Alotenango (Alo-tenamitl-co; translation "in the wall of the parrots")[2] (variation: Atchalan)[3] is a town and municipality in the Guatemalan department of Sacatepéquez. According to the 2018 census, the town has a population of 23,358.[4] The municipality consists of four wards and is situated on the Escuintla road (National Highway 14).[5] Located in a valley, Alotenango is a Ladino coffee center, since the times of general Justo Rufino Barrios liberal regime (1873–1885).[6]

Alotenango | |

|---|---|

Municipality and town | |

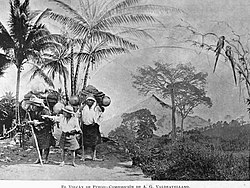

Photographic composition of Volcán de Fuego as seen from Alotenango in 1897. Composition by Alberto G. Valdeavellano. | |

| Coordinates: 14°29′16″N 90°48′21″W / 14.48778°N 90.80583°W | |

| Country | |

| Department | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 98.7 km2 (38.1 sq mi) |

| Population (2018 census)[1] | |

| • Total | 23,986 |

| • Density | 240/km2 (630/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central Time) |

| Climate | Cwb |

History

editAccording to the Popol Vuh, the town is mentioned as Vucuc Caquix. The community of Alotenango grew up originally 3 to 4 kilometers south of the current settlement which today is the Candelaria farm. This settlement was established before the Spanish arrived in Alotenango in 1524.[8] In the 1540s, bishop Francisco Marroquín split the religious coverage of the Guatemala central valley between the Order of Preachers and the Franciscans, getting to the latter the Alotenango curato, among others.[9] Given that there was not a separation of Church and State, the curato division was transferred into the geography of the valley; thus, the Alotenango valley was delimited by the Guatemala valley – that is, Antigua Guatemala to the east, Chimaltenango valley to the north, and the Escuintla Province to the south and west.[10]

In 1881, French writer Eugenio Dussaussay climbed the volcano, then practically unexplored.[11] First, he needed to ask for permission to climb to Sacatepéquez governor, who gave him a letter for Alotenango major asking him for guides to help the explorer and his companion, Tadeo Trabanino.[12] They wanted to climb the central peak, unexplored at the time, but could not find a guide and had to climb to the active cone, which had had a recent eruption in 1880.[13] His guide, Rudecindo Zul, from Alotenango, was the only one to offer to help, but only to the saddle that divides Fuego from volcán Acatenango, as the townspeople feared and respected the mountain too much to go beyond that point.[13]

Archeologist Alfred Percival Maudslay, in his book A Glimpse at Guatemala, tells about his expeditions to volcán de Fuego. The second one took place on 1 January 1892, from Alotenango,[14] and he described it as follows:[15]

"On New Year's day, 1892, I climbed up Agua again, and as it was fortunately a clear day I took a round of angles and some photographs. During the next few days I made the acquaintance of Dr. Otto Stoll, who was then practicing medicine in Antigua, and collecting the valuable notes on the Indian languages which he has since published, and, to my great delight, I learnt that he wished to make the ascent of Fuego; so we arranged to start the very next day for the village of Alotenango. On 7 January we left that village about 7 o'clock in the morning with seven Mozos, carrying food, clothing, and my camp-bed, and rode for an hour towards the mountains, when we dismounted and sent back our mules. The first two hours' climb was not so very steep, but it was tiring work walking over the loose mould and dry leaves under the thick forest."

Culture

editThe municipality is home to a Franciscan monastery and a large church. A large hut has been used as a courthouse; the sandy plaza holds a Sunday market.[3]

The residents, mainly Maya peoples, are notable for a highly particular local culture retaining elements from their ancient Maya society past while including elements from the dominant Hispanic culture as well.[16] Most of the people are peasant Cakchiquel who once spoke only Cakchiquel but now mainly speak Spanish.[17] Other historians believe the town is inhabited by descendants of Nahua speaking Pipils, an indigenous people who live in western El Salvador.[5] However, in the Titulo de Alotenango, a 16th-century legal document, the land dispute claims were between the Cakchiquel of Alotenango and the Pipil of Escuintla.[18]

Married couples leave their patrilocal extended household only after several children are born.[17] 24 June is a festival day in honor of Saint John the Baptist, the town's patron saint.

