Amy Maud Bock (18 May 1859 – 29 August 1943) was a Tasmanian-born New Zealand female confidence trickster. Her usual pattern involved making emotional claims to her employer or other acquaintances in order to obtain money or property, or committing some other petty scam like taking watches for "repair" and then claiming to have lost them, making purchases under her employer or acquaintance's name without permission, or claiming to sell tickets to concerts or events. She would then abscond from the area, and once caught, would immediately admit to the fraud. She often gave away the proceeds of her crimes, and pled guilty to all charges that were brought against her (except on one occasion). After thirteen periods of imprisonment totalling sixteen years and two months, her most audacious fraud involved impersonating a man named "Percy Redwood" in order to marry the daughter of a wealthy Otago family.

Amy Bock | |

|---|---|

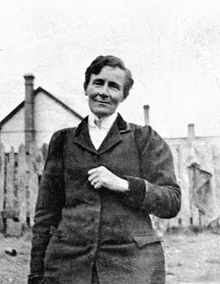

Bock, 1914 | |

| Born | 18 May 1859 Hobart, Tasmania |

| Died | 29 August 1943 (aged 84) Auckland, New Zealand |

| Resting place | Pukekohe Cemetery |

| Other names |

|

| Years active | 1884–1931 |

| Known for | Confidence trickster and male impersonator |

Both during her life and since her death, Bock has been the subject of significant media attention and interest within New Zealand. Fiona Farrell, writing in The Book of New Zealand Women (1995), described her as the country's "most unusual and energetic con-artist".[1]

Early life

editBock was born to Alfred Bock and Mary Ann Parkinson in Hobart, Tasmania, on 18 May 1859. Two or three of her four grandparents were transported convicts, with the exception of her maternal grandmother, who had travelled to Australia as a domestic servant, and the possible exception of her paternal grandfather (it being unclear whether her father's father was Alexander Cameron, a mariner, or his mother's second husband Thomas Bock, an artist and former convict).[2] Her father was an artist and photographer at the time of her birth,[3] and in 1861 he introduced the carte de visite to Australia.[4] She was the eldest of six children, only four of whom survived infancy.[5]

In 1867 the family moved from Hobart to Sale in Victoria. Her mother was in fragile mental and physical health, amongst other things suffering from a delusion that she was Lady Macbeth,[6] and was committed to a psychiatric institution in January 1872. She died in January 1875.[7][8] Historian Jenny Coleman has suggested that Bock's mother may have suffered from bipolar disorder.[9] In later years, a schoolfriend of Bock's described her as "clever and popular" at school and an accomplished pianist and horsewoman.[10] She also had a reputation as an accomplished actor from a young age, and often took on boy's roles in character plays.[11] In a statement to the Dunedin City Police Court in 1888, Bock herself said:[12]

When I was very young I remember going to a shop in the town we lived in and buying a lot of books ... without my father's knowledge, and giving them away. ... Well, when the account was sent to my father he came to me and told me never to get anything without first receiving an order from him. He told me that anything I needed I must go to him for, and I should have it; but his saying that only seemed to increase the desire to get things without his knowing. I did so many times, and at last, when his patience was worn out, he took me into his room and told me of my mother's fate, and said he feared I showed the same symptoms.

Teaching in Victoria

editIn 1876, at the age of around 17, Bock was sent to boarding school in Melbourne, where she stayed for nearly two years. Her family's financial situation was poor and she took up schoolteaching in order to contribute to the family income.[13] Her father helped her obtain a position as the only teacher at a rural school.[9] For the next decade of her life, Amy Bock worked as a teacher in Gippsland. She was regularly absent, claiming illness, and on at least two occasions was found by inspectors to have falsified the school attendance rolls in order to make it appear that more children were in attendance, thereby inflating her salary.[14] She also incurred extensive debts in Melbourne, using her status as a teacher to obtain credit.[15] In attempting to avoid her obligations, she wrote a number of letters to creditors pleading for more time to pay her debts, including two letters purporting to be from her sister Ethel reporting that Amy had died.[16]

