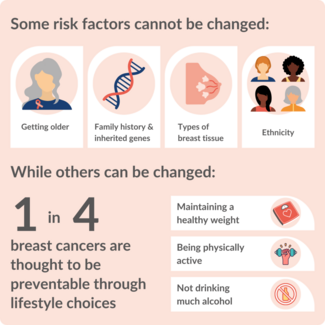

The relationship between alcohol and breast cancer is clear: drinking alcoholic beverages, including wine, beer, or liquor, is a risk factor for breast cancer, as well as some other forms of cancer.[1][2][3][4] Drinking alcohol causes more than 100,000 cases of breast cancer worldwide every year.[3] Globally, almost one in 10 cases of breast cancer is caused by women drinking alcoholic beverages.[3] Drinking alcoholic beverages is among the most common modifiable risk factors.[5]

The International Agency for Research on Cancer has declared that there is sufficient scientific evidence to classify alcoholic beverages a Group 1 carcinogen that causes breast cancer in women.[2] Group 1 carcinogens are the substances with the clearest scientific evidence that they cause cancer, such as smoking tobacco.

A woman drinking an average of two units of alcohol per day has 13% higher risk of developing breast cancer than a woman who drinks an average of one unit of alcohol per day.[6] Even light consumption of alcohol – one to three drinks per week – increases the risk of breast cancer.[3]

Heavy drinkers are also more likely to die from breast cancer than non-drinkers and light drinkers.[3][7] Also, the more alcohol a woman consumes, the more likely she is to be diagnosed with a recurrence after initial treatment.[7]

Mechanism

editThe mechanisms of increased breast cancer risk by alcohol are not clear, and may be:

- Increased estrogen and androgen levels[8]

- Enhanced mammary gland susceptibility to carcinogenics[8]

- Increased mammary DNA damage[8]

- Greater metastatic potential of breast cancer cells[8]

Their magnitude likely depends on the amount of alcohol consumed.[8]

Susceptibility to the breast cancer risk of alcohol may also be increased by other dietary factors (e.g. folate deficiency), lifestyle habits (including use of hormone replacement therapy), or biological characteristics (e.g. as hormone receptor expression in tumor cells).[8]

Light and moderate drinking

editDrinking alcoholic beverages increases the risk of breast cancer, even among very light drinkers (women drinking less than half of one alcoholic drink per day).[6] The risk is highest among heavy drinkers.[9]

Light drinking is one to three alcoholic drinks per week, and moderate drinking is about one drink per day. Both light and moderate drinking is associated with a higher risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer.[3][10] However, the increased risk caused by light drinking is smaller than the risk for heavy drinking.[11]

In daughters of drinking mothers

editStudies suggest that drinking alcohol during pregnancy may affect the likelihood of breast cancer in daughters. "For women who are pregnant, ingestion of alcohol, even in moderation, may lead to elevated circulating oestradiol levels, either through a reduction of melatonin or some other mechanism. This may then affect the developing mammary tissue such that the lifetime risk of breast cancer is raised in their daughters."[12]

Recurrence

editDrinking or not drinking alcohol does not solely determine whether breast cancer will recur after treatment.[7] However, the more a woman drinks, the more likely the cancer is to recur.[7]

In men

editIn men, breast cancer is rare, with an incidence of fewer than one case per 100,000 men.[13] Population studies have returned mixed results about excessive consumption of alcohol as a risk factor. One study suggests that alcohol consumption may increase risk at a rate of 16% per 10 g daily alcohol consumption.[14] Others have shown no effect at all, though these studies had small populations of alcoholics.[15]

Epidemiology

editWorldwide, alcohol consumption causes approximately 144,000 women to be diagnosed with breast cancer each year.[3] Approximately 38,000 women die from alcohol-induced breast cancer each year.[3] About 80% of these women were heavy or moderate drinkers.[3]

References

edit- ^ Hayes J, Richardson A, Frampton C (November 2013). "Population attributable risks for modifiable lifestyle factors and breast cancer in New Zealand women". Internal Medicine Journal. 43 (11): 1198–1204. doi:10.1111/imj.12256. ISSN 1445-5994. PMID 23910051. S2CID 23237732.

