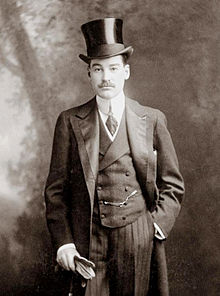

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt Sr. (October 20, 1877 – May 7, 1915) was an American businessman and member of the Vanderbilt family. A sportsman, he participated in and pioneered a number of related endeavors. He died in the sinking of the RMS Lusitania, on 7 May 1915, after being torpedoed by a German submarine (SM U-20).[1]

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 20, 1877 New York City, United States |

| Died | May 7, 1915 (aged 37) Atlantic Ocean |

| Education | St. Paul's School |

| Alma mater | Yale University (1899) |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Ellen Tuck French

(m. 1901; div. 1908)Margaret Mary Emerson

(m. 1911) |

| Children | William Henry Vanderbilt III Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt Jr. George Washington Vanderbilt III |

| Parent(s) | Cornelius Vanderbilt II Alice Claypoole Gwynne |

| Relatives | See Vanderbilt family |

Early life

editVanderbilt was born in New York City, the third son of Cornelius Vanderbilt II (1843–1899) and Alice Claypoole Gwynne (1845–1934). His siblings were Alice Gwynne Vanderbilt (1869–1874), William Henry Vanderbilt II (1870–1892), Cornelius "Neily" Vanderbilt III (1873–1942), Gertrude Vanderbilt (1875–1942), Reginald Claypoole Vanderbilt (1880–1925) and Gladys Moore Vanderbilt (1886–1965).[citation needed]

Alfred Vanderbilt attended the St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire, and Yale University (Class of 1899),[2] where he was a member of Skull and Bones.[3] Soon after graduation, Vanderbilt, with a party of friends, started on a tour of the world which was to have lasted two years. When the group reached Japan on September 12, 1899, he received news of his father's sudden death and hastened home as speedily as possible to find himself, by his father's will, the head of his branch of the family.[2][3]

His eldest brother, William, had died in 1892 at age 22, and their father had disinherited Alfred's second-oldest brother Neily due to his marriage to Grace Wilson, a young debutante of whom the elder Vanderbilts strongly disapproved for a variety of reasons. Alfred received the largest share of his father's estate, though it was also divided among his sisters and his younger brother, Reginald.[1]

Career

editSoon after his return to New York, Vanderbilt began working as a clerk in the offices of the New York Central Railroad as preparation for entering into the councils of the company as one of its principal owners. Subsequently, he was chosen a director in other companies as well, among them the Fulton Chain Railway Company, Fulton Navigation Company, Raquette Lake Railway Company, Raquette Lake Transportation Company, and the Plaza Bank of New York.[citation needed]

Vanderbilt was a good judge of real estate values and projected several important enterprises. On the site of the former residence of the Vanderbilt family and on several adjacent plots, he built the Vanderbilt Hotel at Park Avenue and 34th Street, New York, which he made his city home.[2][4]

Among Vanderbilt's many holdings were positions in the New York Central Railroad, Beech Creek Railroad, Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway, Michigan Central Railroad and Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad as well as the Pullman Company.[5]

Personal life

editOn January 11, 1901, Vanderbilt married Ellen ("Elsie") Tuck French, in Newport, Rhode Island. She was the daughter of Francis Ormond French (1837–1893) and his wife Ellen Tuck (1838–1915), and was close friends with Vanderbilt's sister, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who was married to Harry Payne Whitney.[3][6][7] Later that same year, on November 24, 1901, Elsie gave birth to their only child: William Henry Vanderbilt III (1901–1981), later governor of Rhode Island.[8][9]

In March 1908, Elsie moved to the home of her brother, Amos Tuck French, in Tuxedo Park, New York.[10] Shortly thereafter, a scandal erupted in April 1908 after Elsie filed for divorce, alleging adultery with Agnes O'Brien Ruíz, the wife of the Cuban attaché in Washington, D. C.[11][12][13] The publicity, which caused splits over whom to support,[14] ultimately led Agnes Ruíz to commit suicide in 1909.[15][16] Elsie, who remarried, died in Newport on February 27, 1948.

