Anaxyrus fowleri, Fowler's toad,[3] is a species of toad in the family Bufonidae. The species is native to North America, where it occurs in much of the eastern United States and parts of adjacent Canada.[1][2] It was previously considered a subspecies of Woodhouse's toad (Anaxyrus woodhousii, formerly Bufo woodhousii).[2][4]

| Fowler's toad | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Bufonidae |

| Genus: | Anaxyrus |

| Species: | A. fowleri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Anaxyrus fowleri (Hinckley, 1882)

| |

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

Etymology

editThe specific name, fowleri, is in honor of naturalist Samuel Page Fowler (1800–1888) from Massachusetts, who was a founder of the Essex County Natural History Society, which later became the Essex Institute.[5]

Description

editFowler's toad is usually brown, grey, olive green and rust red in color with darkened warty spots. If the toad has a pale stripe on its back, it is an adult. The belly is usually uniformly whitish except for one dark spot. The male may be darker in overall color than the female.

The adult toad is typically 5 to 9.5 cm (2.0 to 3.7 in) in head-body length. The tadpole is oval with a long tail and upper and lower fins, and is 1 to 1.4 cm (0.39 to 0.55 in) long.

Range

editTheir native geographic range is eastern North America. Their range extends throughout most of the southeastern and eastern United States and parts of southeastern Canada. They reside in areas near temporary or permanent wetlands as well as forested areas.

Reproduction

editFowler's toad reproduces in warmer seasons of the year, especially in May and June. It breeds in open, shallow waters such as ponds, lakeshores, and marshes. The male produces a call which attracts not only females, but also other males. The calling male may attempt to mate with one of the other males, which will then produce a chirping "release call", informing him of his mistake. It has been found that male Fowler's toads mating calls are affected by the body size and temperature of the caller. Females are often able to discriminate between variations in these calls and select the largest available males.[6] Males are able to alter their calls to make them seem more attractive to females through thermoregulation. When a male finds a female, the pair will initiate amplexus and up to 7,000 to 10,000 eggs are fertilized. They hatch in 2 to 7 days. Based on observations, Fowler's toads breed repeatedly through the spring.[7] As many as 10 different age classes, separated by several days, have been observed over the course of a breeding season in one small pond. A new tadpole may reach sexual maturity in one season, but the process may take up to three years.

Fowler's toad regularly hybridizes with two of its close relatives: the American toad and the Woodhouse's toad. The Woodhouse's toad subspecies Anaxyrus woodhousii velatus, or the East Texas toad, is possibly a hybrid of the Woodhouse's toad and the Fowler's toad.[8]

Behavior

editPredators of Fowler's toad include snakes, birds, and small mammals. It uses defensive coloration to blend into its surroundings. It also secretes a noxious compound from the warts on its back. The secretion, containing toxic bufadienolides, is distasteful to predators and can be lethal to small mammals.[9] The toad is also known to play dead.

Habitat

editFowler's toad lives in open woodlands, sand prairies, meadows, and beaches. It burrows into the ground during hot, dry periods and during the winter. They are often found hiding under broad leaved plants, amidst clumps of grass, and inside or under logs.[10] Their springtime emergence is associated with increased temperature, relatively little rainfall or wind, and a gibbous moon.[11]

Diet

editThe adult Fowler's toad eats insects and other small terrestrial invertebrates, but avoids earthworms, unlike its close relative, the American toad (Anaxyrus americanus). This toad also has been shown to eat velvet ants, which is a wasp that gives a very painful sting to humans, but does nothing to the toad.[12] The tadpole scrapes algae and bacterial mats from rocks and plants using the tooth-like structures in its mouth.

Conservation status

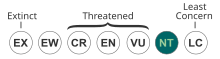

editAn important conservation measure for Fowler's toad is the protection of its breeding sites. Off-road vehicles commonly used in beach and dune habitats are damaging to this species. Agricultural chemicals have caused declines in some areas. These factors along with specific habitat requirements and excessive human activity within these habitats produces permanent, local extinctions.[13] It is considered a species at risk in Ontario,[4] a species of special concern in the U.S. state of New Jersey,[14] and a regionally threatened or endangered species in the states of New Hampshire[15] and Vermont.[16] On April 15th, 2024, Canada Post released a stamp with a Fowler's toad to raise public awareness of these amphibians. [17]

References

edit- ^ a b IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2022). "Anaxyrus fowleri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T54640A196333508. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T54640A196333508.en. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Frost, Darrel R. (2023). "Anaxyrus fowleri (Hinckley, 1882)". Amphibian Species of the World: An Online Reference. Version 6.1. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Crother, Brian I. “SSAR HERPETOLOGICAL CIRCULAR NO. 43.” Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding, Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, Topeka, KS, 2017, p. 9.

