The Exposition Universelle of 1900 (French pronunciation: [ɛkspozisjɔ̃ ynivɛʁsɛl]), better known in English as the 1900 Paris Exposition, was a world's fair held in Paris, France, from 14 April to 12 November 1900, to celebrate the achievements of the past century and to accelerate development into the next. It was the sixth of ten major expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937.[a] It was held at the esplanade of Les Invalides, the Champ de Mars, the Trocadéro and at the banks of the Seine between them, with an additional section in the Bois de Vincennes, and it was visited by more than fifty million people. Many international congresses and other events were held within the framework of the exposition, including the 1900 Summer Olympics.

| 1900 Paris | |

|---|---|

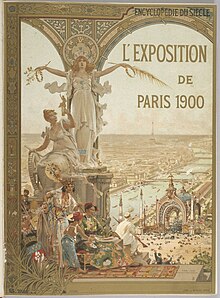

Poster | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | International Recognized Exhibition |

| Name | L'Exposition de Paris 1900 |

| Area | 216 hectares (530 acres) |

| Visitors | 48,130,300 |

| Participant(s) | |

| Business | 76,112 |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| City | Paris |

| Venue | Esplanade des Invalides, Champ de Mars, Trocadéro, banks of the Seine and Bois de Vincennes |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | 14 April 1900 |

| Closure | 12 November 1900 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Brussels International (1897) in Brussels |

| Next | Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis |

Many technological innovations were displayed at the Fair, including the Grande Roue de Paris ferris wheel, the Rue de l'Avenir moving sidewalk, the first ever regular passenger trolleybus line, escalators, diesel engines, electric cars, dry cell batteries, electric fire engines, talking films, the telegraphone (the first magnetic audio recorder), the galalith and the matryoshka dolls. It also brought international attention to the Art Nouveau style. Additionally, it showcased France as a major colonial power through numerous pavilions built on the hill of the Trocadéro Palace.

Major structures built for the exposition include the Grand Palais, the Petit Palais, the Pont Alexandre III, the Gare d'Orsay railroad station and the Paris Métro Line 1 with its entrances by Hector Guimard; all of them remaining today, including two original canopied entrances by Guimard.

Organization

editThe first international exposition was held in London in 1851. The French Emperor Napoleon III attended and was deeply impressed. He commissioned the first Paris Universal Exposition of 1855. Its purpose was to promote French commerce, technology and culture. It was followed by another in 1867, and, after the Emperor's downfall in 1870, another in 1878, celebrating national unity after the defeat of the Paris Commune, and then in 1889, celebrating the centennial of the French Revolution.[1][2]

Planning for the 1900 Exposition began in 1892, under President Carnot, with Alfred Picard as Commissioner-General. Three French Presidents and ten Ministers of Commerce held office before it was completed. President Carnot died shortly before it was completed. Though many of the buildings were not finished, the exposition was opened on 14 April 1900 by President Émile Loubet.[3][2]

-

Opening ceremony on 14 April 1900

Participating nations

editCountries from around the world were invited by France to showcase their achievements and cultures. Of the fifty-six countries invited to participate with official representation, forty accepted, plus an additional number of colonies and protectorates of France, the Netherlands, Great Britain, and Portugal.[4]

| Participating nations[5] |

|---|

Austria, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Hungary participated as independent nations, although belonging to Austria-Hungary at that time. Finland, although having a national pavilion located at the Rue des Nations, officially participated as part of Russia. Egypt, also with an own pavilion, participated as part of Turkey. The few exhibitors from countries without an official presence at the Fair participated under a joint "International Section".[5]

Among the colonies and protectorates present in the Fair were French Algeria, Cambodia, Congo, Dahomey, Guadeloupe, Guiana, Guinea, India, Indochina, Ivory Coast, Laos, Madagascar, Martinique, Mayotte, New Caledonia, Oceania, Réunion, Senegal, Somaliland, Sudan, Tonkin, Tunisia, West Africa, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, the Dutch East Indies, British Canada, Ceylon, India and Western Australia and the Portuguese colonies.[5]

Exposition site

editThe site of the exposition covered 112 hectares (280 acres) along the left and right banks of the Seine from the esplanade of Les Invalides to the Eiffel Tower (built for the 1889 Exposition) at the Champ de Mars. It also included the Grand Palais and Petit Palais on the right bank. An additional section of 104 hectares (260 acres) for agricultural exhibits and other structures was built in the Bois de Vincennes. The total area of the exposition, 216 hectares (530 acres), was ten times larger than the 1855 Exposition.[4]

The exposition buildings were meant to be temporary; they were built on iron frames covered with plaster and staff, a kind of inexpensive artificial stone. Many of the buildings were unfinished when the exposition opened, and most were demolished immediately after it closed.

-

Aerial view of the Exposition Universelle

-

Map of the exposition

-

Poster with the world leaders[b]

The Porte Monumentale

editThe Porte Monumentale de Paris, located on the Place de la Concorde, was the main entrance of the exposition. The architect of the monument overall was René Binet, although many others contributed to the constituent parts. His overall design was inspired by the biological studies of Ernst Haeckel. It was composed of towering polychrome ceramic decoration in Byzantine motifs, crowned by a statue 6.5 metres (21 ft) high called La Parisienne.[6] Unlike classical statues, she was dressed in modern Paris fashion. La Parisienne was executed by sculptor Paul Moreau-Vauthier who collaborated with Paris' pre-eminiment haute couturier of the day, Jeanne Paquin, who designed the figure's fashionable attire.[7] Below the statue was a sculptural prow of a boat, the symbol of Paris, and friezes depicting the workers who built the exposition. The central arch was flanked by two slender, candle-like towers, resembling minarets. The gateway was brightly illuminated at night by 3,200 light bulbs and an additional forty arc lamps. Forty thousand visitors an hour could pass beneath the arch to approach the twenty-six ticket booths.[8][9] Above the ticket booth windows, the names of provincial cities were inscribed, symbolically enacting a hierarchical relation between Paris and the provinces.[10]

The structure of the entrance tower as a whole was adorned with Byzantine motifs and Persian ceramic ornamentation, but the true inspiration behind the piece was not of cultural background.[9] Binet sought inspiration from science, tucking the vertebrae of a dinosaur, the cells of a beehive, rams, peacocks, and poppies into the design alongside other animalistic stimuli.[9]

The Gateway, like the exposition buildings, was intended to be temporary, and was demolished as soon as the exposition was finished. The ceramic frieze depicting the workers of the exposition was designed by Anatole Guillot, an academic sculptor. The workers frieze was preserved by the head of the ceramics firm that made it, Émile Müller, and moved to what is now Parc Müller in the town of Breuillet, Essonne. The workers were situated above a frieze of animals designed by sculptor Paul Jouve and executed by ceramicist Alexandre Bigot.

