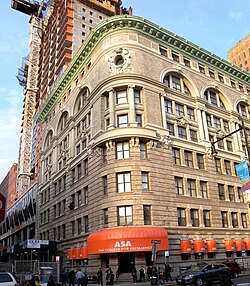

81 Willoughby Street (formerly the New York and New Jersey Telephone and Telegraph Building) is a commercial building in the Downtown Brooklyn neighborhood of New York City. Built from 1896 to 1898 as the headquarters for the New York and New Jersey Telephone and Telegraph Company (later the New York Telephone Company), it is located at the northeast corner of Willoughby and Lawrence Streets. The building is eight stories tall and was designed by Rudolphe L. Daus in a mixture of the Beaux-Arts and Renaissance Revival styles.

| 81 Willoughby Street | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Alternative names | New York and New Jersey Telephone and Telegraph Building |

| General information | |

| Type | Commercial |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts and Renaissance Revival |

| Location | 81 Willoughby Street, Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°41′32″N 73°59′10″W / 40.6923°N 73.9861°W |

| Construction started | 1896 |

| Completed | 1898 |

| Owner | 81 Willoughby LLC[1] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 8 |

| Floor area | 73,860 sq ft (6,862 m2)[1] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Rudolphe L. Daus |

| Designated | June 29, 2004 |

| Reference no. | 2156[2] |

The facade is largely clad with limestone on its bottom four stories, as well as brick and terracotta on its top four stories. The Willoughby and Lawrence Street elevations are each divided vertically into three bays and are highly similar in design. The main entrance is through an ornamental arch on Willoughby Street, at the southeast corner of the building. The remainder of the building contains ornamental details such as a curved corner with an oculus window, as well as a deep cornice on the upper stories. The building measures eight stories high with a basement and was largely constructed with a steel frame. When the building was constructed, the entire structure contained various departments, with a telephone exchange on the top floor.

The New York and New Jersey Telephone Company constructed 81 Willoughby Street in 1896 in response to increased business. Plans for the new structure were filed in May 1896, and the building was occupied by early 1898. The company's business grew so rapidly that it moved some operations to another building in 1904 and constructed a six-story annex at 360 Bridge Street between 1922 and 1923. New York Telephone acquired 81 Willoughby Street in 1929 and retained central office equipment there after a new telephone building opened in 1931 at 101 Willoughby Street. In 1943, the company sold off the building, which has remained a commercial structure ever since, accommodating offices, laboratories, and educational institutions. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the building as a city landmark in 2004.

Site

edit81 Willoughby Street is in the Downtown Brooklyn neighborhood of New York City.[3] It occupies a rectangular land lot on the northeastern corner of Lawrence and Willoughby Streets,[1][3] with an alternate address of 119–127 Lawrence Street.[2] The site has frontage of 100 feet (30 m) on Lawrence Street to the west and 107.5 ft (32.8 m) on Willoughby Street to the south,[4][5] with an area of 10,749 sq ft (998.6 m2).[1] Nearby buildings include the Brooklyner and Brooklyn Commons (formerly MetroTech) to the north; the BellTel Lofts (101 Willoughby Street) and Duffield Street Houses to the east; 388 Bridge Street and AVA DoBro to the southeast; and 370 Jay Street and the Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters to the west.[1] In addition, entrances to the New York City Subway's Jay Street–MetroTech station, served by the A, C, F, <F>, and R trains, are just outside the building.[6]

The site was formerly occupied by a stable on Lawrence Street and four houses on Willoughby Street.[4] Before the New York and New Jersey Telephone Company Building was developed at 81 Willoughby Street, the adjacent section of Willoughby Street had largely contained houses. By the 1890s, many of these houses were replaced by commercial buildings.[5]

Architecture

editRudolphe L. Daus designed 81 Willoughby Street.[2][7][8] The AIA Guide to New York City describes the structure as being in a mixture of the Beaux-Arts and Renaissance Revival styles,[7] but a contemporary publication from 1897 characterized the building as being solely of Italian Renaissance design.[9] The building is eight stories, with a curved corner to its southwest.[10][11]

