Alamo Crossing is a ghost town in Mohave County, Arizona, United States. The town was settled in the late 1890s, in what was then the Arizona Territory. It served as a camp for mining prospectors in the manganese-rich Artillery Mountains, being the only town in the area. After 1918, the post office permanently closed, but the town was only intermittently abandoned, with its founders often present through until at least the mid-1950s. The town was intentionally flooded in 1968 to create Alamo Lake. In 2020, the area of Alamo was revived for mining again, this time for surface-level gold prospecting.

Alamo Crossing, Arizona | |

|---|---|

Alamo Crossing | |

Location in the state of Arizona | |

| Coordinates: 34°15′38″N 113°34′58″W / 34.26056°N 113.58278°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Mohave |

| Founded | 1899 |

| Officially abandoned | 1918 |

| Founded by | Tom Rodgers |

| Elevation | 1,237 ft (377 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (MST (no DST)) |

History

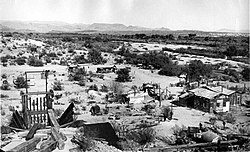

editFounded by Tom Rodgers in the late 1890s,[2] though the town road to Signal was supposedly built in 1860 (or earlier),[a][3] Alamo Crossing was never a big town.[2] It is on one side of the small Artillery Mountains range. Here there are many concentrated ore deposits,[3] and the town was founded as a non-permanent base for mining prospectors in the area, with the residents typically camping out.[2] During its heyday, the town only consisted of a five-stamp mill and a few stores. The town's post office opened on November 23, 1899, and was permanently closed on December 31, 1918.[4][5] The post office had previously closed on December 15, 1900, and was re-opened with the town name Alamo on March 30, 1911.[4]

The town was inconsistently abandoned through the 20th century: a 1949 account says that the Artillery Mountains area's "only inhabitants are a few prospectors and miners and two or three ranchers. The entire population in 1938 was probably less than 25 persons. Alamo is the only settlement, and at times even it is abandoned."[3] Local legend tells that Native Americans attacked the town, raiding the store and poisoning the storekeeper, and the postmaster soon after fled the town due to boredom, stealing the post office's money. The more likely truth is that the mines simply ran dry. In the early 1950s, during a manganese boom, the camp saw some revived interest,[2][4] and Alamo Crossing served as an important river crossing during this time,[6] but it was said to be soon abandoned again.[2][4]

The Rodgers brothers were still living in Alamo in 1928, when Al Rogers [sic] attests that the first manganese from the area was shipped in "about 11 cars" to Alabama.[3] They were also still around in 1949, and had many unpatented mine claims nearby. One, known as Oversight, was a few miles north of the town; it opened in 1952 and was shut down in 1954 after producing over 1,000 long tons (1,016.1 metric tons) of ore. Another was Mesa Manganese, with 27 mines in the claim, located about 17 miles (27.4 km) away but most easily accessible from Alamo. Discovered in 1949, Tom Rodgers and his mining prospector associate John M. Neal of Kingman, Arizona, leased the Mesa Manganese mines to a Californian company in 1953. It produced a few hundred tons of ore, much of which was processed in the area, but was also closed in 1954. Other 1950s, mine claims around Alamo Crossing include the Castenada group, the Shannon group, and the Black Burro group.[6]

Other residents in the 1940s–50s include Mr and Mrs George Lewis and a Mr Kimmel. The climate was such that Alamo often flooded for a few weeks during flood season.[3]

Alamo Crossing's population was 18 in the 1960 census.[7] In 1968, the Bill Williams River was dammed and the now-ghost town was submerged, with parts of the reservoir 80 feet (24 m) deep.[8]