-

Porte Monumentale on the Place de la Concorde

-

Detail of the Porte Monumentale entrance

The Pont Alexandre III

editThe Pont Alexandre III was an essential link of the exposition, connecting the pavilions and palaces on the left and right banks of the Seine. It was named after Czar Alexander III of Russia, who had died in 1894, and celebrated the recent alliance between France and Russia. The foundation stone was laid by his son, Czar Nicholas II in 1896, and the bridge was finished in 1900. It was the work of engineers Jean Resal and Amédée D'Alby and architect Gaston Cousin. The widest and longest of the Paris bridges at the time, it was constructed on a single arch of steel 108 metres (354 ft) long. Though it was named after the Russian Czar, the themes of the decoration were almost entirely French. At the ends, the bridge was supported by four massive stone pylons 13 metres (43 ft) high, decorated with statues of the Renomées (The Renowned), female figures with trumpets, and gilded statues of the horse Pegasus. At the base of the pedestals are allegorical statues representing the France of Charlemagne, the France of the Renaissance, the France of Louis XIV and France in 1900.[11] The Russian element was in the center, with statuary of the Nymphs of the Neva River holding a gilded seal of the Russian Empire. At the same time that the Pont Alexander III was built, a similar bridge, the Trinity Bridge was built in Saint-Petersburg, and was dedicated to French-Russian friendship by French President Félix Faure.

-

View of the Pont Alexandre III toward Les Invalides

-

The Pont Alexandre III with the Grand Palais (left) and the Petit Palais (right) in the background

-

View of the Seine from the Pont Alexandre III

Thematic pavilions

editTo house the industrial, commercial, scientific, technological and cultural exhibitions, the French organization built huge thematic pavilions on the esplanade of Les Invalides and the Champ de Mars and reused the Galerie des machines from the 1889 Exposition. On the other bank of the Seine, they built the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais for the fine arts exhibitions.[12]

The 83,047 French and foreign exhibitors at the Fair were divided into eighteen groups based on their subject matter, which in turn were divided into 121 classes, and based on the class to which they belonged, they were allocated in the corresponding official thematic pavilion. Each thematic pavilion was divided into national sections, which were the responsibility of the corresponding country and where its exhibitors were located. Some country with a strong presence in a specific sector, at its own request, was even granted a plot adjoining to the main building to build a small pavilion to house its exhibitors.[12]

The Palaces of Optics, Illusions and Aquarium

editTwenty-one of the thirty-three official pavilions were devoted to technology and the sciences. Among the most popular was the Palace of Optics, whose main attractions included the Great Paris Exposition Telescope, which enlarged the image of the moon ten thousand times. The image was projected on a screen 144 square metres (1,550 sq ft) in size, in a hall which seated two thousand visitors. This telescope was the largest refracting telescope at that time. The optical tube assembly was 60 metres (200 ft) long and 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) in diameter, and was fixed in place due to its mass. Light from the sky was sent into the tube by a movable 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) mirror.

Another very popular feature of the Palace of Optics was the giant kaleidoscope, which attracted three million visitors. Other features of the optics pavilion included demonstrations of X-rays and dancers performing in phosphorescent costumes.

The Palais des Illusions (Palace of Illusions), adjoining the Palace of Optics, was an extremely popular exhibition. It was a large hall which used mirrors and electric lighting to create a show of colorful and bizarre optical illusions. It was preserved after the exposition in the Musée Grévin.[13]

Another scientific attraction was the aquarium, the largest in the world at the time, viewed from an underground gallery 722 metres (2,369 ft) long. The water tanks were each 38 metres (125 ft) long, 18 metres (59 ft) wide and 6.5 metres (21 ft) deep, and contained a wide selection of exotic marine life.

-

Entrance of the Palace of Optics

-

Diagram of the Great Paris Exhibition Telescope of 1900

-

The Palais des Illusions created a show of optical illusions with mirrors and lighting effects.

The Palace of Electricity and the Water Castle

editThe Palace of Electricity and the adjoining Water Castle (Chateau d'Eau), designed by architects Eugène Hénard and Edmond Paulin,[9] were among the most popular sights. The Palace of Electricity was built partly incorporating architectural elements of the old Palace of the Champ de Mars from the 1889 Exposition. The Palace was enormous, 420 metres (1,380 ft) long and 60 metres (200 ft) wide, and its form suggested a giant peacock spreading its tail. The central tower was crowned by an enormous illuminated star and a chariot carrying a statue of the Spirit of Electricity 6.5 metres (21 ft) high, holding aloft a torch powered by 50,000 volts of electricity, provided by the steam engines and generators inside the Palace. Electrical lighting was used extensively to keep the Fair open well into the night. Producing the light for the exposition consumed 200,000 kilograms (440,000 lb) of oil an hour.[14] The facade of the Palace and the Water Castle, across from it, were lit by an additional 7,200 incandescent lamps and seventeen arc lamps.[15][9] Visitors could go inside to see the steam-powered generators which provided electricity for the buildings of the exposition.[9][2]

The Water castle, facing the Palace of Electricity, had an equally imposing appearance. It had two large domes, between which was a gigantic fountain, circulating 100,000 litres (22,000 imp gal; 26,000 US gal) of water a minute. Thanks to the power from Palace of Electricity, the fountain was illuminated at night by continually changing colored lights.[14]

-

The Palace of Electricity (behind) and the Water Castle (in front)

The Grand Palais and Petit Palais

editThe Grand Palais, officially the Grand Palais des beaux-arts et des arts decoratifs, was built on the right bank upon the site of the Palace of Industry of the 1855 Exposition. It was the work of two architects, Henri Deglane for the main body of the building, and Albert Thomas for the west wing, or Palais d'Antin. The iron frame of the Grand Palais was quite modern for its time; it appeared light, but in fact, it used 9,000 tonnes (8,900 long tons; 9,900 short tons) of metal, compared with seven thousand for the construction of the Eiffel Tower.[16] The facade was in the ornate Beaux-Arts style or Neo-Baroque style. The more modern interior iron framework, huge skylights and stairways offered decorative elements in the new Art Nouveau style,[9] particularly in the railings of the staircase, which were intricately woven in fluid, organic forms.[2] During the Fair, the interior served as the setting for the exhibitions of paintings and sculptures.[9] The main body of the Grand Palais housed the Exposition décennale des beaux-arts de 1889 à 1900 with the paintings of French artists in the north wing, the paintings of artists from other countries in the south wing and the sculptures in the central hall, with some outdoor sculptures nearby.[17] The Palais d'Antin, or west wing, housed the Exposition centennale de l'art français de 1800 à 1889.[18]

The Petit Palais, that is facing the Grand Palais, was designed by Charles Girault.[9] Much like the Grand Palais, the facade is Beaux-Arts and Neo-Baroque, reminiscent of the Grand Trianon and the stable at Chantilly.[9] The interior offers examples of Art Nouveau, particularly in the railings of the curving stairways, the tiles of the floors, the stained glass, and the murals on the ceiling of the arcade around the garden.[9] The entrance murals were painted by Paul-Albert Besnard and Paul Albert Laurens.[9] During the Fair, the Petit Palais housed the Exposition rétrospective de l'art français des origines à 1800.[19]

-

Grand Palais central hall with the exhibition of sculptures

-

Courtyard of the Petit Palais

The Palaces of Industry, Decoration and Agriculture

editThe industrial and commercial exhibits were located inside several large palaces on the esplanade between les Invalides and the Alexander III Bridge. One of the largest and most ornate was the Palais des Manufactures Nationale, whose facade included a colorful ceramic gateway, designed by sculptor Jules Coutan and architect Charles Risler and made by the Sèvres Porcelain manufactory. After the exposition it was moved to the wall of Square Felix-Déésroulles, next to the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, where it can be seen today.[20]

The Palace of Furniture and Decoration was particularly lavish and presented many displays of the new Art Nouveau style.