Facade

editThe facade is largely clad with tan brick and limestone and is ornamented with terracotta.[10] Limestone was used on the lowest stories, while brick and terracotta were used above.[9][12] The southern and western elevations of the facade, which respectively face Willoughby and Lawrence Street, are each divided vertically into three bays and are highly similar in design.[10] At the easternmost section of the Willoughby Street elevation is an additional, narrow bay without ornament and clad almost entirely in brick.[13] A curved corner connects the western and southern elevations. The building has stone cornices above the first, fourth, and sixth stories and a copper cornice above the eighth story. The windows all consist of one-over-one sash windows with aluminum frames.[10] There are telephone-related motifs on the curved corner.[11] The juxtaposition of plain facade materials was intended to emphasize the building's ornamentation, while the cornice and the oculus at the corner were intended to draw attention to the building from the intersection of Willoughby and Lawrence Streets.[10]

Ground story

editOn Willoughby Street, the easternmost bay contains the building's main entrance, a double-height arch with an entablature above. Recessed beneath the center of the archway is a rectangular door frame with molded earpieces, receivers, wires, and other telephone-related motifs.[10][14] Immediately above this door frame, an entablature runs horizontally across the archway; this is topped by a triangular pediment. The second story of the archway is filled with windows. The archway itself has a coffered ceiling, supported by two columns on either side of the doorway; these columns contain capitals in the Corinthian order. The top of the arch has a keystone. There is a double-height pier on either side of the archway, which has more moldings of telephone-related motifs. These piers support the entablature, which contains the words "Telephone Building". Above the piers, on the third story, are medallions with eagles.[10]

A recessed service entrance is located within the easternmost, narrow bay to the right of the main entrance. The remainder of the facade is clad with rusticated, cement-coated limestone blocks. The center bay on Lawrence Street has another service entrance, placed within an arch that has largely been infilled with cement; this entrance is reached by metal steps. The corner of Lawrence and Willoughby Streets contains a stoop with metal balustrades, ascending to a glass door. All the other openings on the ground story consist of windows with awnings above them. A stone-and-brick cornice runs horizontally above the ground story.[10]

Upper stories

editOn the second to fourth stories, the facade is clad in brick and contains grooves at regular intervals, which give it a rusticated look. There are three windows per floor in each of the three main bays on Lawrence and Willoughby Streets, as well as on the curved corner. Each of the windows is rectangular, with a stone window sill below and a flat lintel above.[10] The easternmost bay on Willoughby Street contains one window per floor. A protruding cornice runs above the facade on the fourth story, continuing onto the narrow Willoughby Street bay.[13] There are medallions below the cornice between each of the bays on Lawrence and Willoughby Streets, as well as brackets below the cornice along the curved corner.[10]

On the fifth and sixth stories, a pair of engaged columns flanks each of the three primary bays on Lawrence and Willoughby Streets. Within each bay, the central fifth-story window is flanked by colonettes that hold up triangular pediments.[10] Another cornice runs above the sixth story; this cornice protrudes from the facade, except within each bay, where it is recessed between the windows above and below.[13] At the seventh story, the curved corner has an oculus with terracotta decorations and cresting.[8][14][15] The primary bays contain arched windows, which are divided vertically into three panes; a keystone tops the center pane, and the entire arch contains ornate moldings. On the eighth story, each of the primary bays has three windows, which are separated by short pilasters.[15] A copper cornice runs above the eighth story, protruding from the facade.[8][15] Above the cornice was a short penthouse (not visible from the street), which had restrooms and dining rooms.[5]

