Turanshah, also Turan Shah (Arabic: توران شاه), (? – 2 May 1250), (epithet: al-Malik al-Muazzam Ghayath al-Din Turanshah (Arabic: الملك المعظم غياث الدين توران شاه)) was a Kurdish ruler of Egypt, a son of Sultan As-Salih Ayyub. A member of the Ayyubid Dynasty, he became Sultan of Egypt for a brief period in 1249–50.

| Ghayath ad-Din Turanshah | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Malik al-Muazzam | |||||

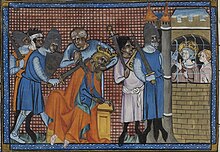

Picture of the assassination of Turanşah | |||||

| Sultan of Egypt | |||||

| Reign | 22 November 1249 – 2 May 1250 | ||||

| Predecessor | As-Salih Ayyub | ||||

| Successor | Shajar al-Durr | ||||

| Emir of Damascus | |||||

| Reign | 22 November 1249 – 2 May 1250 | ||||

| Predecessor | As-Salih Ayyub | ||||

| Successor | An-Nasir Yusuf | ||||

| Born | unknown | ||||

| Died | 2 May 1250 | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ayyubid dynasty | ||||

| Father | As-Salih Ayyub | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Background

editTuranshah was not trusted by his father, who sent him to Hasankeyf to keep him away from Egyptian politics.[1] He learned of his father's death from Faris ad-Din Aktai, commander of his father's Bahri Mamluks, who had been sent from Egypt to bring him back and pursue the war against Louis IX of France and the Seventh Crusade. Aktai arrived at Hasankeyf early in Ramadan 647/December 1249 and a few days later, 11 Ramadan/18 December, Turanshah and around fifty companions had started off for Egypt.[2] The party took a circuitous route to avoid being intercepted by hostile Ayyubid rivals and on 28 Ramadan 647/4 January 1250 they arrived at the village of Qusayr, near Damascus, making their ceremonial entry the next day, when Turanshah was officially proclaimed Sultan.[3]

Rule

editTuranshah remained in Damascus for three weeks, distributing huge sums of money to secure loyalty among the troops and notables of the city. He then set off for Egypt and arrived in Mansura with only a small retinue on 19 Dhu'l Qa'da/23 February. Ignoring his father's written advice to honour and rely on the Bahri Mamluks, he rapidly set about appointing his own (Muazzami) Mamluks to key positions.[4] He also promoted many black slaves to prominence. A black eunuch was made ustadar (master of the royal household) while another became amir jandar (master of the royal guard).[4] Both of these approaches alienated the powerful Bahri Mamluks.

The account given of Turanshah by historians writing during the Mamluk period cannot necessarily be relied on, but according to them, he was unbalanced, of low intelligence and had a nervous twitch.[4] On one occasion he went about chopping the tops off candles, shouting 'this is how I will deal with the Bahri Mamluks!' [4]

Turanshah led the Egyptian forces in the battle of Fariskur in 1250, the last battle of the Seventh Crusade. Here the Crusaders were totally defeated and Louis IX of France was captured.

Eventually the Bahris had had enough of him. They had been offended by Turanshah's treatment of them and, possibly, believed that once he had recovered Damietta from the Crusaders, he would turn against them. A faction of them, led by Baybars, resolved to kill him, and his murder was described in particular detail by crusader historian Jean de Joinville.[5]

Death

editOn 28 Muharram 648/2 May 1250, Turanshah gave a great banquet. At the end of the feast, Baibars and a group of Mamluk soldiers rushed in and tried to kill him. Turanshah was injured, as apparently a sword blow had split his hand open. Wounded, he managed to escape to a tower next to the Nile River. The Mamluks pursued him and set the tower on fire. He was forced down by the flames and tried to run for the river, but was struck in the ribs by a spear. He fled into the river, trailing the spear. His pursuers stood on the banks and shot at him with arrows, even as he begged for his life, offering to abdicate. Unable to kill him from the shore, Baibars himself waded out into the water and hacked the Sultan to death. It is said that Faris ad-Din Aktai then cut out his heart and took it to the captive Louis IX, hoping to receive a reward, which he did not.[5] According to some accounts it was in fact Aktai rather than Baibars who murdered him.[6]

Legacy

editTuranshah's father As-Salih Ayyub had been the last in the dynasty to exercise effective rule over Egypt and hegemony over the other Ayyubid domains. Turanshah was the last in the main Ayyubid line to rule in Egypt, with the exception of the six-year-old child Al Ashraf Musa, who was briefly installed as nominal Sultan by the Bahri Mamluk Aybak in a bid to present a veneer of Ayyubid legitimacy to Mamluk rule in Egypt at a time when the Syrian Ayyubids were threatening to invade.[7]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Irwin, Robert, The Middle East in the Middle Ages: The Early Mamluk Sultanate, 1250-1382, p.20.

- ^ Humphreys, R. Stephen, From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus 1193-1260, p.301

- ^ Humphreys, R. Stephen, From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus 1193-1260, p.302

- ^ a b c d Irwin, Robert, The Middle East in the Middle Ages: The Early Mamluk Sultanate, 1250-1382, p.21.

- ^ a b Wedgwood, Ethel (trans.) The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville: A New English Version Ethel Wedgwood, E.P. Dutton and Co., New York 1906, Chapter XV p. 172

- ^ Humphreys, R. Stephen, From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus 1193-1260, p.303

- ^ Humphreys, R. Stephen, From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus 1193-1260, p.315

Bibliography

edit- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (1995). Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Īlkhānid War,Ayyubid. Cambridge, Great Britain: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26. ISBN 0-521-46226-6.