- ^ a b Alcohol consumption and ethyl carbamate International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (2007: Lyon, France) ISBN 9789283212966

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shield KD, Soerjomataram I, Rehm J (June 2016). "Alcohol Use and Breast Cancer: A Critical Review". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 40 (6): 1166–1181. doi:10.1111/acer.13071. ISSN 1530-0277. PMID 27130687.

- ^ Starek-Świechowicz B, Budziszewska B, Starek A (2022). "Alcohol and breast cancer". Pharmacological Reports: PR. 75 (1): 69–84. doi:10.1007/s43440-022-00426-4. ISSN 2299-5684. PMC 9889462. PMID 36310188.

- ^ McDonald JA, Goyal A, Terry MB (September 2013). "Alcohol Intake and Breast Cancer Risk: Weighing the Overall Evidence". Current Breast Cancer Reports. 5 (3): 208–221. doi:10.1007/s12609-013-0114-z. PMC 3832299. PMID 24265860.

- ^ a b Choi YJ, Myung SK, Lee JH (22 May 2017). "Light Alcohol Drinking and Risk of Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies". Cancer Research and Treatment. 50 (2): 474–487. doi:10.4143/crt.2017.094. ISSN 2005-9256. PMC 5912140. PMID 28546524.

- ^ a b c d Gou YJ, Xie DX, Yang KH, Liu YL, Zhang JH, Li B, He XD (2013). "Alcohol Consumption and Breast Cancer Survival: A Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 14 (8): 4785–90. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.8.4785. PMID 24083744.

Although our meta-analysis showed alcohol drinking was not associated with increased breast cancer mortality and recurrence, there seemed to be a dose-response relationship of alcohol consumption with breast cancer mortality and recurrence and alcohol consumption of >20 g/d was associated with increased breast cancer mortality.

- ^ a b c d e f Singletary KW, Gapstur SM (2001). "Alcohol and breast cancer: review of epidemiologic and experimental evidence and potential mechanisms". JAMA. 286 (17): 2143–51. doi:10.1001/jama.286.17.2143. PMID 11694156. S2CID 24160307.

- ^ Shield KD, Soerjomataram I, Rehm J (June 2016). "Alcohol Use and Breast Cancer: A Critical Review". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 40 (6): 1166–81. doi:10.1111/acer.13071. PMID 27130687.

All levels of evidence showed a risk relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of breast cancer, even at low levels of consumption.

- ^ Zhang SM, Lee IM, Manson JE, Cook NR, Willett WC, Buring JE (March 2007). "Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk in the Women's Health Study". Am J Epidemiol. 165 (6): 667–76. doi:10.1093/aje/kwk054. PMID 17204515.

- ^ Pelucchi C, Tramacere I, Boffetta P, Negri E, La Vecchia C (24 August 2011). "Alcohol Consumption and Cancer Risk". Nutrition and Cancer. 63 (7): 983–990. doi:10.1080/01635581.2011.596642. ISSN 0163-5581. PMID 21864055. S2CID 21395211. Archived from the original on 23 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ Stevens RG, Hilakivi-Clarke L (2001). "Alcohol exposure in utero and breast cancer risk later in life". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 36 (3): 276–7. doi:10.1093/alcalc/36.3.276. PMID 11373268.

- ^ "Male Breast Cancer". Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- ^ Guénel P, Cyr D, Sabroe S, Lynge E, Merletti F, Ahrens W, Baumgardt-Elms C, Ménégoz F, Olsson H, Paulsen S, Simonato L, Wingren G (August 2004). "Alcohol drinking may increase risk of breast cancer in men: a European population-based case-control study". Cancer Causes & Control. 15 (6): 571–580. doi:10.1023/B:CACO.0000036154.18162.43. ISSN 0957-5243. PMID 15280636. S2CID 23750821.

- ^ Brinton A, Richesson A, Gierach L, Lacey Jr R, Park Y, Hollenbeck R, Schatzkin A (October 2008). "Prospective evaluation of risk factors for male breast cancer". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 100 (20): 1477–1481. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn329. ISSN 0027-8874. PMC 2720728. PMID 18840816.

External links

edit- UK: Committee on Carcinogenicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products Consumption of alcoholic beverages and risk of breast cancer

- UK: Committee on Carcinogenicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products Evidence for association between consumption of alcoholic beverages and breast cancer