Interior

editThe building measures eight stories high with a basement.[5][9] The structure is largely constructed with a steel frame, although the foundations are composed of concrete walls measuring 4 to 5 ft (1.2 to 1.5 m) thick. These concrete walls support a grillage from which the beams in the superstructure ascend. The floor slabs are made of hollow brick flat arches and "Columbian fireproof" slabs.[9][12] The building contained a ventilation shaft that rose 25 ft (7.6 m) above the roof. Air was drawn down the shaft to the basement, passing through several filters, and then was supplied to the offices inside the building via fans and ducts. A separate system of exhaust ducts ventilated the air onto the roof.[9] A set of pipes also carried hundreds of telephone and telegraph cables from the cellar to the telephone switchboards on the top floor.[16]

When the building was constructed, the basement and first four floors were dedicated to various New York and New Jersey Telephone Company departments.[5] The first floor contained the supply department, the second floor contained the repair shop, and the fourth floor contained the general superintendent's office.[12] The fifth floor contained the offices of the general manager and vice president, the sixth floor contained the treasurer's office, and the seventh floor contained the offices of the auditors' department.[5][12] The eighth floor originally housed the New York and New Jersey Telephone Company's primary Brooklyn exchange and could accommodate 5,000 to 6,000 subscribers when the building opened.[5] This story contained the offices of the "hello girls", the company's mostly female telephone operators.[12]

History

editThe Bell Telephone Company was established in 1877 and merged with the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company in 1879 to form the National Bell Telephone Company.[17] One of the subsidiaries of the combined firm was the New York and New Jersey Telephone Company, which was created in 1883.[14][18] Originally, the New York and New Jersey Telephone Company operated telephone exchanges in North Jersey, Staten Island, and Long Island, licensing them from National Bell.[18][19] At its inception, the company had 2,339 subscribers, most of whom lived in Brooklyn.[12][18] With the growing popularity of telephones, the number of subscribers grew to nearly 20,000 by 1897.[19]

Development

editThe New York and New Jersey Telephone Company decided in early 1896 to increase its capital stock.[20] That April, the company decided to purchase a land lot on the southwest corner of Willoughby and Bridge Streets, just to the southeast of the site at 81 Willoughby Street.[20] Local media reported shortly afterward that the company had agreed to acquire the northeast corner of Lawrence and Willoughby Streets, on which the company's central office would be constructed.[21][22] Rudolphe Daus created preliminary sketches for a ten-story, stone-and-brick building in May 1896.[4] At the time, the building was planned to cost between $250,000 and $275,000.[4][23] Work on the structure was slightly delayed because of difficulties in acquiring a portion of the site.[24]

Excavations were underway by March 1897, when the building had been downsized to eight and a half stories.[5] When the contractors began installing plumbing in the building that August, they hired plumbers affiliated with a labor union in the then-separate city of New York, prompting workers affiliated with the Brooklyn union to go on strike.[25] Union-affiliated roofers, tin workers, and sheet iron workers also went on strike in September to advocate wage increases for the workers who were installing the building's cornices and skylights.[26] When these union workers went on strike again the next month, the workers' bosses decided to complete the cornices and skylights themselves.[27][28] The building was completed by February 1898,[12] and the company's main telephone exchange opened at the building in November 1899.[16][29]

Use as telephone office

editThe New York and New Jersey Telephone Company's business grew so rapidly that, by 1903, the company had decided to move some of its operations to a new building at Atlantic Avenue and Clinton Avenue.[30] The Atlantic Avenue building was completed in March 1904.[31] All of the trunk lines from Nassau and Suffolk counties were moved from 81 Willoughby Street to the Atlantic Avenue building, as were the storerooms, repair shops, and supply rooms.[30] The New York and New Jersey Telephone Company opened a training center for telephone operators on the top story in 1905 and installed equipment in the training center the next year.[32] 81 Willoughby Street served as the general business office for subscribers in western and southern Brooklyn by 1908.[33] New York and New Jersey Telephone and five other companies were merged in 1909, becoming the New York Telephone Company,[18][34] which continued to operate from 81 Willoughby Street.[35] The building also contained other tenants, such as a company selling security alarms.[36]

