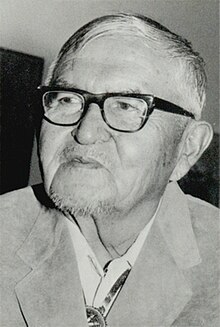

Allan Capron Houser or Haozous (June 30, 1914 – August 22, 1994) was a Chiricahua Apache sculptor, painter, and book illustrator born in Oklahoma.[2] He was one of the most renowned Native American painters and Modernist sculptors of the 20th century.

Allan Houser | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Allan Capron Houser[1] June 30, 1914 near Apache, Oklahoma |

| Died | August 22, 1994 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | Chiricahua Apache |

| Education | Studio at Santa Fe Indian School |

| Known for | Sculpture, Painting, Drawing, Murals |

Houser's work can be found at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, the National Museum of the American Indian, the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., the Oklahoma State Capitol Building, and in numerous major museum collections throughout North America, Europe, and Japan.[3] Additionally, Houser's Offering of the Sacred Pipe is on display at United States Mission to the United Nations in New York City.

Childhood and school days

editHouser was born in 1914 to Sam and Blossom Haozous on the family farm near Apache[4] and Fort Sill, Oklahoma, into the Warm Springs Chiricahua Apache tribe. Geronimo had led the tribe in battle, and would later rely on his grandnephew Sam Haozous (Allan's father) to serve as his translator.

In 1934, a 20-year-old Haozous left Oklahoma to study at Dorothy Dunn's Art Studio at the Santa Fe Indian School in Santa Fe, New Mexico.[4] Dunn's method encouraged working from personal memory, avoiding techniques of perspective or modeling, and stylization of Native iconography. For the latter, Allan Haozous made hundreds of drawings and canvasses in Santa Fe and was one of Dunn's top students, but he found the program too constricting.

Early career

editIn 1939, Houser began his professional career by showing work at the 1939 New York World's Fair and the Golden Gate International Exposition. He received his first major public commission to paint murals at the Main Interior Building in Washington, D.C. He married Anna Maria Gallegos of Santa Fe, his wife for 55 years.[4]

In 1940, he received another commission from the US Department of Interior to paint life-sized indoor murals. He then returned to Fort Sill to study with Swedish muralist Olle Nordmark, who encouraged Houser to explore sculpture. He made his first wood carvings that year.[1]

When World War II interrupted Houser's life and career path, he moved his growing family to Los Angeles where he found work in the L.A. shipyards. Houser worked by day and continued to paint and sculpt by night, making friends among students and faculty at the Pasadena Art Center. Here, he was first exposed to the streamlined modernist sculptural statements of artists like Jean Arp, Constantin Brâncuși, and the English sculptor Henry Moore. These three men – along with the English sculptor Barbara Hepworth, who was among the first sculptors to place sculptural voids within the solid planes of her works – would come to have a huge influence on Houser.

After World War II, Houser applied for a commission at the Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas. Haskell, a Native American boarding school, lost many graduates to the war and wanted a sculptural memorial to honor them. Though Houser had been carving in wood since 1940, he had never before sculpted in stone. He convinced the jury with his drawings and his conviction and completed the monumental work Comrade in Mourning from white Carrara marble in 1948.[5] It has become an iconic work, both for the artist and for Native American art in general.

Teaching

editIn 1949, Houser received a Guggenheim Fellowship in sculpture and painting, which granted him two years to work on art and still provide for his growing family.[6]

From 1952 to 1962, Houser worked as an art teacher at the Intermountain Indian School in Brigham City, Utah, which was primarily a Navajo boarding school.[7] The Intermountain years gave Houser time to teach, raise a family, and focus on his painting. He completed hundreds of paintings there, experimenting with watercolors, oils, and other media. While at Intermountain, he also worked as a children's book illustrator, providing drawings and paintings for seven titles – including an illustrated biography on the life of his grand-uncle Geronimo.[8] One of his notable students at the Intermountain Indian School was artist Robert Chee.[9]

In 1962, Houser was asked to join the faculty of a new Native American art school, the Institute of American Indian Arts. He returned to Santa Fe with his family to head up the Institute's sculpture department. Casting his first bronzes in 1967, Houser was a student and teacher as well, bringing forth his own history and ideas for a student body from every corner of Native America. He began working with the iconographies of other tribes, using modernist sculptural influences to forge the tribal and the abstract into a visual lexicon all his own.[citation needed]

During the early 1970s, Houser continued to teach at the Institute and began the rigorous production and exhibition cycle for which he became well known. As head of the sculpture department, he felt compelled to work in as many sculptural media as possible, evidenced by his solo exhibition of stone, bronze, and welded steel sculptures at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona in 1970.[10] The following year, Houser exhibited paintings and sculpture at the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, and in 1973 was awarded the Gold Medal in Sculpture at the Heard Museum Exhibition.[citation needed]

Exhibitions, awards, and accolades continued. In 1975, he was asked to paint the official portrait of former U.S. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall. That same year, he had a solo exhibition at the Governor's Gallery at the State Capitol in Santa Fe. After thirteen years at IAIA, Houser retired from full-time teaching to devote himself to sculpture.[citation needed]

