The American golden plover (Pluvialis dominica) is a medium-sized plover. The genus name is Latin and means relating to rain, from pluvia, "rain". It was believed that golden plovers flocked when rain was imminent. The species name dominica refers to Santo Domingo, now Hispaniola, in the West Indies.[2]

| American golden plover | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult summer plumage, Churchill, Manitoba | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Charadriidae |

| Genus: | Pluvialis |

| Species: | P. dominica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pluvialis dominica (Müller, PLS, 1776)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pluvialis dominica dominica | |

Description

editMeasurements:[3]

- Length: 24–28 cm (9+1⁄2–11 in)

- Weight: 122–194 g (4+5⁄16–6+13⁄16 oz)

- Wingspan: 65–67 cm (25+1⁄2–26+1⁄2 in)

The breeding adult American golden plover has a black face, neck, breast, and belly, with a white crown and nape that extends to the side of the breast. The back is mottled black and white with pale, gold spots. The breeding female is similar, but with less black. When in winter plumage, both sexes have grey-brown upperparts, pale grey-brown underparts, and a whitish eyebrow. The head is small, along with the bill.[4]

It is similar to two other golden plovers, European and Pacific. The American golden plover is smaller, slimmer and relatively longer-legged than European golden plover (Pluvialis apricaria) which also has white axillary (armpit) feathers. It is more similar to Pacific golden plover (Pluvialis fulva) with which it shares grey axillary feathers; it was once considered conspecific under the name "lesser golden plover".[5] The Pacific golden plover is slimmer than the American species, has a shorter primary projection, and longer legs, and is usually yellower on the back. In breeding plumage, the American golden plover has a solid black lower belly and undertail, while the Pacific and European golden plovers have at least some to extensive white on the flanks and undertail. However, first-summer immature birds often gain only partial summer plumage with incomplete black and can be confused more easily. Another useful distinction is that in fall, the post-breeding moult is a month or more later in American golden plover (September to October, on the wintering grounds) than in Pacific golden plover (August).[6][7]

Distribution

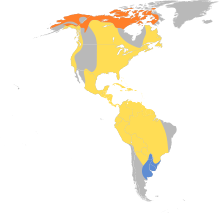

editThe breeding habitat of American golden plover is Arctic tundra in northern Canada (Baffin Island west to Yukon and northernmost British Columbia) and Alaska. They nest on the ground in a dry open area. They are migratory and winter in southern South America. They follow an elliptical migration path; northbound birds pass through Central America from January to April[8][9] and stage in great numbers in places like Illinois before their final push north. In fall, they take a more easterly route, flying mostly over the western Atlantic and Caribbean Sea to the wintering grounds in Patagonia. The bird has one of the longest known migratory routes of over 40,000 km (25,000 mi). Of this, 3,900 km (2,400 mi) is over open ocean where it cannot stop to feed or drink. It does this from body fat stores that it stocks up on prior to the flight.

It is a regular though scarce fall migrant in western Europe, with typically 20–25 sightings annually in Great Britain; spring records are much rarer.[10]

A comparison of dates and migratory patterns leads to the conclusion that Eskimo curlews and American golden plovers were the most likely shore birds to have attracted the attention of Christopher Columbus to the nearby Americas in early October 1492, after 65 days at sea out of sight of land.[11]

Behaviour

editBreeding

editThis bird uses scrape nests, lining them with lichens, grass, and leaves. At its breeding grounds, it is very territorial, displaying aggressively to neighbours. Some American golden plovers are also territorial in their wintering grounds.[12]

The American golden plover lays a clutch of four white to buff eggs that are heavily blotched with both black and brown spots. The eggs generally measure around 48 by 33 mm (1+7⁄8 by 1+5⁄16 in). These eggs are incubated for a period of 26 to 27 days, with the male incubating during the day and the female during the night. The chicks are precocial on hatching, leaving the nest within hours and feeding themselves within a day.[12]

Diet

editThese birds forage for food on tundra, fields, beaches and tidal flats, usually by sight. They eat terrestrial earthworms, terrestrial snails,[13] insects, insect larvae,[13] crustaceans,[4] fish, berries and seeds.[13]

Status

editLarge numbers were shot in the late 19th century and the population has never fully recovered.

Gallery

edit-

Feigning injury to protect its chicks, showing its mottled black-and-gold back; August, Alaska.

-

Fresh juvenile on fall migration, September, Toronto.

-

First-summer birds on spring migration can get very worn and dull, without the usual mottled plumage; April, Creve Coeur, Missouri.

-

Scrape nest with four eggs; Nome, Alaska.

References

edit- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Pluvialis dominica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22693740A93420396. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22693740A93420396.en. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 138, 311. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "American Golden-Plover Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- ^ a b Vanner, Michael (2004). The Encyclopedia of North American Birds. Bath, England: Parragon. pp. 123. ISBN 0-75258-734-X.

- ^ Reviewed in Sangster, George; Knox, Alan G.; Helbig, Andreas J.; Parkin, David T. (2002). "Taxonomic recommendations for European birds". Ibis. 144 (1): 153–159. doi:10.1046/j.0019-1019.2001.00026.x.

- ^ Hayman, Peter; Marchant, John; Prater, Tony (1986). Shorebirds. Breckenham, UK: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-7099-2034-2.

- ^ Svensson, L., Mullarney, K., & Zetterström, D. (2009) Collins Bird Guide, ed. 2. ISBN 0-00-219728-6, pages 148-149.

- ^ Strewe, Ralf; Navarro, Cristobal (2004). "New and noteworthy records of birds from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region, north-eastern Colombia". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 124 (1): 38–51.

- ^ Herrera, Néstor; Rivera, Roberto; Ibarra Portillo, Ricardo; Rodríguez, Wilfredo (2006). "Nuevos registros para la avifauna de El Salvador" [New records for the avifauna of El Salvador] (PDF). Boletín de la Sociedad Antioqueña de Ornitología (in Spanish and English). 16 (2): 1–19.

- ^ White, Steve; Kehoe, Chris (July 2024). "Report on scarce migrant birds in Britain in 2022". British Birds. 117 (7): 365.

- ^ Gollop, J.B.; Barry, T.W.; Iversen, E.H. (1986). "Eskimo Curlew - A vanishing species? : The Eskimo Curlew's Year - Introduction to Oceanic Migration". Nature Saskatchewan & United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 29 November 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ a b Hauber, Mark E. (1 August 2014). The Book of Eggs: A Life-Size Guide to the Eggs of Six Hundred of the World's Bird Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-226-05781-1.

- ^ a b c "Pluvialis dominica (American golden plover)". Animal Diversity Web.

External links

edit- American golden plover at ENature.com

- BirdLife species factsheet for Pluvialis dominica

- "Pluvialis dominica". Avibase.

- "American golden plover media". Internet Bird Collection.

- American golden plover photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- American Golden Plover species account at Neotropical Birds (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

- Interactive range map of Pluvialis dominica at IUCN Red List maps

- Audio recordings of American golden plover on Xeno-canto.

- Pluvialis dominica in Field Guide: Birds of the World on Flickr

- american-golden-plover/pluvialis-dominica American golden plover media from ARKive