The Palace of Agriculture and Food was inside the former Galerie des machines, an enormous iron-framed building from the 1889 Exposition. Its most popular feature was the Champagne Palace, offering displays and samples of French Champagne.

-

The Palace of National Manufacturers (left), with the Italian pavilion in distance

-

United States section at the Palace of Furniture and Decoration

-

Austrian section at the Palace of Furniture and Decoration

-

Pavilion of Agriculture and Food, inside the former Palace of Machines of the 1889 Exposition.

-

The Champagne Palace at the Palace of Agriculture and Food

National pavilions

editFifty-six countries were invited to the exposition, and forty accepted. The Rue des Nations was created along the banks of the Seine between the esplanade of Les Invalides and the Champ de Mars for the national pavilions of the larger countries. Each country paid for its own pavilion. The pavilions were all temporary, made of plaster and staff on a metal frame and were designed in an architectural style that represented a period in the country's history, often imitating famous national monuments.[2]

At the Rue des Nations, on the left bank of the Seine, on the Quai d'Orsay, overlooking the river, from the Pont des Invalides towards the Pont de l'Alma, were located the national pavilions of Italy, Turkey, the United States, Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hungary, Great Britain, Belgium, Norway, Germany, Spain, Monaco, Sweden, Greece, Serbia and Mexico. Behind them, in second line, were located the pavilions of Denmark, Portugal, Peru, Persia, Finland, Luxembourg, Bulgaria and Romania. The other nations were located elsewhere in the exposition site.[2]

In addition to their own national pavilion, the countries managed other spaces at the Fair. The industrial, commercial, scientific and cultural exhibitors of each country were distributed among the national sections of the different official thematic pavilions.[2]

The Rue des Nations

editThe pavilion of Turkey was designed by a French architect, Adrien-René Dubuisson, and was a mixture of copies of Islamic architecture from mosques in Istanbul and elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire. Turkey managed 4,000 square metres (43,000 sq ft) of exhibition space at the Fair.[21]

The United States pavilion was modest, a variation on the United States Capitol Building designed by Charles Allerton Coolidge and Georges Morin-Goustiaux. The main U.S. presence was in the commercial and industrial palaces. One unusual aspect of the U.S. presence was The Exhibit of American Negroes at the Palace of Social Economy, a joint project of Daniel Murray, the Assistant Librarian of Congress, Thomas J. Calloway, a lawyer and the primary organizer of the exhibit, and W. E. B. Du Bois. The goal of the exhibition was to demonstrate progress and commemorate the lives of African Americans at the turn of the century.[22] The exhibit included a statuette of Frederick Douglass, four bound volumes of nearly 400 official patents by African Americans, photographs from several educational institutions (Fisk University, Howard University, Roger Williams University, Tuskegee Institute, Claflin University, Berea College, North Carolina A&T), and, most memorably, some five hundred photographs of African-American men and women, homes, churches, businesses and landscapes including photographs from Thomas E. Askew.[23]

The pavilions of the Austro-Hungarian domains in the Balkans, Bosnia and Herzegovina, offered displays on their lifestyles, consisting of folklore traditions, highlighting peasanthood and the embroidery goods produced in the country.[9] Designed by Karl Panek, it featured murals on the history of Slavic peoples by Alphonse Mucha.

The pavilion of Hungary was designed by Zoltán Bálint and Lajos Jámbor. Its cupola displayed agricultural produce and hunting equipment.[9]

The British Royal pavilion consisted of a mock-Jacobean mansion designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens that was decorated with pictures and furniture. The furnishings designed by Nellie Whichelo included hangings that were more than 12 by 13 feet (3.7 by 4.0 m), which had taken 56 ladies six weeks to embroider.[24] The pavilion was largely used for receptions for important visitors to the exposition.[2]

The German pavilion was the tallest, at 76 metres (249 ft), designed by Johannes Radke and built of wood and stained glass. However, most of the German presence at the exposition was in the commercial pavilions, where they had important displays of German technology and machinery, as well as models of German steamships and a full-scale model of a German lighthouse.[2]

The Royal Pavilion of Spain was designed in Neo-Plateresque style by José Urioste Velada. It housed the Retrospective Exhibition of Spanish Art formed by the collection of tapestries, in which thirty-seven pieces made between the 15th and 18th centuries from the Royal Collections were exhibited. The pavilion basement housed a Spanish-themed café-restaurant, named La Feria, that was the first restaurant in History with a completely electric kitchen.[25]

Sweden's yellow and red structure covered in pine shingles drew attention with its bright colours. It was designed by Ferdinand Boberg.[2]

Serbia presented itself with a 550 square metres (5,900 sq ft) pavilion resembling a church, in the Serbo-Byzantine style whose main architect was Milan Kapetanović from Belgrade, in cooperation with architect Milorad Ruvidić. Serbia presented numerous products at the exposition, such as wine, food, fabrics, minerals and won a total of 19 gold, 69 silver and 98 bronze medals. Some of the Serbian fine art on display were the painting The Proclamation of Dušan's Law Codex by Paja Jovanović and Monument to heroes of Kosovo by Đorđe Jovanović, which stands today in Kruševac.[26][27]

The pavilion of Finland, designed by Gesellius, Lindgren, Saarinen, had clean-cut, modern architecture.[2]

-

Rue des Nations. From left to right: Pavilions of Belgium, Norway, Germany, Spain, Monaco, Sweden, Greece and Serbia.

-

Pavilion of Italy by Carlo Ceppi, Costantino Gilodi and Giacomo Salvadori

-

Pavilion of Turkey by Adrien-René Dubuisson

-

Pavilion of the United States by Coolidge and Morin-Goustiaux

-

Pavilions of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Karl Panek (left) and Hungary by Zoltán Bálint and Lajos Jámbor (right)

-

Pavilion of Belgium by Ernest Acker and Gustave Maukels

-

Pavilion of Germany by Johannes Radke

-

Royal Pavilion of Spain by José Urioste Velada

-

Pavilion of Monaco by Jean Marquet and François Medecin

-

Pavilion of Sweden by Ferdinand Boberg

-

Pavilion of Greece by Lucien Magne

-

Pavilion of Serbia by Milan Kapetanović and Milorad Ruvidić

-

Pavilion of Finland by Gesellius, Lindgren, Saarinen

Nations located elsewhere

editRussia had an imposing presence on the Trocadéro hill. The Russian pavilion, designed by Robert Meltzer, was inspired by the towers of the Kremlin and had exhibits and architecture presenting artistic treasures from Samarkand, Bukhara and other Russian dependencies in Central Asia.[28]