Later work

editHouser's retirement in 1975 marked the beginning of the most prolific stage of his career. With time, materials, and the family compound in southern Santa Fe County, Houser honed the visual language that was to become his artistic legacy. Fusing Native subject matter with the abstract forms and sculptural voids of his Modernist peers, Houser carried the mantle of both Native American and Modernism to new levels, bringing forth such memorable images as the Lead Singer, Abstract Crown Dancer, and The Mystic.[citation needed]

Via Gambaro Gallery launched by Retha Walden Gambaro and Stephen Gambaro to spotlight contemporary Native American artists featured Houser's work in its Indian Artists, 1977 exhibition.[11] The exhibition credited Houser for influencing several generations of Native American artists and the success of sculpture as a contemporary Native American art form.[11]

Houser continued to produce figurative pieces as well, including the life-sized bronze work Chiricahua Apache Family, dedicated in 1983 at the Fort Sill Apache Tribal Center in Apache, Oklahoma. The piece honored both the memory of his parents, Sam and Blossom, and commemorates the 70th anniversary of the release of his tribe's prisoners-of-war from Fort Sill.[citation needed]

Houser's work was explored in a series on American Indian artists for the Public Broadcasting System (PBS). Other artists in the series included R. C. Gorman, Helen Hardin, Charles Loloma, Joseph Lonewolf, and Fritz Scholder.[12]

In 1985, Houser's monumental bronze, Offering of the Sacred Pipe, was dedicated at the U.S. Mission to the United Nations in New York City. A year later, he made a bronze bust of Geronimo to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the surrender of the Chiricahua Apaches. A cast of the bust was later presented to the National Portrait Gallery, where it remains in the permanent collection.[13]

In his last five years, Houser produced a remarkable number of pieces, and received many awards for his life's work. In 1989, he dedicated As Long as the Waters Flow, a monumental bronze commissioned for the Oklahoma State Capitol building in Oklahoma City. In 1991, he presented a casting of a bronze Sacred Rain Arrow to the Smithsonian Institution. In the dedication before the US Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs, he dedicated the work to the American Indian. And in 1992, he became the first Native American to receive the National Medal of Arts, awarded at a ceremony at the White House by President George H. W. Bush.[citation needed]

In 1993, Houser was honored by the dedication of the Allan Houser Art Park at the Institute of American Indian Arts,[3] and in 1994, he returned to Washington, DC for the last time to present the United States government the sculpture, May We Have Peace, a gift, he said, "To the people of the United States from the First Peoples." The gift was accepted by First Lady Hillary Clinton for installation at the Vice President's residence at Number One Observatory Circle.[citation needed]

Drawings

editHouser's primary skill as a draftsman is evident in the astounding volume of drawn work that was left behind in the Allan Houser Archive, located at the Houser family compound and sculpture garden in southern Santa Fe County, New Mexico. With over 6,000 images left behind, one can trace the output and varied subjects of an artist who began all of his creations, including paintings and sculptures, with the act of hand to paper.[citation needed]

Sculptures

editWhile Houser's early career was marked by his drawings and paintings, it was for sculpture that he eventually became a world-renowned artist. Beginning in 1940 with simple wood carvings, Houser created his first monumental work in stone in 1949, the iconic piece Comrades in Mourning at the Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas. In the following year, he would receive the Guggenhiem Fellowship.[14] However, it would be quite some time before he had the time and resources to produce more.[citation needed]

Collections

editAllan Houser's work can be found in collections all over the world. Below is a select list.

- Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, New Mexico

- Albuquerque International Sunport, New Mexico

- Allard School of Law, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

- Baker Museum, Artis–Naples, Naples, Florida

- Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming

- British Royal Collection, London, England

- Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France

- Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, Colorado Springs, Colorado

- Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire[15]

- Denver Art Museum, Denver, Colorado

- Eiteljorg Museum, Indianapolis, Indiana

- Haskell Indian Nations University, Lawrence, Kansas

- Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

- Institute of American Indian Arts Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico

- James A. Michener Art Museum, Doylestown, Pennsylvania

- Japanese Royal Collection, Tokyo, Japan

- National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

- National Museum of American Art, Washington, DC.

- National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC.

- National Museum of Wildlife Art, Jackson Hole, Wyoming

- National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.

- New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico[16]

- New Mexico State Capitol, Santa Fe, New Mexico

- Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Massachusetts

- Oklahoma State Capitol, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

- Palm Springs Desert Museum, California

- Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma

- Sundance Institute, Sundance, Utah

- U.S Mission at the United Nations, New York, New York

- University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma

- Wheelwright Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Legacy

editAllan Houser died of colon cancer in Santa Fe, New Mexico, at the age of eighty on August 22, 1994.[17]

The installation of 19 monumental works of art in Salt Lake City during the 2002 Olympics, and a retrospective of 69 works at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC. in 2004—2005 honored him. The exhibition marked the first major show for the new museum, and over three million people viewed it while it was on display.

