Achaemenid Macedonia refers to the period in which the ancient Greek Kingdom of Macedonia was under the reign of the Achaemenid Persians. In 512/511 BC, the Persian general Megabyzus forced the Macedonian king Amyntas I to make his kingdom a vassal of the Achaemenids. In 492 BC, following the Ionian Revolt, the Persian general Mardonius firmly re-tightened the Persian grip in the Balkans, making Macedon a fully subordinate kingdom within the Achaemenid domains and part of its administrative system. Macedonia served the Achaemenid Empire during the Greco-Persian Wars in their invasion of mainland Greece. They regained independence following the defeat and withdrawal of the Achaemenid Empire in 479 BC.

Achaemenid Macedonia Αχαιμενιδών Μακεδονία | |

|---|---|

| 512/511–499 BC, 492–479 BC | |

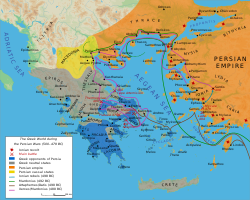

Macedonia as a Persian vassal kingdom during the early stages of the Greco-Persian Wars | |

| Capital | Aigai[1] |

| Common languages | Ancient Macedonian, Attic Greek, Old Persian |

| Government |

|

| King | |

| Historical era | Classical Antiquity |

• Macedon becomes a vassal kingdom under Darius I | 512/511–499 BC |

• Macedon becomes a fully subordinate part of Persia.[2] | 492–479 BC |

• Conclusion of the Second Persian invasion of Greece | 479 BC |

• Macedon gains independence from Persia.[2] | 479 BC |

| Currency | Daric, Siglos, Tetradrachm |

512/511 BC: Achaemenid vassal state

editAround 513 BC, as part of the military incursions ordered by Darius I, a huge Achaemenid army invaded the Balkans and tried to defeat the Western Scythians roaming to the north of the Danube river. Several Thracian peoples, and nearly all of the other European regions bordering the Black Sea (including parts of modern-day Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine and Russia), were conquered by the Achaemenid army before it returned to Asia Minor.[3]

Darius's highly regarded commander, Megabyzus, was responsible for conquering the Balkans.[3] The Achaemenid troops conquered Thrace, the coastal Greek cities, and the Paeonians.[3][4][5] Eventually, in about 512/511 BC, the Macedonian king Amyntas I accepted the Achaemenid domination and submitted his country as a vassal state to Achaemenid Persia.[3][5][6][7] Megabazus received the present of "Earth and Water" from Amyntas, which symbolized submission to the Achaemenid Emperor.[8]

The multi-ethnic Achaemenid army possessed many soldiers from the Balkans. Moreover, many of the Macedonian and Persian elite intermarried. For instance, Megabazus' own son, Bubares, married Amyntas' daughter Gygaea,[3] with the intention of ensuring good relations between the Macedonian and Achaemenid rulers and reinforcing the alliance.[3][8]

492–479 BC: Achaemenid suzerainty

editFollowing the collapse of the Ionian Revolt, Persian authority in the Balkans was restored by Mardonius in 492 BC,[9] which not only included the re-subjugation of Thrace, but also the inclusion of Macedon as part of the Persian Empire under the satrapy of Skudra.[10] According to Herodotus, Mardonius' main task was to force the suzerainty of Athens and Eretria, along with as many other Greek cities as possible.[11]

After having crossed to Europe, Mardonius and his army reached the Persian garrison of Doriscus, and from there, the army separated. The Persian navy brought Thasos under Persian suzerainty, while the infantry continued its way towards Mount Pangaeum, and after crossing the Angites, entered the lands of the Paeonians and re-asserted Persian suzerainty there. Heading towards the Thermaic Gulf, the infantry and the navy encountered difficulties; the former was attacked at night by the Byrgi, while a strong storm devastated the latter. The Byrgi were eventually subdued and the remaining Persian navy continued the campaign. Having arrived at the eastern border of Macedon, Alexander I of Macedon was forced to acknowledge Persian suzerainty over his kingdom.[12] As a result of Mardonius' campaign, Macedonia was incorporated into the administrative system of Persia.[13] As Herodotus mentions in his Histories; "and with their army they added the Macedonians to the already existing slaves [of the Persians]; for all the peoples on their side of Macedonia had already been subjected to them".[9][14]

The Persian invasion led indirectly to Macedonia's later rise in power as Persia and Macedon had some common interests in the Balkans. Thanks to the Persians, the Macedonians stood to gain much at the expense of some of the Balkan tribes such as the Paeonians and Thracians. All in all, the Macedonians were "willing and useful Persian allies".[9] Macedonian soldiers fought against Athens and Sparta in Xerxes' army.[15] In Macedon, abundant food supplies of the Persians were stored during their rule. Due to the scarce resources available in Macedon at that time, it is debatable whether Macedon hosted any Persian garrisons.[16]

Although Persian rule in the Balkans was overthrown following the failure of Xerxes' invasion of Greece, the Macedonians (and Thracians) borrowed heavily from the Achaemenid Persian traditions, culture and economy during the fifth to mid fourth centuries BC. Some artefacts, excavated at Sindos and Vergina may be considered as influenced by Persian culture, or even imported from Persia in the late sixth and early fifth centuries BC.[15]

References

edit- ^ Roisman & Worthington 2011, Chapter 5: Johannes Engels, "Macedonians and Greeks", p. 92.

- ^ a b Roisman & Worthington 2011, pp. 135–138, 342–345.

- ^ a b c d e f Roisman & Worthington 2011, p. 343.

- ^ Howe & Reames 2008, p. 239.

- ^ a b "Persian influence on Greece (2)". Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Fox 2011, p. 85.

- ^ Roisman & Worthington 2011.

- ^ a b Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9781107009608.

- ^ a b c Roisman & Worthington 2011, p. 344.

- ^ Herodotus VI 44

- ^ Vasilev 2015, p. 142.

- ^ Vasilev 2015, p. 154.

- ^ Vasilev 2015, p. 156.

- ^ Herodotus 2010, p. 425.

- ^ a b Roisman & Worthington 2011, p. 345.

- ^ Vasilev 2015, p. 157.

Sources

edit- Fox, Robin J. L. (2011). Brill's Companion to Ancient Macedon: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Macedon, 650 BC - 300 AD. BRILL. ISBN 978-9-00-420650-2.

- Herodotus (2010). Grene, David (ed.). The History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-22-632775-4.

- Howe, Timothy; Reames, Jeanne (2008). Macedonian Legacies: Studies in Ancient Macedonian History and Culture in Honor of Eugene N. Borza. Regina Books. ISBN 978-1-930-05356-4.

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-44-435163-7.

- Vasilev, Miroslav Ivanov (2015). The Policy of Darius and Xerxes towards Thrace and Macedonia. BRILL. ISBN 978-9-00-428215-5.