Vanderbilt spent considerable time in London after the divorce,[17] and he remarried there, on December 17, 1911,[18][19] to the wealthy American divorcée Margaret Mary Emerson (1886–1960).[20] She was the daughter of Captain Isaac Edward Emerson (1859–1931) and Emily Askew Dunn (1854–1921), and was heiress to the Bromo-Seltzer fortune.[21] Margaret had been married from 1902 to 1910 to Dr. Smith Hollins McKim (d. 1932),[22][23] a wealthy physician of Baltimore.[24][25] Together, Alfred and Margaret had two children: Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt Jr. (1912–1999),[26] a businessman and racehorse breeder,[27] and George Washington Vanderbilt III (1914–1961), a yachtsman and scientific explorer.[28]

After Alfred's death aboard the Lusitania in 1915, Margaret bought a 316-acre estate in Lenox, Massachusetts, with a 47-room mansion. She remarried twice, first on June 12, 1918, in Lenox to Raymond T. Baker (1875–1935), a politician with whom she had a daughter, Gloria Baker (1920–1975).[29] The claim for Alfred's estate was put forward by Margaret, who by that point was already remarried. Estimates as to the size of the Estate vary, with many sources using the 1917 Appraisal of the Estate in the Surrogate's Court of New York, which put the net value of the estate in the State of New York, after the payment of all debts and funeral and administration expenses, at $15,594,836.32 (equivalent to $273,537,014 in 2023).[30] In 1964, Edwin Hoyt's book The Vanderbilts and their Fortunes records the total size of Alfred's estate at $26,375,000,[31] exclusive of the $6,000,000 he gifted to his brother Cornelius Vanderbilt III following their father's death, and the $10,000,000 his first wife received after their divorce. From this amount, $8,000,000 was left to Alfred's second wife Margaret ($5,100,930 of this in New York),[32]$500,000 to his brother Reginald, $5,000,000 and the Oakland Farm Estate to Alfred's oldest son William H. Vanderbilt III, with the residuary estate being split between his two younger sons Alfred G. Vanderbilt Jr and George Washington Vanderbilt III, whose shares were estimated at $2,553,204 in 1917.[33]

Contemporary newspaper articles reporting on the 1917 appraisal of Alfred's estate in the State of New York report that Alfred's gross estate was valued at $16,769,314, in addition to a Trust Fund valued at $4,612,086, with a net value of approximately $15,594,000; from this his oldest son William H. Vanderbilt III received the $4,612,086 in Trust, as well as a life interest in $400,000, and the Medal which Congress had gifted to Cornelius 'the Commodore' Vanderbilt I which had been passed first to William Henry Vanderbilt, Cornelius Vanderbilt II, and then to Alfred.[32]

By the terms of Alfred's will, Margaret and his three sons would inherit $1,180,098.18 (equivalent to $20,699,193 in 2023). In addition, for their maintenance and for the support and comfort of his widow and children, he expended and contributed approximately $300,000 (equivalent to $5,262,069 in 2023) annually.[34][20][35]

Interests

editVanderbilt was a sportsman, and he particularly enjoyed fox hunting and coaching.[3][10] In the late 19th century, he and a number of other millionaires, such as James Hazen Hyde practiced the old English coaching techniques of the early 19th century. Meeting near Holland House in London, the coaching group would take their vehicle for a one-day, two-day, or longer trip along chosen routes through several counties, going to prearranged inns and hotels along the routes. Vanderbilt would frequently drive the coach, in perfectly appareled suit, a coachman or groom.[15] He is recorded as a regular guest at the Burford Bridge Hotel near Box Hill in Surrey where, when driving from London to Brighton, he would stop to take lunch and to collect telegrams.[36][37] He loved the outdoor experience.[15]

Vanderbilt was a member of the Coaching Club of New York and his coach, which was named Venture, was custom built in 1903 by coachbuilders Brewster & Co. The coach, actually a "heavy park drag – made road style" was restored by the Preservation Society of Newport County and is on display at The Breakers.[38][39][40]

In 1902,[41] he bought Great Camp Sagamore, on Sagamore Lake in the Adirondacks, from William West Durant.[42] He expanded and improved the property to include flush toilets, a sewer system, and hot and cold running water. He later added a hydroelectric plant and an outdoor bowling alley with an ingenious system for retrieving the balls. Other amenities included a tennis court, a croquet lawn, a 100,000 gallon reservoir, and a working farm.[1][43]