The New York Telephone Company filed construction plans in November 1920 for an eight-story annex between Bridge and Lawrence Streets.[37] The company began constructing a six-story annex at the northwest corner of Willoughby and Bridge Streets in April 1922. The annex, extending 107 ft (33 m) along Willoughby Street and 250 ft (76 m) along Bridge Street, was to cost $1.25 million.[38][39] Although the annex was structurally separate from the original building, it would be connected to the original structure at every story, and the two lobbies were to be connected by a ground-story arcade. The annex was designed so it could be expanded to 12 stories if needed.[39] A central office for emergency fire alarms was established within the building in 1921, allowing operators to transmit fire alarms during emergencies.[40] The annex's construction required the demolition of nine existing structures, which had been razed by September 1922.[41] The annex at 360 Bridge Street was completed in October 1923 at a cost of $1.5 million; it housed three central office departments that could not be accommodated in the old building.[42]

During 1923, New York Telephone hired Western Electric to install one manually-operated and one machine-operated central office at 81 Willoughby Street.[43] The company allocated money in 1927 for the creation of a dispatching bureau and a central testing bureau within the annex.[44][45] The same year, New York Telephone relocated its Long Island headquarters to the building from Manhattan.[46] New York Telephone, which had long rented 81 Willoughby Street, formally acquired the structure in 1929.[10] The New York Telephone Company announced in late 1929 that it would relocate 3,500 employees from various buildings, including 81 Willoughby Street,[47][48] into a new structure designed by Ralph Walker at 101 Willoughby Street.[49][50] A central office for dial telephones was installed at 81 Willoughby Street and 360 Bridge Street in early 1931.[51][52] After 101 Willoughby Street was completed in October 1931,[53] the company continued to use the older structures to accommodate central office equipment.[54][55]

Subsequent use

editThe New York Telephone Company sold the building, which at the time housed the Sperry Gyroscope Corporation, to an investor from Manhattan in August 1943.[56] Poly Tech's Institute of Polymer Research moved to 81 Willoughby Street in late 1946, operating five laboratories there.[57] The same year, the Sperry Gyroscope Company moved its training school to the building, occupying the second floor;[58] the space could accommodate 80 daily students.[59] By the early 1950s, Poly Tech's polymer institute occupied three of 81 Willoughby Street's eight floors, and the institute had 520 graduate-level students, including 120 full-time students.[60] The New York state government also opened a rent-collection office within the building in 1956, replacing an earlier rent office on Fulton Street.[61] Over the years, 101 Willoughby Street was sold several times and contained medical offices and a school.[10] Meanwhile, New York Telephone Company and its successor NYNEX retained ownership of the annex at 360 Bridge Street.[50]

Lebanese-American businessman Albert Srour bought 81 Willoughby Street in 1990 and cleaned the building's cornice and facade, as well as replaced the elevator.[14] The Municipal Art Society's Preservation Committee, along with local civic group Brooklyn Heights Association, began petitioning the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) to designate over two dozen buildings in Downtown Brooklyn as landmarks in 2003.[62] The LPC designated 81 Willoughby Street as a landmark in June 2004,[63] along with New York Telephone's later building at 101 Willoughby Street later the same year.[14] The buildings were designated shortly after the city government had approved a development plan for Downtown Brooklyn. The New York Times wrote that 81 Willoughby Street's landmark designation "is only the beginning of a potential wave" of landmarks in the neighborhood.[64]

After the landmark designations, 81 Willoughby Street continued to be used as offices. The New York Times described the building as being occupied by nonprofit organizations, as well as doctors' and dentists' offices.[14] By the late 2000s, ASA College occupied the ground floor and had mounted a canopy outside the building;[14] the college was shuttered in 2023.[65] Discount store Dollar Jackpot leased about 10,000 sq ft (930 m2) on the building's ground floor in 2021.[66] In addition, NY Beauty Suites opened a coworking space for beauty salon operators in early 2022.[67] The coworking space contained 20 suites,[68] each of which spanned between 100 and 200 sq ft (9.3 and 18.6 m2).[67]

