A Thief in the Night is a 1973 American evangelical Christian horror film written by Jim Grant, and directed and produced by Donald W. Thompson. The film stars Patty Dunning, with Thom Rachford, Colleen Niday and Mike Niday in supporting roles. The first installment in the Thief in the Night series about the Rapture and the Tribulation, the plot is set during the near future, focusing on a young woman who, after being left behind, struggles to decide what to do in the face of the Tribulation.

| A Thief in the Night | |

|---|---|

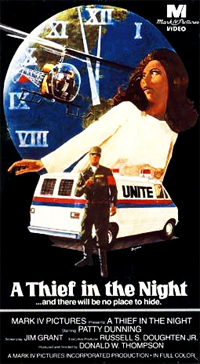

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Donald W. Thompson |

| Written by | Jim Grant |

| Produced by | Donald W. Thompson |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | John P. Leiendecker Jr. |

| Edited by | Wes Phillippi |

Production company | Mark IV Pictures |

| Distributed by | Mark IV Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 69 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $68,000 |

Three sequels were produced: A Distant Thunder (1978), Image of the Beast (1981), and The Prodigal Planet (1983). An additional three follow-ups were planned but ultimately unproduced.

The film has been highly influential in the evangelical film industry and American evangelical youth culture.[1]

Plot

editIn medias res, Patty Myers awakens to a radio broadcast announcing the disappearance of millions around the world. The radio announcer suggests that this might be the rapture of the Church spoken of in the Bible. Patty, a member of a liberal church, finds that her husband, a born-again Christian, has also disappeared. The United Nations sets up an emergency government system called the United Nations Imperium of Total Emergency (UNITE) and declares that anyone who does not receive the mark of the beast identifying them with UNITE will be arrested.

Several flashbacks occur to times in Patty's life before the Rapture. The story begins with Patty and her two friends, who all have different destinies. Her friend Jenny considers Jesus Christ her Savior; her other friend Diane is more worldly-minded. Patty considers herself a Christian because she occasionally reads her Bible and goes to church regularly; however, her pastor is shown to be an unbeliever. She refuses to believe the warnings of her friends and family that she will go through the Great Tribulation if she does not put her faith in Christ. Meanwhile, her husband has been attending another church and has accepted Jesus. The next morning, Patty awakens to find that her husband and millions of others have suddenly disappeared.

Patty is conflicted: she refuses to trust Christ, yet she also refuses to take the Mark. She desperately tries to avoid UNITE and the Mark but is eventually captured. She escapes, but after a chase she is cornered by UNITE on a bridge and falls from the bridge to her death.

Patty awakens and realizes it has all been a dream. She is relieved, but her relief is short-lived when the radio announces that millions of people have in fact disappeared. Horrified, Patty frantically searches for her husband only to find he is missing too. Patty realizes that the Rapture has actually occurred and she has been left behind.

Cast

edit- Patty Dunning as Patty Myers

- Mike Niday as Jim Wright

- Colleen Niday as Jenny

- Maryann Rachford as Diane Bradford

- Thom Rachford as Jerry Bradford

- Duane Coller as Duane

- Russell Doughten as Rev. Matthew Turner

- Clarence Balmer as Pastor Balmer

- Gareld L Jackson as UNITE Leader

- Herb Brown as UNITE Officer

- Herb Brown, Jr as UNITE Officer

- Betty D. Jackson as Wedding Guest

Themes

editThe film's title is taken from 1 Thessalonians 5:2, in which Paul warns his readers that "the day of the Lord so cometh as a thief in the night."

A Thief in the Night presents a pre-tribulational dispensational futurist interpretation of Christian eschatology and the rapture popular among U.S. evangelicals, but is generally rejected by Roman Catholics,[2] Orthodox Christians,[3] Lutherans, and Reformed Christians.[4] According to Dean Anderson of Christianity Today, "the film brings to life the dispensational view of Matthew 24:36-44."[5]

Casual connections to Christianity and liberal theological beliefs are depicted as insufficient forms of the faith, with Patty's born-again Christian husband being raptured and Patty, herself part of a liberal church, left behind.[6]

In the film, everyone must receive the mark of the beast on their forehead or right hand in order to buy or sell.[7]: 185 Producers used three rows of a binary number six ("0110") to represent the number 666, an interpretation of Revelation 13:11-18.[8]: 207 The locusts from Revelation 9 with human faces, ready for battle – to torment those without the seal of God – are represented in the film as attack helicopters, taken from Christian writer Hal Lindsey's understanding of the end times.[1][9]

Fears of globalism and big government are prominent themes in the film, with "the Antichrist...literally a branch of the United Nations claiming control over the entire world."[10]

Production

editBackground

editIn 1972, Iowa-based filmmakers Russell Doughten and Donald W. Thompson formed Mark IV Pictures to produce A Thief in the Night.[11]: 577-578 Thompson had been working in radio,[12]: 69 and Doughten had worked with Good News Productions on The Blob in 1958,[13] and had produced other films in Iowa through his production company Heartland Productions.[14]: 7-8 The film's actors had little to no previous professional acting experience.[1]

Filming

editPrincipal photography took place entirely on location in Iowa, with scenes being shot in Carlisle, the Iowa State Fair, and at Red Rock dam.[14]: 83

Music

editThe film's title track "I Wish We'd All Been Ready", composed by singer and musician Larry Norman, is performed in the film by The Fishmarket Combo, a band made up of local student volunteers.[5][1] The song went on to become the anthem of the Jesus movement.[12]: 411