In May 1884 Bock was arrested and charged with obtaining goods by false pretences.[16] The Age in its editorial wrote that her salary of £9 per month was "found not nearly sufficient to cover her rather extravagant habits", and noted that it was argued she was not responsible for her conduct because "insanity exists in her family on the side of the mother, who died many years ago in a Tasmanian lunatic asylum".[17] A local newspaper, The Gippsland Times, reported that Bock was "always strange in her manner, from earliest childhood, and most impatient of restraint, indeed at times quite uncontrollable".[18] On the basis of her ill-health and lack of responsibility for her actions, she was discharged without conviction, and bound on a pledge of good behaviour for twelve months.[19] Her father subsequently persuaded her to emigrate to New Zealand, where he lived in Auckland with his second wife (who was only a year older than Bock).[8][20]

Move to New Zealand

editSoon after moving to New Zealand, and having found it difficult to live in the family home with her new stepmother, Bock found work as a governess in Ōtāhuhu.[21] This position was to prove short-lived. After a few weeks of employment, her first court appearance took place in May 1885, before the Auckland Police Court, on the charge of obtaining one pound and concert tickets by false representations. The court decided that she was not responsible for her actions and she was discharged into the care of a local storekeeper.[8][22]

Bock subsequently moved to Lyttelton, where she entered service as a governess to family friends from Victoria who now ran a hotel.[22] Eight months into her new employment, she informed her employers that she had inherited a large sum of money; when this story was disbelieved, she took offence and resigned. She subsequently obtained goods on credit again and travelled to Wellington, but was apprehended and brought back to Christchurch before the Resident Magistrate's Court in April 1886.[23] She was convicted and sentenced to one month's hard labour and imprisonment at Addington Prison.[8] This was Bock's first experience in prison, and on her release she moved to Wellington, where she in short order resumed obtaining goods by false pretences. She also obtained employment as a matron at the Otaki Maori Boys' College, where she used some of her ill-gotten funds to purchase boots for her pupils.[24]

In July 1887, she appeared again before the court on fraud charges, and was sentenced to six months' detention at Caversham Industrial School in Dunedin.[8][25] The governor of the prison was impressed by her manners and social skills and offered her a position as a teacher. However, he then found her to be engineering her escape through correspondence with a supportive but fictitious aunt.[26] She was discharged in January 1888 and took up independent music instruction, only to fall afoul of the law once again and appear back in court in April 1888 for her habitual offence of receiving goods under false pretences. She was sentenced to another two months' imprisonment,[8] despite requesting that she be admitted to a lunatic asylum and claiming that she had inherited madness and kleptomania from her mother.[27][28] The judge hearing the case commented that kleptomania was "only another name for stealing".[12]

In 1889, Bock moved to Akaroa, on Banks Peninsula. She again found work as a governess, but reoffended and was brought before the Christchurch Magistrate's Court again. The prosecutor pointed out Bock's lengthy record to the court, and she was sentenced to concurrent six-month sentences for larceny and false pretences in April 1889.[8][29] After serving her full sentence, she returned to Dunedin, where she worked as a housekeeper. In April 1890 she sought to pawn her employer's assets, and absconded from Dunedin in early May. She was arrested in Geraldine on 17 May 1890.[30] Bock was unrepresented in court and did not deny charges of obtaining money by false pretences and forging a promissory note.[31] The prosecutor described the fraud as "the most cunning scheme that had ever been adopted in the colony".[32] On the basis of her previous record, the court sentenced her to the maximum sentence of three years' penal servitude.[33]

Further criminal career

editAfter serving two years and four months of her sentence, with time off for good behaviour, Bock resettled in Timaru in October 1892.[33] She almost immediately presented herself as a wealthy tourist and obtained a loan of £1 from a local school principal, claiming to have lost her pocketbook.[34] After disappearing with the money, she was quickly caught and sentenced to a term of one month's imprisonment. She claimed that she had been disturbed by news of her father's death, but he was in fact still alive and had moved to Melbourne.[35] After her release, she first made contact with local branch of the Salvation Army, and committed several further thefts, including pawning her landlady's husband's watch in April 1893, which led to a six months' prison sentence.[36]