Critical reception

editChristopher Gray of The New York Times referred to the building in 2008 as "a robust structure dominated by six great three-story arches", which nonetheless had "delicate and inventive" decoration.[14] According to Gray, the two telephone buildings at 81 and 101 Willoughby Street were one block apart physically but "eons apart in their architecture", contrasting number 81's Beaux-Arts design with number 101's Art Deco design.[14] Francis Morrone wrote in 2001 that 101 Willoughby Street "and the earlier telephone building at the northeast corner of Lawrence Street [at 81 Willoughby Street] make Willoughby one of the most exciting streets in downtown Brooklyn".[69] The historian Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel wrote in 2011 that the building "served as a major statement of [New York and New Jersey Telephone]'s expansion in the area, providing offices and telephone switching in the heart of Brooklyn's expanding business district".[8]

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d e "81 Willoughby Street, 11201". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on June 12, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2004, p. 1.

- ^ a b White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 587. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d "New Telephone Building". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 7, 1896. p. 14. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "A New Building". The Standard Union. March 12, 1897. p. 6. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Jay St-MetroTech (R)". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ a b White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 586. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Barbaralee (2011). The Landmarks of New York (5th ed.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-4384-3769-9.

- ^ a b c d e "New York and New Jersey Telephone Building, Brooklyn, N. Y. Mr. R. L. Daus, Architect, Brooklyn, N. Y.". The American Architect and Building News. Vol. 57, no. 1124. July 10, 1897. p. 19. ProQuest 124634488.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Landmarks Preservation Commission 2004, p. 4.

- ^ a b U.S. Brooklyn Court Project: Environmental Impact Statement. U.S. General Services Administration. 1996. p. III.C5. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "A Magnificent Structure That Is Nearing Completion". Times Union. February 26, 1898. p. 13. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2004, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gray, Christopher (March 30, 2008). "One Owner, Two Markedly Different Designs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2004, p. 5.

- ^ a b New York Review of the Telegraph and Telephone and Electrical Journal. McGraw-Hill Publishing Company. 1899. pp. 275–276. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2004, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 2004, p. 3.

- ^ a b "Our Telephone System". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 2, 1898. p. 32. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "New Telephone Building". The Standard Union. April 11, 1896. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "New Telephone Building". The Standard Union. April 15, 1896. p. 2. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "Telephone Company's New Building". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 15, 1896. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "Building Intelligence.: Advance Rumors. Apartment-houses. Churches. Educational. Factories. Houses. Office-buildings. Stores. Tenement-houses. Warehouses. Miscellaneous". The American Architect and Building News. Vol. 52, no. 1065. May 23, 1896. p. XV. ProQuest 124621545.

- ^ "Local Outlook". The Standard Union. June 6, 1896. p. 3. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "Fight Kept Up". The Standard Union. August 24, 1897. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "A Big Strike". The Standard Union. September 21, 1897. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "O'Brien Charges Fraud; Says Contract for Brooklyn Anchorage Was Wrongfully Awarded". The New York Times. October 7, 1897. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "Union Resents". The Standard Union. October 5, 1897. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "Phone Center 50 Years on Willoughby St". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 11, 1949. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "Telephone Exchange for Long Island Business". Times Union. May 20, 1903. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Activity in the Realty Market Evidences the Return of Spring". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 19, 1904. p. 17. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Unique School for Telephone Operators Where 'Hello Girls' Are Trained". The Standard Union. November 18, 1906. p. 15. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Telephone Co. Merges Various Departments". The Brooklyn Citizen. April 29, 1908. p. 4. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "New York Telephone Co. Sale". The Wall Street Journal. September 17, 1909. p. 2. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "New York 'Phone Co. in Complete Control". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 25, 1909. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Burglar Alarm Firm in Larger Quarters". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 27, 1940. p. 18. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ "$1,050,000 Extension". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 28, 1920. p. 59. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Plan Brooklyn Addition; New York Telephone Company's Building Will Cost $1,250,000". The New York Times. April 30, 1922. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "$1,250,000 Addition to Telephone Building". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 20, 1922. p. 14. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Use Phone for Fire Alarms". The Brooklyn Citizen. July 16, 1921. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Boro's Business Growth Reflected in Buildings Under Way". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 17, 1922. p. 97. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Over $5,000,000 Involved in Boro Office Buildings and Theater Under Way". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 21, 1923. p. 39. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "New York Telephone". The Wall Street Journal. September 14, 1923. p. 3. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 130064172.