The Chinese pavilion, designed by Louis Masson-Détourbet, was in the form of a Buddhist temple with staff in Chinese traditional dress. This pavilion suffered some disruption in August 1900, when anti-Western rebels seized the International delegations in Beijing in the Boxer Rebellion and held them for several weeks until an expeditionary force from the Eight-Nation Alliance arrived and recaptured the city. During the disruption at the Fair, a Chinese procession was attacked by angered Parisians.[29]

The Korean pavilion, designed by Eugène Ferret, was mostly stocked by French Oriental collectors, including Victor Collin de Plancy, with a supplement of Korean goods from Korea.[30] One object of note on display was the Jikji, the oldest extant book printed with movable metal type.[31]

Morocco had its pavilion near the Eiffel Tower and was designed by Henri-Jules Saladin.[28]

-

Pavilion of Russia by Robert Meltzer

-

Pavilion of China by Louis Masson-Détourbet

-

Pavilion of Morocco by Henri-Jules Saladin

Colonial pavilions

editAn area of several dozen hectares on the hill of the Trocadéro Palace was set aside for the pavilions of the colonies and protectorates of France, the Netherlands, Great Britain, and Portugal.

The largest space was for the French colonies in Africa, the Caribbean, the Pacific and Southeast Asia. These pavilions featured traditional architecture of the countries and displays of local products mixed with modern electric lighting, motion pictures, dioramas, and guides, soldiers, and musicians in local costumes. The French Caribbean islands promoted their rum and other products, while the French colony of New Caledonia highlighted its exotic varieties of wood and its rich mineral deposits.[28]

The North African French colonies were especially present; The Tunisian pavilion was a miniature recreation of the Sidi Mahrez Mosque of Tunis. Algeria, Sudan, Dahomey, Guinea and the other French African colonies presented pavilions based on their traditional religious architecture and marketplaces, with guides in costume.[28]

The French colonies of Indochina, Tonkin and Cambodia also had an impressive presence, with recreations of pagodas and palaces, musicians and dancers, and a recreation of a riverside village from Laos.[28]

The Netherlands displayed the exotic culture of its crown colony, the Dutch East Indies. The pavilion displayed a faithful reconstruction of 8th-century Sari temple and also Indonesian vernacular architecture of Rumah Gadang from Minangkabau, West Sumatra.

-

Pavilion of French Algeria by Albert Ballu

-

Pavilion of French Tunisia by Henri-Jules Saladin

-

Pavilion of Cambodia - Buddhist Temple

Attractions

editBesides its official scientific, industrial and artistic palaces, the exposition offered an extraordinary variety of attractions, amusements and diversions.

Eiffel Tower

editThe Eiffel Tower, that was built as the main entrance of the 1889 Exposition, was the main and central attraction of the 1900 Exposition. For this exposition, it was repainted in shaded tones from yellow-orange at the base to light yellow at the top, and was fitted with 7,000 electric lamps. At the same time, the lifts in the east and west legs were replaced by lifts running as far as the second level and the lift in the north pillar was removed and replaced by a staircase to the first level. The layout of both first and second levels was modified, with the space available for visitors on the second level.[32]

-

Aerial view of the exposition including the Eiffel Tower

-

View of the Champ de Mars under the Eiffel Tower

The Grande Roue de Paris

editThe Grande Roue de Paris was a very popular attraction. It was a gigantic ferris wheel 110 metres (360 ft) high, which took its name from a similar wheel created by George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It could carry 1,600 passengers in its forty cars in a single voyage. The cost of a ride was one franc for a second class car, and two francs for a more spacious first-class car. Despite the high price, passengers often had to wait an hour for a place.[33]

-

The Grande Roue at the Paris Exposition could carry 1600 passengers at once

The moving sidewalk, electric train and electrobus

editThe Rue de l'Avenir (transl. Street of the future) moving sidewalk was a very popular and useful attraction, given the large size of the exposition. It ran along the edge of the exposition, from the esplanade of Les Invalides to the Champ de Mars, passing through nine stations along the way, where passengers could board. The fare was an average of fifty centimes. The sidewalk was accessed from a platform 7 metres (23 ft) above the ground level. The passengers stepped from the platform onto the moving sidewalk traveling at 4.2 kilometres per hour (2.6 mph), then onto a more rapid sidewalk moving at 8.5 kilometres per hour (5.3 mph). The sidewalks had posts with handles which passengers could hold onto, or they could walk. It was designed by architect Joseph Lyman Silsbee and engineer Max E. Schmidt.[34]

A Decauville electric train followed the same route, running at an average speed of 17 kilometres per hour (11 mph) in the opposite direction of the moving sidewalk. The rail track was sometimes at 7 metres (23 ft) high like the movable sidewalks, sometimes at ground level and sometimes underground.[35]

An experimental passenger electrobus line, designed by Louis Lombard-Gérin, ran in the Bois de Vincennes from 2 August to 12 November 1900. It was a 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) long circular route connecting the recently opened Porte de Vincennes metro station with Lac Daumesnil. It was the first trolleybus in regular passenger service in History.[36]

-

Quai d'Orsay-Pont des Invalides station of the moving sidewalk near the Pavilion of Italy

-

Viaducts of the electric train (left) and the moving sidewalk (right)

-

The first ever trolleybuses in regular passenger service (Bois de Vincennes)

The Globe Céleste

editThe Globe Céleste was an immense globe-shaped planetarium which offered a presentation on the night sky. The globe, designed by Napoléon de Tédesco, was 45 metres (148 ft) in diameter, and the blue and gold exterior was painted with the constellations and the signs of the zodiac. It was placed atop a masonry support 18 metres (59 ft) high, supported by four columns. A flower garden on the support surrounded the globe. Spectators seated in armchairs inside watched a presentation on the stars and planets projected overhead.

The sphere was the scene of a fatal accident on 29 April 1900 when one of access ramps, hastily made of a newly introduced material, reinforced concrete, collapsed onto the street below, killing nine people. Following the accident the French government established the first regulations for the use of reinforced concrete.

-

The Globe Céleste and the Eiffel Tower

-

The Globe Céleste was featured in an advertisement for Suchard Chocolate

Motion pictures

editThe Lumière brothers, who had made the first public projections of a motion picture in 1895, presented their films on a colossal screen, 21 metres (69 ft) by 16 metres (52 ft), in the Gallery of Machines. Another innovation in motion pictures was presented at the exposition at the Phono-Cinema Theater; a primitive talking motion picture, where the image on the screen was synchronized to the sound from phonographs.[37]

An even more ambitious experiment in motion pictures was the Cinéorama of Raoul Grimoin Sanson, which simulated a voyage in a balloon. The film, projected on a circular screen 93 metres (305 ft) in circumference by ten synchronized projectors, depicted a landscape passing below. The spectators sat in the center above the projectors, in what resembled the basket suspended beneath a large balloon.[37]

Another popular attraction was the Mareorama, which simulated a voyage by ship from Villefranche to Constantinople. The viewers stood on the railing of a ship simulator, watching painted images pass by of the cities and seascapes en route. The illusion was aided by machinery that rocked the ship, and fans which blew gusts of wind.[38]

-

Poster for the Phono-Cinema Theater

-

The Cinéorama, a simulated voyage in a balloon with motion pictures projected on a circular screen.