In 1908, he donated $100,000 to build the Mary Street YMCA (today the Vanderbilt Hotel) in Newport, Rhode Island, in memory of his father Cornelius Vanderbilt II (1843–1899). Ground breaking was on August 31, 1908, with the cornerstone laid on November 19, 1908, by Vanderbilt. The dedication was on January 1, 1910.[44]

RMS Lusitania

editOn May 1, 1915,[45] Vanderbilt boarded the RMS Lusitania bound for Liverpool as a first class passenger.[46] It was a business trip, and he traveled with only his valet, Ronald Denyer, leaving his family at home in New York.

On May 7, off the coast of County Cork, Ireland, German U-boat, U-20 torpedoed the ship, triggering a secondary explosion that sank the giant ocean liner within 18 minutes. Vanderbilt and Denyer helped others into lifeboats, and then Vanderbilt gave his lifejacket to save a female passenger. Vanderbilt had promised the young mother of a small baby that he would locate an extra lifevest for her.[47] Failing to do so, he offered her his own life vest, which he proceeded to tie on to her himself, since she was holding her infant child in her arms at the time. Many considered his actions especially noble since he could not swim and he knew there were no other lifevests or lifeboats available. Because of his fame, several people on the Lusitania who survived the tragedy were observing him while events unfolded at the time, and so they took note of his actions. He and Denyer were among the 1,199 passengers who did not survive the incident.[48] His body was never recovered.[49][50][51]

There has been some historical confusion as to which member of the Vanderbilt family was booked on the Titanic in 1912 and recent[when?] studies have determined that not Alfred Vanderbilt but his uncle George Washington Vanderbilt II was actually booked to travel on the Titanic, along with his wife Edith and daughter Cornelia.[citation needed]

Legacy

editA memorial was erected on the A24 London to Worthing Road in Holmwood, just south of Dorking. The inscription reads, "In Memory of Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, a gallant gentleman and a fine sportsman who perished in the Lusitania May 7th 1915. This stone is erected on his favorite road by a few of his British coaching friends and admirers".

A memorial fountain to Vanderbilt is in Vanderbilt Park on Broadway in Newport, Rhode Island, where many members of the Vanderbilt family spent their summers. The memorial reads: "To the Memory of Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, who perished on the S.S. Lusitania in the Thirty-eighth year of his age May 7, 1915. Erected by fifty of his friends."

Children

editBy Elsie French Vanderbilt:

- William Henry Vanderbilt III, Governor of Rhode Island and business executive.

By Margaret E. McKim Vanderbilt

- Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt Jr., naval officer, Silver Star recipient, horse breeder and President of Belmont Park.

- George Washington Vanderbilt III, naval officer, explorer and scientist.

Bibliography

edit- ^ a b c "Vanderbilt Left His Wife at Home; | Wealthiest Youth in America Expected to Make Only a Short Stay Abroad. | Best Known as Horseman | Inherited $100,000,000 and Married Mrs. Smith Hollins McKim When Ellen French Divorced Him". The New York Times. 8 May 1915. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ a b c Homans, James E., ed. (1918). . The Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: The Press Association Compilers, Inc.

- ^ a b c d "Vanderbilt Engagement; Miss Elsie French to Become Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt's Wife. A Match Approved by the Late Cornelius Vanderbilt – Young People Long in Love". The New York Times. 29 April 1900. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Vanderbilt Hotel Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine from New York City Heritage Preservation Center

- ^ Vanderbilt, Arthur T. II (1989). Fortune's Children: The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt. New York: Morrow. ISBN 0-688-07279-8.

- ^ "Vanderbilt–French Wedding; To Take Place at Newport the First Week in January". The New York Times. 20 September 1900. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Alfred G. Vanderbilt Marries Miss French; St, John's Church, Newport, Exquisitely Decorated. "Harbourview", Where Reception and Wedding Breakfast Are Given, a Gorgeous Floral Bower". The New York Times. 15 January 1901. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Blair, William G. (April 16, 1981). "William H. Vanderbilt, 79, Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

William Henry Vanderbilt, a former Governor of Rhode Island who was a great-great-grandson of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, the 19th century railroad magnate, died Tuesday night at his home in South Williamstown, Massachusetts He was 79 years old. Mr. Vanderbilt, a Republican, served in the State Senate from 1928 to ...

