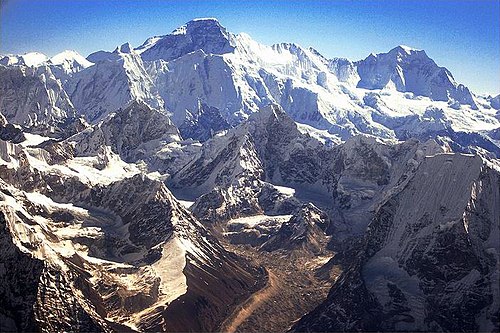

The 1952 British expedition to Cho Oyu (26,750 feet (8,150 m)) the Turquoise Goddess was organized by the Joint Himalayan Committee. It had been hoped to follow up the 1951 Everest expedition with another British attempt on Everest in 1952, but Nepal had accepted a Swiss application for 1952, to be followed in 1953 with a British attempt. So in 1952, Eric Shipton was to lead an attempt to ascend Cho Oyu, and Griffith Pugh was to trial oxygen equipment and train members for 1953. But the expedition failed both aims; that plus Shipton’s poor leadership and planning resulted in his replacement as a leader for the 1953 expedition.[1]

The expedition members were Eric Shipton, Charles Evans, Tom Bourdillon, Ray Colledge, Alfred Gregory and Griffith Pugh (UK); from NZ Ed Hillary, George Lowe and Earle Riddiford, and from Canada Campbell Secord[2] (Michael Ward was not available as he was completing his national military service and sitting a surgery examination[3]). The expedition sailed on 7 March from Southampton; except for Shipton, Pugh and Secord who flew out later.[4]

The New Zealand Alpine Club (NZAC) provided financial support, though because of sponsorship by The Times other newspaper articles could not be published until a month afterwards.[5] Riddiford ate and tented with the British members because of his dispute with Lowe in Ranikhet when he was selected for the 1951 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition instead of Lowe (who did not have the money to pay his share of the costs)[6]

Objectives and planning

editThe objectives were to ascend the summit; and to train up a pool of climbers who could acclimatise well at 24,000 feet (7,300 m) or more and to study the use of oxygen apparatus.[7][8][9]

Shipton said in his first despatch to "The Times" that his objective was to climb Cho Oyu.[1]

Eric Shipton had spent a day on lists of stores, but Earle Riddiford (who had returned from the 1951 expedition with Michael Ward and was now staying with Norman and Enid Hardie in London) had to do the ordering, packing and despatching, with Shipton often not around to consult. [10][11] The New Zealand amount of food for two people was the same as what Shipton had allowed for four people. Shipton had included little sugar, butter, jam, porridge or milk. Riddiford described the food as "bloody awful", and said that younger climbers like Bourdillion were "half starved". So food stocks were supplemented with New Zealand supplies.[12]

The expedition

editBase camp was established on 29 April 1952 at Lunak below the Nangpa La trading pass. On the trek in, Shipton acclimatised quickly, but he did not allow for others who did not.[13]

Worried about being spotted by Chinese troops across the border, Shipton was unwilling to mount a full-scale attempt from Tibet where the climbing seemed easier or to establish a base (or at least one camp) on the Tibetan side (as proposed by Hillary, Lowe, Riddiford, and Secord). Shipton had been a British consul in Kashgar and then Kunming, China until he was expelled by the new government, and wanted to avoid any clashes with Chinese troops on the Tibetan side in case they were denounced as spies, with the possibility of "derailing" the 1953 expedition. (In 2006 there was a shooting incident involving Chinese troops near Nangpa La). But after a "demoralising" afternoon arguing against a camp on the Tibetan side Shipton agreed to a camp just short of the Nangpa La, and to send a party to attempt the first crossing of the Nup La pass to the east of Cho Oyo, which could be quickly withdrawn if Chinese soldiers were sighted. [14] The exploratory party was led by Ed Hillary, but was hampered by a dangerous ice cliff and a stretched supply chain, which had to turn back at 22,400 feet (6,800 m). Hillary later said he felt "almost a sense of shame that we'd allowed ourselves to admit defeat so easily".[15][16]

Hillary and Lowe with three "very nervous" sherpas (Ang Puta, Tashi Puta and Angye) had crossed the Nup La col, so made the first crossings of the three cols between the Khumba and the Barun Valley. "We attempted the heavily crevassed head of the Ngojumba Glacier and forced away up the narrow Nup La Pass". Hillary and Lowe "like a couple of naughty schoolboys" went deep into Chinese territory, down to Rongbuk, and round to the old prewar Camp III beneath the North Col. [17] Crossing the icefalls took six days to cover 6.5 kilometres (4.0 mi) but were said Lowe "the most exciting, exacting and satisfying mountaineering that we had undertaken" and done "with less than I would have had for a weekend tramp in New Zealand" Going into the Barun Glacier between Everest and Makalu and seeing Tibet from the head completed a circuit of Everest over its highest passes. [18]

