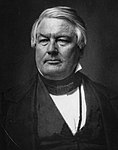

The 1844 New York gubernatorial election was held on November 5, 1844. Incumbent Governor William C. Bouck lost his bid for nomination to U.S. Senator Silas Wright. In the general election, Wright defeated former U.S. Representative and future President of the United States Millard Fillmore.

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Results by county Wright: 40-50% 50-60% 60-70% Fillmore: 40-50% 50-60% | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Both Wright and Fillmore had been candidates for the vice presidency earlier in the year, but Wright declined the nomination by the Democratic National Convention, while Fillmore's active efforts were blocked by party boss Thurlow Weed.

Democratic nomination

editBackground

editGovernor William C. Bouck was elected in 1842 over Whig Luther Bradish. His term was occupied primarily with the state's response to the Anti-Rent War.[1] Tenants who held perpetual leases under the patroon system, first implemented when New York was a Dutch colony, objected to the "quarter sale" provision of their leases.[2] Under this provision if a tenant sold his lease, he had to pay his patroon one quarter of the sale price or one additional year's rent.[2] In addition, while the wealthiest patroon, Stephen Van Rensselaer, had generally proved a benevolent landlord usually willing to accept partial or late payments rather than evict tenants who fell behind on their rent, after his death in 1839 his heirs attempted to collect long-overdue payments.[3] When the tenants could not pay and could not negotiate for favorable repayment terms, they were threatened with eviction and a revolt ensued.[3]

Bouck was sympathetic to the tenants,[4] but as part of the effort to restore order during a violent demonstration, near the end of his term he sent units of the state militia to Hudson, which was viewed unfavorably by the tenants and their supporters.[5] Bouck's popularity within his own party also slipped, as Democrats sought a candidate who would consistently enforce the law against rioters.[5]

The 1844 election was also cast in the shadow of the election for president. Senator Silas Wright, a critic of the annexation of Texas and slavery, supported his ally Martin Van Buren for the presidency.[6] When the 1844 Democratic National Convention deadlocked and James K. Polk of Tennessee was nominated, southerners sought to appease the Van Buren wing of the party by nominating Wright for Vice President, but he firmly declined.[7]

Whig nomination

editBackground

editIn contrast to Wright, former U.S. representative Millard Fillmore, who had chaired the influential House Ways and Means Committee during his time in Congress, actively sought the vice presidency on the Whig ticket.[8][9] However, he was blocked by party boss Thurlow Weed, who preferred the spot for former governor William H. Seward. Although Weed promised Fillmore the governorship, Fillmore wrote back, "I am not willing to be treacherously killed by this pretended kindness ... do not suppose for a minute that I think they desire my nomination for governor."[10] Although Weed failed to secure the nomination for Seward, he succeeded in blocking Fillmore; Theodore Frelinghuysen of New Jersey was the eventual nominee.[11]

Putting a good face on his defeat, Fillmore met and publicly appeared with Frelinghuysen and quietly spurned Weed's offer to get him nominated as governor at the state convention. Fillmore's position in opposing slavery only at the state level made him acceptable as a statewide Whig candidate, and Weed saw to it the pressure on Fillmore increased. Fillmore had stated that a convention had the right to draft anyone for political service, and Weed got the convention to choose Fillmore, who had broad support, despite his reluctance.[12]

General election

editCandidates

edit- Millard Fillmore, former U.S. Representative from Buffalo

- Alvan Stewart, nominee for governor in 1842 (Liberty)

- Silas Wright, United States Senator (Democratic)

Campaign

editAlthough Fillmore worked to gain support among German-Americans, a major constituency, he was hurt among immigrants by the fact that in New York City, Whigs had supported a nativist candidate in the mayoral election earlier in 1844, and Fillmore and his party were tarred with that brush.[13]

Results

edit| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Silas Wright | 241,090 | 49.48% | 2.35 | |

| Whig | Millard Fillmore | 231,057 | 47.42% | 1.06 | |

| Liberty | Alvan Stewart | 15,136 | 3.12% | 1.31 | |

| Total votes | 487,283 | 100.00% | |||

References

edit- ^ Mayham 1906.

- ^ a b Torrance 1939.

- ^ a b Persico 1974.

- ^ Summerhill 2005, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Dearstyne 2015.

- ^ Hammond 1848, pp. 456=457.

- ^ Jenkins 1851, p. 779.

- ^ Scarry 2001, pp. 1776–1820.

- ^ Rayback 1959, pp. 2417.

- ^ Rayback 1959, pp. 2425–2471.

- ^ Rayback 1959, pp. 2471–2486.

- ^ Rayback 1959, pp. 2486–2536.

- ^ Rayback 1959, pp. 2536–2562.

- ^ Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York. 1852. p. 367.

Bibliography

edit- Dearstyne, Bruce W. (2015). The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State's History. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4384-5659-1 – via Google Books.

- Hammond, Jabez D. (1848). Life and Times of Silas Wright, Late Governor of the State of New York. Syracuse, NY: Hall and Dickson.

- Jenkins, John S. (1846). History of Political Parties in the State of New-York. Alden & Markham. p. 466.

- Jenkins, John S. (1851). Lives of the governors of the state of New York. Auburn, NY: Derby and Miller. p. 724.

- Mayham, Albert Champlin (1906). The Anti-Rent War on Blenheim Hill. Jefferson, NY: Frederick L. Frazee. pp. 39-40 – via Internet Archive.

- Persico, Joseph E. (October 1974). "Feudal Lords On Yankee Soil". American Heritage. Vol. 25, no. 6. Rockville, MD: American Heritage Publishing Company.

- Rayback, Robert J. (1959). Millard Fillmore: Biography of a President (Kindle ed.). Pickle Partners Publishing.

- Scarry, Robert J. (2001). Millard Fillmore (Kindle ed.). McFarland & Co., Inc. ISBN 978-1-4766-1398-7.

- Summerhill, Thomas (2005). Harvest of Dissent: Agrarianism in Nineteenth-century New York. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-2520-2976-9 – via Google Books.

- Torrance, Mary Fisher (1939). The Story of Old Rensselaerville. New York, NY: Privately Printed. p. 16 – via Internet Archive.