On her release in October 1893, she moved to Oamaru at the invitation of a Salvation Army friend, where she sought to purchase a six-roomed house and section in repayment for her friend's kindness, claiming to have received a substantial inheritance.[37] She also borrowed various sums of money from a furniture seller, after having advised him that she would be spending £75 on furnishings for the house.[38] She now applied for formal membership into the Salvation Army, but the local captain was aware of her history and said he would await proof that she had changed her lifestyle. After defrauding Salvation Army members out of thirty shillings for tickets to an event, she left Oamaru and headed to Palmerston. She was swiftly apprehended,[39] and in January 1894 imprisoned again for four months with hard labour (her eighth prison sentence since 1886).[40] In October 1895 she was imprisoned again for three months for not paying her board and lodging.[8][41]

On release, Bock was sent to the Catholic-run Mount Magdala Home in Christchurch. This institution had been set up for "fallen" women and there are no records of her time there.[41] In 1901, she began working as a housekeeper in Waimate under the name of Miss Sherwin, later leaving town and faking the death of Miss Sherwin in order to avoid the large debts she had accumulated.[42] In 1902, masquerading as Miss Mary Shannon in Christchurch, she befriended Alfred William Buxton, a well-known landscape gardener and nurseryman, and became a guest at his home.[43] Through him she met and defrauded investors of sums required to start a fictitious poultry farm in Mount Roskill, and was again imprisoned for two years with hard labour in March 1903.[8][44] She had developed a reputation with the police by this stage as being curiously moral, in that she was known for giving away her ill-gotten gains, particularly to young female servants.[45] At this time The Evening Post published a lengthy article about her, headlined "Remarkable Female Swindler: Unique in Colonial Criminology", claiming that "this woman stands supreme in cleverness over other female criminals, and in her own particular line her position is probably unique".[46]

Bock earned a reduction in her sentence for good behaviour, and was freed in October 1904. She was admitted to the Samaritan Home in Christchurch but left within two days.[47] She found work at Rakaia as "Amy Chanel", but was charged in February 1905 with attempting to alter a cheque.[8] Uncharacteristically, she denied committing this crime and pled not guilty, but was convicted by the jury and received a three-year sentence.[48] She served two-and-a-half years, and was released in 1907, whereupon she took up residence at the Samaritan Home.[49] She befriended members of the Pollard's Lilliputian Opera Company at this time who were performing at the Theatre Royal, travelled with them to Dunedin, and committed a number of small frauds in order to present herself as a patron of the company.[50]

In 1908, she became a housekeeper in Dunedin under the assumed name of Agnes Vallance, where she was a popular addition to the family. At Christmas she was left in charge of the house and set out to obtain loans using the household furniture as collateral and under the assumed name of Charlotte Skevington.[51] A warrant was issued for her arrest in January 1909 but by this point Bock had disappeared.[52][8]

"Percy Redwood" affair

editPurported marriage

editIn January 1909, under the invented name of "Percival Leonard Carol Redwood", and posing as an affluent Canterbury sheep farmer, Bock became a popular guest at a respectable boarding house in Dunedin. A fellow guest would later comment that "Percy" seemed to be "the essence of all that was good and kind. ... His affable and obliging nature made us all like him."[53] After several weeks, Bock travelled to Port Molyneux on the South Otago coast. Here, under cover of her male identity, she wooed Agnes Ottaway (known as Nessie to her family), the daughter of the landlady of Albion House, a large private guesthouse popular with tourists.[54] Bock maintained her male impersonation through adept use of letters purported to be from lawyers and from Redwood's family, postal orders and small loans.[55][8]

"Percy" and Ottaway married on 21 April 1909, at an elaborate ceremony attended by 200 guests and the local MP.[1] At the last moment Redwood's purported family members wrote to say that they would not be able to attend the ceremony.[56] Suspicions were raised by their absence and by Redwood's failure to pay debts leading up to the wedding.[57][58] The morning after the wedding, the bride's parents and a number of close family friends confronted Redwood about his finances and gave him a week's grace to pay his debts, on the basis that there would be no honeymoon until he had done so. Two of the family friends subsequently made further enquiries and found they were unable to trace the existence of Redwood's mother; they reported their concerns to the police.[59] A local detective recognised the tell-tale signs of Bock's fraudulent activity, and showed them a photo of her; she was immediately identified.[60]