- ^ "Died". Time. April 27, 1981. Archived from the original on October 15, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

William Henry Vanderbilt, 79, farmer-philanthropist and sometime politician who served as Governor of Rhode Island from 1938 to 1940 and was the great-great-grandson of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, the 19th century railroad magnate; of cancer; in Williamstown, Massachusetts

- ^ a b "Mrs. A.G. Vanderbilt Moves to Tuxedo; Ships Household Effects, Dogs, and Little Son's Toys from Newport. Oakland Farm Closed Mr. Vanderbilt Will Spend Summer in London, Driving the Coach Venture Between That City and Brighton". The New York Times. 25 March 1908. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Vanderbilt to Defend Suit; Details of Wife's Complaint In Divorce Action Kept Secret. Mrs. Fish Entertains for the Bryoes. Garden Sale in Aid of Hartley House". The New York Times. 3 April 1908. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "2 Witnesses Heard in Vanderbilt Suit; Valet of Alfred G. and a Woman, Supposedly His Wife's Maid, Testify in Secret. Wife the Next Witness The Greatest Reticence Observed In Divorce Action Following the Hiding of Papers In Court". The New York Times. 4 April 1908. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Decree of Divorce for Mrs. Vanderbilt; Gets Custody of Her Son and Right to Remarry, Which Is Denied to Alfred G. Vanderbilt. Mme. Ruiz's Name in Case Nothing In the Papers Referring to Alimony or Any Financial Arrangement". The New York Times. 26 May 1908. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "SOCIAL WAR AT NEWPORT.; Vanderbilt Divorce Splits the Colony Into Factions". The New York Times. 25 July 1908. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ a b c Times, Special Cable To The New York (11 June 1909). "MRS. ANTONIO RUIZ A SUICIDE IN LONDON; Was Mentioned in Connection with the Divorce Case of Alfred G. Vanderbilt. News of Death Suppressed; Had Been Rumored Here, but Not Confirmed – Inquest Held Three Weeks Ago – Divorced Last Summer". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Times, Special Cable To The New York (15 June 1909). "Ruiz Case Brought Before Parliament; Member for Jarrow Gives Notice That He Will Question Home Secretary Gladstone. Aimed at Coroner's Acts Refusal to Show Depositions Cited -Good Faith Not Questioned, but Other Court Officers Under Suspicion". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Times, Special Cable To The New York (24 April 1911). "A.G. Vanderbilt Leaves; Returns to London, While Mrs. McKim Departs for Berlin". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "No Surprise For Newport; Alfred G. Vanderbilt and Mrs. McKim's Marriage Was Expected". The New York Times. 19 December 1911. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Times, Special Cable To The New York (19 December 1911). "Vanderbilt Kept Wedding Guarded; His Marriage to Mrs. McKim Secretly Planned – Only the Four Witnesses Present". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ a b "Mrs. Emerson, 75, of the '400' Dead; Society Leader Was Mother of Alfred Vanderbilt – Her Father Headed Drug Firm". The New York Times. January 3, 1960. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Times, Special Cable To The New York (18 December 1911). "A.G. Vanderbilt Weds Mrs. M'kim; Quiet Sunday Marriage in a Registrar's Office in an English Village". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "McKim – Emerson". The New York Times. 31 December 1902. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Dr. Smith H. M'kim Dies in Baltimore; Member of One of Oldest Families There and Former Resident of This City". The New York Times. 21 September 1932. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Dr. Smith H. M'kim And Wife Separate; Left Their Apartments at the Plaza Recently, and Mrs. McKim Went to Paris. No Divorce, Say Fam1ly; Separation Said to Have Been Arranged Amicably – Mrs. McKim a Daughter of I.E. Emerson". The New York Times. 22 May 1909. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Mrs. M'kim Wins Divorce at Reno; Tells Her Story in Court, Accusing Dr. McKim of Cruelty, Non-Support, and Drunkenness. Left Him Two Years Ago Declares Her Father, the Baltimore Drug Manufacturer, Had Supported Them – No Answer Is Filed". The New York Times. 14 August 1910. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Mrs. A.G. Vanderbilt Gives Birth To Son; Former Mr. McKim Has Been Living in England Since Second Marriage". The New York Times. 23 September 1912. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Another $5,000,000 For A. G. Vanderbilt; He Gets Second Quarter of His Inheritance on 25th Birthday—Buys 450-Acre Farm". The New York Times. 23 September 1937. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "George Vanderbilt Is Killed in Plunge; George Vanderbilt, 47, Is Killed In Plunge From Hotel on Coast". The New York Times. June 25, 1961. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ Gloria Baker later married Henry J. Topping Jr.