-

The Mareorama simulated a sea voyage, complete with rocking ship and unrolling painted scenery.

World live recreations

editL'Andalousie au temps des Maures (transl. Andalusia In The Time Of The Moors) was a 5,000 m2 (54,000 sq ft) Spanish-themed open air attraction with folkloric live performances at Quai Debilly, at the western end of Trocadéro, on the right bank of the Seine, featuring full-scale moorish architecture reproductions from the Alhambra, Córdoba, Toledo, the Alcázar of Seville and a 80 m (260 ft) tall reproduction of the Giralda. It was a French-produced attraction that had no relation with the official representation of Spain at the Fair.[39]

-

Poster from a painting by Ulpiano Checa

-

Bullring and Giralda

-

Recreation of the Alhambra

Le Vieux Paris (transl. Old Paris) was a recreation of the streets of old Paris, from the Middle Ages to the 18th century, with recreations of historic buildings and streets filled with performers and musicians in costumes. It was built following an idea by Albert Robida.[40] There were also several recreations depicting picturesque or touristic regions of France, including exhibitions from Provence, Bretagne, Poitou, Berry and Auvergne, using their pre-revolutionary provincial names rather than their departments. Provence was represented by two reconstructions, a Provençal farmhouse or mas and a reconstruction called Vieil Arles which reconstructed certain Roman ruins and part of the town's cathedral.[41]

The Swiss Village, at the edge of the exposition near Avenue de Sufren and Motte-Piquet, was a recreation of a Swiss mountainside village, complete with a 35 metres (115 ft) cascade, a lake and collection of thirty-five chalets.[40]

The Panorama du Tour du Monde was an animated panorama journey from Europe to Japan in a building by Alexandre Marcel in the architectural styles of India, China, Cambodia, Japan and Renaissance Europe. It consisted in panoramic paintings by Louis Dumoulin in front of which groups of native people, dressed accordingly, move, play, dance, stroll or work. The visitor traveled through representations of Fuenterrabía (Spain), the Pnyx hill in Athens (Greece), the cemetery of Stamboul and the Golden Horn of Constantinople (Turkey), Syria, the Suez Canal (Egypt), Ceylon, the Angkor Wat temple (Cambodia), Shanghai (China) and Nikkō (Japan). The visit continued by showing dioramas of Rome, Moscow, New York and Amsterdam and ended with a mobile panorama of a boat trip along the coast of Provence, from Marseille to La Ciotat. It was funded and sponsored by the Compagnie des messageries maritimes.[42]

Other recreations with costumed vendors and musicians elsewhere the exposition included recreations of the bazaars, souks and street markets of Algiers, Tunis and Laos, a Venetian canal with gondolas, a Russian village and a Japanese tea house.[40]

-

Le Vieux Paris exterior

-

Le Vieux Paris

-

The Swiss Village

-

Panorama du Tour du Monde

Theatres and music halls

editThe exposition had several large theatres and music halls, the largest of which was the Palais des Fêtes, which had fifteen thousand seats, and offered programs of music, ballet, historical recreations and diverse spectacles. A separate thoroughfare of the exposition, the Rue de Paris, was lined with amusements, including music venues, a comedy theater, marionettes, American jazz, a Grand Guignol theater, and the celebrated "Backwards House", which had its furniture on the ceiling, its chandeliers on the floor, and windows which gave reverse images. Other diversions elsewhere in and around the exposition included an orchestra from Madagascar, a Comedy Theater, and the Columbia Theater at Port Maillot, with acts ranging from panoramas of life in the Orient to a water ballet. These diversions were popular but expensive; entry to the Comedy Theater cost up to five francs.[43]

The most celebrated actress during the exposition was Sarah Bernhardt, who had her own theater, The Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt (now the Théâtre de la Ville), and premiered one of her most famous roles during the exposition. This was L'Aiglon, a new play by Edmond Rostand in which she played the Duc de Reichstadt, the son of Napoleon Bonaparte, imprisoned by his unloving mother and family until his melancholy death in the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna. The play ended with a memorable death scene; according to one critic, she died "as dying angels would die if they were allowed to."[44] The play ran for nearly a year, with standing-room places selling for as much as 600 gold francs.[45]

Another popular diversion during the exposition was the theater of the American dancer, Loie Fuller, who performed a famous Serpentine dance in which she waved large silk scarves which seemed to envelop her into a cloud. Her performance was widely reproduced in photographs, paintings and drawings by Art Nouveau artists and sculptors, and were captured in very early motion pictures.[2] She was filmed on ten 70mm projectors that created a 330-degree picture, patented by Cinéorama.[2]

-

The dancer Loie Fuller had her own theater in Paris during the 1900 Exposition

-

Sarah Bernhardt as L'Aiglon, the son of Napoleon Bonaparte, played to full houses in her theater during the exposition.

Events

editMany international congresses and other events were held in Paris in 1900 within the framework of the exposition. A large area within the Bois de Vincennes was set aside for sporting events, which included, among others, many of the events of the 1900 Summer Olympics. A chess tournament was also held.

1900 Summer Olympics Games

editThe 1900 Summer Olympics were the second modern Olympics games held, and the first ones held outside Greece. Between 14 May and 28 October 1900, an enormous number of sporting activities were held along the exposition. The sporting events rarely used the term of "Olympic". Indeed, the term "Olympic Games" was replaced by "Concours internationaux d'exercices physiques et de sport" (transl. "International physical exercises and sports competition") in the official report of the exposition. The press reported competitions variously as "International Championships", "International Games", "Paris Championships", "World Championships" and "Grand Prix of the Paris Exposition". The International Olympic Committee (IOC) had no real control over the organization, no official interpretation has ever been made and various sources list differing events, further adding to the confusion that was Paris 1900.[46]

According to the IOC, 997 competitors took part in nineteen different sports, including women competing for the first time.[47] A number of events were held for the first and only time in Olympic history, including automobile and motorcycle racing, ballooning, cricket, croquet, a 200 metres (660 ft) swimming obstacle race and underwater swimming.[48] France provided 72 percent of all athletes (720 of the 997) and won the most gold, silver and bronze medal placings. The United States athletes won the second largest number, with just 75 of the 997 athletes.[49] The pigeon race was won by a bird that flew from Paris to its home in Lyon in four and a half hours. The free balloon competition race was won by a balloon which travelled 1,925 kilometres (1,196 mi) from Paris to Russia in 35 hours and 45 minutes.[50]

-

Gymnasts at opening ceremony (Bois de Vincennes)

-

Hélène Pévost, French women's tennis champion at the 1900 Paris Olympics, the first games in which women competed

-

A combined Swedish-Danish team defeated France in the Olympic Tug-of-War competition

-

Beginning of the balloon event at the 1900 Summer Olympics (Bois de Vincennes)

