Andrew Petrie (June 1798 – 20 February 1872) was a Scottish-Australian pioneer, architect and builder in Brisbane, Queensland.

Andrew Petrie | |

|---|---|

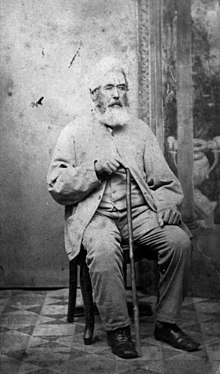

Portrait of Andrew Petrie in his later years | |

| Born | June 1798 Fife, Scotland |

| Died | 20 February 1872 Brisbane, Queensland, Australia |

| Occupation(s) | Builder, architect, public servant |

| Known for | Pioneer construction and engineering works in South East Queensland |

| Children | John Petrie, Andrew Petrie, James Rutherford Hardcastle Petrie, Walter Daniel Petrie, Thomas Petrie, Isobella Cuthbertson Ferguson (nee Petrie), William Anderson Petrie, George Barney Petrie |

Early life

editAndrew Petrie was born in June 1798 in Fife, Scotland, to parents Walter Petrie and Margaret (née Hutchinson).[1][2] He trained as a builder in Edinburgh, which is where he married Mary Cuthbertson in 1821.[2]

Career in New South Wales

editJohn Dunmore Lang brought Petrie, his wife and four sons to Sydney in 1831 with other Scottish mechanics (tradespeople) to form the nucleus of a force of free workers to construct the Australian College, which was located in Jamison Street in The Rocks.[3] Petrie along with the other mechanics, constructed the Australian College to repay the voyage from the United Kingdom funded by Lang. After construction finished, Petrie went into partnership with George Ferguson as building contractors in Sydney. This partnership lasted for two years when Petrie went into business on his own. Petrie won numerous projects and was favoured by the Government to construct many of their projects. Constructing government projects at the time, meant utilising convict labour and so their training and supervision was a key component in the construction process.

Career in Queensland

editThe quality of his work impressed his superiors so much that, when in 1837 there was an urgent appeal from the Moreton Bay Settlement of New South Wales for a competent builder to repair crumbling structures, Petrie was sent there as Superintendent of Works.[4]

Andrew Petrie and his family, the first free-settlers to move to the area, travelled to Dunwich aboard the James Watt and were then transferred in a pilot boat, manned by convicts that landed at King's Jetty, the only landing place that then existed, now known as North Quay.[4] A year after arriving in the colony Petrie and his family moved into a stone house he built at what is now known as Petrie Bight.[3]

His first important task was to repair the mechanism of the windmill which had never worked.[3] His general duty was the supervision of prisoners engaged in making such necessities as soap and nails, and in building.[2] He also made inspections of government owned sheep and cattle and placed a number of beacons on navigational hazards in the Brisbane River.[5]

Petrie's charge took him to several convict outposts and gave him a taste for travel and exploration. His private journeys soon added to knowledge of the immediate environs of the settlement. In the new surroundings he was able to pursue two main interests: as builder and architect he was responsible for most of the important structures that arose; and he made many more journeys. He was the first European to climb Mount Beerwah, one of the Glass House Mountains seen by James Cook, and he was also the first to bring back samples of the Bunya pine.[6] In 1842 with a small party in a boat he discovered the Mary River and brought back to the settlement two 'wild white men', James Davis or 'Duramboi' and David Bracewell or 'Wandi'.[2] He was the first to discover coal at Redbank in around 1837.[5] He explored and named the Maroochy River.[7]

The break-up of the Moreton Bay Penal Colony began in 1839, but it was not until 1842 that it was well advanced and that the district was declared open for settlement. During this time in 1840, Andrew founded the Petrie construction business and when the convict station was removed in 1842 Petrie saw the opportunity at last of a free community, and with his family remained to contribute to its formation and is acknowledged as the first free settler of Queensland

From 1849 to 1850 Petrie and his construction firm built Bulimba House.[8]

Later life

editIn 1848 he lost his eyesight because of inefficient surgery after an attack of sandy blight.[9] Despite this condition he still was able to design ferry landings, floating public baths and a bridge over Breakfast Creek.[3] Such was his courage that he still kept control over his business: when plans were explained to him he ordered the necessary quantities of material and was even able to check the performance of his building workers; he used his cane if not satisfied. The Petries had nine sons and a daughter. With advancing years Petrie handed over more and more control to his eldest son, John, who became first mayor of Brisbane.[5] His third son, Thomas, gained much knowledge of the Aboriginal tribes and their customs and languages. Their house was one of the social centres of Brisbane and readily offered accommodation to squatters coming from the outback, especially in the days before Brisbane had a few inns. Petrie was also always being willing to help with food and work to the poor.[2]

Andrew Petrie died on 20 February 1872 in Queensland.[2]

Legacy

editPetrie's work as an architect, stonemason and builder is reflected in a number of public buildings in Brisbane, in particular Newstead House.[10]

See also

edit- Petrie, a town in the City of Moreton Bay, just north of Brisbane

- Petrie Terrace, an inner city suburb of Brisbane

- Petrie Bight, a reach of the Brisbane River

- Petrie Bight, a former suburb of Brisbane

- Division of Petrie, an electoral district in the Australian House of Representatives, in Queensland

- John Petrie

- Thomas Petrie

- Andrew Lang Petrie, grandson

- Mount Petrie, a mountain in Brisbane

- Petrie Plaza, a prominent pedestrian mall in Canberra

- Petrie Creek, in the Sunshine Coast

- Nambour, previously known as Petrie Creek Town

- Point Arkwright, Queensland, previously known as Petrie Heads

References

edit- ^ Tonkin, Annabelle (9 April 2024). "The Petrie family". State Library Of Queensland. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Morrison, A. A. (1974). "Petrie, Andrew (1798 - 1872)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- ^ a b c d McBride, Frank; et al. (2009). Brisbane 150 Stories. Brisbane City Council Publication. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-1-876091-60-6.

- ^ a b Hadwen, Ian; Janet Hogan; Carolyn Nolan (2005). Brisbane's historic North Bank 1825 - 2005. Brisbane: Royal Historical Society of Queensland. p. 3. ISBN 0-9757615-0-1.

- ^ a b c Hacker, D. R. (1999). Petries Bight: a Slice of Brisbane History. Bowen Hills, Queensland: Queensland Women's Historical Association Inc. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-9590271-8-1.

- ^ Petrie, C. C. (1904). Tom Petrie's Reminiscences of Early Queensland. Brisbane, Queensland: Watson, Ferguson & Co. p. 11. ISBN 0-217-64617-4.

- ^ "Sunshine Coast Council, Heritage - Place names". Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ de Vries, Susanna; de Vries, Jake (2003). Historic Brisbane: Convict Settlement to River City. Frenches Forst, NSW: Tower Books. p. 31. ISBN 0-9585408-4-5. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ Dornan, Dimity; Denis Cryle (1992). The Petrie Family: Building Colonial Brisbane. Brisbane: UQ Press. p. 86. ISBN 0-7022-2346-8.

- ^ Dornan, Dimity (27 February 1992). "The Petrie Family, a Genealogical and Biographical Perspective". espace.library.uq.edu.au. Retrieved 7 November 2018.