Arrest and annulment

editThree days after the wedding, Bock was arrested at the Ottaways' guesthouse; the Ottaway family were shocked and surprised, although the bride's father was said to have commented, "Well, it might have been worse."[61][8] Bock was then taken back to the Dunedin Supreme Court. The Evening Star described her entrance into the court, stating: "A front view showed a diminutive man, well dressed, neat of limb, with neater feet, and rather good-looking ... A back view made it almost impossible to believe that the little man between the detectives was a woman."[62] Newspapers in both Australia and New Zealand reported extensively on the events;[63] the New Zealand Herald said the situation was "more like a romance than anything else".[64]

Bock pled guilty to all charges against her. She was convicted of obtaining by false pretences (including in relation to her Christmas thefts as Agnes Vallance) and making a false declaration under the Marriage Act, and sentenced to two years' imprisonment with hard labour.[65] She was also declared a "habitual criminal",[8] which meant that she would be detained in prison "till such a time as the Governor is convinced that she can be granted her liberty with perfect safety to the public" (an early form of preventative detention).[66] She was only the second woman in New Zealand to have been declared a habitual criminal.[67] In a summary of her previous convictions and sentences given to the court, the prosecutor noted that she had been convicted on thirteen occasions and subject to prison sentences totalling sixteen years and two months, with the duration of her sentences ranging from one month to three years.[68]

Agnes Ottaway subsequently petitioned the Supreme Court for the annulment of the marriage, which Bock did not oppose. At the hearing, her counsel noted that it was clear that the marriage was not binding in the circumstances but that it would be desirable to have this legally recorded. He noted that a similar case had come before the Supreme Court in Dunedin eight years previously, with the difference being that in that case the two women had lived together for eight years before they parted. Ottaway was described as looking "pale and worried" in the witness box, and said that at the time of the ceremony she had "no reason to believe that [Bock] was not a man". The petition was granted.[69] In April 1910, it was reported that Ottaway had married a stock inspector and widower some twenty years' her senior. After his death in September 1918, in 1927 she married a soldier she had known since childhood. She died in 1936.[70]

Public reaction

editThe events of Bock's marriage quickly became notorious. Robert William Robson, a journalist who worked for the Otago Daily Times, wrote a four-part serialised pamphlet that was published widely, and newspapers saw unprecedented demand for editions covering the story.[71] Items from the wedding were auctioned off at an event on 17 May 1909, with the Otago Daily Times describing the auction rooms as "packed to suffocation" with spectators.[72] Joseph Ward, then the prime minister, compared another politician's false statements to Bock's marital promises.[73] Postcards were sold by local entrepreneurs,[74] and a number of newspapers published poems about the events.[75][76][77][78] In 1910, a wharf worker brought a private prosecution in the Magistrate's Court against another wharf worker, saying the latter had persistently insulted him by calling him "Amy Bock". The defendant wharf worker was convicted of using insulting words and fined 20 shillings with costs.[79][80]

Later life

editBock's behaviour in prison was exemplary, and she was released on probation in early February 1912 notwithstanding her "habitual criminal" status.[81] Upon her release, Amy Bock worked at a New Plymouth retirement home and subsequently as a housemaid in the small town of Mokau.[82] She also assisted the teachers of the local schools and became a popular member of the community.[83] She married Charles Christofferson, a Swedish immigrant and ferryman, in November 1914.[84] As a result of her marriage, she was granted an unconditional discharge from her probation in 1915.[85] However, due to Bock's indebtedness, the marriage foundered within that year.[8]

