5750/dlj.v26i0.935 – via ubplj.org.

- ^ 1 Corinthians 7:10–15

- ^ Orlando O. Espín, James B. Nickoloff (editors), An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies (Liturgical Press 2007 ISBN 978-0-81465856-7), p. 1036

- ^ a b "Code of Canon Law – IntraText". Vatican.va. 15 July 2013. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Code of Canon Law – IntraText". Vatican.va. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Citywide Community Church devoted to inclusivity, peace, social justice". Rock Valley Publishing Newspapers. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ a b Kertzer, David I.; Barbagli, Marzio (2002). The History of the European Family: Family life in the long nineteenth century (1789–1913). Yale University Press. p. 116. ISBN 9780300090901.

- ^ Marriage services, St. Matthew the Apostle Traditional Anglican Church

- ^ "Transferring to the ministry in the Anglican Catholic Church". Anglican Catholic Church. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ Marsh, Clive (10 May 2006). Methodist Theology Today. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 126. ISBN 9780826481047.

- ^ a b J Rehman (2007), The sharia, Islamic family laws and international human rights law: Examining the theory and practice of polygamy and talaq, International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 21(1): 108–127

- ^ a b c Lynn Welchman (2000), Beyond the Code: Muslim Family and the Shari'a Judiciary in the Palestinian West Bank, Springer, ISBN 978-9041188595, pp. 311–318

- ^ For example, a marriage when the Muslim woman was observing Iddah or Ihram

- ^ For example, a married couple that is biologically related father-daughter, mother-son, sister-brother. Quran 4:23; Consanguineous marriages are very common in Islamic world – Consanguineous marriages Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine Brecia Young, Santa Fe Institute, United States (2006)

- ^ Quran forbids marriage of Muslim woman to a Christian, Jew, Hindu, Buddhist, Atheist or other non-Muslim man, Quran 2:221

- ^ Peters & De Vries (1976), Apostasy in Islam, Die Welt des Islams, Vol. 17, Issue 1/4, pp 1–25

- ^ Dickey, A. (2007) Family Law (5th Ed)

- ^ "Home – Federal Circuit Court of Australia". Familylawcourts.gov.au. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Home – Federal Circuit Court of Australia" (PDF). Familylawcourts.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ al, Sally Cole et (8 January 2015). "Family law" (PDF). State Library of NSW.

- ^ "Matrimonial Causes Act 1973". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Code civil". Legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ a b Bordey, Hana (31 March 2023). "Padilla files bill recognizing civil effect of church decreed annulment". GMA News. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Divorce and annulment in the Philippines: An explainer". Cebu Daily News. 30 May 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ "What's the difference between annulment, legal separation, and divorce?". GMA News. 17 February 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ Quisimorio, Ellson. "'Significant development' on bill simplifying annulment of marriage hailed". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ G. B. C (June 1929). "Marriage: Annulment for Fraudulent Misrepresentation as to Intent to Cohabit G. B. C.". Michigan Law Review. 27 (8): 934–936. doi:10.2307/1280381. JSTOR 1280381.; See also Smith v. Smith, 171 Mass. 404, 409 (1898).

- ^ "Grounds for Annulment" (PDF). TexasLawHelp.org. Pro Bono Net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Family Law Questions & Answers". AZLawHelp. Legal Services Corporation. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Annulment Form Criteria". AzCourtHelp. Arizona Bar Foundation. 31 October 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "I Want My Marriage Annulled". ILAO. Illinois Legal Aid Online. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Illinois Legal Aid Online". Family Law Self-Help Center. Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Differences Between Annulment & Divorce". Family Law Self-Help Center. Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Marjorie Paslov; Ashton, Patrick (March 2018). "Fact Seet: Residency Requirements in Nevada" (PDF). Nevada State Legislature. Legislative Counsel Bureau. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "New York Consolidated Laws, Domestic Relations Law – DOM – FindLaw".

- ^ "Legislative Information – LBDC". Public.leginfo.state.ny.us. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Annulment". New York City Bar. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Divorce Information & Frequently Asked Questions". NYCourts.gov. New York State Unified Court System. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Declaration of Nullity". New York City Bar. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Wisconsin Legislature: 767.313". docs.legis.wisconsin.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ Foley, John P. (May 1966). "The Voidable Void Marriage in Wisconsin". Marquette Law Review. 49 (4): 751. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Wisconsin Legislature: 943.38 Annotation". docs.legis.wisconsin.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ "The Trial of Sir Thomas More: A Chronology". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on 2007-05-26. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ "Anne of Cleves: Facts, Information, Biography & Portraits". Englishhistory.net. 31 January 2015. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Anne of Cleves: Rejected Fourth Wife of Henry VIII". Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ a b "Anne Boleyn". Tudorhistory.org. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Anne of Cleves". Tudorhistory.org. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "FindArticles.com – CBSi". Findarticles.com. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-12. Retrieved 2014-09-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)