This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (November 2013) |

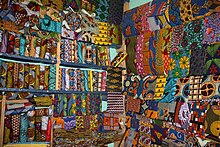

African wax prints, Dutch wax prints[1][2] or Ankara,[3] are a type of common material for clothing in West Africa. They were introduced to West Africans by Dutch merchants during the 19th century, who took inspiration from native Indonesian batik designs.[4] They began to adapt their designs and colours to suit the tastes of the African market. They are industrially produced colourful cotton cloths with batik-inspired printing.[5] One feature of these materials is the lack of difference in the colour intensity of the front and back sides. The wax fabric can be sorted into categories of quality due to the processes of manufacturing. The term "Ankara" originates from the Hausa name for Accra, the capital of what is now Ghana. Initially used by Nigerian Hausa tradesmen, it was meant to refer to "Accra," which served as a hub for African prints in the 19th century.[6]

Normally, the fabrics are sold in lengths of 12 yards (11 m) as "full piece" or 6 yards (5.5 m) as "half piece". The colours comply with local preferences of the customers. Typically, clothing for celebrations is made from this fabric.

Wax prints are a type of nonverbal communication among African women, and thereby carry their messages out into the world.[citation needed] Some wax prints are named after personalities, cities, buildings, sayings, or occasions. The producer, name of the product, and registration number of the design is printed on the selvage, thus protecting the design and attesting to the quality of the fabric. Wax fabrics constitute capital goods for African women. They are therefore often retained based on their perceived market value.

In Sub-Saharan Africa these textiles had an annual sales volume in 2016 of 2.1 billion yards, with an average production cost of $2.6 billion and retail value of $4 billion.[7]

Ghana has an annual consumption of textiles of about 130 million yards (120 million metres). The three largest local manufacturers, Akosombo Textiles Limited (ATL), Ghana Textiles Print (GTP), and Printex, produce 30 million yards, while 100 million yards come from inexpensive smuggled Asian imports.[8]

The Vlisco Group, owner of the Vlisco, Uniwax, Woodin, and GTP brands, produced 58.8 million yards (53.8 million meters) of fabric in 2011. Net sales were €225 million, or $291.65 million.[9] In 2014, Vlisco's 70 million yards of fabric (about 64 million meters) were produced in the Netherlands, yielding a turnover of €300 million.[10]

History

editThe process to make wax print is originally influenced by batik, an Indonesian (Javanese) method of dyeing cloth by using wax-resist techniques. For batik, wax is melted and then patterned across the blank cloth. From there, the cloth is soaked in dye, which is prevented from covering the entire cloth by the wax. If additional colours are required, the wax-and-soak process is repeated with new patterns.

During the Dutch colonization of Indonesia, Dutch merchants and administrators became familiar with the batik technique. Thanks to this contact, the owners of textile factories in the Netherlands, such as Jean Baptiste Theodore Prévinaire[11]: 16 and Pieter Fentener van Vlissingen,[12] received examples of batik textiles by the 1850s if not before, and started developing machine printing processes which could imitate batik. They hoped that these much cheaper machine-made imitations could outcompete the original batiks in the Indonesian market, effecting the look of batik without all the labor-intensive work required to make the real thing.

Prévinaire's attempt, part of a broader movement of industrial textile innovation in Haarlem, was the most successful. By 1854[11]: 16–17 he had modified a Perrotine, the mechanical block-printing machine invented in 1834 by Louis-Jérôme Perrot, to instead apply a resin to both sides of the cloth.[13]: 20 This mechanically applied resin took the place of the wax in the batik process.

Another method, used by several factories including Prévinaire's[11]: 18, 20 and van Vlissingen's,[12] used the roller printing technology invented in Scotland in the 1780s.

Unfortunately for the Dutch, these imitation wax-resist fabrics did not successfully penetrate the batik market. Among other obstacles, the imitations lacked the distinctive wax smell of the batik fabric.[11]: 17–18

Starting in the 1880s,[12][11]: 47, 50 they did, however, experience a strong reception in West Africa when Dutch and Scottish trading vessels began introducing the fabrics in those ports. Initial demand may have been driven by the taste for batik developed by the Belanda Hitam, West Africans recruited between 1831 and 1872 from the Dutch Gold Coast to serve in the Dutch colonializing army in Indonesia. Many members of the Belanda Hitam retired to Elmina, in modern Ghana, where they may have provided an early market for Dutch imitation batik.[11]: 41–46

The success of the trade in West Africa prompted other manufacturers, including Scottish, English, and Swiss manufacturers, to enter the market.

The Dutch wax prints quickly integrated themselves into African apparel, sometimes under names such as "Veritable Dutch Hollandais", and "Wax Hollandais". Women used the fabrics as a method of communication and expression, with certain patterns being used as a shared language, with widely understood meanings. Many patterns began receiving catchy names. Over time, the prints became more African-inspired, and African-owned by the mid-20th century. They also began to be used as formal wear by leaders, diplomats, and the wealthy population.

Wax-print cloth production

editPrévinaire's method for the production of imitation batik cloth proceeds as follows. A block-printing machine applies resin to both sides of the fabric. It is then submerged into the dye, in order to allow the dye to repel the resin covered parts of the fabric. This process is repeated, to build up a coloured design on the fabric. Multiple wooden stamp blocks would be needed for each colour within the design. The cloth is then boiled to remove the resin which is usually reused.[14]

Sometimes the resin on the cloth can be crinkled in order to form cracks or lines that are known as "crackles". The English- and Dutch-produced fabrics tended to have more cracking in the resin than those produced in Switzerland.[14] Due to the lengthy stages of its production, wax prints are more expensive to make than other commercial printed fabrics but their finished designs are clear on both sides and have distinct colour combinations.[13]: 15

Wax-print manufacturers

editAfter a merger in 1875, the company founded by Prévinaire became Haarlemsche Katoenmaatschappij (Haarlem Cotton Company). The Haarlemsche Katoenmaatschappij went bankrupt during the First World War, and its copper roller printing cylinders were bought by van Vlissingen's company.[11]: 20–21, 59

In 1927, van Vlissingen's company rebranded as Vlisco.