- ^ Speers, L. C. (30 January 1927). "Damage Bills of American Citizens Reaching $1,479,000,000 Have Been Reduced To About $180,000,000 – Vanderbilt and Frohman Estates Get Nothing". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Hoyt, Edwin P. (1962). The Vanderbilts and Their Fortunes. Garden City, New York: Double Day & Company Inc. p. 364. hdl:2027/wu.89067937748.

- ^ a b Tulsa Daily Legal News. (10 August 1917). Value of New York Estate of Alfred G. Vanderbilt Snr. (d. 1915). Newspapers.com. Retrieved 7 April 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/tulsa-daily-legal-news-value-of-new-york/144925245/

- ^ The Tacoma Daily Ledger. (9 August 1917). Alfred G Vanderbilt – Division of Estate. Newspapers.com. Retrieved 7 April 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-tacoma-daily-ledger-alfred-g-vanderb/144925447/

- ^ "Docket No. 2187: Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt". Claims commission. 17 June 2011.

- ^ "Court Holds Lusitania Sinking Act of War And Alfred G. Vanderbilt Insurance Void". The New York Times. 31 January 1923. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Shepperd, Ronald (1982). The Manor of Wistomble in the Parish of Mickleham. Westhumble Association. p. 70. ASIN B000X8PZMC.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Shepperd, Ronald (1991). Micklam the story of a parish. Mickleham Publications. p. 156. ISBN 0-9518305-0-3.

- ^ Moore, Charles Jeffers (1992). "Treatment of an Early 20th Century Road Coach: Alfred G. Vanderbilt's "Venture"" (PDF). Wooden Artifacts Group of the American Institute for Conservation.

- ^ Cunningham, Bill (August 26, 2012). "On the Street; Pomp". The New York Times.

- ^ Kintrea, Frank (October 1967). "When The Coachman Was A Millionare". American Heritage. Vol. 18, no. 6.

- ^ deed of transfer

- ^ "Vanderbilt Children Hurt; Tree Falis in Front of Their Auto and Driver Is Killed". The New York Times. 3 August 1917. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Sagamore Lodge". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ "Young Men's Christian Association (Y.M.C.A), Vanderbilt Hall (1908) (Newport, Rhode Island)". Wilimapia. Open Publishing. Retrieved 2022-03-08.

- ^ "OFF FOR EUROPE TODAY. | Some of the Passengers on Five Steamships=The Arrivals". The New York Times. 1 May 1915. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "The Day at Queenstown.; How Vanderbilt and Others Died". The New York Times. 10 May 1915. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Preston, Diane (May 2002). "Torpedoed! The Sinking of the Lusitania". Smithsonian Magazine. pp. 64–65. Archived from the original on 2006-09-01.

- ^ "Vanderbilt's Body is Reported Found; Secretary in Queenstown Investigating Persistent Rumors Current There". The New York Times. 12 May 1915. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Vanderbilt Search Abandoned". The New York Times. 11 May 1915. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Vanderbilt Prayer is 'Burial At Sea'; The Only Mention of Lusitania Tragedy in Memorial at Home of A. G.'s Mother. Chapel in Vaulted Hall; 200 Relatives and Friends Hear Impressive Episcopal Service Read – Choir Sings Hymns". The New York Times. 28 May 1915. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Times, Special Cable To The New York (11 June 1915). "Vanderbilt's Body Not Recovered; Lusitania Victim Washed Up on the Irish Coast Believed to Have Been a Russian". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2017.