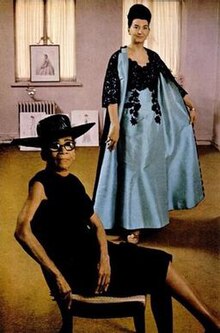

Ann Cole Lowe (December 14, 1898 – February 25, 1981) was an American fashion designer. Best known for designing the ivory silk taffeta wedding dress worn by Jacqueline Bouvier when she married John F. Kennedy in 1953, she was the first African American to become a noted fashion designer.[1] Lowe's designs were popular among upper class women for five decades from the 1920s through the 1960s.

Ann Lowe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Ann Cole Lowe December 14, 1898 Clayton, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | February 25, 1981 (aged 82) Queens, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Annie Cohen Anne Lowe |

| Alma mater | S. T. Taylor Design School |

| Occupation | Fashion designer |

| Years active | 1919–1972 |

| Known for | Wedding dress of Jacqueline Bouvier |

| Children | 2 |

Early life

editLowe was born in rural Clayton, Alabama in 1898[2] to Jane and Jack Lowe.[3] She was the great granddaughter of an enslaved woman and an Alabama plantation owner.[4] She had an older sister, Sallie.[5] Ann attended school in Alabama until she dropped out at the age of 14.[3] Lowe's interest in fashion, sewing and designing came from her mother Janey and grandmother Georgia,[6] both of whom were seamstresses. They ran a dressmaking business that was often frequented by the first families of Montgomery and other members of high society.[7] Lowe's mother died when Lowe was 16 years old. At this time, Lowe took over the family business.[8][9]

Personal life

editLowe was married twice and had two children. She married her first husband, Lee Cohen, in 1912. They had a son, Arthur Lee, who later worked as Lowe's business partner until his death from a car accident[1][6] in 1958.[10] Lowe left Cohen because he opposed her having a career.[5][9] Arthur Lee would go on to become Lowe's business partner until 1958.[1]

She married for a second time, to Caleb West,[3] but that marriage also ended. Lowe later said, "My second husband left me. He said he wanted a real wife, not one who was forever jumping out of bed to sketch dresses."[11] Lowe later adopted a daughter, Ruth Alexander.[1]

In the 1930s, Lowe lived in an apartment on Manhattan Avenue in Harlem. Her older sister Sallie later lived with her. Both were members of St. Mark's United Methodist Church.[5]

Career

editIn 1917, Lowe and her son moved to New York City, where she enrolled at S. T. Taylor Design School.[1] As the school was segregated, Lowe was required to attend classes in a room alone.[11] However, segregation did not stop her, and she still managed to rise above her peers in school. Her work was often shown to her white peers in recognition of her outstanding artistry, and she was eligible for graduation after attending school for only half a year.[12] After graduating in 1919, Lowe and her son moved to Tampa, Florida. The following year, she opened her first dress salon. The salon catered to members of high society and quickly became a success.[13] Having saved $20,000 from her earnings, Lowe returned to New York City in 1928.[14] During the 1950s and 1960s, she worked on commission for stores such as Henri Bendel, Montaldo's, I. Magnin, Chez Sonia, Neiman Marcus, and Saks Fifth Avenue.[1][13][15] In 1946, she designed the dress that Olivia de Havilland wore to accept the Academy Award for Best Actress for To Each His Own, although the name on the dress was Sonia Rosenberg.[4]

As she was not getting credit for her work, Lowe and her son opened a second salon, Ann Lowe's Gowns, in New York City on Lexington Avenue in 1950.[9][13][14] Her one-of-a-kind designs made from the finest fabrics were an immediate success and attracted many wealthy, high-society clients.[13] Design elements for which she was known include fine handwork, signature flowers, and trapunto technique.[16] Her signature designs are what helped her eventually become recognized for her work. In 1964, the Saturday Evening Post later called Lowe "society's best kept secret" and in 1966, Ebony magazine referred to her as "The Dean of American Designers.[1][10][15] Throughout her career, Lowe was known for being highly selective in choosing her clientele. She later described herself as "an awful snob", adding: "I love my clothes and I'm particular about who wears them. I am not interested in sewing for cafe society or social climbers. I do not cater to Mary and Sue. I sew for the families of the Social Register."[17] Over the course of her career, Lowe created designs for several generations of the Auchincloss, Rockefeller, Roosevelt, Lodge, Du Pont, Post, Bouvier, Whitney, and Biddle families.[1][10][18] Lowe created dresses for many notable black clients as well, including Elizabeth Mance who was a well known pianist at the time, and Idella Kohke, a member of the Negro Actors Guild.[3]