Post-submersion

editIn 2020, new mines were opened around Alamo, with the British company Power Metal Resources (POW) having begun digging for gold nuggets after visiting the area and seeing "a 30 cm deep test 'pit' excavated and three small gold nuggets turned up with a borrowed metal detector".[9] Value the Markets's Tom Rodgers reported on the discovery, and how it was being touted as 'comedy gold' based on the unorthodox dig. He also noted that the POW share price increased 12%, reflecting that the site is owned as prospects by US firm Frisco Gold Corporation.[9] POW's shares continued to rise as it prospected the site through April 2020.[10]

Remains

editToday, the town is submerged at the bottom of Alamo Lake, with the small town of Alamo Lake, Arizona, nearby.[11] The remains of Alamo Crossing are still intact underwater.[8] Though almost untouched for 50 years, it was "one of the best preserved ghost towns in the state of Arizona" before it was flooded; the town road still exists, leading into the water.[5][8]

Rodgers family

edit- Thomas Jefferson Rodgers was born in California in July 1885. He died in Wickenburg, Arizona, on January 26, 1962, aged 76. He was buried in Kingman.[12]

- Robert Rodgers was born in Visalia, California, on April 24, 1892. He was also a miner, and moved to Wickenburg in 1957. He died in Wickenburg on December 21, 1962, at the age of 70, and was buried there.[12]

- May Kline (née Rodgers), who was living in Phoenix, Arizona, by 1962.[12]

- Sherman Rodgers, who was living in Wickenburg by 1962.[12]

- R. S. Rodgers, who owned the Last Chance mine claims, operating between 1953 and 1955.[6]

- E. S. Rodgers, who co-owned the Bob Allen/Black Duke mine claims in WWI.[6]

- J. E. Rodgers, who discovered the Blossom group mines in 1942.[6]

- John Rogers, who discovered the American group mines in 1939.[6]

- Al Rogers[3]

- Art Rodgers (Robert's son).[12] He died in Wickenburg on January 25, 2003, at the age of 70.[13]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ This road was surveyed in 1851 by Lorenzo Sitgreaves, as part of a wagon road across Arizona between the Zuni River and Colorado River.

References

edit- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Alamo Crossing (historical)

- ^ a b c d e Massey, Peter; Wilson, Jeanne Welburn (2006). Backcountry adventures: Arizona: the ultimate guide to the Arizona backcountry for anyone with a sport utility vehicle. Castle Rock, CO: Swagman Pub. p. 24. ISBN 1-930193-28-9. OCLC 70274768.

- ^ a b c d e f Lasky, Samuel Grossman; Webber, Benjamin N. (1949). Manganese Resources of the Artillery Mountains Region, Mohave County, Arizona. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ a b c d Sherman, James E.; Sherman, Barbara H.; Percious, Donald J. Ghost towns of Arizona (1st ed.). Norman. ISBN 0-8061-0842-8. OCLC 21732.

- ^ a b "Alamo Crossing – Arizona Ghost Town". Ghost Towns. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Farnham, Lloyd Lynn; Stewart, Lincoln Adair (1958). Manganese Deposits of Western Arizona. U.S. Bureau of Mines.

- ^ "Arizona". World Book Encyclopedia. Vol. A. Chicago: Field Enterprises Educational Corporation. 1960. p. 557.

- ^ a b c Lawrence, Katie (April 13, 2019). "Most People Have No Idea There's An Underwater Ghost Town Hiding In Arizona". OnlyInYourState. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "Power Metals looks to Alamo gold nuggets to reignite good times (POW)". Value the Markets. February 4, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ "Power Metal's Alamo Gold project expansion extends April run (POW)". Value the Markets. April 21, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Varney, Philip (1980). "Three: Ghosts of Central-Western Arizona • The Hot Ones". Arizona's Best Ghost Towns. Flagstaff: Northland Press. p. 42. ISBN 0873582179. LCCN 79-91724.

- ^ a b c d e "Wickenburg, Arizona, obituaries from the Wickenburg Sun". sites.rootsweb.com. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ AZ Central (2003). "Art Rodgers Obituary". Legacy.