Influences

editChristian writer Hal Lindsey's 1970 non-fiction book The Late Great Planet Earth was an influence on the film and its Rapture depictions; Thief has been described as complementing Lindsey's book.[1][9]

Reception

editProduced on a $68,000 budget, A Thief in the Night earned an estimated $4.2 million during its first decade of release, the majority of which came from audience donations. It was "one of the first films to take on fundamentalist apocalyptic narratives within a fictional motif."[8]: 92

Legacy

editThe film has been translated into three languages and subtitled in others. In 1989, historian of religion Randall Balmer wrote that producer Doughten estimated that 100 million people had seen the film.[12]: 62 More recently, Dean Anderson writing for Christianity Today says it has been seen by an estimated 300 million.[5] Christian Bookstore Journal listed it as the top-selling Christian video from 1990 to 1995.[6]

A pioneer in the genre of Christian film, the film brought rock music and elements of horror to a genre then-dominated by family-friendly evangelicalism.[5] Balmer has stated that "It is only a slight exaggeration to say that A Thief in the Night affected the evangelical film industry the way that sound or color affected Hollywood."[12]: 65 MIT professor of film and media Heather Hendershot says, "Today, many teen evangelicals have not seen A Thief in the Night, but virtually every evangelical over thirty I've talked to is familiar with it, and most have seen it... I have found that A Thief in the Night is the only evangelical film that viewers cite directly and repeatedly as provoking a conversion experience."[7]: 187-188 The film has been described by religion scholar Timothy Beal as having "tremendous influence on the emergence of evangelical horror"; Beal also compares aspects of Thief, such as UNITE and the zombie-like characters who have taken the mark, to Night of the Living Dead.[1]

It has been described as traumatic for children, who comprised a significant percentage of its original audience, and criticized for using scare tactics to produce religious conversions. A prayer to ask Jesus into one's heart depicted in the film serves as a template for viewers.[15][1] According to Hendershot, "Evangelicals who grew up in the 1970s or early 1980s often cite Thief as a source of childhood terror." This is partly due to depictions in the film of characters who believe themselves to be saved but are not, and are instead left behind.[7]: 187 The film has been mentioned in online discourse of Rapture anxiety.[10]

A quarter century later, the authors of the Left Behind franchise have acknowledged their debt to Thief.[1] Indeed, even the title Left Behind echoes the refrain of Norman's theme song for A Thief in the Night, "I Wish We'd All Been Ready": "There's no time to change your mind, the Son has come and you've been left behind."[5]

Sequels

edit- A Distant Thunder (1978)

- Image of the Beast (1981)

- The Prodigal Planet (1983)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Beal, Timothy (September 21, 2023). "The Rise and Fall of Evangelical Protestant Apocalyptic Horror: From A Thief in the Night to Left Behind and Beyond". In Gastón, Espinosa; Redling, Erik; Stevens, Jason (eds.). Protestants on Screen: Religion, Politics and Aesthetics in European and American Movies (Online ed.). New York: Oxford Academic. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190058906.003.0018.

- ^ Guinan, Michael D. (October 2005), "Raptured or Not? A Catholic Understanding", archived from the original on February 26, 2014, retrieved February 8, 2021

- ^ Coniaris, Anthony M. (September 12, 2005), The Rapture: Why the Orthodox Don't Preach It, Light & Life Publishing, archived from the original on November 9, 2012, retrieved February 8, 2021

- ^ Schwertley, Brian M., Is the Pretribulation Rapture Biblical?, Reformed Online, archived from the original on March 11, 2013, retrieved February 8, 2021

- ^ a b c d e Anderson, Dean A. (March 7, 2012). "The original "Left Behind"". christianitytoday.com. Christianity Today. Archived from the original on April 16, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Clark, Lynn Schofield (2005). "Angels, Aliens, and the Dark Side of Evangelicalism". From Angels to Aliens: Teenagers, the Media, and the Supernatural (Online ed.). Oxford Academic. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195300239.003.0002.

- ^ a b c Hendershot, Heather (2010). Shaking the World for Jesus, Media and Conservative Evangelical Culture. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-32679-5. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Edwards, Jonathan J. (2015). Superchurch: The Rhetoric and Politics of American Fundamentalism. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-1-62895-170-7. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Mollett, Margaret (2014). "Telescopic Reiteration". Religion & Theology. 21 (3–4). doi:10.1163/15743012-02103009. ISSN 1023-0807.

- ^ a b Burton, Tara Isabella (December 13, 2017). "#RaptureAnxiety calls out evangelicals' toxic obsession with the end times". Vox. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ Balmer, Randall (2002). Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-22409-1. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Balmer, Randall (2014). Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: A Journey Into the Evangelical Subculture in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-936046-8. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Albright, Brian (2012). Regional Horror Films, 1958-1990: A State-by-State Guide with Interviews. McFarland & Company. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-7864-7227-7. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Knepper, Marty; Lawrence, John (2014). The Book of Iowa Films. ISBN 978-0-9904289-1-6. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ "Iowa's 'A Thief in the Night': Not Just a Horror Flick". Iowa Public Radio. December 13, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

External links

edit- A Thief in the Night at the Internet Movie Database

- Film review by G. Noel Gross Archived 2005-04-29 at the Wayback Machine, January 3, 2002

- Official website