In 1947, Janet Lee Auchincloss commissioned Lowe to create debutante gowns for her daughters Jaqueline and Caroline Lee Bouvier.[19] In 1953 she returned and hired Lowe to design a wedding dress for her daughter, the future First Lady Jacqueline Bouvier, and the dresses for her bridal attendants for her September wedding to then-Senator John F. Kennedy.[20] Auchincloss also chose Lowe to design her own wedding dress for her marriage to Hugh D. Auchincloss in 1942.[2] Lowe's dress for Bouvier consisted of fifty yards of "ivory silk taffeta with interwoven bands of tucking forming the bodice and similar tucking in large circular designs swept around the full skirt."[20] During the creation of this infamous dress, Lowe's studio flooded just 10 days before the wedding. She and her team worked tirelessly to recreate the dress. Lowe never mentioned this incident to the family and she had to pay for any additional costs.[21] The dress, which cost $500 (approximately $6,000 today), was described in detail in The New York Times's coverage of the wedding.[22][10] While the Bouvier-Kennedy wedding was a highly publicized event, Lowe did not receive public credit for her work until after the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[23]

Throughout her career, Lowe continued to work for wealthy clientele who often talked her out of charging hundreds of dollars for her designs. After paying her staff, she often failed to make a profit on her designs. Lowe later admitted that at the height of her career, she was virtually broke.[10] In 1961, she received the Couturier of the Year award[24] but in 1962, she lost her salon in New York City after failing to pay taxes. That same year, her right eye was removed due to glaucoma. While she was recuperating, an anonymous friend paid Lowe's debts that enabled her to work again. In 1963, she declared bankruptcy. Soon after, she developed a cataract in her left eye; surgery saved her eye.[9] In 1968, she opened a new store, Ann Lowe Originals, on Madison Avenue.[10] She retired in 1972.[23]

Death

editIn the last five years of her life, Lowe lived with her daughter Ruth in Queens. She died at her daughter's home on February 25, 1981, at the age of 82,[1] after an extended illness.[25] Her funeral was held at St. Mark's United Methodist Church on March 3.[10]

Legacy

editA collection of five of Ann Lowe's designs are held at the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[23][26] Three are on display at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. Several others were included in an exhibition on Black fashion at the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology in Manhattan in December 2016.[27] A children's book, Fancy Party Gowns: The Story of Ann Cole Lowe written by Deborah Blumenthal was published in 2017.[28] Author Piper Huguley wrote a historical fiction novel, By Her Own Design: a novel of Ann Lowe, Fashion Designer to the Social Register, about Lowe's life.[29][30] Her work has been admired by the designer Christian Dior, as well as the famous costumer Edith Head.[3] From September 2023 - January 2024, the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library will exhibit a collection of Ann Lowe's works from the 1920s-1960s.[19][31]

Footnotes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Fashion designer Ann Lowe Dies". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. February 28, 1981. p. 4D. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ a b (Pottker 2013, p. 135)

- ^ a b c d e Thurman, Judith (18 March 2021). "Ann Lowe's Barrier-Breaking Mid-Century Couture". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ a b (Kirkham 2002, p. 128)

- ^ a b c (Major 1966, p. 140)

- ^ a b Reed Miller, Rosemary E. (2002). Threads of time : the fabric of history : profiles of African American dressmakers, 1850-to the present. Washington, DC: Toast & Strawberries. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-9709731-0-8. OCLC 197076138.