At the end of the expedition in June, Shipton went off with Evans, Hillary and Lowe through the jungles of Nepal and to the Indian border along the banks of the Arun River. They climbed eleven mountains in the Barun to the west of Nangpa La.[19] Hillary and Lowe "rafted" down the Arun River on two air-mattresses joined together; just avoiding a massive whirlpool and cateract by hanging onto a rock and then to a rescue rope lowered by Shipton.[20]

Oxygen

editGriffith Pugh the expedition physiologist, was preparing for this role again in 1953. His formal recommendations to the Himalayan Committee included: fitness and team spirit essential; oxygen equipment necessary above South Col; closed-circuit oxygen favoured; clothing to be individually tailored; general and food hygiene important; climbers must acclimatise above 15,000 feet (4,600 m) for at least 36 days; and poor acclimatisation should not lead to rejection, as the cause could be temporary illness.[21] But his experiments were "stymied" as no-one reached 24,000 feet (7,300 m).[1]

Pugh was critical of poor hygiene around the camps and the drinking of contaminated water, with sickness on the approach trek.[22]

According to Pugh and Wood in 1953, the principal findings from experiments carried out on Menlung La at 20,000 feet (6,100 m) in 1952 were:

- The more oxygen breathed the greater the subjective benefit

- The weight to a large extent offset increased performance

- The minimum required was a flow rate of 4 litres/minute; prewar 1, 2 or 2.25 litres/minute had been used

- There was a great reduction in pulmonary ventilation

- There was a great relief in the feeling of heaviness and fatigue in the legs (although it was not tested whether endurance was improved).

Bourdillon decided that the best combination was a closed-circuit apparatus breathing pure oxygen for climbing and an open-circuit set giving a comparatively low concentration of oxygen for sleeping. With his father, Robert Bourdillon, he developed the closed-circuit oxygen apparatus used by Charles Evans and himself on their pioneering climb to the South Summit of Everest on 26 May 1953.[23]

Aftermath

editThe expedition did not achieve either objective, and Shipton’s reputation was "very publicly blown to smithereens" in Britain, with the expedition "one of the great black holes in the history of postwar mountaineering" Chapter 11 is titled "A frightfully British bungle". [24]

Shipton did not face the Committee in London until 28 July because of the end trip. He was replaced as leader in 1953 by John Hunt.[25]

Shipton and Hillary only briefly mention the expedition in their memoirs. Several members thought Shipton an unsuitable "big party" leader for 1953: Pugh, Riddiford, Secord;[26] and also Hillary privately in his diary although he was "guarded" in public comments.[27]

On October 19, 1954, a small Austrian expedition led by Herbert Tichy - with the Tyrolean Sepp Jöchler and the Sherpa Pasang Dawa Lama - succeeded in climbing the mountain for the first time, without additional oxygen and with only very few equipment (960 kg).[28]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c McKinnon 2016, p. 147.

- ^ Evans, R.C. (1953). "The Cho Oyu Expedition 1952" (PDF). Alpine Journal. #59: 9–18. ISSN 0065-6569. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ Gill 2017, p. 158.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, p. 309.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, p. 122.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, p. 145.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, p. 137.

- ^ Hunt 1953, p. 22.

- ^ Gill 2017, pp. 160, 161.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, p. 138.

- ^ Gill 2017, pp. 161, 162.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, pp. 123, 147.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, p. 141.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, pp. 142, 143.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 267–268.

- ^ Lowe & Lewis-Jones 2013, p. 59.

- ^ Lowe & Lewis-Jones 2013, pp. 23, 65, 212.

- ^ Lowe & Lewis-Jones 2013, pp. 59, 65, 67.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, pp. 146, 147, 151, 164.

- ^ Lowe & Lewis-Jones 2013, pp. 164, 212.

- ^ Unsworth (1981), pp. 297–298.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, pp. 138, 141.

- ^ Hunt 1953, pp. 257–262, 277.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, pp. 137, 149.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, p. 151.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, pp. 133, 143, 149.

- ^ McKinnon 2016, pp. 150, 154.

- ^ Herbert Tichy: Cho Oyu, Vienna 1955.

Sources

edit- Gill, Michael (2017). Edmund Hillary: A Biography. Nelson, NZ: Potton & Burton. pp. 158–167. ISBN 978-0-947503-38-3.

- Hunt, John (1953). The Ascent of Everest. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Isserman, Maurice; Weaver, Stewart (2008). Fallen Giants : A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes (1 ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300115017.

- Lowe, George; Lewis-Jones, Huw (2013). The Conquest of Everest: Original Photographs from the Legendary First Ascent. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-54423-5.

- McKinnon, Lyn (2016). Only Two for Everest. Dunedin: Otago University Press. ISBN 978-1-972322-40-6.

- Unsworth, Walt (1981). Everest. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0713911085.

External links

edit- McKinnon, Lyn (2016). Only Two for Everest. Dunedin: Otago University Press. ISBN 978-1-972322-40-6. (includes cover photo; from left: Lowe, Riddiford, Hillary; Cotter (seated))