Anandghan was a 17th-century Śvetāmbara Jain monk, mystical poet and hymnist. Though very little is known about his life, his collection of hymns about philosophy, devotion and spirituality in vernacular languages are popular and still sung in Jain temples.

Anandghan | |

|---|---|

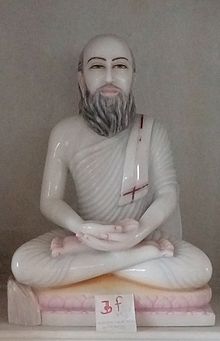

Idol in library of Lodhadham near Mumbai, Maharashtra | |

| Personal | |

| Born | Labhanand 17th century CE |

| Died | 17th century CE Possibly Medata, Rajputana |

| Religion | Jainism |

| Sect | Śvetāmbara |

| Religious career | |

| Initiation | Labhavijay |

Life

editThere is no historical information available about life of Anandghan. The majority of information is based in hagiographies and oral history.[1][2][3]

He was born in Rajputana (now Rajasthan, India). His dates differs according to sources. Generally 1603 or 1604 is accepted but he could have born before 1624 according to some estimation.[note 1][1][3] His childhood name was Labhanand. He was initiated as Jain monk and named Labhavijay.[4] He belonged to Tapa Gaccha branch of Murtipujaka Śvetāmbara Jainism and was initiated by Panyas Satyavijaya.[5] He stayed in the area of present-day north Gujarat and Rajasthan in India. Legends associate him with Mount Abu and Jodhpur. He is associated with Yashovijay also and said to have met him. He could have died in Medata in Rajasthan as a hall is dedicated to him is there. His death dates varies according to sources. Generally accepted dates are 1673 or 1674 but could have died before 1694.[note 2][1][3][6][7][8]

Works

editHis language is mix of vernacular languages like Gujarati, Rajasthani and Braj. It follows Rajasthani style of diction but is written in medieval Gujarati. It was the time when Bhakti movement was at peak and majority of devotional poets of time wrote in such vernacular languages. His works are focused bhakti (devotion) as well as internal spirituality.[1][3][6]

Anandghan Chauvisi is the philosophical treatises which supposed to contain twenty four hymns but contains twenty two. Other two hymns were later added by others. Each verse is dedicated to one of twenty four Jain tirthankaras. The legend tells that he composed these hymns in Mount Abu during his meet with Yashovijay who memorised them.[1][3][6][4][9]

Anandghan Bahattari is the anthology of hymns which differs in a number of hymns according to different manuscripts. This anthology was formed by 1775 and was transmitted orally as well as the written manuscripts. It contains pada (verses) with different ragas. Some of these verses drawn from other poets like Kabir, Surdas, Banarasidas and others.[1][3][6]

Legacy

editYashovijay, the philosopher Jain monk, was influenced by him. He wrote commentary on Chauvisi and also wrote eight verse Ashtapadi dedicated to him.[3][10][11]

His hymns are still popular in followers of Jainism as well as non-Jains because they are nonsectarian in nature and put emphasis on internal spirituality. They are sung in Jain temples. They are found in religious hymn collections especially in the collection of Digambara hymns even though he is associated with Śvetāmbara sects. A religious camp organized by Shrimad Rajchandra Mission of Rakesh Jhaveri in 2006 at Dharampur, Gujarat had lectures on Chauvisi. Mahatma Gandhi included his hymn, "One may say Rama, Rahman, Krishna or Shiva, then" in Ashram Bhajanavali, his prayer book.[3]

A Gujarati play Apoorav Khela (2012) based on his life was produced by Dhanvant Shah and directed by Manoj Shah.[12]

Further reading

edit- Imre Bangha; Richard Fynes (15 May 2013). It's a City-showman's Show!: Transcendental Songs of Anandghan. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-81-8475-985-3.

Notes and references

editNote

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f Imre Bangha; Richard Fynes (15 May 2013). It's a City-showman's Show!: Transcendental Songs of Anandghan. Penguin Books Limited. pp. x–xxxi. ISBN 978-81-8475-985-3.

- ^ Manohar Bandopadhyay (1 September 1994). Lives And Works Of Great Hindi Poets. B. R. Publ. p. 68. ISBN 978-81-7018-786-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Balbir, Nalini. "Anandghan". Institute of Jainology - Jainpedia. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ a b Behramji Malabari (1882). Gujarat and the Gujaratis: Pictures of Men and Manners Taken from Life. Asian Educational Services. p. 189. ISBN 978-81-206-0651-7.

- ^ Chidanandavijaya, Panyas. "Mahaveer Paat Parampara" (PDF). p. 235.

- ^ a b c d Amaresh Datta (1987). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: A-Devo. Sahitya Akademi. p. 163. ISBN 978-81-260-1803-1.

- ^ Ronald Stuart McGregor (1984). Hindi literature from its beginnings to the nineteenth century. Harrassowitz. p. 204. ISBN 9783447024136.

- ^ Jeṭhālāla Nārāyaṇa Trivedī (1987). Love Poems & Lyrics from Gujarati. Gurjar Grantha Ratna Karyalaya. p. 67.

- ^ John Cort (16 November 2009). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-0-19-973957-8.

- ^ Achyut Yagnik; Suchitra Sheth (2 February 2011). Ahmedabad: From Royal city to Megacity. Penguin Books Limited. p. 52. ISBN 978-81-8475-473-5.

- ^ Paul Dundas (2002). The Jains. Psychology Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-415-26606-2.

- ^ "નવું નાટક : આજે ઓપન થાય છે : અપૂરવ ખેલા". Gujarati Midday (in Gujarati). 1 April 2012. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.