In March 1917, Bock appeared before the New Plymouth Magistrates Court on further fraud charges. She admitted having obtained fifteen pounds from a local flax mill manager for the purchase of a piano on false pretences.[86] Her barrister successfully argued that a fine should be imposed instead of a prison sentence, in view of her good character since her previous release from prison, and she was fined ten pounds plus court costs.[87] She lived quietly in Mokau for a few years after, known locally for her talents as a musician.[88] In around 1925 she moved to Hamilton where she may have worked for a time as a cook in a Salvation Army home.[89] It was not until 1931, fourteen years after her previous court appearance and at the age of 71, that she appeared again on five charges of obtaining money by false pretences.[8] She was described in newspaper reports as "a faded old lady in a dove grey alpaca cloth costume with a drooping hat of lace straw, grey gloves".[90] As usual, she pled guilty on all charges. Although estranged from her husband, she was still using the name Christofferson at this time.[91]

Bock was given a two-year probationary sentence in October 1931, conditional on her residence at a Salvation Army home supervised by Annie Gordon.[92] There are no records of her time there and it is not known where or how she spent the final years of her life.[93] Bock died in Auckland on 29 August 1943 and was buried in an unmarked grave in Pukekohe Public Cemetery.[8][93]

Legacy

editSome modern commentators have suggested that Bock may have been an early feminist, or that the "Percy Redwood" masquerade indicated that she was attracted to women.[94][95][96] In support of the latter theory, there is evidence that she often gave the proceeds of her frauds to servant girls or female friends. On the other hand, Agnes Ottway quickly had the marriage annulled when she found out her "husband's" actual gender, and there is no other evidence of Bock having romantic relationships with women.[97] It is unclear what Bock's long-term plan was, but historians think it was unlikely that she was planning to remain with Ottaway; she may have been planning to abscond shortly after the wedding with jewellery and other items obtained on credit.[96][58] Any potential homosexual connotations were largely ignored by newspapers at the time; the media instead treated the idea of a marriage between two women as absurd or humorous.[98]

Fiona Farrell wrote a play in 1982 about Bock called In Confidence: Dialogues with Amy Bock. It was written for the Women's Studies Association conference that year, and premiered at the BATS Theatre in Wellington.[99][100][101] In 1997 New Zealand playwright Julie McKee, then a recent drama school graduate, wrote a play called The Adventures of Amy Bock, which was professionally staged at Yale Repertory Theatre.[102][103] A review for Variety was critical of the play, saying McKee "does not make Bock's adventures as involving as they could be".[104]

In 2009, to mark the centenary of the Redwood-Ottaway marriage, South Otago Museum organised various events including a re-enactment of the wedding with the audience encouraged to wear period costume, an afternoon tea and a brass band concert. More than 300 people attended the re-enactment. Her great-niece, textile artist Lynne Johnson, and New Zealand artist Fiona Clark also hosted a multimedia art exhibition with works relating to Bock and her life at the South Otago Creative Arts Centre.[105][106] Clark's grandfather had met Bock while she was living in Mokau, and Clark has said that she has been fascinated by Bock's story since she was 14.[107]

In 2010, historian Jenny Coleman published a comprehensive biography of Bock.[108]

Notes

edit- ^ a b Farrell 1995.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 17–33.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 36.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 47–49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Farrell, Fiona. "Bock, Amy Maud". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ a b Ray, William (12 November 2018). "Con-artist: the story of Amy Bock". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ "Amy Bock: Amy Bock's Childhood". Wanganui Herald. 11 May 1909. p. 2. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 46.

- ^ a b "Alleged Kleptomania". Otago Daily Times. No. 8155. 12 April 1888. p. 4. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 58–93.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 117.

- ^ a b Coleman 2010, p. 118.

- ^ "News of the Day". The Age. 26 May 1884. p. 5. Retrieved 26 May 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 120.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 129.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 130.

- ^ a b Coleman 2010, p. 131.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 132.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 139.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 150.

- ^ "Sentence on Amy Bock". Evening Post. 11 April 1888. p. 2. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 156.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 157–160.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 161.

- ^ "An Artful Schemer". Otago Witness. No. 1895. 29 May 1890. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ a b Coleman 2010, p. 164.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 165.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 167–169.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 170.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 171.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 172.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 174–175.