- ^ Whitlock, Lauren. "Remembering Ann Lowe, the Black Designer Who Shaped Socialite Fashion." University Wire, Feb 25, 2021.

- ^ Alleyne, Allyssia. "The Untold Story of Ann Lowe, the Black Designer Behind Jackie Kennedy's Wedding Dress." CNN Wire Service, Dec 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Gray, Lizabeth (February 3, 1998). "Let's Talk About: Black History Month". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. pp. G–6. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Timothy M., Phelps (March 1, 1981). "Ann Lowe 82, Designed Gowns for Exclusive Clientele In Society". The New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ a b (Major 1966, p. 138)

- ^ Henderson, Marissa. “Ann Lowe: America's Overlooked Fashion Icon Finally Found.” Royal Road, vol. 3, 2019, pp. 77–90.

- ^ a b c d (Aberjhani, West & Price 2003, p. 107)

- ^ a b American Legacy, Volumes 4-5. RJR Communications. 1996. p. 38.

- ^ a b Hunt-Hurst, Patricia. "Fashion Industry." Oxford African American Studies Center. December 01, 2006. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Reed Miller, Rosemary E. (2002). Threads of time : the fabric of history : profiles of African American dressmakers, 1850-to the present. Washington, DC: Toast & Strawberries. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-9709731-0-8. OCLC 197076138.

- ^ (Major 1966, p. 137)

- ^ Terrell, Ellen. “African American Fashion Designers – from the Lincolns to the Kennedys and Beyond.” Library of Congress, 2020,

- ^ a b Way, Elizabeth (2023-09-04). "Remembering Ann Lowe, the unsung creator of Jackie Kennedy's wedding dress". Financial Times. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- ^ a b (Mulvaney 2002, p. 60)

- ^ Alleyne, Allyssia (23 December 2020). "The untold story of Ann Lowe, the Black designer behind Jackie Kennedy's wedding dress". CNN. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ (Martin Starke, Holloman & Nordquist 1990, p. 138)

- ^ a b c "Fashion designer dies at 82". Star-News. February 28, 1981. p. 3B. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ Giddings, Valerie L.; Ray, Geraldine (2010). "Trendsetting African American Designers". Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion. Bloomsbury Academic.

- ^ "Dress designer Ann Lowe". Lakeland Ledger. February 28, 1981. p. 5C. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ (Pottker 2013, p. 136)

- ^ "Why Jackie Kennedy's wedding dress designer was fashion's 'best kept secret'". New York Post. October 16, 2016.

- ^ Bush, Elizabeth (2017). "Fancy Party Gowns: The Story of Ann Cole Lowe by Deborah Blumenthal". Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books. 70 (5): 209–210. doi:10.1353/bcc.2017.0008. ISSN 1558-6766. S2CID 201782202.

- ^ "Piper Huguley". Margie Lawson. 4 July 2020. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ "Publishers Marketplace: Log In". www.publishersmarketplace.com. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ Times, The New York (2021-10-28). "Shining a Light on Forgotten Designers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

References

edit- Aberjhani; West, Sandra L.; Price, Clement Alexander (2003). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1-438-13017-1.

- Kirkham, Pat, ed. (2002). Women Designers in the USA, 1900–2000: Diversity and Difference. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09331-4.

- Major, Gerri (December 1966). "Dean Of American Designers". Ebony. 22 (2). Johnson Publishing Company. ISSN 0012-9011.

- Martin Starke, Barbara; Holloman, Lillian O.; Nordquist, Barbara K. (1990). African American Dress and Adornment: A Cultural Perspective. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. ISBN 0-840-35902-0.

- Mulvaney, Jay (2002). Kennedy Weddings: A Family Album. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-29160-4.

- Pottker, Jan (2013). Janet and Jackie: The Story of a Mother and Her Daughter, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-466-85230-3.

- Way, Elizabeth. “Elizabeth Keckly and Ann Lowe: Recovering an African American Fashion Legacy That Clothed the American Elite.” Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, vol. 19, no. 1, Feb. 2015, pp. 115–141.