- ^ "Vote Telephone Extension; Directors of New York Company to Spend $9,153,220". The New York Times. January 29, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 25, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "N. Y. Telephone Co. Plans $9,153,220 New Construction: Board of Directors Devotes $8,309,630 of Total to Metropolitan Area; New Unit in East 13th Street". New York Herald Tribune. January 29, 1927. p. 19. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113514807.

- ^ "Long Island Phone Headquarters Here". The Standard Union. August 5, 1927. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Telephone Company Plans Skyscraper For Brooklyn: 23-Story Building to Cost $4,500,000 Will Be Erected on Willoughby Street". New York Herald Tribune. September 5, 1929. p. 41. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1111738760.

- ^ "Phone Company Plans 23-story Headquarters". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 4, 1929. p. 5. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "27-Story Building to Rise in Brooklyn; Phone Company Lets Contract for Structure at Willoughby and Bridge Streets". The New York Times. November 17, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Long Island Headquarters of the New York Telephone Company (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 21, 2004. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ "Brooklyn's Oldest Phone Office Goes on Dial System Tomorrow". New York Herald Tribune. May 29, 1931. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1114186076.

- ^ "Telephone Co. Plans to Spend $7,796,480". Times Union. March 30, 1930. p. 42. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ "New York Telephone Co". The Wall Street Journal. October 29, 1931. p. 13. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 130955111.

- ^ "Telephone Centre Built; Headquarters Structure in Brooklyn Nears Completion". The New York Times. March 29, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ "L. I. Phone Headquarters Shown from Air". Times Union. October 29, 1931. p. 11. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ "Old Tel. Building on Willoughby St. Sold to Investor". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 29, 1943. p. 28. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Plastics Lab Expands Quarters". Daily News. December 26, 1946. p. 483. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ "Brooklyn Notes". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 8, 1946. p. 7. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ "Local Roundout". The Brooklyn Citizen. November 4, 1946. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ "Brooklyn Poly Marks Century With Biggest Engineer Total". Newsweek. Vol. 41, no. 11. March 16, 1953. pp. 64–67. ProQuest 1895333136.

- ^ "New Brooklyn Rent Office". The New York Times. April 8, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (February 20, 2005). "Can Nearly Half a Building Add Up to a Landmark?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ "A Beaux-Arts Beauty in Brooklyn". The New York Times. June 30, 2004. p. 4. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 432776866.

- ^ Cardwell, Diane (July 4, 2004). "In a Ragtag Hub, Look Up, For There's Beauty Above". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ Khafagy, Amir (March 2, 2023). "Troubled ASA College Closed But Left Students Out In the Cold". Documented. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ Rizzi, Nicholas (January 21, 2021). "Dollar Jackpot Takes 10K SF in Downtown Brooklyn". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "NYBeauty Suites: When One Door Closes, Another Opens". BKReader. January 25, 2022. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ Long, Ariama C. (January 6, 2022). "BKLYN Commons' Johanne Brierre". New York Amsterdam News. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ Morrone, Francis (2001). An Architectural Guidebook to Brooklyn. Gibbs Smith. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4236-1911-6. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

Sources

edit- New York and New Jersey Telephone and Telegraph Building (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 29, 2004.