Banquet des maires

editAnother special event at the exposition was a gigantic banquet hosted by the French President, Émile Loubet, for 20,777 mayors of France, Algeria and towns in French colonies, hosted on 22 September 1900 in the Tuileries Gardens, inside two enormous tents.[50] The dinner was prepared in eleven kitchens and served to 606 tables, with the orders and needs of each table supervised by telephone and vehicle.[2]

Medals and awards ceremony

editThe organizers of the exposition were not miserly in recognizing the 83,047 exhibitors of products, about half of whom came from France, and 7,161 from the United States. The awards ceremony was held on 18 August 1900, and was attended by 11,500 persons. 3,156 grand prizes were handed out, 8,889 gold medals, 13,300 silver medals, 12,108 bronze medals, and 8,422 honorable mentions. Many of the participants, such as Campbell's Soup or Michigan Stove Company, added the Paris award to the advertisements and labels of their products.[51]

Admission charges and cost

editThe cost of an admission ticket was one franc. At the time, the average hourly wage for Paris workers was between forty and fifty centimes. In addition, most popular attractions charged an admission fee, usually between fifty centimes and a franc. The average cost of a simple meal at the exposition was 2.50 francs, the half-day wages of a worker.[52] The amount budgeted for the Paris Exposition was one hundred million francs; twenty million from the French State, twenty million from the City of Paris, and the remaining sixty million expected to come from admissions, and backed by French banks and financial institutions.[53]

The official final cost was 119 million francs, while the total amount actually collected from admission fees was 126 million francs. However, there were unplanned expenses of twenty-two million francs for the French State, and six million francs for the City of Paris, bringing the total cost to 147 million francs, or a deficit of twenty-one million francs.[53] The deficit was to a degree offset by the long-term additions to the city infrastructure; new buildings and bridges, including the Grand and Petit Palais, the Pont Alexander III and the Passerelle Debilly; and additions to the transport system; The Paris Métro Line 1, the funicular railway on Montmartre, and two new train stations, the Gare d'Orsay and the Gare des Invalides, and the new facade and enlargement and redecoration of the Gare de Lyon and other stations.

The exposition was so expensive to organize and run that the cost per visitor ended up being about six hundred francs more than the price of admission. The exhibition lost a grand total of 82,000 francs after six months in operation. Many Parisians had invested money in bonds sold to raise money for the event and therefore lost their investment. With a much larger than expected turnout the exhibit sites had gone up in value. Continuing to pay rent for the sites became increasingly hard for concessionaires as they were receiving fewer customers than anticipated. The concessionaires then went on strike, which ultimately resulted in the closure of a large part of the exposition. To resolve the matter, the concessionaires were given a fractional refund of the rent they had paid.[2]

Art Nouveau at the exposition

editThe Art Nouveau ("New Art") style began to appear in Belgium and France in the 1880s and became fashionable in Europe and the United States during the 1890s.[54] It was highly decorative and took its inspiration from the natural world, particularly from the curving lines of plants and flowers and other vegetal forms. The architecture of the exposition was largely of the Belle Epoque style and Beaux-Arts style, or of eclectic national styles. Art Nouveau decoration appeared in the interiors and decoration of many of the buildings, notably the interior ironwork and decoration of the Monumental gateway of the exposition, the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais, and in the portal of the Palace of National Industries.

The Art Nouveau style was very popular in the pavilions of decorative arts. The jewelry firm of Fouquet and the glass and crystal manufactory of Lalique all presented collections of Art Nouveau objects.[55] The Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory created a series of monumental swan vases for the exposition, as well as the monumental entrance to the Palace of National Manufacturers.[55]

Many exposition posters also made use of the Art Nouveau style. The work of the most famous Art Nouveau poster artist, Alfons Mucha, had many forms at the exposition. He designed the posters for the official Austrian participation in the exposition, painting murals depicting scenes from the history of Bosnia as well as the menu for the restaurant at the Bosnian pavilion, and designed the menu for the official opening banquet. He produced displays for the jeweler Georges Fouquet and the perfume maker Houbigant, with statuettes and panels of women depicting the scents of rose, orange blossom, violet and buttercup. His more serious art works, including his drawings for Le Pater, were shown in the Austrian pavilion and in the Austrian section of the Grand Palais. Some of his murals can be seen now in the Petit Palais.[56]

The most famous appearance was in the entrances of the stations of the Paris Métro designed by Hector Guimard. It also appeared in the interior decoration of many popular restaurants, notably the Pavillon Bleu at the exposition, Maxim's, and the Le Train Bleu restaurant of the Gare de Lyon,[57] and in the portal of the Palace of National Manufacturers made by the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory.[54]

The exposition was a showcase not only of French Art Nouveau, but also the variations that had appeared in other parts of Europe, including the furniture of the Belgian architect and designer Victor Horta, designs of the German Jugendstil by Bruno Möhring, and of the Vienna Secession of Otto Wagner. Their display at the exposition brought the new style international attention.[57]

-

Art Nouveau swan vase by the Sèvres Manufactory made for the exposition

-

Nymph lamp by Egide Rombaux & François Hoosemans made for the exposition

-

Menu by Alfons Mucha for the restaurant of the Bosnia and Herzegovina pavilion

-

Bosnia and Herzegovina pavilion murals by Alfons Mucha (1900), now in Petit Palais

-

The Bigot pavilion, showcasing the work of Art Nouveau ceramics manufacturer Alexandre Bigot

-

The 1900 interior of the Train Bleu at the Gare de Lyon

-

1893 facade of Maxim's restaurant

Legacy

editMost of the palaces and buildings constructed for the Exposition Universelle were demolished after the conclusion of the exposition and all items and materials that could be salvaged were sold or recycled. They were built largely of wood and covered with staff, which was formed into columns, statuary, walls, stairs. A few of the major structures built for the exposition were preserved, including the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais, and the two major bridges, the Pont Alexandre III and the Passerelle Debilly, though the latter was later dismantled and moved a few dozen meters from its original placement.[58]

The Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris (CMP) installed a total of 141 of the Art Nouveau metro station entrances designed by Hector Guimard –with and without canopy– between 1900 and 1913. In 1978, the 86 entrances that still existed were protected as historical monuments and have been preserved to this day, including two original canopied ones: at Porte Dauphine, on its original site and with the wall panels, and at Abbesses (moved from Hôtel de Ville in 1974). A third canopied entrance at Châtelet is a 2000 recreation. None of the three pavilion-type entrances designed by Guimard have survived.[59]

The monumental portal of the Palace of National Manufacturers, made by the Sèvres Manufactory, was preserved and moved to Square Felix-Desruelles, next to the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

A 2.87 metres (9 ft 5 in) copy of the Statue of Liberty by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi exhibited at the Fair, was placed in the Luxembourg Gardens in 1905 at the request of his widow.