- ^ a b Coleman 2010, p. 177.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 178–179.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 180.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 181.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 184.

- ^ "Remarkable Female Swindler: Unique in Colonial Criminology". The Evening Post. 17 March 1903. p. 5. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 190.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 191.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 192.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 199.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 202.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 206–210.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 229.

- ^ a b Yarwood, Vaughan (June 2019). "The Case of the Female Bridegroom". New Zealand Geographic. No. 157. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 236.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 237.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 238.

- ^ "Amy Bock's Latest Escapade: Masquerades in Men's Clothing". The Evening Star. No. 14043. 26 April 1909. p. 4. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 242–247.

- ^ "In Man's Clothing. A Masquerading Woman Marries Another Woman: An Extraordinary Story". New Zealand Herald. Press Association. 27 April 1909. p. 5. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 256.

- ^ "Amy Bock". Greymouth Evening Star. 31 May 1909. p. 2. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 276.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 274.

- ^ "Amy Bock: "Mrs Redwood" Free Again!". NZ Truth. No. 209. 26 June 1909. p. 5. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 289–290.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 281–283.

- ^ "A Sensation's Aftermath". Otago Daily Times. No. 14526. 18 May 1909. p. 6. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 249.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 257.

- ^ "The Irrepressible Amy Bock". The Observer. 15 May 1909. p. 23. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Johnston, J.G. (10 May 1909). "The Triumphs of Amy Bock". Hawera & Normanby Star. p. 7. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Amy Bock, the Masquerader". Waikato Independent. 29 May 1909. p. 6. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "In Brief". New Zealand Times. 15 May 1909. p. 13. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Insulting Words: A Peculiar Court Case". Evening Post. 14 March 1910. p. 7. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ ""Hello, Amy!": Miss Bock Revived. Wharf Workers' Wordy Warfare". NZ Truth. 19 March 1910. p. 8. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 291.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 300.

- ^ Coleman 2010, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 304.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 303.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 308.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 315.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 317.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 319.

- ^ "Links with the Past: Amy Bock Before the Court". Wairarapa Daily Times. 8 October 1931. p. 5. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 321.

- ^ a b Coleman 2010, p. 323.

- ^ Keogh, Brittany (10 March 2018). "NZ Police Gazettes records from 1878 to 1945 published on Ancestry.com.au". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 336.

- ^ a b Mary 1995, p. 20.

- ^ Coleman 2010, p. 337.

- ^ Mary 1995, p. 21.

- ^ "Eva Radich: Career Highlights". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "In Confidence: Dialogues with Amy Bock". Playmarket. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "Playscripts". National Library of New Zealand. January 1982. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Klein, Alvin (6 April 1997). "Making Artistry of the Con". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Malcolm (4 April 1997). "'Adventures of Amy Bock': Bumpy But Absorbing Theatre at Yale Rep". Hartford Courant. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Markland (13 April 1997). "The Adventures of Amy Bock". Variety. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Conway, Glenn (7 February 2009). "1909 sex scandal to be re-enacted". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Conway, Glenn (13 April 2009). "Notorious 'groom' takes vow". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Clark, Fiona (21 February 2020). "'I am who I am': Photographer Fiona Clark on Auckland queer culture in the 70s". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Coleman 2010.

References

edit- Coleman, Jenny (2010). Mad or Bad? The Life and Exploits of Amy Bock. Dunedin: Otago University Press. ISBN 978-0-947522-18-6.

- Farrell, Fiona (1995). "Amy Bock". The Book of New Zealand Women: Ko Kui Ma Te Kaupapa (4th ed.). Wellington, NZ: Bridget Williams Books Ltd. pp. 90–93. ISBN 0-908912-04-8.

- Mary, Johanna (1995). "Amy Bock and the Western Tradition of Passing Women". New Zealand Studies. 5 (3). Retrieved 31 May 2021.

External links

edit- "Con-artist: the story of Amy Bock", podcast and article on Radio New Zealand

- "The Notorious Amy Bock, 1909" in An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand (1996), edited by A. H. McLintock