- ^ a b Fowler's Toad. Archived September 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ Dodd, C. Kenneth. (2013). Frogs of the United States and Canada. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 1,032 pp. (in two volumes). ISBN 978-1421406336.

- ^ Fairchild, Lincoln (22 May 1981). "Mate Selection and Behavioral Thermoregulation in Fowler's Toads". Science. 212 (4497): 950–951. Bibcode:1981Sci...212..950F. doi:10.1126/science.212.4497.950. PMID 17830192.

- ^ Volpe, E. Peter (September 1955). "Intensity of Reproductive Isolation between Sympatric and Allopatric Populations of Bufo americanus and Bufo fowleri". The American Naturalist. 89 (848): 303–317. doi:10.1086/281895. S2CID 85405593.

- ^ Sullivan, Brian K.; Malmos, Keith B.; Given, Mac F. (16 May 1996). "Systematics of the Bufo woodhousii Complex (Anura: Bufonidae): Advertisement Call Variation". Copeia. 1996 (2): 274–280. doi:10.2307/1446843. JSTOR 1446843.

- ^ Hutchinson, Deborah; Savitzky, Alan; Mori, Akira; Burghardt, Gordon; Meinwold, Jerrold; Schroeder, Frank (1 May 2011). "Chemical investigations of defensive steroid sequestration by the Asian snake Rhabdophis tigrinus". Chemoecology. 22 (3): 199–206. doi:10.1007/s00049-011-0078-2. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Boenke, Morgan (2012). Terrestrial habitat and ecology of Fowler's toads (Anaxyrus fowleri) (MSc thesis). McGill University. ISBN 978-0-494-84140-2. ProQuest 1034740462.

- ^ Green, Taylor; Das, Elizabeth; Green, David M. (2016). "Springtime Emergence of Overwintering Toads, Anaxyrus fowleri, in Relation to Environmental Factors". Copeia. 104 (2): 393–401. doi:10.1643/ce-15-323. S2CID 88626886.

- ^ Mergler, Ciara J.; Gall, Brian G. (2 January 2021). "Has the indestructible insect met its match? Velvet ants as prey to bufonid toads". Ethology Ecology & Evolution. 33 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1080/03949370.2020.1789747. S2CID 225392620.

- ^ Breden, Felix (1988). "Natural history and ecology of Fowler's toad, Bufo woodhousei fowleri (Amphibia: Bufonidae), in the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore". Fieldiana Zoology. New Series. 49: 1–16. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.3129.

- ^ "Wildlife Field Guide for New Jersey's Endangered and Threatened Species - Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey". www.conservewildlifenj.org. Retrieved 2021-01-10.

- ^ Department, NH Fish and Game. "Fowler's Toad | Nongame | New Hampshire Fish and Game Department". www.wildlife.state.nh.us. Retrieved 2021-01-10.

- ^ "Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-03-08.

- ^ "new canada post stamps raise awareness of endangered frogs". Canada Post. 2024-07-14.

Further reading

edit- Behler JL, King FW (1979). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 743 pp. ISBN 0-394-50824-6. (Bufo woodhousei fowleri, pp. 398–399 + Plate 248).

- Hinckley, Mary H. (1882). "On Some Differences in the Mouth Structure of Tadpoles of the Anourous Batrachians of Milton, Mass." Proc. Boston Soc. Nat. Hist. 21: 307-315 + Plate 5. (Bufo fowleri, new species). (in English and French).

- Powell R, Conant R, Collins JT (2016). Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Fourth Edition. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. xiv + 494 pp. ISBN 978-0-544-12997-9. (Anaxyrus fowleri, pp. 120–121 + Plate 8 + Figure 54 on p. 117).

- Zim HS, Smith HM (1956). Reptiles and Amphibians: A Guide to Familiar American Species: A Golden Nature Guide. Revised edition. New York: Simon and Schuster. 160 pp. (Bufo woodhousei fowleri, pp. 122–123, 157).