After visiting the Panorama du Tour du Monde, King Leopold II of Belgium commissioned the architect of the building, Alexandre Marcel, to build a Japanese tower and a Chinese pavilion in the Royal Domain of Laeken, Brussels, Belgium. Marcel rebuilt there the Japanese red pagoda of the Panorama du Tour du Monde (now known as the Japanese Tower) and moved there the original entry pavilion to the tower from Paris. He also built the Chinese Pavilion whose wooden panelling was sculpted in Shanghai. Both structures are now part of the Museums of the Far East.[60]

One of the most curious vestiges is La Ruche, at 2 Passage de Dantzig (15th arrondissement). This is a three-story building constructed entirely out of bits and pieces of exposition buildings, purchased at auctions by sculptor Alfred Boucher. The iron roof, made by Gustave Eiffel, originally covered the kiosk of the Wines of Médoc, in the palace of agriculture and foods. The statues of women in theatrical costumes by the front door came from the Indochina pavilion, while the ornamental iron gate at the entrance was part of the Palace of Women. In the years after the exposition, La Ruche served as the temporary studio and home of dozens of young artists and writers including Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Fernand Léger and the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. It was threatened with demolition in the 1960s but was saved by culture minister André Malraux. It is now a historical monument.[61]

-

Ceramic gateway of Sèvres Porcelain from the Palace of National Manufacturers, now on Square Félx-Desruelles

-

Hector Guimard's original Art Nouveau entrance of the Paris Métro at Porte Dauphine

-

A 2.87 metres (9 ft 5 in) copy of the Statue of Liberty by Bartholdi, exhibited in 1900, placed in the Luxembourg Gardens in 1905

-

La Ruche, an artist's colony composed of pieces of different exposition buildings

Criticism

editThe exposition had numerous critics from different points of view.

The Porte Monumentale

editResponse to the monumental gateway was mixed, with some critics comparing it to a pot-bellied stove.[62] It was described as "lacking in taste" and was considered by some critics to be the ugliest of all the exhibits.[9] La Parisienne, made by Moreau-Vauthier,[9] was referred to by some as "the triumph of prostitution" because of her flowing robe and modernized figure and was criticized by many visitors.[2]

The interior of the central dome had niches holding large sculptures. One was described as both a personification of electricity and as Salammbô, Gustave Flaubert's infamous Carthaginian femme fatale, who was a symbol of light.[63] La Porte Monumental is considered to be a structure of the Salammbô style and 'the most typically 1900 monument of the entire exhibition'.[9]

The controversial gateway became known as La Salamanda among the public because it resembled the stocky and intricately designed salamander-stoves of the time, only adding to its ridicule.[2]

In literature

editThe American memoirist and historian Henry Adams wrote about the exposition in The Education of Henry Adams, in a chapter titled "The Dynamo and the Virgin." Adams used the occasion to ruminate upon the implications of the Machine Age, expressing concern over what he perceived to be a clash between technology ("the dynamo," a reference to the new engines on display) and the tradition of art and spirituality ("the Virgin," in reference to displays of older artwork) in addressing human needs. The chapter is considered to be an early iteration of the conversations about technology and life that continued in the 20th and 21st centuries.[64]

Motion picture footage

editShort silent actuality films documenting the exposition by French director Georges Méliès and by Edison Manufacturing Company producer James H. White, have survived.

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ This includes six world expositions (in 1855, 1867, 1878, 1889, 1900 and 1937), two specialized expositions (in 1881 and 1925) and two colonial expositions (in 1907 and 1931).

- ^ Including President William McKinley of the United States, Queen Victoria and her son Prince Edward of the United Kingdom, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary, Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra of Russia, and Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia. The titles of the figures are given in the border below them.

References

edit- ^ Ageorges, Sylvain, Sur les traces des Exposition universelles (2006) pp. 12-15

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Allwood, John (1977), The Great Exhibitions, Great Britain: Cassell & Collier Macmillan Publishers, pp. 7–107.[page range too broad]

- ^ Mabire, Jean Christophe (2000), p. 31.

- ^ a b Ageorges (2006), pp. 104-105.

- ^ a b c Exposition universelle internationale de 1900 à Paris. Rapport général administratif et technique (Report) (in French). Vol. 8. Paris: Ministry of Commerce, Industry, Posts and Telegraphs. French Republic. 1902. p. 640. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Silverman, Debora (1989). Art nouveau in fin-de-siècle France : politics, psychology, and style. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06322-8. OCLC 17953895.

- ^ Dymond, Anne (2011). "Embodying the Nation: Art, Fashion, and Allegorical Women at the 1900 Exposition Universelle". RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 36 (2): 1–14. doi:10.7202/1066739ar. ISSN 0315-9906. JSTOR 42630841.

- ^ Ageorges, Sylvan. Sur les traces des Expositions Universelles (2004), p. 238.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Jullian, Philipe (1974), The Triumph of Art Nouveau: Paris Exhibition 1900, New York, New York: Larousse & Co, pp. 38–83.

- ^ Dymond, Anne (2011). "Embodying the Nation: Art, Fashion, and Allegorical Women at the 1900 Exposition Universelle". RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 36 (2): 1–14. doi:10.7202/1066739ar. ISSN 0315-9906. JSTOR 42630841.

- ^ Ageorges (2006), p. 118.

- ^ a b Brown, Robert W (2008). "Paris 1900". Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions. McFarland & Company. p. 150.

- ^ Mabire (2000), p. 89.

- ^ a b Mabire (2000), p. 116.

- ^ Ageorges (2006), p. 110.

- ^ Ageorges (2006), pp. 113–114.

- ^ Exposition Universelle de 1900 - Catalogue illustré officiel de l'exposition décennale des BEAUX-ARTS de 1889 à 1900 (in French). Ludovic Baschet, éditeur. 1900.

- ^ Exposition Universelle de 1900 - Catalogue illustré officiel de l'exposition centennale de l'Art français de 1800 à 1889 (in French). Ludovic Baschet, éditeur. 1900.

- ^ Exposition Universelle de 1900 - Catalogue illustré officiel de l'exposition rétrospective de l'art français des origines à 1800 (in French). Ludovic Baschet, éditeur. 1900.

- ^ Ageorges (2006), p. 127.

- ^ Ageorges (2006), p. 123.

- ^ David Levering Lewis, "A Small Nation of People: W.E.B. Du Bois and Black Americans at the Turn of the Twentieth Century", A Small Nation of People: W. E. B. Du Bois and African American Portraits of Progress. New York: Amistad, 2003. 24–49.

- ^ Thomas Calloway, "The Negro Exhibit", in U.S. Commission to the Paris Exposition, Report of the Commissioner-General for the United States to the International Universal Exposition, Paris, 1900, Vol. 2 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1901).

- ^ Hulse, Lynn (2024-07-11), "Whichelo, Mary Eleanor [Nellie] (1862–1959), head designer of the Royal School of Art Needlework", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.90000382475, ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8, retrieved 2024-07-30

- ^ Lasheras Peña, Ana Belén (2 March 2010). España en París. La imagen nacional en las Exposiciones Universales, 1855-1900 (Thesis) (in Spanish). University of Cantabria. pp. 449–474.