Before the 1960s most of the African wax fabric sold in West and Central Africa was manufactured in Europe. Today, Africa is home to the production of high quality wax prints.[15] Manufacturers across Africa include ABC Wax, Woodin, Uniwax, Akosombo Textiles Limited (ATL), and GTP (Ghana Textiles Printing Company), the latter three being part a part of the Vlisco Group.[16] These companies have helped reduce the prices of African wax prints in the continent when compared to European imports.

African fancy print

editThe costly produced wax fabrics are increasingly imitated by alternative ways of manufacturing. The so-called "fancy fabrics" are produced in a printing procedure. Costly designs are printed digitally.

Fancy fabrics in general are cheap, industrially produced imitations of the wax prints and are based on industry print. Fancy fabrics are also called imiwax, Java print, roller print, le fancy or le légos. These fabrics are produced for mass consumption and stand for ephemerality and caducity. Fancy Fabrics are more intense and rich in colours than wax prints and are printed on only one side.

As for wax prints, producer, product name and registration number of the design are printed on the selvage. Even the fancy fabrics vary with a certain fashion. The fabrics are limited to amount and design and are sometimes exclusively sold in own shops.

At first the fancy prints were made with engraved metal rollers but more recently they are produced using rotary screen-printing process.[15]

The production of these imitation wax-print fabrics, allow those who cannot afford the European imported wax prints to be able to purchase them. The fancy print designs often mimic or copy the designs of existing wax print designs but as they are cheaper to make, manufacturers tend to take risks and experiment with new designs.[15]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Sylvanus, Nina (29 August 2016). "West Africans ditch Dutch wax prints for Chinese 'real-fakes'". The Conversation. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (16 September 2021). "'This has never been so much fun!': Royal Academy Summer Exhibition review". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "900+ Ankara ideas in 2022 | african clothing, african fashion dresses, african dress". Pinterest. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "A PIECE OF HISTORY- THE AKWETE FABRIC". Guardian. Nigeria. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Gerlich 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Things To Consider Before Buying African Ankara Print Fabrics, Clothing, Headwraps and more, Afrothreads, retrieved 21 December 2023

- ^ Aibueku, Uyi (16 February 2016). "In textile industry, a hidden goldmine". The Guardian. Nigeria. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "Textile industry needs attention to boost local manufacturing". My Joy Online. 19 September 2017. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ Young, Robb (15 November 2012). "Africa's Fabric Is Dutch". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "Wax prints, like Vlisco, are still making believe that they are African". Yen.com.gh. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kroese, W.T. (1976). The origin of the Wax Block Prints on the Coast of West Africa. Hengelo: Smit. ISBN 9062895018.

- ^ a b c "The Founding of Vlisco". Vlisco. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ a b LaGamma, Alisa (2009). The Essential Art of African Textiles: Design Without End. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ a b Gillow, John (2009). Printed and Dyed textiles from Africa. London: The British Museum Press. p. 18.

- ^ a b c Magie, Relph; Irwin, Robert (2010). African wax print: a textile journey. Meltham: Words and Pixels for the African Fabric Shop. p. 32. ISBN 9780956698209. OCLC 751824945.

- ^ "About GTP - GTP Fashion". GTP Fashion. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

Literature

edit- Gerlich, G. (2004). Waxprints im soziokulturellen Kontext Ghanas. Arbeitspapier Nr. 54 (PDF). Institut für Ethnologie und Afrikastudien. Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013.

- Gillow, J. (2003). African textiles. Colour and creativity across a continent. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

- Joseph, M. L.: Introductory Textile Science. 2. Aufl. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1972.

- Luttmann, I. (2005). "Die Produktion von Mode: Stile und Bedeutungen". In Luttmann, Ilsemargret (ed.). Mode in Afrika. Mode als Mittel der Selbstinszenierung und Ausdruck der Moderne. Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg. pp. 33–42.

- Picton, J. (1995). "Technology, tradition and lurex: The art of textiles in Africa". In Picton, John (ed.). The art of African textiles. Technology, tradition and lurex. London: Lund Humphries Publishers. pp. 9–32, 132.

- Rabine, Lesley W. (1 November 2002). The global circulation of African fashion. Oxford: Berg. ISBN 978-1-85973-598-5.

- Schädler, Karl F. (1997). Afrikanische Kunst. Von der Frühzeit bis heute [African Art. From the early days until today] (in German). Munich: Wilhelm Heyne Verlag. ISBN 9783453130456.

- Sarlay, A., Jurkowitsch, S.: "Entdecken der Vorarlberger Stickereien in Westafrika", Wirtschaftskammer Vorarlberg, 2009.

- Sarlay, A.; Jurkowitsch, S. "An analysis of the current denotation and role of Wax & Fancy fabrics in the world of African textiles". International Journal of Management Cases. 1/2010 (22): 28–48.

- Storey, J. (1974). Manual of Textile Printing. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

- Koné, F. B. (2000). "Das Färben von Stoffen in Bamako". In Gardi, Bernhard (ed.). Boubou c´est chic. Gewänder aus Mali und anderen Ländern Westafrikas. Museum der Kulturen Basel (in German). Basel: Christoph Merian Verlag. pp. 164–171.