Economy

editUnder Anacafé, Alotenango is situated in the Antigua coffee region.[19]

The Capetillo farm was developed in the 18th century by Spanish Royal Treasurer Juan Antonio Capetillo. Formed from different lots totaling seven caballertas, it only grew sugar cane until 1875. The farm was purchased by Jose Mariano Rodriguez in 1875, and he began coffee cultivation. Revenue generation figures for that year were 2,800 pesos, increasing to 12,000 pesos in 1878. In 1880, there were 200,000 producing coffee trees, a mill, and 25,000 pesos of revenue. Capetillo coffee was awarded the only Grand Prize for Coffee at the 1915 Universal Exhibition.[20]

Climate

editAlotenango has a temperate climate (Köppen climate classification Cwb).

| Climate data for Alotenango | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 23.8 (74.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.4 (74.1) |

24.7 (76.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.0 (64.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

14.8 (58.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

14.3 (57.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 5 (0.2) |

9 (0.4) |

16 (0.6) |

41 (1.6) |

168 (6.6) |

389 (15.3) |

275 (10.8) |

288 (11.3) |

420 (16.5) |

218 (8.6) |

35 (1.4) |

10 (0.4) |

1,874 (73.7) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[21] | |||||||||||||

Geographic location

editThe town is the starting point for the ascent of Volcán de Agua which like most other places within the department looms above to the immediate east of the town. There is also a direct ascent available for Volcán de Fuego from Alotenango.[22] National Highway 14 connects Alotenango to the cities of Antigua Guatemala in the north and Escuintla in the south.

See also

editNotes and references

editReferences

edit- ^ Citypopulation.de Population of departments and municipalities in Guatemala

- ^ Membreño, Alberto (1901). "Nombres Geograficos de Guatemala". Nombres geográficos indígenas de la república de Honduras. Tipografía Nacional. p. xix.

- ^ a b Moore 1998, pp. 415–416

- ^ Citypopulation.de Population of cities & towns in Guatemala

- ^ a b Faubert & Soldevila 2000, p. 142

- ^ Stewart & Whatmore 2002, pp. 112, 114.

- ^ Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, p. 39.

- ^ "Alontenango:Historia" (in Spanish). Inforpressca. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Juarros 1818, p. 336.

- ^ Juarros 1818, p. 345.

- ^ Dussaussay 1897, p. 180.

- ^ Dussaussay 1897, p. 179-182.

- ^ a b Dussaussay 1897, p. 179.

- ^ Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, p. 38.

- ^ Moore 1998, p. 426

- ^ a b Moore 1998, p. 311

- ^ Williams 2002, p. 334

- ^ "Antigua Coffee". antiguacoffee.org. Archived from the original on 11 December 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Wagner & Von Rothkirch 2001, pp. 114, 135.

- ^ "Climate: Alotenango". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ Stewart & Whatmore 2002, p. 115

- ^ a b SEGEPLAN. "Municipios de Sacatepéquez, Guatemala". Secretaría de Planificación y Programación de la Presidencia. Guatemala. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

Bibliography

edit- Dussaussay, Eugenio (1897). "Impresiones de viaje: el volcán de Fuego". La Ilustración Guatemalteca (in Spanish). I (12). Guatemala: Síguere, Guirola & Cía.

- Faubert, Denis; Soldevila, Carlos (2000). Guatemala. Hunter Publishing, Inc. ISBN 2-89464-175-3.

- Juarros, Domingo (1818). Compendio de la historia de la Ciudad de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Ignacio Beteta.

- Maudslay, Alfred Percival; Maudslay, Anne Cary (1899). A glimpse at Guatemala, and some notes on the ancient monuments of Central America (PDF). London, UK: John Murray.

- Moore, Alexander (1998). Cultural Anthropology: The Field Study of Human Beings. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 415–416. ISBN 0-939693-48-8.

- Stewart, Iain; Whatmore, Mark (2002). The Rough Guide to Guatemala. Rough Guides. p. 115. ISBN 1-85828-848-7.

- Wagner, Regina; Von Rothkirch, Cristóbal (2001). The history of coffee in Guatemala. Villegas Asociados. pp. 114, 135. ISBN 958-8156-01-7.

- Williams, Gareth (2002). The other side of the popular: neoliberalism and subalternity in Latin America. Duke University Press. p. 334. ISBN 0-8223-2941-7.