- ^ Src='https://Secure.gravatar.com/Avatar/C9e8c4f79e6a7ed9d23957380b5c3606?s=20, <img Data-Lazy-Fallback="1" Alt=; #038;d=identicon; Srcset='https://Secure.gravatar.com/Avatar/C9e8c4f79e6a7ed9d23957380b5c3606?s=40, #038;r=g'; #038;d=identicon; Garcevic, #038;r=g 2x' class='avatar avatar-20 photo' height='20' width='20' loading='lazy' decoding='async' />Srdjan (2022-03-31). "Serbia and Yugoslavia at the World Fairs (1): 1885-1939". The Nutshell Times. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "EXPO Serbia | Istorijat Srbija". exposerbia.rs. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ a b c d e Mabire (2000), pp. 62–63.

- ^ Ageorges (2006), pp. 116–117.

- ^ Gers, Paul. "Paris 1900 - Korea - Foreign Nations and Colonies". worldfairs.info.

- ^ "Les points sur les i - Madame Choi". 28 July 2006.

- ^ Vogel, Robert M. (1961). "Elevator Systems of the Eiffel Tower, 1889". United States National Museum Bulletin. 228. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution: 20–21.

- ^ Mabire (2000), p. 86.

- ^ Mabire (2000), pp. 87–89.

- ^ Blaizot, Denis (26 May 1900). "Les trottoirs roulants de l'Exposition". La Revue Scientifique (in French).

- ^ Martin, Henry (1902). Lignes Aeriennes et Trolleys pour Automobile sur Route (Report) (in French). Libraire Polytechnique Ch. p. 29.

- ^ a b Ageorges (2006), pp. 110–111.

- ^ Ageorges (2006), p. 112.

- ^ Benjamin, Roger (2005). "Andalusia In The Time Of The Moors: Regret and Colonial Presence in Paris, 1900". Edges of Empire: Orientalism and Visual Culture. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 181–205.

- ^ a b c Mabire (2000), p. 177.

- ^ Dymond, Anne (2011). "Embodying the Nation: Art, Fashion, and Allegorical Women at the 1900 Exposition Universelle". RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 36 (2): 1–14. doi:10.7202/1066739ar. ISSN 0315-9906. JSTOR 42630841.

- ^ Rousselet, Louis. "Paris 1900 - World Tour Panorama". worldfairs.info.

- ^ Mabire (2000), pp. 80–81.

- ^ Skinner 1967, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Tierchant 2009, pp. 287–288.

- ^ Mallon, Bill (2009). The 1900 Olympic Games: Results for All Competitors in All Events, with Commentary. McFarland & Company. p. 11. ISBN 9780786440641. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "The Olympic Summer Games Factsheet" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ Journal of Olympic History, Special Issue – December 2008, The Official Publication of the International Society of Olympic Historians, p. 77, by Karl Lennartz, Tony Bijkerk and Volker Kluge

- ^ "1900 Paris Medal Tally". Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Mabire (2000), p. 46.

- ^ Mabire (1900), p. 44.

- ^ Ageorges (2006), p. 105.

- ^ a b Mabire (2000), pp. 51

- ^ a b Gontar, Cybele. (2006), "Art Nouveau", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved from: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/artn/hd_artn.htm

- ^ a b "ArtfixDaily.com ArtGuild Members". www.artfixdaily.com. Archived from the original on 2019-01-07. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ Sato 2015, p. 64.

- ^ a b Philippe Jullian, The Triumph of Art Nouveau: Paris exhibition, 1900 (London: Phaidon, 1974).

- ^ Ageorges (2006) p. 130

- ^ Paul Smith, Ministry of Culture and Communication, "Le patrimoine ferroviaire protégé" Archived 2018-04-15 at the Wayback Machine, 1999, rev. 2011, p. 3, at Association pour l'histoire des chemins de fer (in French).

- ^ "History of The Museums of the Far East". Museums of the Far East. Archived from the original on 2021-01-27. Retrieved 2021-11-30.

- ^ Ageorges (2006), pp. 124–125.

- ^ L'Aurore, 14 May 1901 and 23 April 1901

- ^ Dymond, Anne (2011). "Embodying the Nation: Art, Fashion, and Allegorical Women at the 1900 Exposition Universelle". RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 36 (2): 1–14. doi:10.7202/1066739ar. ISSN 0315-9906. JSTOR 42630841.

- ^ "The 1900 World's Fair Produced Dazzling Dynamos, Great Art, and Our Current Conversation About Technology". 30 August 2016.

Bibliography

edit- Ageorges, Sylvain (2006), Sur les traces des Expositions Universelles (in French), Parigramme. ISBN 978-28409-6444-5

- Dymond, Anne (2011), "Embodying the Nation: Art, Fashion and Allegorical Women at the 1900 Exposition Universelle," RACAR, v. 36, no. 2, 1–14. [1]

- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele (2015). L'Art Nouveau (in French). H.F. Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8480-0857-5.

- Lahor, Jean (2007) [1901]. L'Art nouveau (in French). Baseline Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85995-667-0.

- Mabire, Jean-Christophe, L'Exposition Universelle de 1900 (in French) (2019), L.Harmattan. ISBN 27384-9309-2

- Sato, Tamako (2015). Alphonse Mucha - the Artist as Visionary. Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-5009-3.

- Skinner, Cornelia Otis (1967). Madame Sarah. New York: Houghton-Mifflin. OCLC 912389162.

- Tierchant, Hélène (2009). Sarah Bernhardt: Madame "quand même". Paris: Éditions Télémaque. ISBN 978-2-7533-0092-7. OCLC 2753300925.

Further reading

edit- Alexander C. T. Geppert: Fleeting Cities. Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe, Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Richard D. Mandell, Paris 1900: The great world's fair (1967)

- Le Panorama : Exposition universelle 1900 (in French). Paris: Ludovic Baschet, éditeur. 1900. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- Liste des récompenses : Exposition universelle de 1900, à Paris (Report) (in French). Paris: Ministry of Commerce, Industry, Posts and Telegraphs. French Republic. 1901. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

External links

edit- 1900 Paris at the BIE

- Exposition Universelle 1900 in Paris. Photographs at L'Art Nouveau

- Universal and International Exhibition of Paris 1900 at worldfairs.info

- Inventing Entertainment: The Early Motion Pictures and Sound Recordings of the Edison Companies: "exposition universelle internationale de 1900 paris, france" (search results). A set of films by Edison from the Expo 1900

- 1900 Palace of Electricity. Thomas A. Edison. Archived from the original on 2021-11-17. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

1900-08-09

1 minute film pan shot from Champ de Mars - 1900 Panoramic view of the Place de l'Concord. Thomas A. Edison. Archived from the original on 2021-11-17. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

1900-08-29

1 minute 39 seconds film pan shot from Place de la Concorde - 1900 Esplanade des Invalides. Thomas A. Edison. Archived from the original on 2021-11-17. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

1900-08-09

2 minute film pan shot from Esplanade des Invalides and 10 seconds of Chateau d'Eau from Tour Eiffel - "Unrecognizable Paris: The Monuments that Vanished", an article at Messy Nessy Cabinet of Chic Curiosities

- The Burton Holmes lectures; v.2. Round about Paris. Paris exposition at Internet Archive