His two sons have achieved success as sculptors, Philip Haozous and Bob Haozous, and his grandson, Sam Atakra Haozous, an experimental photographer. The non-profit Allan Houser Foundation is devoted to the proliferation of the Houser name. The family also maintains a commercial gallery of Allan Houser's work in downtown Santa Fe and the Allan Houser Compound, a foundry and sculpture garden located south of Santa Fe.[18]

In 2018, Houser became one of the inductees in the first induction ceremony held by the National Native American Hall of Fame.[19]

A figural group created by Houser in 1990 was moved to the Oval Office when Joe Biden began his presidency in 2021. The sculpture depicting a running horse and a Native male rider is currently placed on one of the shelves in the president's office and was previously exhibited at the National Museum of the American Indian.[20][21]

Exhibitions

editAllan Houser's work continues to receive academic and institutional exposure. His estate works with museums, art galleries, and public spaces around the world on ongoing exhibits. Houser's abstract and modernist works were exhibited at Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, New Jersey (2008), and his major works were shown at the Heard Museum and the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix, Arizona in November 2009. In 2008 the Oklahoma History Center held a major exhibition, "Unconquered: Allan Houser and the Legacy of one Apache Family," that looks at three generations of the Haozous/Houser family.[22]

Houser's work was part of Stretching the Canvas: Eight Decades of Native Painting (2019–21), a survey at the National Museum of the American Indian George Gustav Heye Center.[23]

Major collections of Allan Houser's work can also be found in museums around the United States and the world.

References

edit- ^ a b "Udall Department of the Interior Building: Houser Murals – Washington DC". The Living New Deal. University of California, Berkeley, Department of Geography. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "A Tribute." Archived 2011-04-21 at the Wayback Machine Allan Houser. Accessed March 26, 2011.

- ^ a b Houser, Allan (2020-11-04). "Raindrops". Public Sculpture and Installations.

- ^ a b c HOUSER (HAOZOUS), ALLAN (1914-1994). Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved March 30, 2011 Archived October 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gridley, Marion E. (1960). Indians of Today (Third ed.). Chicago: Towertown. p. 216.

- ^ "Artist Page". medallicartcollector.com. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ^ "Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art Houser Centennial Drawing Exhibit opens". artdaily.cc. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- ^ "Geronimo, the last Apache war chief / by Edgar Wyatt; illustrated by Allan Houser, direct descendant of Geronimo". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- ^ Worthington, G. Lola (26 May 2010). "Chee, Robert". Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t2086800. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. Archived from the original on 2018-06-03. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ "Allan Houser | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- ^ a b Gonyea, Ray, et al. Indian Artists, 1977 : An Exhibition, June 12 - September 10, 1977, via Gambaro Gallery. Via Gambaro Gallery, 1977.

- ^ Steven Leuthold, "13: Native American Art and Artists in Visual Arts Documentaries from 1973 to 1991," Archived 2020-06-15 at the Wayback Machine in On the Margins of Art Worlds, ed. Larry Gross. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1995, 268.

- ^ "Geronimo". npg.si.edu. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ^ "Native American Artist Biographies: Allan Houser Biography". www.bischoffsgallery.com. Retrieved 2023-11-04.

- ^ "Peaceful Serenity". Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "Allan Houser". New Mexico Museum of Art. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ "COLON CANCER CLAIMS SCULPTOR ALLAN HOUSER". Deseret News. Associated Press. August 24, 1994. Retrieved November 5, 2023. Republished in part as: "Allan Houser, 80, A Sculptor Known For Apache Themes". The New York Times. Associated Press. August 25, 1994. Retrieved November 5, 2023. "ALLAN HOUSER; NATIVE AMERICAN SCULPTOR". Hartford Courant. Associated Press. August 26, 1994. Retrieved November 5, 2023. "Allan Houser; Patriarch of Native American Sculptors". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. August 27, 1994. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ Allan Houser. (retrieved 27 Nov 2009)

- ^ "National Native American Hall of Fame names first twelve historic inductees - IndianCountryToday.com". Newsmaven.io. Archived from the original on 2018-10-22. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- ^ "Figural group | National Museum of the American Indian". americanindian.si.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ Linskey, Annie (20 January 2021). "A look inside Biden's Oval Office". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2021-01-20. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ "Unconquered: Allan Houser and the Legacy of one Apache Family." Archived 2010-02-06 at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma History Center. (retrieved 27 Nov 2009)

- ^ "Stretching the Canvas: Eight Decades of Native Painting". National Museum of the American Indian. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

External links

edit- Allan Houser's Official Website

- The Oklahoma Arts Council is pleased to announce the recent acquisition of Allan Houser's sculpture Dialogue. Currently on exhibit in the Betty Price Gallery.[1]

- "As Long as the Waters Flow": Allan Houser's Towering Tribute to the Spirit of Native Americans outside of the Oklahoma State Capital

- "Allan Houser: Join the centennial celebration of the birth of the world-famous Chiricahua Apache artist."

- Allan Houser: The Dean of Stone, video from Colores, New Mexico PBS, KNME.org